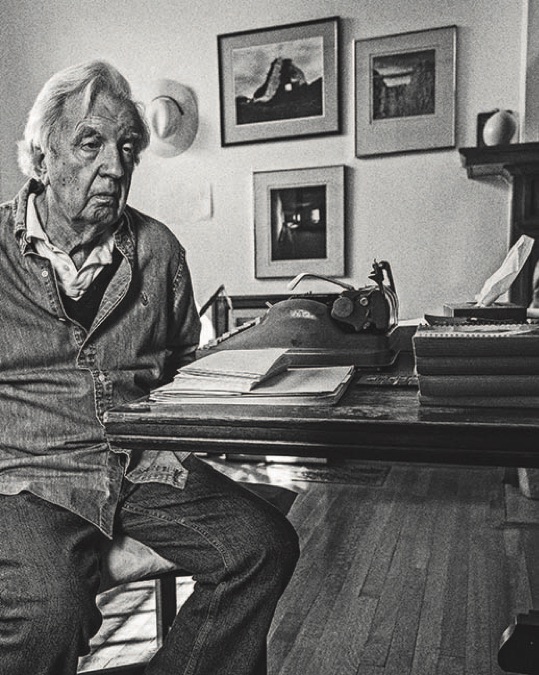

The Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Lonesome Dove turns 35 this year and its author 84, but Larry McMurtry isn’t looking back or standing still for praise.

Larry McMurtry isn’t an easy man to argue with. Not only is he one of the most well-read people you’ll ever meet, he’s more than happy to unload a terse opinion or three. And he doesn’t suffer fools gladly.

This doesn’t stop me from trying to convince the legendary Texas author of a simple fact most of the world accepts as obvious — that his 1985 epic Lonesome Dove is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, western novels ever published. I’ve got facts in my corner. These include numerous page citations highlighting brilliant literary passages, bank-busting sales figures, and the Pulitzer Prize the book was awarded in 1986.

McMurtry weighs the evidence. But he isn’t convinced.

“I just sat down and wrote it. I think the Berrybenders series is better, and a masterpiece,” he says, referring to his own collection of four novels about a calamitous 1830s hunting expedition published between 2002 and 2004. “Lonesome Dove was a good try.”

No matter how much I try, it just isn’t possible to get McMurtry to acknowledge that the book that introduced the world to retired Texas Rangers Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call — inspired by the lives of Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving and the West’s most famous cattle drive to Montana — amounts to much more than a pleasant way to pass some time.

“I hope readers enjoy the book,” he says, bordering on indifference.

“I wrote Lonesome Dove in the main to try and understand my father, who was as fine a cowboy as I’ve ever known.”

Like many great artists, McMurtry is uncomfortable discussing his own work. “I’m not good at defining things,” the famously media-shy Bob Dylan once told the Los Angeles Times. “Even if I could tell you what [a] song was about I wouldn’t. It’s up to the listener to figure out what it means to him.”

McMurtry is cast from the same mold as Dylan. Or maybe as the famously prickly Captain Call, who also didn’t much care for a fuss. As McMurtry tells me when I try to get him to open up about his most famous work: “I don’t enjoy interviews.”

Regarding Larry McMurtry that much at least is indisputable.

This year marks the 35th anniversary of the publication of Lonesome Dove, which McMurtry actually began more than a decade earlier as a screenplay written with Peter Bogdanovich. Called Streets of Laredo, the eventual movie was meant to cast John Wayne as Call, Jimmy Stewart as Gus, and Henry Fonda as Jake, but when Wayne dropped out, the project was scuttled. It took 15 years and McMurtry’s random sighting of a bus painted with “Lonesome Dove Baptist Church” on the side to impel him to start the story over as a novel.

That novel would go on to sell more than 4 million copies.

The 800-plus-page epic, of course, is more than just a literary phenomenon. The 1989 TV miniseries starring Robert Duvall (as Gus) and Tommy Lee Jones (as Call) is surely one of the most watched westerns in history. An estimated 26 million homes tuned in when it was first broadcast. By McMurtry’s estimate, somewhere north of 150 to 200 million people have now seen it.

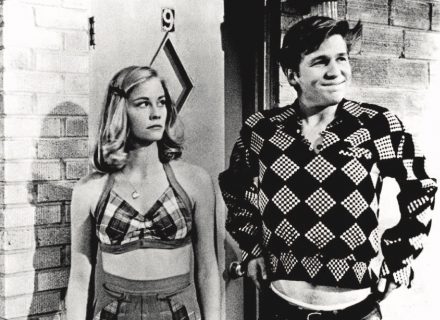

Though one of more than 30 books by McMurtry — he’s also written or co-written more than 40 screenplays including The Last Picture Show and Brokeback Mountain — Lonesome Dove is that rare critical and commercial success that places its author in the pantheon of American literary legends. There are books that suspend in amber a specific place and period in U.S. history: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Look Homeward, Angel by Thomas Wolfe, The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden by John Steinbeck, Lake Wobegon Days by Garrison Keillor. Rising above what he’s called western literature’s “vast desert of pulpers,” McMurtry and Lonesome Dove are part of that gilded group.

To mark the book’s anniversary, Simon & Schuster, McMurtry’s longtime publisher, will issue a new cover design for Lonesome Dove and its sequels. Various media will lionize the author. McMurtry will follow it all with bemused detachment. He’s often said he doesn’t consider Lonesome Dove a great book. It’s not even clear whether he’s watched the entire miniseries.

“I’m emotionally invested in my novels as I write them, but once they’re finished, that emotional investment drains away,” he says. “I don’t watch most of my adaptations. The Lonesome Dove miniseries is eight hours long, and I long ago exhausted my interest in it.”

That dispassionate distance may account for the blasé acceptance of the fact that he never completely cashed in on Lonesome Dove’s success. In his 2010 memoir, Hollywood, McMurtry writes that his agent, the illustrious Irving “Swifty” Lazar, botched the book’s theatrical royalty agreement to a particularly costly tune.

“The money stream that is Lonesome Dove is still flowing now,” he wrote. “I figure Irving Lazar cost me at least $15 million, a sum that would always be useful. But I loved him anyway and so did many others.”

So how much has McMurtry made from the miniseries?

“I believe the figure is somewhere shy of $300,000,” he says.

As the men in charge of the book’s Hat Creek Cattle Company, Gus and Call rightly get top billing. But Lonesome Dove’s secret weapon — the thing that assures the book will survive well into this century and the next — is the authenticity with which McMurtry paints its supporting cast. From young Native braves to Southern lawmen to Irish immigrants on the range, McMurtry imbues even bit characters with astonishing depth. Then he pulls off the mystic feat of all hallowed American writers: conveying their complexity with deceptively simple language.

A powerful example is the scene in which Gus and Call preside over the hangings of an outlaw gang, which tragically includes their friend and onetime Ranger companion Jake Spoon. McMurtry presents each man’s reaction to his own impending death — shock in one, resignation in another, fury in a third, a final flash of frontier dash in the case of Spoon — with such potent imagery it’s hard to imagine why anybody would ever need a movie to visualize it. Look online today and you’ll find commentators using “the hanging of Jake Spoon” as a political lesson for those on both the left and right sides of the country’s current political trench — testament to Lonesome Dove’s broad patriotic appeal.

“I rarely recall writing specific passages in any of my books,” says McMurtry when I ask whether he labored over that spleen-churning chapter. “As I’ve said in the past, when I begin a first draft, I sit down and write five pages a day. If I labor over any part of a novel, it’s the beginning. Once I have the beginning in acceptable form, I move on from there — again, writing five pages a day, no more, no less.”

The shadow cast by another unforgettable character, the arch-villain Blue Duck, is so powerful I was shocked to find, after re-reading the book for the first time in years, that he doesn’t make his first appearance until more than a third of the way through the novel.

“Belle Starr, a rather famous female outlaw, had a boyfriend named Blue Duck. The name derived from him,” McMurtry tells me. “I knew Blue Duck was a great villain. The force of evil, if you can harness it, is powerful.”

Even if living lives constricted by social mores of the time, the women of Lonesome Dove are no less interesting than the men and usually stronger. The young beauty Lorena knows the men who pursue her better than they know themselves. “It was clear to her already that he was one of those men somebody had to take care of,” Lorena intuits of one handsome rake who attempts to move in on her.

But it’s only Gus’ onetime love Clara — for whom he still carries a torch — who can spar with Gus and come out on top. When Gus brings Lorena (whom he’s rescued from the clutches of kidnappers) to stay at the now-married Clara’s house, she scolds him for bringing the young woman into her home.

“It happened accidentally, like I mentioned,” Gus tells her.

“I never noticed you having such accidents with ugly girls,” Clara shoots back.

The cattle drive to Montana provides the sweeping foundation of the story, but it’s that pitch-perfect period dialogue that brings the characters to life so vividly it can often feel to the reader like a kind of magic trick. I’m not the first to equate McMurtry’s skills with prestidigitation. “He knots and unknots stories as easily as can be,” wrote a New York Times reviewer in 2003.

McMurtry demurs. “I’m not conscious of it being a trick,” he says. “It’s just in a day’s work.”

McMurtry grew up in rural Texas, in and around Archer City, in the 1930s and ’40s. The dialogue in many of his books is based on the unique idioms and rhythms employed by his father, uncles, and other ranchers in the area.

“Nothing was more evident about my father than that he hated farming, he himself being a cattleman, pure and simple, amen,” he’s written.

Books were largely absent from the McMurtry home. Instead, he grew up surrounded by the voices of rural Texas, including that of his grandfather, who told stories about Texas pioneer life while sitting atop the roof of a storm cellar.

“The fact of the bookless ranch house meant that before the age of five or six I lived in an aural culture,” he wrote in his 2008 memoir, Books. “My mother, father, grandfather, grandmother, and whatever uncles or cowboys happened by, sat on the front porch every night in good weather and told stories.”

Is that where he picked up all the famously witty Lonesome Dove lingo? Who can forget the loquacious Gus talking to a stump if there was no nearby ear to bend, or using his favored euphemism for sexual intercourse (poke)?

“I read that somewhere, probably in the Dictionary of Slang,” McMurtry says. “The disappearance or twilight of lifestyles and professions are natural themes in my books. Showgirls, cowboys, dying breeds.”

Born into a family of storytellers, McMurtry wouldn’t have books of his own to feed his natural bent until a cousin left a box of 19 of them at the ranch on his way to enlisting in World War II. The first of the adventure tales he read from cover to cover was Robert Leighton’s 1929 Sergeant Silk, The Prairie Scout, the first words of which seem to foretell some of McMurtry’s most beloved subject matter: “ ‘If you ask me, there’s nothing like riding across the open prairie for quickening a fellow’s eyesight.’ ”

Over the last many years, McMurtry’s only become more devoted to books and the bibliophile life. He still lives in Archer City, a couple of hours northwest of DFW International Airport, where he’s surrounded himself with a personal library of some 25,000 books. He says amassing the collection is one of the principal achievements of his life. Of these volumes, the visitor might wonder, how many are westerns or about the West?

“Not many,” he says. “Very few, in fact.”

His library exists in addition to the 150,000 to 200,000 volumes on hand at any given time at Booked Up, the Archer City bookstore McMurtry has run for more than 50 years. A lifelong book collector, buyer, and trader, he founded the business in Washington, D.C., and ran it there for many years. It now occupies three buildings around Main Street. “Novelist, screenwriter, bookman” is how he prefers to be described. In that order.

Beyond his lifelong devotion to books, McMurtry is loath to give up personal details. When I ask about significant disappointments or heartbreaks in his life he replies, “No comment.”

“For an accurate estimation of my personality, one might look to my writing partner of the past 27 years, Diana Ossana, for her observations,” he says. “I believe that she has come to know me better than I know myself.”

Ossana is thankfully more candid.

“The most important thing that Larry has taught me in our many years together is momentum — meaning when we are working on any project co-written or sole-written, we write every day, be it the weekend, weekday, Sunday, holidays. No days off until that first draft is complete,” Ossana tells me.

McMurtry still taps his stories out on his Swiss-made Hermes 3000 typewriter.

Wittingly or not, in describing McMurtry she provides an almost perfect warts-and-all distillation of Gus and Call.

“He is probably the most well-informed human I’ve ever known. He is essentially a database with an opinion. I do advise folks not to ask for his opinion unless they really want it,” she says. “I have often been asked whether Larry knows the women in his life as well as he knows the women in his novels. My response is that Larry knows and understands every character he has created, intellectually and emotionally, but when it comes to the real women in his life, he’s just as clueless as the next man.”

Although the miniseries is credited with reviving westerns at a time when their popularity was sagging, McMurtry wasn’t out to save the genre when he wrote Lonesome Dove. In fact, he’s been critical of those who romanticize the West. The book was in part an attempt to neuter well-established myths.

“People are nostalgic for the Old West, even though it was actually a terrible culture,” he told Texas Monthly in 2010. “Not nice. Exterminated the Indians. Ruined the landscape. By 1884 the plains were already overgrazed. We killed the right animal, the buffalo, and brought in the wrong animal, wetland cattle. And it didn’t work. The cattle business was never a good business. Thousands went broke.”

As an attempt to defuse Western mythology Lonesome Dove has been, of course, a glorious failure.

“The characters in that novel are simply too strong, backed up by decades of popular culture about the West,” he admits.

Despite all its violence, tragedy, and immorality — I find it instructive to note the final word of the magisterial western classic is whore — no one can read Lonesome Dove for the first or 15th time without experiencing a spasm of regret at having missed out on the last truly wide-open period of the great American adventure. Even if chances are high he or she would have died young or as part of some hideous calamity — characters expire by all sorts of grisly means in Lonesome Dove — who wouldn’t jump at the chance to saddle up with Gus’ and Call’s Hat Creek outfit for the drive to Montana?

That temptation, of course, is central to Lonesome Dove’s near-religious appeal. McMurtry’s genius is in allowing us to feel we’re not just reading about Western history. From page one, we’re part of it. Like staring at a photo of a departed loved one or holding a Bible that belonged to your great-grandparents, Lonesome Dove inspires the visceral pleasure that comes with feeling connected to a spiritual greatness.

Even if McMurtry doesn’t acknowledge it, that’s magic of the highest order. That lonesome cowboy on the horizon fading in the twilight? Turn the page. Look again. He may be gone, but somehow he never quite disappears.

McMurtry And Me

As Lonesome Dove fans celebrate its 35th anniversary, our writer reminisces about the lonesome antidote of Larry McMurtry’s earliest books.

I discovered Larry McMurtry in, of all places, a tiny village in rural Japan. I was just out of college and working as an ESL teacher. Instead of feeling exhilarated surrounded by the glitzy neon of Tokyo as I’d imagined, I ended up feeling stuck as the only foreign resident of an isolated mountain town in a part of the country known as the Japan Alps. I spoke no Japanese. Almost no one in town spoke English.

I eventually grew to love Japan. But my first six months there, when everything felt so unfamiliar, were among the dreariest of my life. The death of a family member and a confluence of small personal disappointments left me isolated and homesick. Years later a friend told me, only half-jokingly, that the letters I’d written home during this period read more like suicide notes.

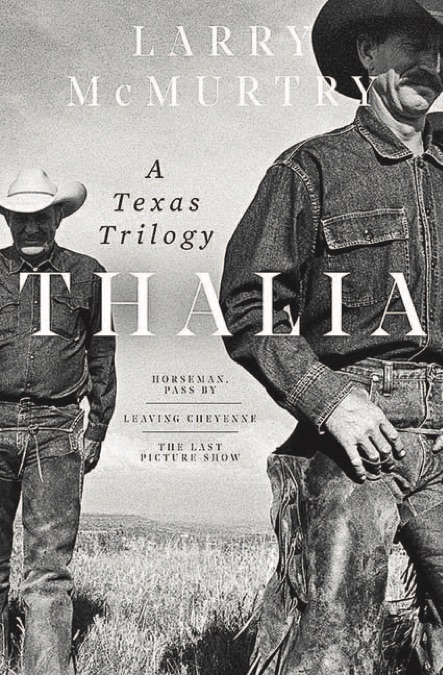

A trip to an English bookstore in the big city of Nagoya eventually brought me around. In a burst of excitement I bought 10 or 15 books to haul back to my tiny, unheated apartment. But it was three thin paperbacks by McMurtry — Horseman, Pass By; Leaving Cheyenne; and The Last Picture Show — that quickly stood out.

I’d never been to Texas at the time. I grew up in Southeast Alaska, which in terms of terrain and culture is about as different from rural Texas, or rural Japan, as it’s possible to find. But there was something so “American” in McMurtry’s vernacular that every time I picked up those books it felt like home. I read them three or four times and am sure I’ve never felt as patriotic, as wonderfully melancholy and misunderstood and American, in my entire life.

The great power of literature is that it can transport us to whole other worlds. It takes a genius like McMurtry to transport us to another world where we feel like we belong.

Each written before he was even 30 years old, those three books have since been bundled into an omnibus popularly known as the Thalia Trilogy. While I went on to treasure the cowboy epic Lonesome Dove and so many of McMurtry’s other books, it’s Thalia that I can still pick up and feel like I’m right where I ought to be.

For Larry McMurtry’s prolific screenplays …

Photography: Images courtesy Leann Mueller

From our August/September 2020 issue.