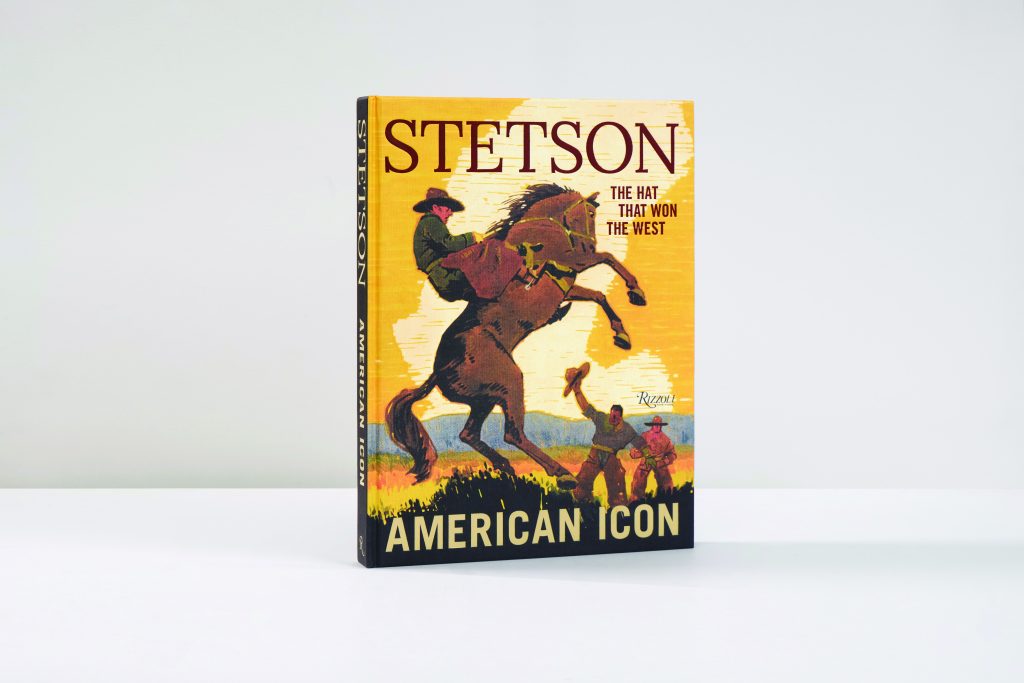

America’s legendary hat brand marks its 160th anniversary with a handsome tome chronicling every angle of Stetson’s heady rise — from humble Philly roots to becoming the chosen crown of the American West and beyond.

If the West could be distilled into a single iconic, historic, symbolic, heroic garment, it would of course assume the shape of a hat — but not just any old brimmed and banded number. It would be a Stetson.

Inspired during a Rocky Mountain expedition and launched in 1865 in a one-room Philadelphia workshop by an indefatigable visionary with a knack for scaling brutal personal setbacks (like any Western-leaning narrative worth its salt), the John B. Stetson company may not have invented the cowboy hat, but it might as well have. Credited for popularizing America’s most celebrated hat and branding itself as the gold standard for fedoras, flat brims, and other classic styles over generations, Stetson would become interchangeable with the word “hat” in an era when no gent would rightfully be seen in public without donning a proper one.

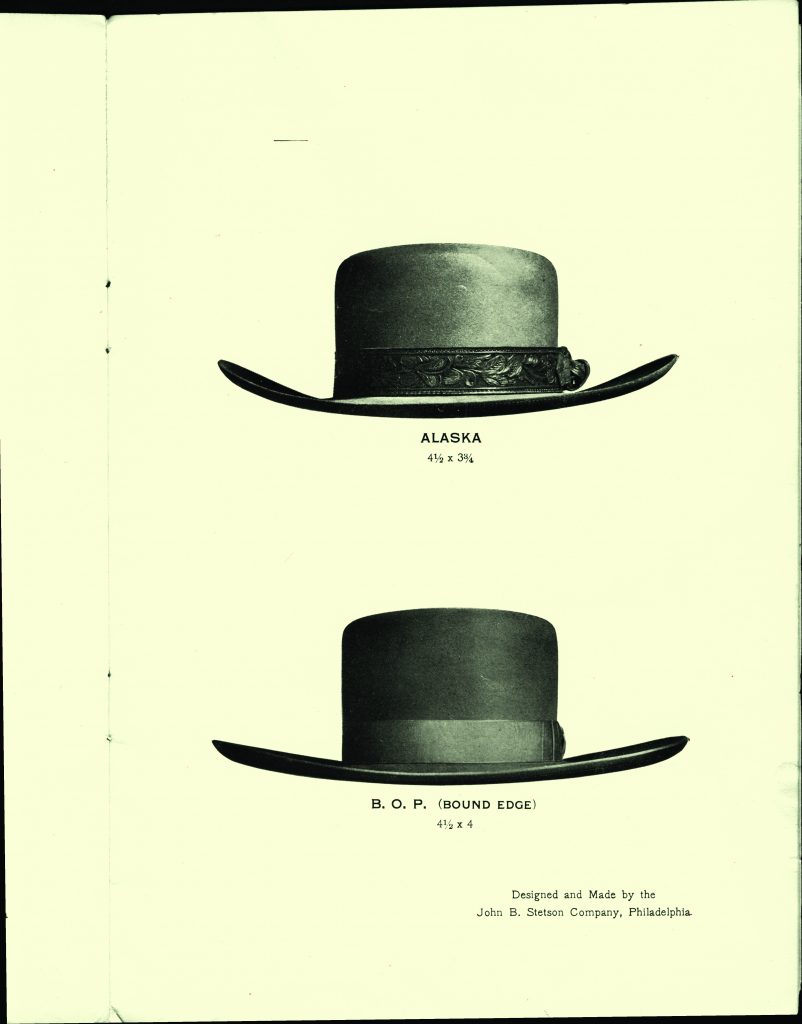

The company’s first hit release, the Boss of the Plains — a handmade, four-inch open-crowned and brimmed fur-felt workhorse modeled after hats worn by Mexican vaqueros — “was so sought after,” notes Stetson: American Icon, a new, heavy-duty hardback published by Rizzoli to celebrate the brand’s 160th anniversary, that some orders even arrived with a bit of cash thrown in to incentivize faster delivery. Within 20 years, Stetson would become the world’s largest hat company, eclipsing generations of European dominance while taking home the grand prize for quality and craftsmanship at the 1900 Paris Exposition. Paris judges declared the Stetson “the acme of perfection.”

Covering America’s headiest hat story requires some heft — and Stetson: American Icon provides plenty. Bound inside this thick and thorough 10 x 13-inch volume, readers will find a vivid, entertaining, informative tribute to “The Hat That Won the West.” It may even get you seriously thinking about your own next Stetson. If it’s your first, you’ll be joining quite a club.

From fashion to politics, movies to the military, ranches to the open roads, city streets to the jet-setting skies, galleries to the gridiron, and all manner of musical styles from country and pop to jazz, Stetson has touched virtually every facet of American culture. The book captures it all — in a visual feast filled with full-color pages showcasing style-makers of all stripes in their Stetsons. Thoughtful essays about Stetson history, production, and aesthetics explore the hat from varied angles alongside gorgeous archival imagery.

There’s a short, sweet bit by Lyle Lovett introducing the chapter “Stetson in Song,” a compilation of Saturday Evening Post cover illustrations featuring famous Stetson wearers, and a kaleidoscope of ad campaigns through the decades. There’s even a section dedicated to “Stetson Stories” — proving that the right hat can inspire many a memorable moment.

But back to the book’s countless images. If you’ve forgotten just how many famous folks rocked a Stetson between the Tom Mix and Post Malone eras, here’s your memory lane. The photo pantheon in these pages includes, in no particular order and among many others, Louis Armstrong, Lady Gaga, Lyndon Johnson, Benedict Cumberbatch, Steve McQueen, Georgia O’Keeffe, Hank Williams, Margot Robbie, Harry Truman, Beyoncé, Burt Reynolds, Clarence Gatemouth Brown, Ronald Reagan, Willie Nelson, Roy Rogers, James Dean, and a nostalgia-inducing pinup from a 1987 ad campaign with John Dutton, Randy White, and Ed “Too Tall” Jones posing in Dallas Cowboys uniforms with their Stetsons above the slogan “Cowboys Wear Stetsons.”

Covering 160 years of one of America’s most influential and photogenic heritage brands is a big task — one this big book handles handily. Offering an evocative look at the name that has defined the West more than any other crowning achievement in its field, this coffee table classic should not be kept under your Stetson.

Exclusive Excerpt: “An American Adventure Story” by Douglas Brinkley

A young pugilist from Oklahoma arrived in Butte, Montana, in 1913, looking for a fight — literally. He was a boxer, but one without an address, telling the town’s newspaper that should anyone want to arrange a bout, “You can find me on the street any time with a big white Stetson hat on.” That boast only made the editor laugh.

“So, would-be managers,” the editor chided, “keep an eye out for a big white Stetson hat. There are only several thousand worn here every day.”

By 1913, the John B. Stetson Company of Philadelphia had been making cowboy hats for almost fifty years; the very name “Stetson” had become a noun in popular use to mean “cowboy hat.” Beyond its utilitarian reputation for protecting the wearer from the elements, the Stetson had been embraced as a kind of badge that bonded Westerners together, whether they worked on ranches or not. Broad and bold, unapologetic and impossible to ignore, the Stetson cowboy hat became the preeminent symbol of the American West. It still is: To see a Stetson is to think of the horse- and cattle-country of our western states.

And yet, the Stetson is (and was) loved just as much by people in New York City (and all over the world) as a symbol of something just as powerful: the romantic dream of the Wild West as promoted by the likes of Buffalo Bill. For them, the Stetson carried a breeze of freedom wherever it was seen. Rakish and dependable, it was more than a good-looking hat — it beheld a life without petty constraints. Ironically, by the early 1900s — when the cowboy president, Theodore Roosevelt, was in the White House — a great many Westerners were also starting to feel the urban binds of modern society. As declared at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, the American frontier was closing, if not already closed, with little wilderness left to explore. The coming of the Ford Model T changed the way of life, replacing the horse as the preferred mode of transportation. Yet Westerners still wore their Stetsons — whether made from felt, straw, leather, or other materials — more determined than ever to honor the old bonds.

That the Stetson Company — born in the East but inspired by the spirit of the West — originated the cowboy hat and then popularized it to the iconic symbol is one of the soaring successes of American business history. Ever since, Stetson has prevailed against whatever the market has thrown at it, and through it all, the company managed to stay true to its iconoclastic Western identity. Most hat companies, in fact, have vanished. Stetson has remained indomitable for more than 150 years, through bleak times and booms, primarily for two reasons: its high quality and an inextricable place in Western fashion. Each obstacle over the years has been stubbornly met with a single goal: shielding the beloved hat from compromise. For that reason, the company occupies a prominent place in the history of the nation. Since the very start, Stetsons have been teaching us something about ourselves.

For more than a century, Stetsons were made in Philadelphia by a man from New Jersey. In a sense, though, the company started far out West, at the time of the Civil War. John B. Stetson, born in 1830, was in poor physical condition as a young man, receiving a diagnosis of tuberculosis that would ultimately keep him from military service. In the late 1850s, he left his home in New Jersey, in favor of the dry air of the West, settling first in Missouri, where he learned to make bricks. It was a perfect match for a man with very little capital, but a true gift for manufacturing. The elements needed for bricks were free, or nearly so, in St. Joseph: clay, water, straw, sunlight, and wood for fuel. In the span of about eighteen months, Stetson moved from laborer to manager to part owner to sole owner of a brickyard on the banks of the Missouri River. In his company’s first season, it produced a whopping half-million bricks that were laid out along the riverbank to dry. Unfortunately, the entire inventory was washed away in a flood. Stetson lost money but not a bit of his ambition; in fact, the experience solidified his intention to own another business. First, though, he wanted to see more of the West, including the Rockies, and it was there that he recognized his true calling.

The family legend was recounted by his son, John Jr., during a 1938 interview:

“My father was very frail as a young man and went West to regain his health. He joined some other young men who were walking to Pikes Peak [in Colorado], amusing his friends by making a hat out of felt, using the fur of the rabbits, beavers, and skunks they killed along the trail.

The hat was big and picturesque. It protected him from the wind and rain, as well as from the scorching sun. Besides, it attracted attention. A bullwhacker on horseback, gaily seated on a silver-mounted saddle from Mexico, looked upon this hat with envious eyes, and then offered my father a five-dollar gold piece for it. This was the first genuine Stetson hat made and sold.”

Stetson had learned to “build” hats — the verb that hatters prefer, rather than “make” — from his father, Stephen, an independent hatter of intermittent success in New Jersey. No doubt aided by the built-in help of his wife and twelve children, Stephen ultimately gained a good reputation and retired after amassing a fortune of $50,000 — which he almost immediately lost in bad investments. The family was in some disarray by the time John returned home during the last year of the Civil War, but he was in better health; and, equally important, he had firmly decided to seek his own fortune in the family trade.

After an initial hat-making partnership failed in New Jersey, he borrowed sixty dollars from his sister, moved to Philadelphia, and started the John B. Stetson Company, at first merely cleaning and repairing hats.

The industry was undergoing the same transition as many others in the mid-1800s, when the role of local or home-based businesses was ending in favor of centralization in factories. At the time John Stetson entered the fray, the largest hat company in the nation was Knox, located in New York City; it employed three hundred people. Four dozen of his other rivals were clustered in Danbury, Connecticut. In addition, Stetson faced competition from France, with its expertise in making soft wool hats as well as fine silk ones. England had recently taken the hat world by storm by introducing something entirely new: the derby, a so-called stiff hat that was fully rounded — unlike top hats, like the ones favored by Abraham Lincoln.

Almost immediately, Stetson made his mark, perfecting his all-season western hat and introducing it as his first product: The Boss of the Plains. Aside from the originality of the design (which was inspired by that first hat he crafted in Pikes Peak), the new hat was revolutionary because it had a name — a flashy, romantic, storytelling identifier different from the categoric “Derby–formal no. 3,” for example, that other hatmakers used. This was a Stetson innovation: his hats would have an identity. They would be a brand.

As a design, the Boss was the very first cowboy hat. It had a generous crown and a four-inch brim, the latter being regarded by other hatters as a remarkable feat in shaping. The felt, derived from pulverized beaver fur, was effectively waterproof, holding its shape even after it was drenched. The Boss had antecedents, of course — the sombrero found in Mexico and South America, the plantation hat used in the South, and the wide-brimmed cavalry hats worn during the Civil War.

Stetson’s hat was more durable than its precursors, though, and more distinctive, starting with its outsize brim and ribbon-bound edge. Sometimes small innovations can change a familiar object entirely, and so John Stetson deserves credit as a designer. Purely practical throughout, the hat nonetheless had a bold stance and, even in that early iteration, it complemented buckskin and dungarees. More styles would follow: bigger or more compact, rounder or squared off in the crown. The model evolved yet was still instantly recognizable as a Stetson. The name built a reputation with the passing years, in part because well-crafted felt lasts a long time, and Stetsons often ended up looking even better with age.

The Boss model sold well from the start, but the leap from repair to actual manufacturing brought a searing test of Stetson’s determination: his suppliers insisted he pay cash on delivery for the materials he needed, but he couldn’t pay them until he actually sold the hats. The business was doomed to stall or else grow so glacially that it wouldn’t become viable for decades. Stetson pinched every penny, trying to narrow the gap between obtaining supplies and selling finished hats.

Then something occurred that he may well have considered an act of God — the impulse of an Irish fur dealer who trusted Stetson enough to give him ten dollars’ worth of revolving credit. It wasn’t much, but it was enough to give Stetson a future in business.

Stetson was creative in marketing his hat to retailers in the West: he would send samples to far-flung stores across the country, then have the home office press them relentlessly for orders. Once the outline of a retail network was thus created in a region, the Stetson Company built a sales force around it, pressing field salesmen hard to push the hats into stores — and, importantly, into local newspapers. They succeeded on both counts, and there was typically a small article in the paper whenever a shop began to carry the Stetson. Moreover, the word “celebrated” was almost invariably attached, as in “the celebrated Stetson hat.”

The strategy worked, and by the mid-1880s, ads throughout the western states set the brand apart. Headlines like one in a Billings, Montana, newspaper in 1885 proclaimed:

“COWBOYS: This is your chance to get a square deal ... Stetson hats and riding boots.”

Other hats, if they were carried, were just hats. A Stetson was a Stetson.

Stetson: American Icon, published by Rizzoli, released September 30, 2025, in celebration of the brand’s 160th anniversary: $100, 320 pages. Order online at rizzolibookstore.com. Excerpt with permission of the publisher.

PHOTOGRAPHY (All images): Courtesy Stetson.

From our November/December 2025 issue.