The Academy Award-nominated actor is best known for one gasp-inducing moment — when he pulled the trigger on an unarmed John Wayne in “The Cowboys.”

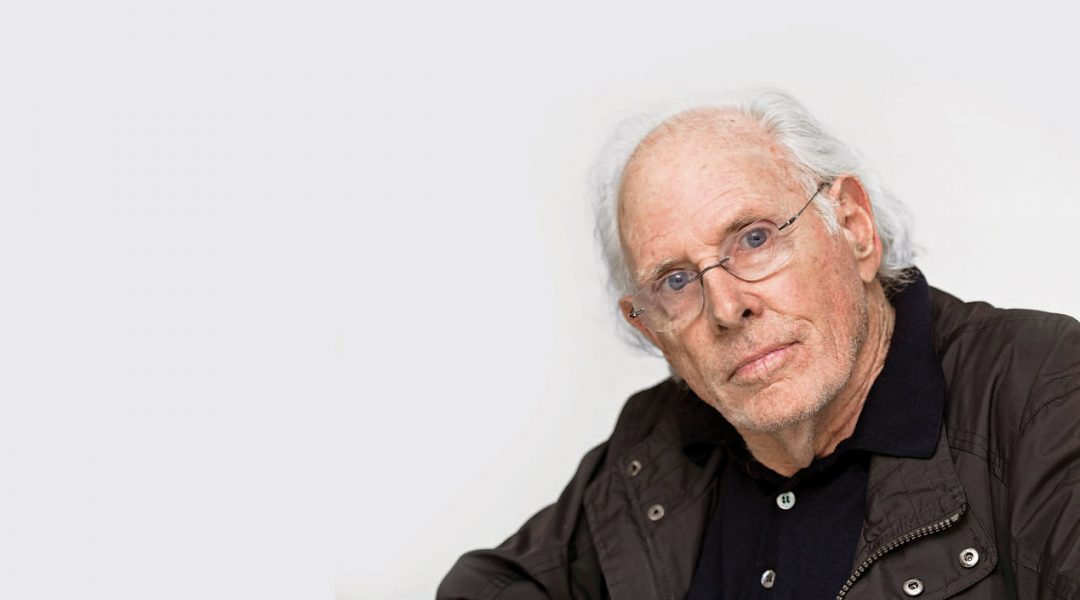

Bruce Dern knows you probably will never forgive him. But he’s not the least bit sorry for what he did.

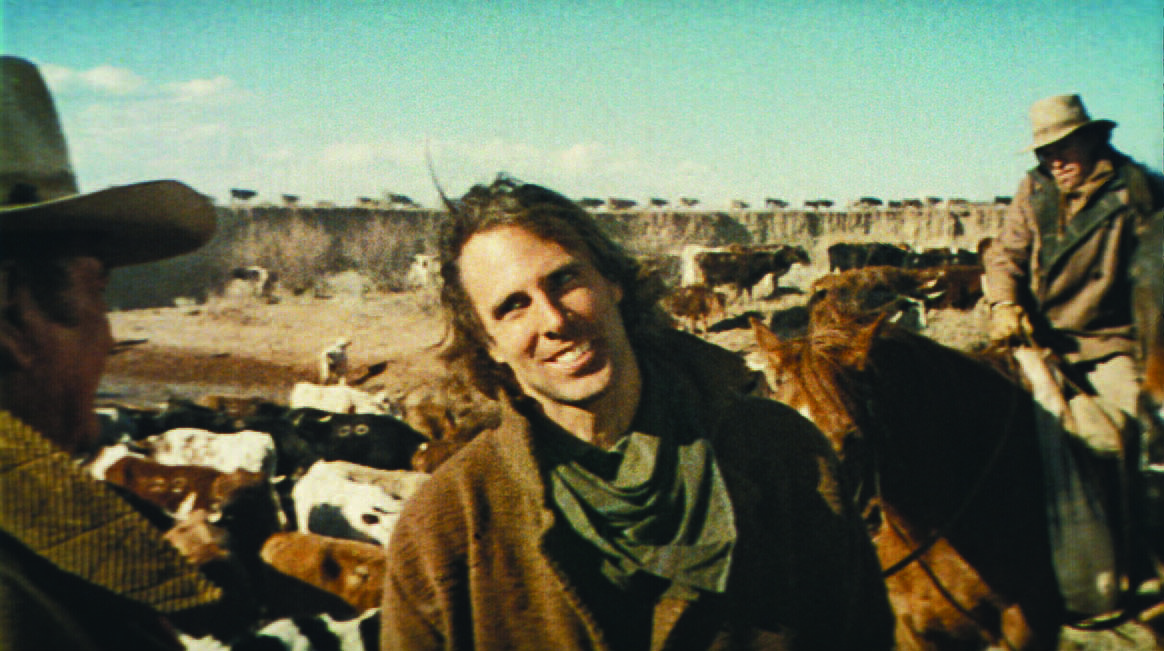

Indeed, in his autobiography — titled, only half-jokingly, Things I’ve Said, But Probably Shouldn’t Have: An Unrepentant Memoir (Wiley, 2007) — Dern sounds positively proud of the most dastardly deed he’s ever committed on-screen: gunning down an unarmed John Wayne in front of a gaggle of young buckaroos in The Cowboys (1972). The first time he saw the movie at a public screening, Dern recalls, was “the only time I’ve ever been in a theater watching a film I was in where I heard an audience gasp. They actually gasped.”

Chalk it up as one of many times the TV and film veteran has made a profound impact throughout his career spanning nearly six decades. Like many actors of his generation, Dern earned his spurs playing small parts in TV dramas such as Wagon Train and Gunsmoke before graduating to standout supporting roles in feature films. He attracted attention in such movies as Hang ’Em High (1968), Support Your Local Sheriff! (1969), and They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1969) before dispatching The Duke.

Dern then went on to savor critical acclaim for his work in The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), Smile (1975), Family Plot (1976), and Black Sunday (1977). He earned Academy Award nominations for his performances as a troubled Vietnam vet in Coming Home (1978) and a cantankerous senior citizen in Nebraska (2013). Now, as he enjoys a career renaissance sparked by the latter film, the 79-year-old Chicago native is looking to add to his list of accloades his performance in Quentin Tarantino’s latest, The Hateful Eight, as Gen. Sanford Smithers — a role written especially for him.

Along with an ensemble cast that also includes Kurt Russell, Samuel L. Jackson, Walton Goggins, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Michael Madsen, Tim Roth, and Demián Bichir, Dern enables Tarantino to tell a twisty tale of deception and death in an isolated stagecoach way station, where a motley crew of characters is stranded by a blizzard — and left to bring out the worst in each other.

We recently caught up with Dern to talk about The Hateful Eight and his other outstanding credits (including, of course, The Cowboys).

© 2015 The Weinstein Company. All Rights Reserved.

Cowboys & Indians: Many of our readers — even some who’ll never forgive you for shooting John Wayne — have fond memories of the comic western you made with James Garner and director Burt Kennedy, Support Your Local Sheriff! Do you rank that movie among your favorites?

Dern: Oh, I loved it, loved it. I worked with Jim Garner again later when we did a miniseries called Space. And I have to say Garner was really one of the all-time champion guys. I mean, he just really always knocked me out. He was very polite; he was a wonderful athlete. He’d been to Broadway. As a matter of fact, he was on the jury in The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial on Broadway. He was just real nice.

And Burt Kennedy was a great guy, too. Burt wrote and directed a movie called The War Wagon, which starred John Wayne and Kirk Douglas and I played a little tiny part in. Then he and a guy named Bill Bowers wrote the script for Support Your Local Sheriff!, and Burt directed it. And they were great. I mean, they were craftsmen. No one gives them credit for what they did, and now they are easily forgotten and everything. I just spent seven months with the only other guy I ever knew who really appreciated them and knew what they did and everything. And that was Quentin. Quentin loves Burt Kennedy and all of them, and he knows all of them. He’s the absolute best movie buff that there ever was.

That was one of the big things that I absolutely loved about the Hateful Eight shoot, the fact that every day, Quentin and I, for about 170 days we were together, we would play quiz games. I’d come in, I’d say, “OK, give me three Guy Stockwell movies.” He never missed three for anybody I ever gave him.

C&I: Looks like there’s a pattern here. First Alfred Hitchcock gives you a small role in Marnie — and then, later on, he gives you a much bigger role in Family Plot. Burt Kennedy casts you in The War Wagon — and then you get Support Your Local Sheriff! With Tarantino, you had a brief role in Django Unchained — and now you’re a major player in The Hateful Eight. It’s almost like they wanted to audition you before they gave you bigger parts.

Dern: [Laughs.] Well, I think with Hitch, the situation was, when I did Marnie in ’63, I wasn’t anybody yet. The main thing I’d been in was a little TV series called Stoney Burke. It starred Jack Lord, and he had two little sidekicks, Warren Oates and myself. It only ran a year. But for some reason, Mr. Hitchcock — who oversaw his own television series much more than anybody ever knew — saw me in it. So he cast me in a couple episodes [of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour] and Marnie.

Of course, Quentin wanted me to tell him stories about working with Hitchcock. [Laughs.] Quentin loves to have me tell stories about whatever it is I’ve been in. I’m extremely fond of him, and I feel he’s kind of fond of me, so I appreciate that. He wrote me a wonderful thing to do, you’ll see, in The Hateful Eight. He wrote us all great parts, because the guy can just [bleeping] flat-out write, not to mention direct, and do anything else he wants to do on the set. But he was always interested in the things that Hitch would come up with.

C&I: So what did you tell Quentin Tarantino about working with Alfred Hitchcock?

Dern: Well, the first day on the set of Family Plot, I pulled my chair right up next to Hitch and sat down. And I’m a little irreverent — and maybe a little off-putting, I guess — but I said, “Hey, bud, the drill with me is this: I’m going to sit here every day for 11 weeks, and if you’re bored with me, just tell me. I won’t talk, but I won’t leave. I’m not going to miss 11 weeks with you.” And he said, “That would be fine, Bruce. Sit right down.”

And then I said, “Hitch, why am I here? Why did you choose me? I mean, it’s a wonderful break in my career, but you’re not my agent or manager and everything else.” He said, “Well, first of all, Bruce, Mr. Packino wanted too much money. He wanted a million dollars.” Hitch doesn’t pay a million dollars. Even Miss Andrews and Mr. Newman didn’t get a million dollars from Hitch [for Torn Curtain]. I said, “I see, but that still doesn’t explain it. I don’t quite get what you’re telling me.” He said, “Well, first of all, all [Italians] should have their names spelled phonetically.” Suddenly I realized — Mr. Packino was Al Pacino.

Then he said, “And second of all, the legitimate reason you’re here, aside from the financial gain in employing you instead of some dreadful person that might not do as good a job as Mr. Packino certainly would have, is you’re entertaining. In my office, I have 1,242 [photos of actors] on the bulletin board, but none of them are interesting.” He says, “You’re here because you’re unpredictable and you are the only actor in your generation who appears to me to be unpredictable, and yet we like you. And that’s why you are here.”

C&I: So what can you tell us about The Hateful Eight? We know Quentin Tarantino has said the movie he wound up making is in many ways different from the early-draft script that was leaked onto the Internet a while back. But it’s still a movie about strangers stranded at a stagecoach way station, right?

Dern: What the man did is — he made an opera. I think there have been three movies in my life that I’ve felt were operas. I haven’t seen this, so I’m no judge of what it’s going to be. But I know what was shot, and so does everybody else who was on the set with us. The two operas I’ve seen were Lawrence of Arabia and The Godfather Part II. And now, hopefully, this. By opera, I mean, it’s not bigger than life, because there’s no overacting, there’s no over-the-top stuff in this movie. He casts the characters very meticulously. But it’s an opera.

Basically, it’s in five acts. The first act is the arrival of the stagecoach at Minnie’s — Minnie’s being the name of the way station, Minnie’s Haberdashery — and how the guys got on the stagecoach in the first place. You’ve got Kurt Russell, who’s a bounty hunter, and Jennifer Jason Leigh, who’s his prisoner who’s handcuffed to him. He is taking her to the county seat, to hang her, because she has a $10,000 reward on her head, because she used to have this gang. Along the way, they pick up two other people. One is Sam Jackson and one is Walton Goggins. When they arrive at the place, there are already five other people there — four that were on another stagecoach and myself. I was not on either stagecoach. I was there because I was on the stage that came the day earlier, and then they couldn’t get a stage out because of the blizzard.

When they get into it, the crux of the story is, nobody in this room is anywhere close to who they say they are. Except for me. I am basically the truth in the film. I am a Southern general, in full uniform, who has traveled all the way from Mississippi and Georgia to go out and get a proper burial site and put a memorial for my son, who died out there about a year earlier.

C&I: Do you still run into people who are upset with you — who actually are angry at you — because you played the guy who shot John Wayne in The Cowboys?

Dern: No question. But I knew that would happen. I knew on the day when I had to shoot him, when we did that scene, that he had never even had a bullet squib put on him before in his career. You know, he got shot in Sands of Iwo Jima. I think he got killed by some sniper. But this was the first time he actually had a squib put on him, where it was going to be close to his skin and everything else. [Laughs.] I remember he leaned into me at about 8:15 a.m. that morning, reeking of Wild Turkey 101, and said, “Is it gonna hurt?” And I said, “Duke, they’re gonna blow your [bleeping] chest off. Get a metal protector to put underneath those squibs so the squibs aren’t next to your skin.” “Oh, how do I do that?” I said, “How do you do it? Order the effects man, like you order everybody else, to go ahead and do that for you.”

Then, after he got all fitted up, he told me: “Oh, I want to remind you of one thing. When this picture comes out, and audiences see you kill me — they’re gonna hate you for this.” I said, “Maybe. But at [UC] Berkeley, I’ll be a [bleeping] hero!” He laughed at that. And then put his arm around my neck, turned me to the crew — there’s about 90 people there where we shot the thing, getting ready to do the scene — and he said, “That’s why this [bleep] is in my film. Because he understands that bad guys can be funny. If they weren’t, why would we be talking about them 150 years later?”

C&I: You actually filmed your scenes in The Cowboys during a break in another movie you were shooting at that time, right?

Dern: Yeah, Silent Running. And there’s a story there. One day, Wayne says to me: “Thank you for getting out of that other movie ... what’s it called? Something about toys in the sky?” Actually, I was dealing with robots on a space station. But I said, “Oh, yeah. It’s called Silent Running.” And he said, “They already did that movie.” I said, “What do you mean, they already did it?” He said, “Clark Gable was in it.” [Laughs.] I come to find out he was thinking of Run Silent, Run Deep. But that was a submarine movie, for God’s sake!

C&I: Were you at all intimidated by The Duke?

Dern: I might have been. But right at the start, he says to me, “I want you to do us a favor.” He was including himself, [director] Mark Rydell, and the scriptwriters. He said, “From now on, consider me to be somebody you can publicly kick the shit out of 24 hours a day on the set. Because I want these little kids [playing the cowboys of the title] to be absolutely terrified of you.” He gave me carte blanche to just treat him like a turd. So I was on him, talking back to him and stuff, for the few days I was there. And he would do things like call out: “Hey, Mr. Dern, would you get over here?” I thought, Hey, John Wayne gives you a “mister” status. My first day, he’s calling me mister. How about that? That’s pretty cool.

C&I: And now you’re the grizzled veteran — the icon — who’s working alongside the relative newcomers like Walton Goggins from Justified, who costars with you in The Hateful Eight. You could say he’s a character actor in the Bruce Dern tradition.

Dern: You don’t know how many times Quentin would say that to him in front of me. And Walton says a lot of other people have told him the same thing. But let me tell you: Walton can bring it. Walton is really gifted. And when people realize who the real Walton Goggins is, and somebody takes those qualities and makes a movie about them with him, then he’s home free for the rest of his life, because he is a unique individual. And he is basically an honest man.

As is another guy in this movie — Sam Jackson. He’s talented; he’s the whole package. But as a human being, he’s even a bigger package. He and Walton Goggins both wrote me the most beautiful letters that I’ve ever received in my life after I finished on the film.

C&I: Sounds like there was a lot of respect and admiration among the professionals on this set.

Dern: That’s right. You know, I am in a chair every second of every scene that I’m in in the movie. I never leave the chair by the fire, ever. It’s written that way, it stays that way, and it was shot that way. And I was really thrilled when I would look up after a take with, say, just Walton and I in it, and the others could have been in their dressing rooms or wherever, because they weren’t going to work for the next two or three hours. But I would look up after a take, and every one of them was on the set watching the scene. That’s the greatest compliment I’ve ever had.

C&I: One final question. What did you enjoy most about making The Hateful Eight? Was there a particular day when you felt especially pleased, especially satisfied with what you’d done?

Dern: For me, it was every day. And I’ll tell you why. When I left the set, after my last day on the film, I went up to Quentin, and I thanked him for giving me the opportunity to get better. I mean that. Not just because he writes it, and because he’s there, but he writes for you to potentially do better than you’ve ever done. That’s why he casts you. I mean, he doesn’t cast you to be better — he casts you because you were right for what he wants you to do, for the character. But he also roots for you, as your director, and gives you an opportunity — an arena, if you will — to come forward and do stuff.

I would say that in my entire career, which has gone — I don’t know, 58 years. Well, 59 years, I guess. But every now and then, you have a magical thing happen to you on the set of a movie. Well, I only had this happen three to four days in my career before The Hateful Eight. And I tell you: On Hateful Eight, I had it every single day. And that is why I was excited to go to work, every single day.

From the February/March 2016 issue.