The dynamic director-actor duo of John Ford and John Wayne made some of the greatest films of all time. We rank 14 of our favorites.

In a 1965 interview, John Ford was asked, “Are there certain of your films which you prefer?” His response: “Of course. All of the films in which my friend John Wayne played the main character.” Ford is not alone in that sentiment.

The professional partnership — of Wayne as star, Ford as director — created some of the most respected and admired films ever made. Their association dates back to the 1920s, when Ford was making silent films and Wayne was a student at the University of Southern California. Before he was the most popular western actor in Hollywood, The Duke served as a prop man, stuntman, and extra in several Ford productions, including Four Sons (1928), Strong Boy (1929), and The Black Watch (1929).

But it’s the 14 films starting with Stagecoach that established the Ford-Wayne collaboration as one of the most significant in the history of motion pictures. Here are our rankings of these movie milestones, from most essential to least successful.

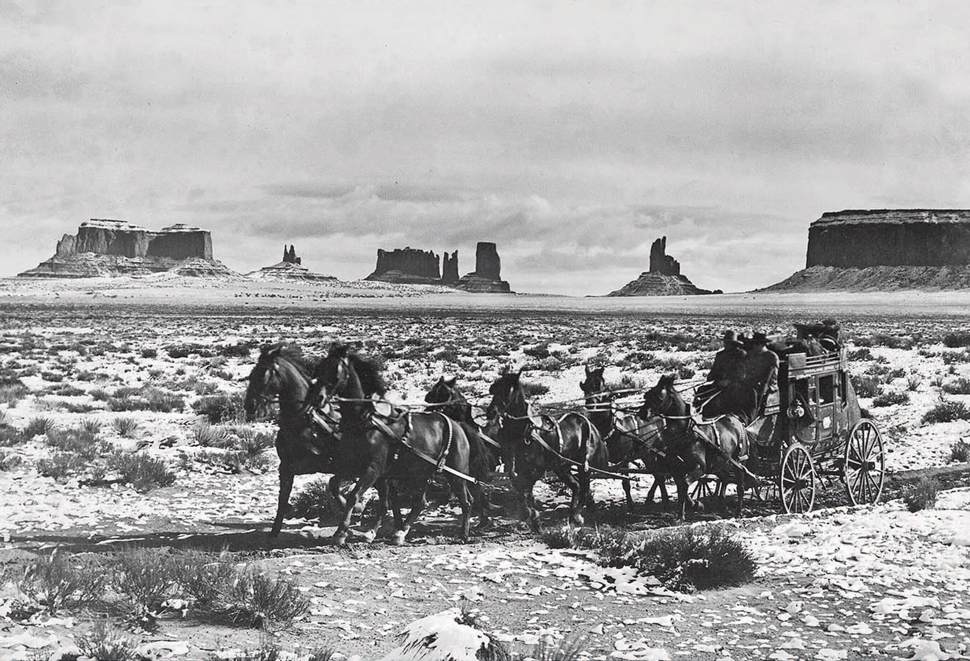

1. Stagecoach (1939)

One could make a convincing argument for flipping Stagecoach — the tale of a group of strangers on a perilous trip together through Geronimo’s Apache territory — and The Searchers in the No. 1 and No. 2 spots. But it’s also debatable whether The Searchers would ever have existed, or have been the classic it was, had Stagecoach not established the template for intelligent character-driven westerns — or had not elevated John Wayne from B-list cowboy to A-list actor.

Frank S. Nugent, who wrote The Searchers and collaborated with John Ford on many films, recognized the significance of Stagecoach but couldn’t resist asking Ford the one question that occurred to many viewers: “One thing I can’t understand about it, Jack. In the chase, why didn’t the Indians just shoot the horses pulling the stagecoach?”

Ford’s response: “In actual fact that’s probably what did happen, Frank, but if they had, it would have been the end of the picture, wouldn’t it?”

2. The Searchers (1956)

For many it’s the great western. With its complex moral themes and spectacular visuals, The Searchers transcends genre and has been embraced by a generation of filmmakers from George Lucas to Martin Scorsese as a masterpiece of visual storytelling. Wayne won the Oscar for True Grit but deserved it for his uncompromising portrayal of Ethan Edwards, an obsessed, embittered racist who earns his redemption in one unforgettable moment of compassion. Audiences feared the worst when Ethan stood over the cowering figure of his niece, who had adopted the ways of the Indians who abducted her. But then he reassures the terrified girl with four words now familiar to every western fan: “Let’s go home, Debbie.” The film’s final image, of Wayne framed in the doorway just outside the Edwards’ home, is one of Ford’s most revered shots.

3. She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949)

Working from a color palette inspired by Frederic Remington, Ford created scenes so striking they earned an Academy Award for cinematographer Winton C. Hoch. In addition to Monument Valley in Technicolor, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, the second in the cavalry trilogy, also challenged Wayne, then 42, to play a man in his 60s. His quiet strength and inherent authority were well-suited to Capt. Nathan Brittles and the role showed The Duke’s acting chops. Next to The Searchers, this was the most surprising of his Oscar nomination omissions; however, he was nominated that same year for Sands of Iwo Jima.

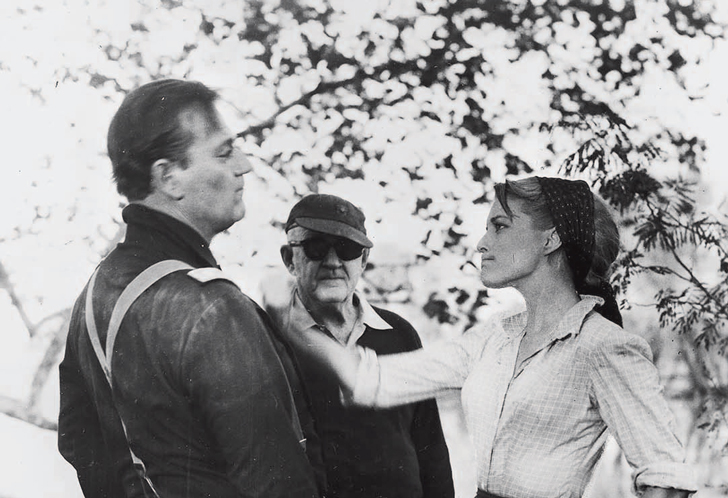

4. The Quiet Man (1952)

The highest-ranking non-western on our list, The Quiet Man is a St. Patrick’s Day perennial and proof that crusty old John Ford could be as sentimental as Frank Capra. Even the character names were taken from the director’s family tree. The theory that Wayne was Ford in front of the camera is most clearly realized here in the tale of a former boxer (Ford played fullback and defensive tackle) with a dark secret who returns to his mother’s (fictional) village of Innisfree (Ford’s mother was from the Aran island of Inishmore) and courts the feisty Irish lass of his dreams (memorably played by Maureen O’Hara). The Quiet Man was also a welcome reminder that Victor McLaglen had more to offer than comic relief on a military outpost: He won an Academy Award in 1935 for The Informer, another story set in Ireland.

5. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

As in Fort Apache, where Lt. Col. Owen Thursday’s folly is portrayed to the media as a daring military maneuver, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance plays upon the differences between facts and legends, a prominent theme in America’s frontier history. Wayne gives one of his signature performances here, his dismissive “pilgrim” reference to James Stewart becoming even more famous through Rich Little impressions. This is one of the more intimate of the Ford-Wayne collaborations, with much of the story unfolding on interior sets and not in wide-open spaces. The cast, freed from having to compete with magnificent Monument Valley vistas for the viewer’s attention, carries the film admirably.

6. Fort Apache (1948)

Not only the first of the cavalry trilogy, Fort Apache is one of the first Ford westerns where his early training as a painter is apparent in the Monument Valley visuals. All of the elements that distinguish a Ford western come together here in service to an outstanding Frank S. Nugent script, based as all the cavalry films are on the stories of James Warner Bellah. As with many of the director’s masterpieces, Fort Apache was the result of laborious preparation, followed by rapid production; Ford worked six months on the shooting script and the preproduction setups, and completed filming in just 44 days.

7. They Were Expendable (1945)

A fitting tribute to what would later be called “The Greatest Generation,” They Were Expendable relates a then-recent chapter in military history that resonated with decorated Navy man John Ford: the role of PT boats in World War II and how they progressed from glorified mail carriers to sinking enemy cruisers, albeit at a heavy cost. Wayne plays second fiddle here to Robert Montgomery, with able support from Donna Reed.

8. 3 Godfathers (1948)

The oft-told story about three men who encounter a baby during the Christmas season gets perhaps its best treatment since the Bible in this sentimental holiday tale. Garnering mixed reviews upon release, 3 Godfathers has become a yuletide tradition for many western fans and is often the first Ford-Wayne film many youngsters see. Any film that launches a future movie fan toward Stagecoach and The Searchers, and away from slasher films and slacker comedies, deserves all the recognition it can get.

9. Rio Grande (1950)

The final installment of Ford’s cavalry trilogy also features the first pairing of John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara. And despite the best efforts of Harry Carey Jr. in comic relief and Ben Johnson’s scene-stealing expertise, Rio Grande works because of the complex marital relationship between Col. Kirby Yorke (Wayne) and Kathleen (O’Hara). The film’s best moment is not the Sons of the Pioneers performance of “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen” but the reactions of Wayne and O’Hara as it is performed, and the wordless communication they share in the moment.

10. Donovan’s Reef (1963)

The only comedy among the major Ford-Wayne collaborations, Donovan’s Reef was a just-for-fun project about a World War II vet whose tropical island retirement is upended by a young American girl searching for her father. Nothing deep, just Kauai in Technicolor, old friends and pretty ladies, and a great saloon brawl. The loose tone on the set was witnessed by one reporter who asked Wayne where the bar fight was in the script. Replied Duke, “What script?”

11. The Wings of Eagles (1957)

Ford pays tribute to his old friend Frank W. “Spig” Wead, a decorated World War I Navy aviator who became a screenwriter after an accident left him paralyzed. Wayne is outstanding here in what is not always a heroic portrayal: Wead is a hard man to like, and in his own way as obsessive as The Searchers’ Ethan Edwards. Ford negotiates several challenging tonal shifts, mixing dark domestic scenes with Ward Bond’s blustery sendup of Ford in his gruff portrayal of Hollywood director “John Dodge.”

12. The Horse Soldiers (1959)

While not classified with Ford’s cavalry trilogy, The Horse Soldiers shares the same esprit de corps in its portrayal of a Union cavalry regiment battling its way through 600 miles of Confederate territory. As with many of the Ford classics (Stagecoach, The Searchers), it’s about getting from one place to another and is more about the journey than the destination. On-screen, the film belongs as much to William Holden, who plays an Army surgeon, as to Wayne, once again at the head of the charge as Col. John Marlowe. It’s an intriguing pairing, but Holden is no Maureen O’Hara.

13. How the West Was Won (1962)

Ford directed the Civil War chapter of this historical epic, set during and just after the bloody battle at Shiloh. Wayne plays Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, whose summit with Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (Harry Morgan) is interrupted by an assassination attempt. While it’s still fun to play spot-the-star among the film’s gargantuan cast, How the West Was Won never views well at home; even on a big-screen television, the massive Cinerama image has to be squeezed down to the relative dimensions of a business envelope to fit into the frame. It’s still worth seeing, but the Ford-Wayne contribution comprises only one part of the whole, and it’s not even the best part.

14. The Long Voyage Home (1940)

Ford took his stock company off the range and onto the high seas for this adaptation of four Eugene O’Neill stories about the wartime merchant marine. Slow and talky, The Long Voyage Home is distinguished only by the light and shadow artistry of cinematographer Gregg Toland. Wayne, looking younger than he did in his star-making Stagecoach performance the previous year, is a man of few words here as Ole, a Swedish farmhand turned shipmate. “From my point of view,” Wayne once quipped, “The Long Voyage Home could have been titled Wayne’s Long Struggle With a Swedish Accent.”

From the October 2014 issue.