With his filmography from 1939 to 1976, John Wayne evolved from actor into icon.

Stagecoach (1939)

John Ford’s masterwork, a sort of Grand Hotel of the plains, firmly established The Duke’s image as a tarnished but noble hero who speaks slowly and aims lethally. He’s The Ringo Kid — “Right name’s Henry!’’ — and he’s broken out of prison to avenge the death of his father and brother. Unfortunately, he hitches a ride on a stagecoach while the local sheriff is riding shotgun. Even more unfortunately, the trail runs through territory where Geronimo and his warriors are on the warpath. Wayne is courtly and compassionate in his scenes with Claire Trevor as Dallas, a shady lady recently driven from a nearby town by the local moralists. This being a 1939 movie, no one actually comes out and says Dallas is a prostitute, but all the respectable folks on the stagecoach shun her. Ringo, not being the least bit respectable, falls in love with her. But, then again, he admits to a checkered past all his own: ‘’I used to be a good cowhand,’’ he says, ‘’but things happened ... ’’

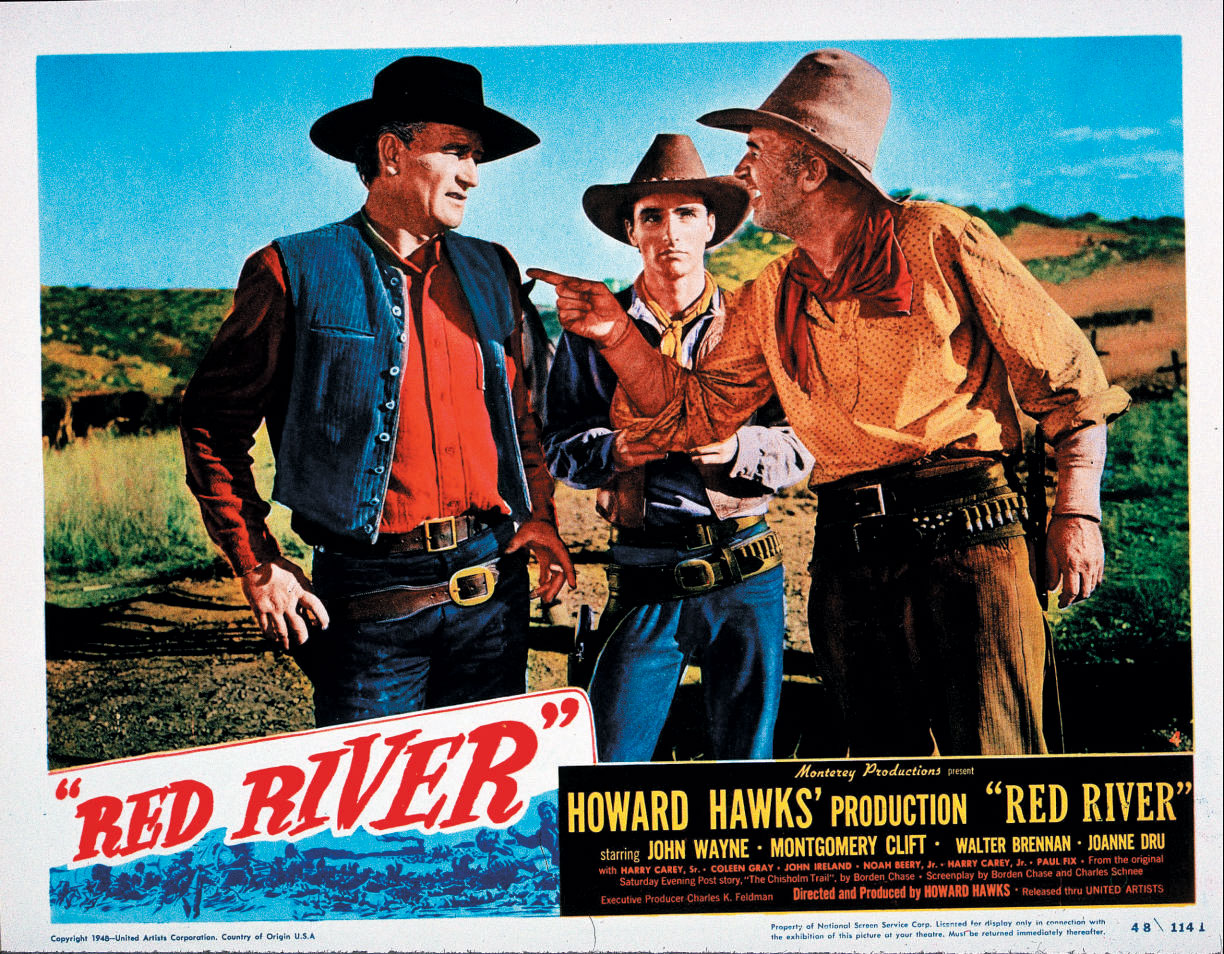

John Wayne may be remembered as an all-American hero, but that doesn’t mean he never slipped over to the dark side. Indeed, The Duke sounded positively proud when he explained to an interviewer, “I was playing [Charles] Laughton’s part in Mutiny on the Bounty in Red River.” No kidding: Wayne gives one of his darkest, most psychologically complex performances in Howard Hawks’ acclaimed Western, playing a cattle rancher who slowly evolves into a brutal, paranoid tyrant not unlike Laughton’s fearsome Capt. Bligh while leading a massive drive to Missouri. The upbeat ending is a cop-out — everything leads you to expect, even demand, a shootout between Wayne and the adopted son (Montgomery Clift) who leads a rebellion against his harsh rule. Still, Wayne rarely had a more richly textured role to play, and he rose to the challenge with extraordinarily impressive results.

3 Godfathers (1948)

Three hard-luck cattle rustlers (John Wayne, Pedro Armindariz, and Harry Carey Jr.) ride into a small town to try their hand at a new line of work: bank robbery. But shucks, these fellows are too good-hearted to be real bad guys — they’re even polite to the local sheriff (Ward Bond) while on their way to the heist. While riding across an unforgiving desert with a posse in hot pursuit, they stop to help a dying woman give birth, then vow to care for her orphaned infant. The sentimental streak is a mile wide — and the religious symbolism only slightly less conspicuous — in John Ford’s first filmed-in-color Western. But nevermind: Wayne has never been more amusing and endearing than he is here as a tough but tenderhearted galoot who awkwardly warms to the task of being a surrogate daddy for a needy newborn. It helps that — for a while, at least — he has two co-stars to share the parenting chores. Call this the original Three Men and a Baby, and you won’t be far off the mark.

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949)

The second chapter in John Ford’s so-called ‘’Cavalry Trilogy’’ — Fort Apache (1948) and Rio Grande (1950) are the others — has Wayne cast as Capt. Nathan Brittles, a career soldier who must complete one final mission before retirement: prevent a full-scale Indian war following the massacre at Little Bighorn. There is a mood of autumnal melancholy throughout this classic, as Ford and Wayne depict Brittles as representing an old guard that must, inevitably, make way for the new. For all its scenes of courage under fire and grace under pressure, this is a beautifully sentimental film, focused on rituals and rites of passage. Wayne is dead-solid perfect, combining hard-bitten professionalism and wistful, world-weary sadness in just the right increments.

Hondo (1953)

The one and only John Wayne movie filmed in 3-D — all the better to make audiences duck when arrows start flying — this gritty, grown-up Western (based on a Louis L’Amour story) remains, even in 2-D, one of The Duke’s most enduringly popular movies. As Hondo Lane, an Indian scout, ex-gunfighter, and dispatch rider for the cavalry whose best friend is his mangy dog, Wayne makes an indelible impression in an iconographic role, playing the rugged loner as surprisingly sympathetic to the Native American cause — with good reason, it should be noted — even while protecting a neglected woman (Geraldine Page) and her young son (Lee Aaker) from their increasingly (but not unreasonably) hostile Apache neighbors. Not surprisingly, Hondo takes a hankerin’ to the lady in jeopardy. So it’s not altogether unpleasant for him when she agrees to pretend she’s his wife — if only to keep an Apache chief (Michael Pate) from slaying our hero.

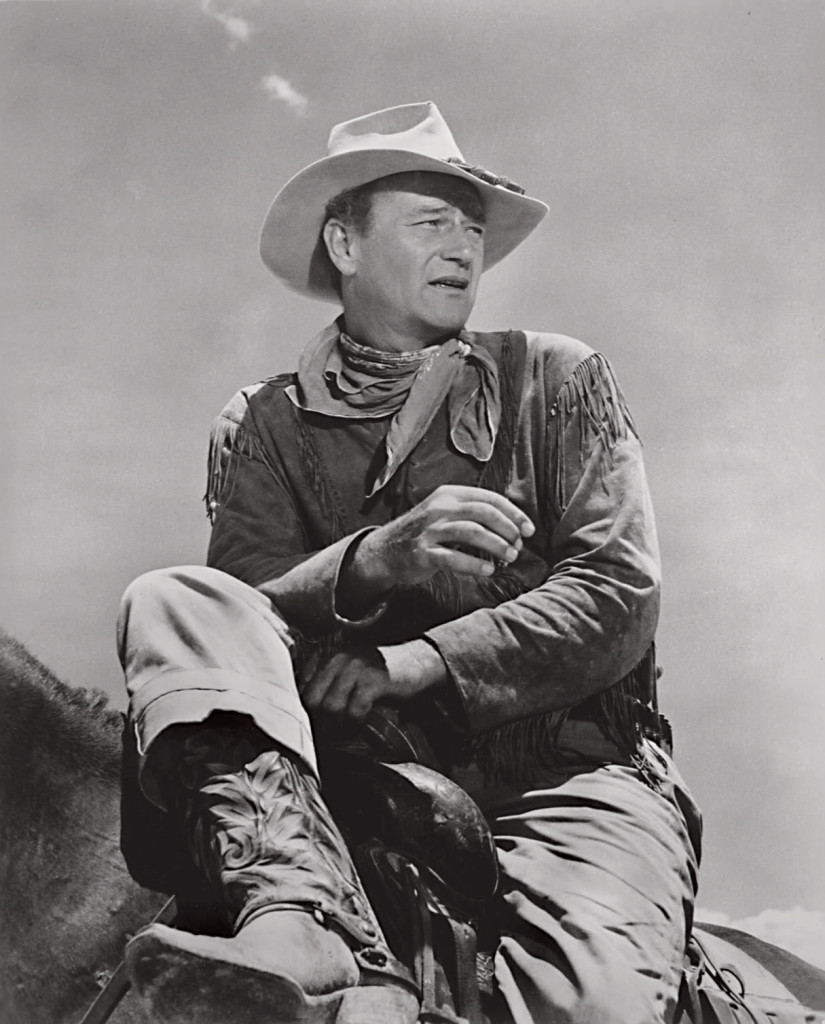

The Searchers (1956)

Everyone from George Lucas (Star Wars) to Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver) has been influenced by John Ford’s sprawling Western odyssey, in which Wayne gives the performance of his career as Ethan Edwards, a taciturn Civil War veteran whose search for a niece kidnapped by marauding Indians turns, over the course of several years, into a relentless quest for vengeance. Wayne and Ford dare to portray Edwards as not some noble embodiment of frontier justice, but rather as a brutal, mean-spirited racist who’s appalled by the very idea that his niece (Natalie Wood) is cohabitating with Chief Scar (Henry Brandon). For an uncomfortably long period, the audience is cued to expect that if Edwards ever does find Debbie, he will feel compelled to kill her. In the end, he overcomes his baser instincts and returns Debbie safely to her family. But as the famous final shot makes clear, Edwards himself will remain forever alone and apart from other men.

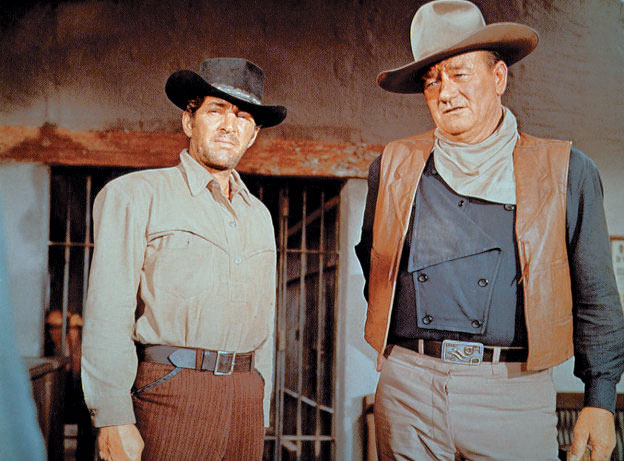

Rio Bravo (1959)

In one of the most purely entertaining Westerns ever made, Wayne is at his most ruggedly charismatic as John T. Chance, a small-town sheriff who’s determined to keep a killer in jail while waiting the arrival of a U.S. marshal. Trouble is, the killer’s brother has gathered together some mean-looking gunslingers, for the sake of launching a jailbreak. So Chance, usually a man who gets the job done by his lonesome, must rely on the help of some dubious professionals: Dude (Dean Martin), an alcoholic ex-deputy who’s deadly if and when he stays sober; Colorado (Ricky Nelson), a cocksure young cowboy who can back up his bold talk with fast guns; and Stumpy (Walter Brennan), a cantankerous old coot who’s tremendously loyal to Chance. Director Howard Hawks tells his familiar story with virile gusto and hearty humor in a movie much admired — and occasionally imitated — by directors as diverse as John Carpenter (who more or less remade it as Assault on Precinct 13) and Quentin Tarantino.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

Dismissed by many critics during its initial theatrical release, John Ford’s last great Western now is widely acknowledged as one of the filmmaker’s most heartfelt and fully realized works. James Stewart is a tad too old to be completely persuasive as tenderfoot Ransom Stoddard, an idealistic young lawyer who finds legalisms are of little use against a wild-eyed outlaw like Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin at his most sadistic). But Wayne is at the top of his form as Stoddard’s unlikely ally, a cynical gunfighter named Tom Doniphon. For all his gruffness, Doniphon emerges as a noble knight errant, a selfless hero who ultimately insists that Stoddard take credit for being the hero of the title. (Doniphon, of course, is the one who actually blasts the bad guy.) Stoddard goes on to become a successful politician, bringing the dubious values of civilization to the Wild West, while Doniphon fades into obscurity, becoming an anachronism long before his death. Ford sums it all up for us through a newspaperman’s final words: ‘’This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’’

McLintock! (1963)

The original advertising tagline says it all: “He likes his whiskey hard ... His women soft ... and his West all to himself!” Wayne gives a big, blustery, and bodaciously funny performance, brimming with seriocomic swagger, as cattle baron George Washington McLintock, the role that defined his on-screen persona for many Baby Boomers. McLintock owns all of the land and almost everything that’s built upon it in the Arizona town that has been named after him. But that doesn’t make it any easier for him to ride herd on his spirited wife (close friend and frequent co-star Maureen O’Hara) and their college-educated daughter (Stefanie Powers). And he’s scarcely more successful when it comes to anger management, especially when a farmer brandishes a lethal weapon and cues one of The Duke’s most memorable outbursts: “I haven’t lost my temper in 40 years — but pilgrim, you caused a lot of trouble this morning, might have got somebody killed ... and somebody oughta belt you in the mouth. But I won’t, I won’t.” Slight pause. “The hell I won’t!” And then he does.

True Grit (1969)

Wayne finally won an Academy Award by acting his age and playing “a one-eyed fat man,’’ grizzled lawman Rooster Cogburn, in director Henry Hathaway’s hugely successful, tongue-in-cheek Western. The Duke has a great deal of fun spoofing his own image, playing Cogburn as a seemingly unreliable drunk who can barely stay on his horse, much less operate his six-shooter. But when the chips are down, and the odds are against him, our hero proves just as capable as Wayne’s more sobersided characters. (Robert Duvall’s cocky Ned Pepper is just one of the varmints who learn the hard way that Cogburn’s aim is true.) Co-starring Kim Darby as a plucky 14-year-old girl who hires Cogburn to find her father’s killer, and Glen Campbell as a clean-cut Texas Ranger, True Grit ambles along at a unhurried pace, relying more on character than action to hold the audience’s interest. And make no mistake about it: Wayne is a real character here.

The Cowboys (1972)

Desperate times call for desperate measures. When cattle rancher Wil Andersen (John Wayne) finds his ranch hands have galloped off to the gold fields, he hires some school-age greenhorns to drive his herd to market. But when Andersen is killed by a vicious rustler (Bruce Dern), the boys must become gunmen to avenge his death. Director Mark Rydell, no fan of The Duke’s politics, admits that he originally didn’t want Wayne for this cult-fave Western. “So I surrounded him with a lot of hippie, pot-smoking crew members,” Rydell recalls. “I didn’t want him to be comfortable. But you know what? He was a gentleman, he was friendly. He was great with the kids, who were always around him. They would climb on him like a monkey bar on a playground. He always had time for everybody. And he taught me a lesson, an important lesson, in my life: not to judge too quickly.”

The Shootist (1976)

On January 22, 1901, legendary gunfighter J.B. Books (Wayne) rides into Carson City, where a local doctor (James Stewart) confirms his worst fears: “You have a cancer. Advanced.’’ At the time of its release, The Shootist discomforted many fans, who couldn’t help viewing it as an unwelcome reminder of The Duke’s real-life battles with “The Big C.’’ But now, decades after Wayne’s passing, this underrated Western can be better appreciated as a respectful elegy for a Hollywood professional of tremendous dignity and stature. (A nice touch: The opening credits are flashed over clips from some of Wayne’s earlier Westerns.) To be sure, the movie is not quite equal to the man it honors. But it does allow Wayne one of his very few opportunities to play a character who frankly expresses a fear of his own mortality (“I’m a dying man, scared of the dark!”) even while remaining true to his personal code: “I won’t be wronged. I won’t be insulted. I won’t be laid a-hand on. I don’t do these things to other people, and I require the same from them.” Directed by Don Siegel (Dirty Harry), The Shootist is deeply moving as it symbolically ends an era of history, and literally ends an historic screen career.

From the July 2007 issue.