Colter Wall’s Little Songs feel lived-in because he lives them. He values his Saskatchewan ranch as much as his celebrated cowboy music.

It’s an early summer afternoon in the southwest corner of Saskatchewan. Singer-songwriter Colter Wall sits on the bed of his F-350 in the middle of the Canadian prairie at his ranch, the Rafter CW, where he runs a yearling cattle operation. There is a daunting pile of scrap posts next to him (“I inherited them with the place,” he says with a chuckle), several drought-resistant Caragana trees edging the property, and a nice set of steel corrals with a loading chute set in the back.

Wall’s ranch sits on the northern end of the Great Plains. Covering over a million square miles, the Plains are a massive swath of land roughly encompassing the Llano Estacado in northwestern Texas to the bottom of the prairie provinces of Canada and running west of the 100th Meridian to the eastern edge of the Rockies. In modern times it's a place that’s often overlooked, mistakenly seen as a conglomeration of flyover states and provinces—but it shouldn’t be. It’s a landscape with a dramatic story, from the Western lore of emigrant and cattle trails of the 19th century to its ecological significance as one of the most endangered ecosystems in the world.

For Wall, it’s home. “I'm predisposed to the openness and the emptiness of the prairie,” he says.

“If you grow up in this kind of country, I think you either come to hate it—you think it’s boring, there’s nothing out here, just this big open country that goes on forever, not even a tree to look at. Or, if you’re like me, you find comfort in it.”

Wall’s sense of place and deep appreciation for the prairie is so ingrained in him that his recent album, Little Songs (via La Honda/RCA Records), pays homage to it. Where Wall’s previous works have celebrated cowboy culture, Little Songs retains that reverence but now with an equal dose of reality. A reality that is difficult to incorporate without experiencing firsthand, something Wall is distinctly aware of. “This is everyday life for those farming and ranching. I like to think of myself as one of them, of course, but what I do [in comparison] is pretty small and insignificant. But I live with these people, and we work together. These people are my neighbors.”

Press play to hear the entire album on Youtube.

In Little Songs, Wall explores drought, wind, depression, the financial burdens of running a ranching operation, and isolation, with lyrics that resonate on a visceral level. When in the title track, “Little Songs,” he sings about a woman “fighting drought and her own mind/Day by day, she’s been losing/To the wind,” I go back to a memory on the high desert in the San Luis Valley of Colorado. I was moving cattle on horseback, pulling my hat down to my brow in desperation as a windstorm pelted grains of sand violently at my face. Riding next to me, my friend had a defeated look in his eyes as he cussed at the weather. By the end of the week, he had withdrawn completely; the extreme wind had kicked his anxiety into high gear.

As I recount the story to Wall, he is empathetic. “The prairie can be maddening. There’s an area west of here in the hills called Maryflat. The story goes that the early settlers lost their minds in it. It’s really tough country.” In addition to the accurate vignettes of agrarian lifestyle, the title track features Roy Nichols-esque guitar picking and intimate “sitting right next to you” dry vocals. This song, production-wise, leans closer to barroom country than campfire western—and lyrically, half a nod to Canadian singer Ian Tyson and a half to rural women of the West. “Ian’s influence crept into this song and the entire album. I wrote this when he was alive, and then he went ahead and died. It’s kind of an almost spooky thing.” Wall’s right: the line “there’s an old man in the foothills/if he ain’t dead, he’s living there still” now has prophetic energy.

Wall further pays tribute to Tyson with his rendition of “The Coyote & The Cowboy,” a cheeky recording with one sly lyric edit, a swap of “old long noose saloon” to “old jasper saloon”—his local watering hole. Why artists choose specific songs to cover is telling, and it’s difficult not to appreciate Wall’s choice here: an admiration for one of the West’s most misunderstood (and often detested) animals, the coyote.

“The Coyote & The Cowboy” and “Evangelina” are the two covers on the album. Both are thoughtful musical interpretations of Wall’s predecessors and a fine example of his historical reverence and legwork. However, the stand-outs on this album are his originals.

“Corralling the Blues” is a rare moment of vulnerability. With sparse melancholy instrumentation and patient phrasing, the emotive tune is arguably one of the most significant songs in Wall’s catalog. With lyrics like, “It’s a feeling I have known/Since before I was grown/I’m howling, corralling the blues,” Wall speaks plainly about mental health.

“[Corralling the Blues] is such a personal song that initially, I was mostly writing about myself. But as it took shape, it became evident it was more of a universal feeling, especially for people in agriculture.” Ranching and farming professions are disproportionately affected by suicide, with rates estimated as high as three times the general population.

“I’ve seen those numbers too, and they’re hard to ignore,” says Wall compassionately, “but I’ve also seen it in the community—and how it can take hold of people, especially in the wintertime. The sky gets gray, and the country can look pretty monochromatic. There’s snow everywhere, and going outside feels like getting the shit kicked out of you because the wind howls, and it's 40 below. That’s enough to wear down anybody, not just physically but emotionally and mentally too.”

It’s encouraging to have artists like Wall engaging in these conversations and understanding their importance. Fortunately, organizations like Young Farmers Coalition and Willie Nelson’s Farm Aid provide extensive services for ranch and farm workers, including access to mental health resources. “I think there’s an attitude of independence in these communities, and you’re your own boss. It’s a necessity to be self-reliant. You know, tough it out, figure it out, do it yourself, take care of it yourself. Which is often a good attitude until a person [needs support with] mental health. It’s a reality and a human problem, regardless of where you’re from and what you do. I wasn’t thinking about it from that broad of a spectrum when I wrote that song, but when it was done, I realized it wasn’t just for me.”

While Little Songs has its pensive moments, it has celebratory ones too. The types of songs that elicit an instant kinetic response from the listener, be it a shy tap of the foot or a proud turn in the dancehall. “Honky Tonk Nighthawk” is one of those nostalgic country songs that places the listener squarely on a barstool at a dancehall like the Broken Spoke in Austin. You can see the neon lights glowing through a hazy window, smell the sawdust on the floor, laugh at the posters of George Strait covered in lipstick, and admire the older couple wearing well-earned trophy buckles and fine felt Stetsons–moving together with decades of familiarity.

“There are so many great dance halls and old bars in Texas, and I took full advantage of that. I did some drinking and dancing in those cool places and wrote this song one of the mornings after.”

From the barroom to the branding pen, Wall’s music encompasses many iterations of Western traditions. “Honky Tonk Nighthawk” was explicitly written as a dance tune and borrowed heavily from string band traditions. “Musically, that song ended up being a nod to Western swing and Texas music, specifically Bob Wills. The opening lick is the old ‘Milk Cow Blues’ fiddle lick. The song plays tribute to the old Western swing, which is a nice way of saying ripping it off,” Wall says with a laugh.

Wall has a history with Texas, from cowboying at his friends' ranches to selling out famed dancehalls like Billy Bob’s in Fort Worth. He chose the Lone Star State to record Little Songs at Yellow Dog Studios in Wimberly, which he was partial to because of the scenic hill country, proximity to the Pecos River, and bunkhouse-style accommodations.

Where most artists hire session players for in-studio work, Wall used his current or former band members (most notably, Patrick Lyons, a longtime collaborator of Wall’s who co-produced the album and plays a myriad of instruments).

“When I had a copy of the vinyl, I laughed when I looked at the liner notes. Under my name, it says vocals and guitar, but under Pat’s name is an entire paragraph. The guy plays every instrument.” Twelve on this record, to be exact. Wall did not go into the studio with the intention of Lyons co-producing, but he quickly became invaluable through his extensive musical knowledge, talent as a player, and ability to guide the record sonically. “He’s so well-versed in the recording world. I’m pretty grateful to have him working for me in many different capacities on this record.”

The rest of the players on the album include Jake Groves on harmonica, Jason Simpson on bass, Russell Patterson on drums, and Doug Moreland on fiddle. Groves gives a dazzling minute-long harp outro on the record’s ending song, “The Last Loving Words,” a clever and tender track that memorializes the fated friendship of ranchers Oliver Loving and Charles Goodnight. Loving was killed by a Comanche arrow on a cattle drive in New Mexico, and Goodnight promised to bury him in his home state of Texas. The story inspired Larry McMurtry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning western Lonesome Dove—Wall’s favorite book.

Wall is creating his own Western legacy as one of the most prominent figures in the country & western revival, a genre that hasn't seen real mainstream success since the Marty Robbins gunslinger hits of the 1950s and 1960s and Bob Wills-inspired Merle Haggard cuts of the 1970s. Most of us threw away “western” and kept “country” long ago, but Wall puts the two back together. Instead of opting for genres with more commercial security, Wall is steadfast in pursuing what resonates with him. This guides not only his musical preferences but his lifestyle too. He opts to live in rural Saskatchewan instead of a music-centric city like Nashville. His calendar is dictated by his ranching operation instead of a tour schedule, and he rarely engages with the media. Instead of hindering his popularity, it has added to his mystique.

In “Standing Here,” a self-narration track with a dancing two-step beat, the typically restrained Wall gives a rare peek into why he navigates the world as he does. A straightforward and literal song, Wall wrote it during a drought while looking out a window, sharing some of his ruminations. Many of his frustrations are relatable–frustrations about the weather and politics. However, one perspective unique to Wall’s occupation is the dynamics of the music industry.

As Wall boldly proclaims, “I’m just hiding out/From all them music people/I’m sure they’d all claim to be my friends/But I’m not lying now, They’d sell me for a nickel/In my future or my pasture, they ain’t welcome in.” I sheepishly asked Wall about the lyrics (nervous I was one of the dreaded “music people”), and his answer was insightful.

“I don’t want to sound like an old curmudgeon, because there are great people who work in the music industry, and I’m lucky to work with some of them. But, I think that it’s important to have some distance. There's such a weird thing that happens in places like Nashville or Austin, where everyone you know is more or less involved in the entertainment industry.

"I think a lot of times, and it probably happens unintentionally to a lot of people here, people get distracted by the business side, or even the scene, or clique. I just recognized early on, it wasn’t something that appealed to me. When I wrote that verse, it wasn’t because I wanted to call anybody out. I also had to get to the point where I could take a step back from it, and I understand it can be necessary. But the music scene isn’t my whole world, and I never want it to be, because to me that can be limiting. It’s limiting as a human being and also as a songwriter.”

Wall’s conviction to do what resonated with him instead of what was expected is one of the defining elements of his sound. His pivot from Nashville back home to rural Southern Saskatchewan has also given a voice to a biome deeply needing attention, the native prairies. Temperate grasslands have decreased at an alarming rate, with less than half of the original ranges left globally and less than 30 percent in North America. The shortgrass prairie of Wall’s home is estimated at only 17-21 percent of its original range. This dynamic ecosystem is the habitat to many fascinating species, including Plains bison, pronghorn, swift fox, and numerous grasslands birds.

Culturally, this area has a rich ranching heritage, and responsible grazing practices provide a compelling tool to support native grasses. When cattle are strategically used, they can mimic large keystone herbivores, like bison, to provide grazing and disturbance on the prairie. Grasslands National Park located in Val Marie, Saskatchewan, currently utilizes cattle and bison in their grazing program and has had improvements in the quality of grasses since the 1980s.

While Wall implements some of these strategies on his own property where he is able, like rotational grazing and the use of native grasses, his biggest contribution (intentional or not) is connecting people to these landscapes.

Little Songs is infused with his love for the plains. From the opening track, “Prairie Evening/Sagebrush Waltz,” Wall’s tender sweetheart song–his lyrics are steeped with references to the land like “old native prairies” and “sage on the soles of our shoes.” Like a true relationship, his observations aren’t all romantic. In “Standing Here” and “Little Songs,” he refers to the drought, the wind, and waiting for rain. His admiration for his home includes all iterations of it, the good and the bad.

Where his first EP, Imaginary Appalachia, was portraying a supposed life, in Little Songs, Wall is sharing his lived reality. This intimacy is squarely placing him among the literary and songwriter greats of the North American West, and more specifically, those with a deep appreciation of the plains like Willa Cather, Larry McMurtry, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Ian Frazier, and Wallace Stegner. His catalog is being utilized in many modern television westerns, including Deadwood and Yellowstone.

“With these songs, I’m writing about it because I have experienced it. I’m in the thick of it, and I’m glad to be. With all the troubles and things that come with it.”

Wall heads off to check for algae in his heifers stock tanks, to get back to his life on the prairie. To fill the big empty with little songs.

Listen to Colter Wall’s music and keep tabs on appearances at colterwall.com.

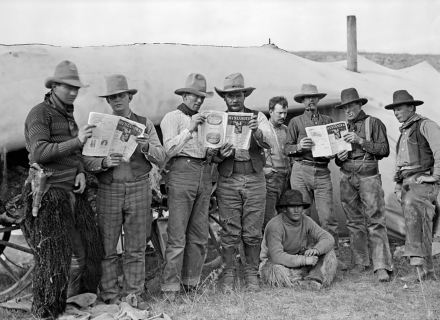

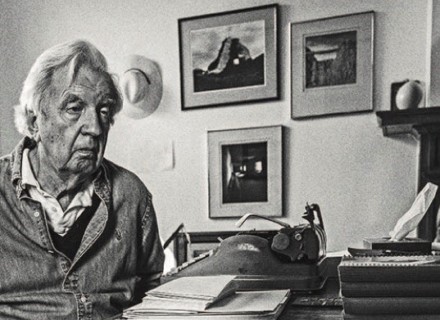

(Photography: Courtesy Little Jack Films)