A tribute to the iconic actor in honor of his 100th birthday.

To celebrate the centennial of John Wayne’s birth, savor the precise moment when the man became immortal. Just pop a DVD of John Ford’s Stagecoach into your disc player, and you can witness the movie-magical transformation of actor into icon.

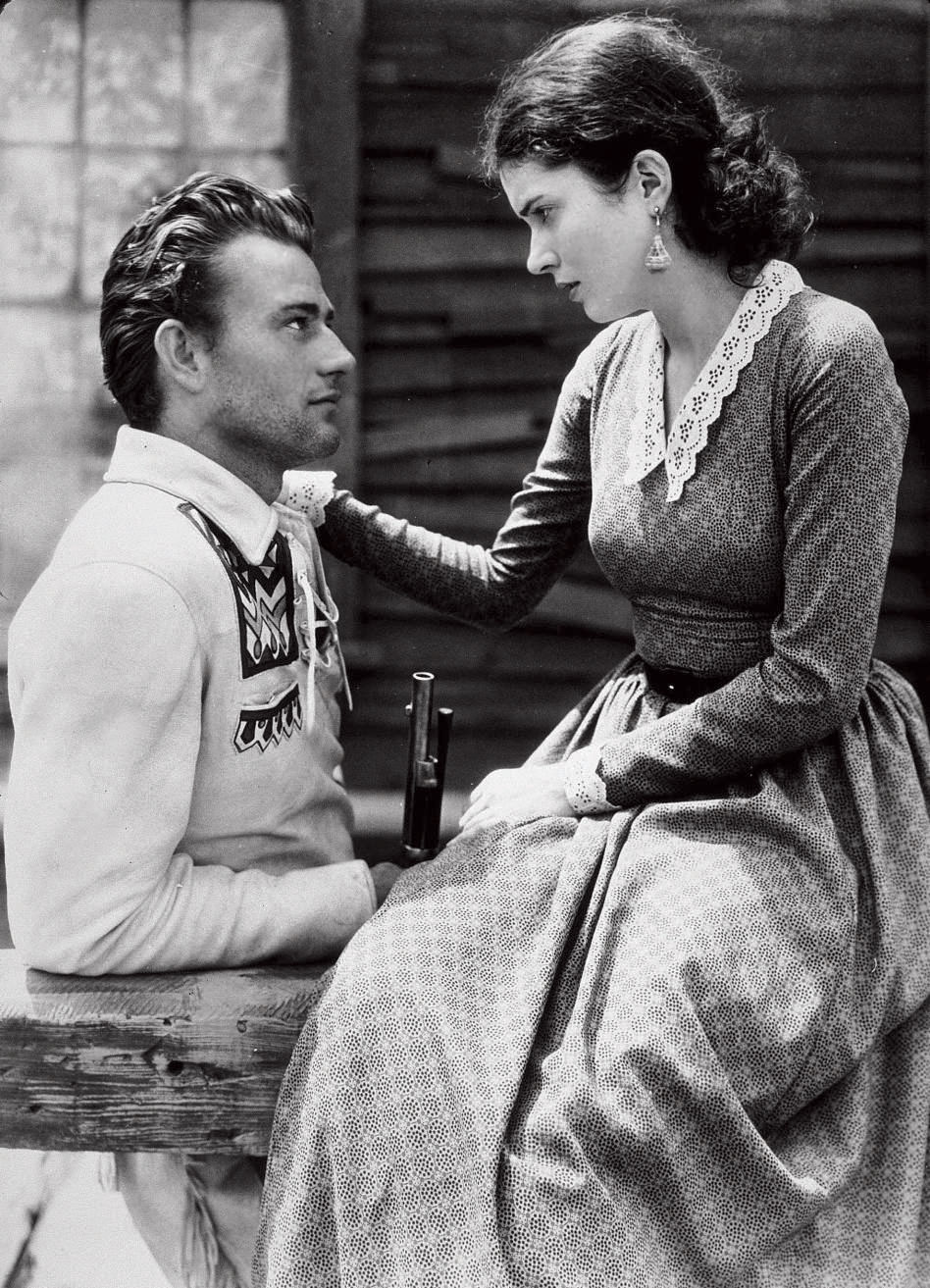

Ford’s 1939 masterwork, arguably the first “adult” Western of the talking-pictures era, was a serendipitous second chance for the rangy fellow born May 26, 1907, as Marion Robert Morrison. Nine years earlier, The Man Who Would Be Duke had grabbed at the brass ring as the lead in Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail — but that ambitious frontier epic turned out to be a career-stalling flop. Indeed, when Ford first approached Hollywood movers and shakers to secure backing for Stagecoach, he repeatedly was told that Wayne, his leading man of choice, lacked sufficient star quality for the key role of The Ringo Kid, a boyishly handsome gunfighter who breaks out of prison to avenge his murdered father and brothers.

Fortunately for all parties involved, Ford held firm, ignoring suggestions that he re-cast the part with, say, Gary Cooper (or even Bruce Cabot). Eventually, producer Walter Wanger relented, despite his misgivings about casting “a B-movie actor” in an A-list production. And that’s why, several minutes into Stagecoach, Wayne gets to make what film director and historian Martin Scorsese aptly describes as “one of the best entrances in film history.”

Much like the passengers in the conveyance of the title, we get our first glimpse of Ringo as he stands on the road, flagging down a ride. As he spins a rifle like a six-gun, the camera rapidly tracks toward him, then frames him heroically, almost worshipfully, in a flattering close-up. That the image briefly goes out of focus actually enhances the scene’s impact — you get the feeling that even the cinematographer is awed by the sight of such studly formidability. The die is cast, the legend is born.

But it doesn’t end there. Ringo quickly establishes himself as a friendly and forthcoming fellow, even when dealing with a sheriff who feels obligated, albeit reluctantly, to arrest the outlaw. He’s a perfect gentleman when dealing with the imperfect heroine (Claire Trevor), a golden-haired, golden-hearted prostitute who brightens incandescently whenever the naive cowboy refers to her as a “lady.” (When snooty fellow passengers avoid her at dinnertime, Ringo simply assumes they’re insulting him, not her, and drawls, “Well, I guess you can’t break out of prison and into society in the same week.”) But make no mistake: Ringo leaves no room for doubt that once the arduous stagecoach journey concludes, he’s quite capable of minding his own bloody business at the end of the line.

Such is the indelible image of the youthful John Wayne, the assured yet self-deprecating hero who could give as soulfully affecting a performance as any Western star who ever rode hard and shot straight in the most American of movie genres. Expanding upon the archetype established by such silent-movie masters as Tom Mix and William S. Hart, Wayne in Stagecoach conveys the very essence of the square-jawed, slow-talking gunfighter who’s quite willing to hang up his shootin’ irons, who’s even agreeable to mending his ways and moving to a small farm someplace with a good woman by his side — but not before he settles some unfinished business with the varmints who terminated his loved ones. Why? Because, as Ringo tersely notes, “There are some things a man can’t run away from.”

The part fit Wayne so well that long after he evolved into a gray eminence he continued to recycle various and sundry aspects of the performance that first established his superstardom. He did it so frequently, and so successfully, that his name came to define an entire genre — as in, “I love John Wayne movies!” — even while demonstrating a chronically under-rated range and versatility. (According to Hollywood legend, Ford saw Wayne’s atypically dark performance as a tyrannical cattle rancher in Red River and cracked, “I never knew the big son of a bitch could act!”) Constantly repeating yourself, of course, is part of what being a superstar is all about — giving your audience what they want, what they expect and, perhaps, what they need. But Wayne more often than not gave much more.

As Andrew Sarris, the dean of American film critics, noted as early as 1969, “Wayne’s performances in The Searchers, The Wings of Eagles, and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance are among the most full-bodied and large-souled creations in the history of cinema ... No one has suggested that his acting range extends to Restoration fops and Elizabethan fools. But it would be a mistake to assume that all he can play or has played is the conventional Western gunfighter.”

Through his entire film career — but especially in many of his great Westerns — Wayne personified an all-American amalgam of unshakable confidence, understated authority, and effortless grace under pressure. All that, plus a healthy dose of gruff wit and megawatt charisma. He usually played men who turned to violence only with great reluctance, and never — well, okay, hardly ever — without provocation. (In this context, the savage characters he portrayed in Howard Hawks’ Red River and Ford’s The Searchers are exceptions that prove the rule.) Time and again, he was a tough guy who didn’t need to act tough, a larger-than-life hero who felt little need to prove himself to anyone other than himself.

Howard Hawks, who directed him in no fewer than five films, said it simply and succinctly: “John Wayne represents more force, more power, than anybody else on the screen.” Amen, pilgrim.

From the July 2007 issue.