Colorado-based photographer Don Jones has captured cowboys, cowgirls, and Chief Sitting Bull’s great grandson through the archaic process of wet-plate photography.

After the Civil War, the country’s North-South orientation gave way to a new focus: Western migration. Explorers, miners, and settlers went west in waves — some of them carrying cameras with the idea of documenting the frontier, from landscapes to mining claims. Among the earliest of these photographers of the American West were Timothy H. O’Sullivan and Carleton Watkins, both of whom had to struggle with the wet-plate negative process and the bulky equipment that went with it. The process was not only unwieldy and difficult to control, but the use of poisonous chemicals made it dangerous. Well more than a century later, Colorado-based photographer Don Jones resurrects the archaic process to create stunning contemporary imagery with a striking vintage character.

A graduate of Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara, California, Jones assisted award-winning Vanity Fair photographer Annie Leibovitz in 1995 and 1996 while she was shooting athletes training for the Games in Atlanta for the book Olympic Portraits. After working on high-profile projects using state-of-the-art equipment, Jones found himself drawn to the earliest days of photography. Now immersed in the highly specialized 19th-century wet-plate photographic process, Jones uses an 8 x 10 Deardorff view camera and special lenses made in the late 1800s.

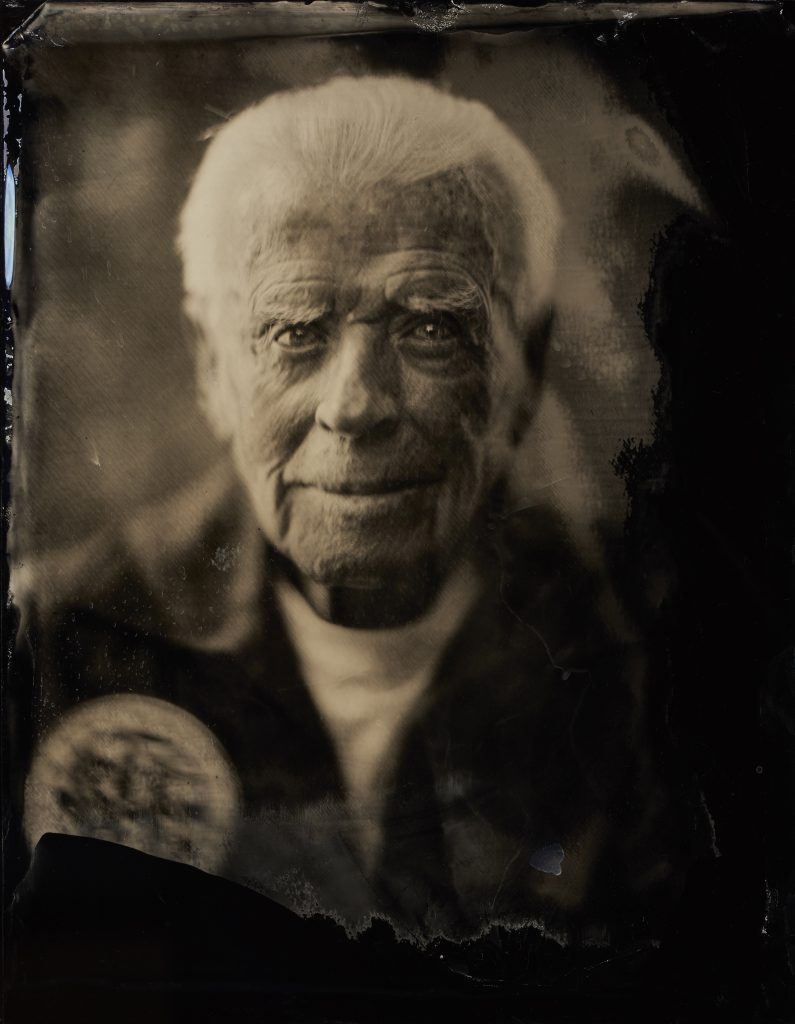

Don Anderson, One Nation Elder 94yrs old

Creating the wet-plate portraits requires that the photographic material be coated, sensitized, exposed, and developed within the span of about 15 minutes. His mobile rig allows him to travel to his subjects — who have included cowboys, cowgirls, and great-grandson of Chief Sitting Bull Ernie LaPointe — and capture them in authentic environments.

Cowboys & Indians: After success as a commercial photographer, why make the leap to wet plate?

Don Jones: I was classically trained as a commercial, not a fine art, photographer. Fine art photography comes from the heart. During my career I’ve photographed governors, senators, world-class athletes, and even actors, but this is the most difficult thing I’ve done in my career. My hope is to have this work eventually hanging in museums, and I plan on publishing several books using this process.

C&I: Tell us about the Deardorff camera.

Jones: I was introduced to the Deardorff camera more than 30 years ago, by a fellow photographer who was already deep into the process. I had never seen or heard of the Deardorff until then and was lucky to find a used studio portrait camera here in Colorado Springs. I sold that and bought a more mobile one, much easier to work with in the field: a 1963 8 x 10 Deardorff V8 field camera, with a Dallmeyer 2A 350 mm, f4.5 Petzval lens produced in London in 1890. All three lenses I use were made around 1890. The company was started a hundred years ago by Laban L. Deardorff. It is truly an iconic brand — I compare it to the Steinway.

You have to be a virtual chemist to understand this process. The instructor who I took classes with and revere so much, Quinn Jacobson, wrote a book called Chemical Pictures, which is literally a series of pictures that are mixed in a particular chemical fashion and react to the light. The chemicals, one of which is potassium cyanide, are tough to work with. I had to be registered with the DEA in order to purchase them.

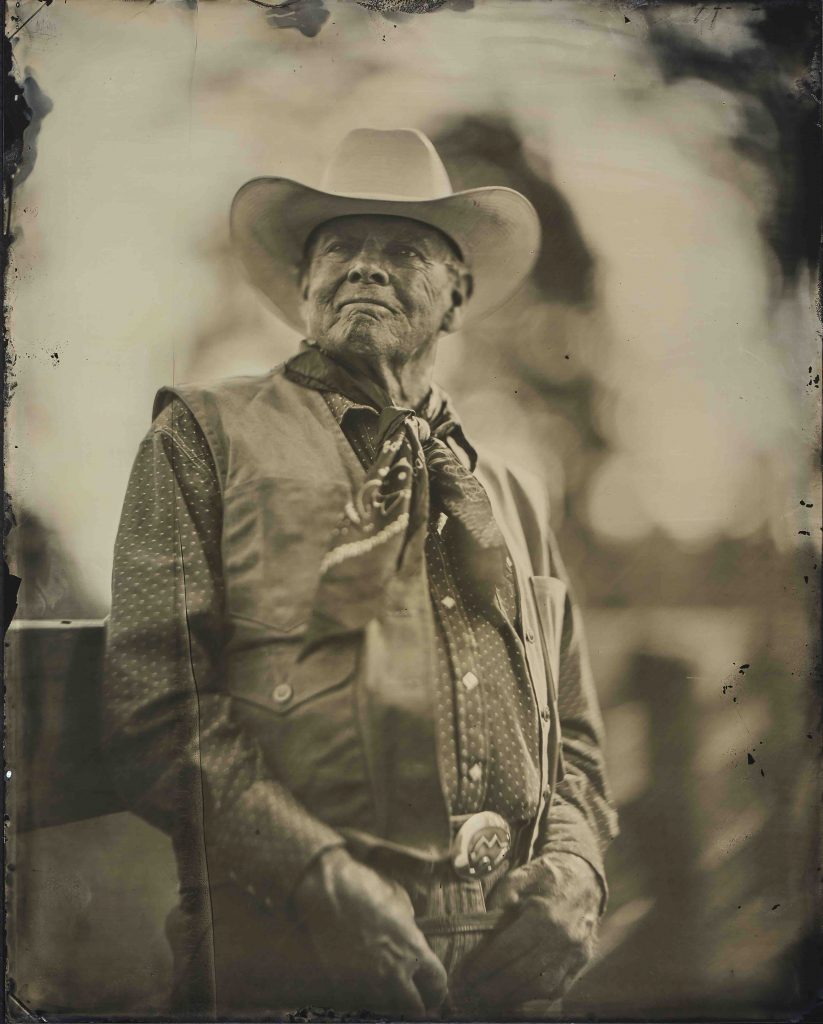

John Vance at his Ranch

C&I: How does this process compare with digital?

Jones: Two very different processes. With wet plate you can get great controlled images. But perhaps the biggest advantage is that in an age of digital photography, this is craft — a craft the photographer appreciates, and a craft that the subjects appreciate. It turns a portrait into a much bigger thing: a portrait that has a story and reimagines the past. This is not point and click; you have to plan the shot well in advance of taking the picture.

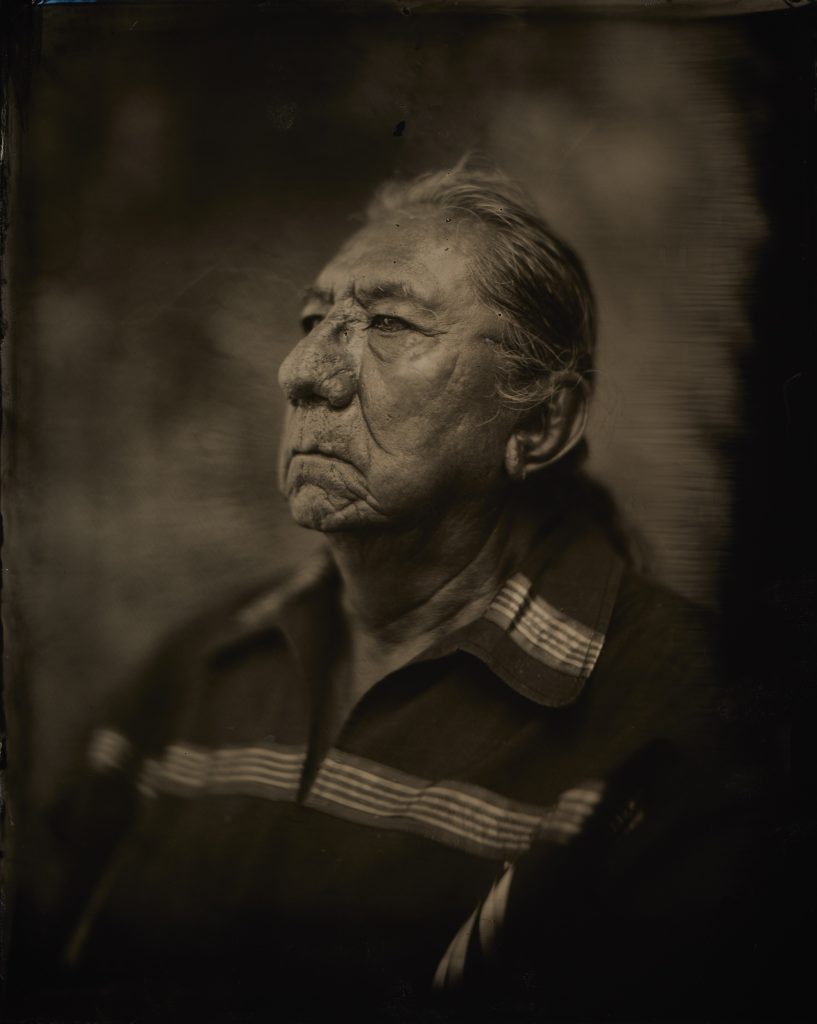

C&I: There’s an exciting story about your photograph of Ernie LaPointe. ...

Jones: In general, I want each subject’s story to be told through these portraits. Each photograph is a very deliberate and slow process, and each image I create takes time. You learn that you only get one or two opportunities to capture their nuance and expression.

Photographing Ernie LaPointe has been a real highlight of my career. He’s the great-grandson of the famed Lakota leader Chief Sitting Bull, which was recently proven by DNA tests. It was front-page news when the ScienceAdvances journal announced in late October that scientists had traced family lineages from ancient DNA to verify that Ernie, who is now 73, is most definitely Sitting Bull’s great-grandson and closest living descendant.

Ernie LaPointe, Sitting Bull’s Great Grandson

Sitting Bull was, of course, the great chief and medicine man who united the Sioux tribes of the Great Plains in the late-19th century and led a resistance against settlers. After he was killed by Native American police in 1890, an Army doctor at Fort Yates in North Dakota took a lock of Sitting Bull’s hair and wool leggings. It was apparently from that that they were able to trace the DNA. This proof should help Ernie get Sitting Bull’s remains repatriated from his current burial site in Mobridge, South Dakota, to a spot that he says had more cultural meaning to his great-grandfather.

C&I: Was the significance of his lineage palpable?

Jones: As Ernie and I walked to the set, I couldn’t help but think of the history I was going to make with my camera and darkroom. He sat perfectly still, not saying a word, looking like a warrior. After developing the authentic wet-plate collodion portrait, I realized how similar the image of Ernie was to the ones made of Sitting Bull in the 19th century.

Don Jones’ work will be on view March 10 – April 10 at Broadmoor Galleries in the Broadmoor Resort in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Visit him online at donjonesphotography.com.

From our February/March 2022 issue

Photography: (All images) courtesy Don Jones