Jack Malotte’s artwork has captured the beauty of the Great Basin region and spoken to the political and environmental issues that plague it.

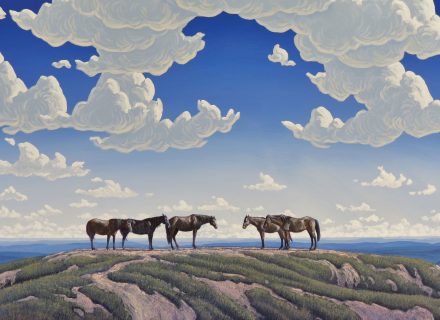

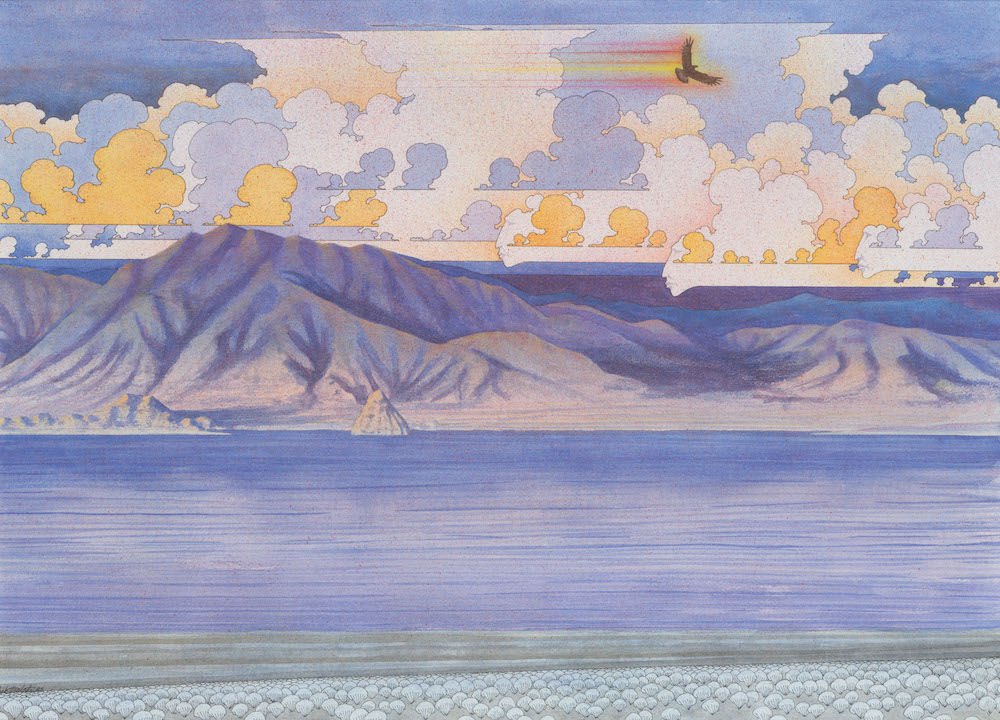

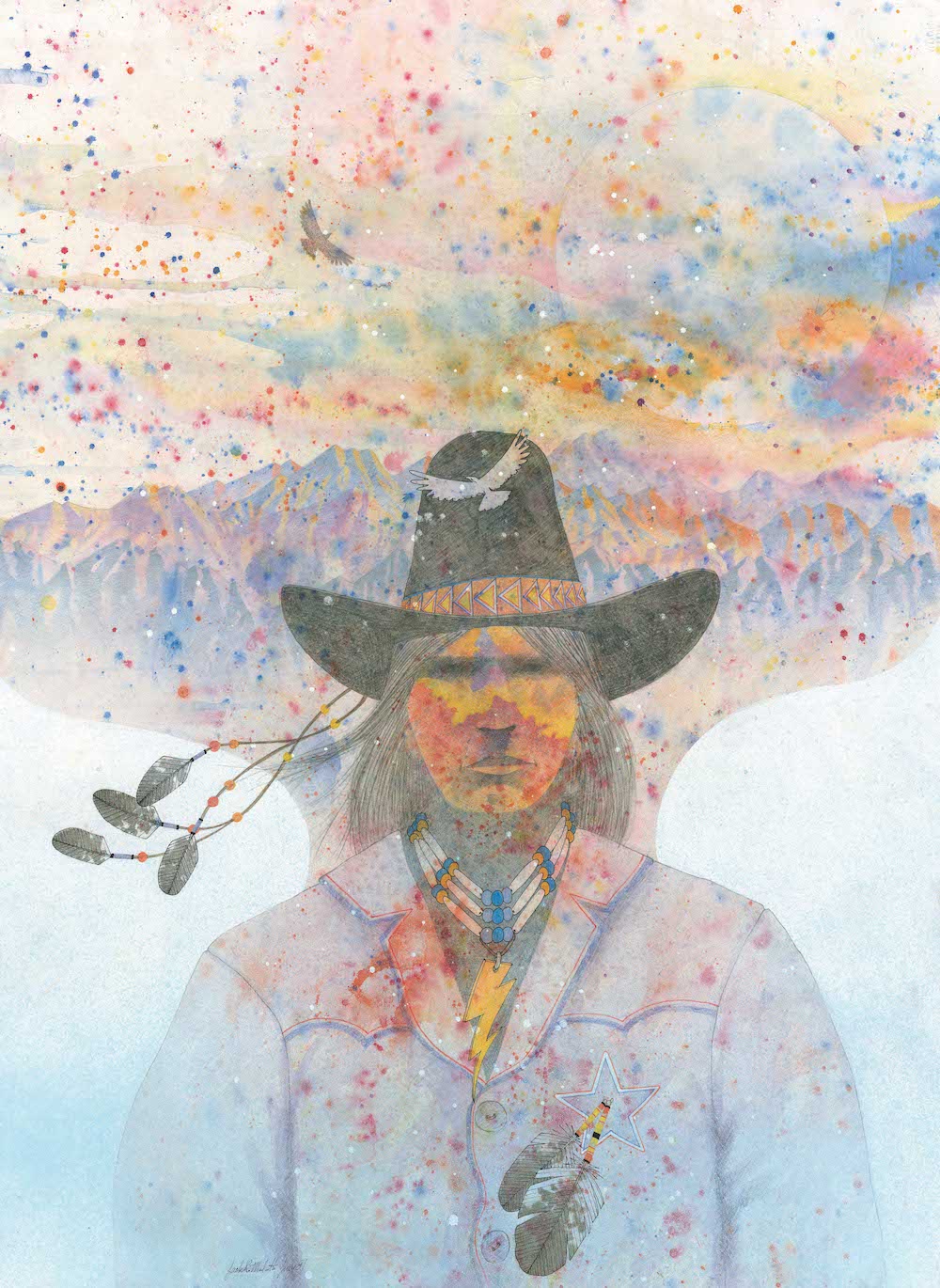

For 40 years, Jack Malotte’s artwork has captured the beauty of the Great Basin region and spoken to the political and environmental issues that plague it. A tranquil landscape; a stormy night sky; a stoic cigarette-smoking, sunglasses-clad Native American set against a mining backdrop with military jet and eagle overhead; a depiction of a nuclear future that would be strikingly beautiful if it weren’t for the horrific subject matter — the soft-spoken artist’s work speaks loudly.

Forever experimenting with new techniques, Malotte says he doesn’t like “to be boxed in.” He wants to be free to go in any direction he desires rather than be identified as a silk-screener, a painter, or an artist who does line drawing or landscapes.

“I like mixing the modern and the old, night and day — opposite sorts of things,” he says. “I like mixing those things up. And I like creating things that make invisible things visible, like wind. Sometimes I’ll do a spirit. A lot of my drawings are just how I feel at the moment, free-handed, freestyle.”

Early in his career, working closely with Western Shoshone activists and environmental groups, he focused on Indian grazing rights, mining and water rights, nuclear issues, and other politically charged subjects. In more recent years, his activism has mellowed, although the military jet frequently still appears in his art — an indication of the U.S. military’s presence not only on hundreds of thousands of acres of Nevada’s lands but also in its airspace. And Malotte likes to promote — or provoke — dialogue with a variety of humorous logos such as Indian Uprising Designs, Colonized Mind Designs, Pesky Redskins Designs, and Wretched Savages Designs. “I put in little political jabs by putting in little logos,” he says.

Born in 1953 in Schurz, Nevada, and raised on the Reno-Sparks Indian Reservation, Malotte is Western Shoshone and Washoe. He studied at the California School of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts) but returned to Nevada, where he now lives and works in the tiny town of Duckwater (population: 192) in the heart of the Great Basin at the edge of the Duckwater Indian Reservation. “When I moved out here, people thought I died,” Malotte says, laughing. That was 20 years ago. In the years since, he has accumulated lots of artwork and books, which fill his trailer studio. “Nobody comes out here to look at artwork,” he says. “That’s why I have so much. I just put it away. I don’t know what’s good and what’s bad. I just do it, hoping it’s OK.”

The Nevada Museum of Art has no such doubts and has mounted the retrospective The Art of Jack Malotte. “It’s rare to find an artist with the foresight to hold onto materials from all different times of his life,” says Ann Wolfe, the museum’s curator. “It can be a bit overwhelming for an artist, when a curator comes and wants to look through every single piece and pieces that he thought might just be scraps or things that don’t hold as much value to him.”

In addition to the roughly 200 pieces showcased in the exhibition, an exterior wall of the museum features a mural by Malotte and several colleagues. At one end, lightning represents the power of nature; the middle section features a landscape reminiscent of Duckwater; on the far left, eagle feathers, symbolizing spirituality, appear to be falling down. “A moon brings the whole thing together and reminds us that we’re just little things out here floating in space,” Malotte says. “I feel humble. I like the thought that we’re just way out here in the middle of blackness floating around, fighting about every little thing.”

The Art of Jack Malotte is on view at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, Nevada, through October 20. A companion book is available. nevadaart.org, facebook.com/jack.malotte

Photography: (featured): Untitled [figure in profile], 1995, private collection; Untitled [blue lake with yellow clouds panorama], 1985, private collection; The Cowboy Guy, 1981, courtesy of the artist. All images courtesy Nevada Museum Of Art.

From the October 2019 issue.