A magical guitar — beloved by Jeff Bridges, James McMurtry, and a certain musical Montana cowboy and Montana Blackfeet Indian — tells the secrets of an irreplaceable forest and just might hold the key to reconciliation and survival.

In the farthest, most northwestern corner of Montana — the Yaak Valley, hard against the border with British Columbia — stands a mysterious old forest, where previous notions about a great many things are turned upside down. In this enchanted forest one commonly finds two trees, long thought to be enemies of one another — sun-loving larch, for instance, and shade-dependent cedar — growing shoulder to shoulder, not merely tolerating one another, but somehow prospering alongside each other.

In the incendiary West, the Yaak — Montana’s lowest valley, and the wettest — is the last place that fire will come. It’s a place to make a stand. A Noah’s ark of diversity — nothing’s gone extinct in the Yaak, yet, since the last ice age — and a Fort Knox of carbon.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Rick Bass

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Rick Bass

The Yaak is a land of strange superlatives: The old forest has never been logged, and there is no evidence that it has ever burned. Fully 25 percent of all the species listed as “sensitive” by the State of Montana are found in this one national forest alone, the Kootenai National Forest. It’s also the site of a much-contested “Black Ram” timber sale that would log some 60 million board feet of mature and old trees to be shipped to Idaho. When local residents with the Yaak Valley Forest Council took the forest supervisor for a hike into the old forest to see what his staff had planned, he shrugged and said the decision was not his — that it was coming from Washington. The sale was advertised as being necessary for “fuels reduction.”

This was a puzzlement to locals: There isn’t a human structure within a hundred square miles. The Forest Service had already clearcut to the edge of the proposed logging units; water streamed out of the forest, and the giants at its edges were beginning to tip over, no longer supported by their cohorts. Many of the suddenly felled were enormous spruce; and volunteers seeking to defend the old forest dreamed up a new way to advocate for them. Because the Black Ram forest has an incredible creation story. So, too, does the guitar that tells it.

One wet late-spring day, with a photographer friend, I went in with a wheelbarrow and cut out a length of wood from one of the fallen ancient spruce trees. We took a piece of the tight-grained wood — about the size of a whale vertebrae, I like to imagine — to Kevin Kopp, a master luthier who made the first Black Ram guitar. Actor and musician Jeff Bridges heard the guitar play at a small concert in Whitefish and leapt into the project, commissioning six more Black Ram craft guitars to be built through his partnership with Breedlove Guitars and their “All in This Together” campaign, wherein guitars are made only with wood sourced sustainably in the United States. (Founder-owner Tom Bedell says that such integrity adds only a couple of dollars to the price of a finished guitar and that the strength is superior.)

The guitar weighs 4 pounds and 6 ounces and is constructed of the light from above. Much is being placed upon her. The tree she came from was a seed the size of the head of a sewing pin, roughly 315 years ago. She has come a long way and the musicians who are drawn to the story understand the import of her story: to save her forest first, and then to designate that the public land north of the Yaak River and south of Canada be managed as the nation’s first Climate Refuge.

What is a Climate Refuge? It’s a place dedicated to storing the maximum amount of above-ground carbon in the long-term safekeeping of old and mature forests, and a place for increased focus of scientific and artistic inquiry into the effects of climate change on sensitive species, including our own.

As proposed by the reports of various climate scientists and the on-the-ground work of the Yaak Valley Forest Council, the region north of the Yaak River and south of Canada could be a pilot project that would be comanaged by not just the Department of Agriculture’s U.S. Forest Service, as it currently is, but also by the Department of Interior’s U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, which provides greater focus and energy to recovering the Yaak’s grizzly population — the most imperiled in North America. The Climate Refuge vision includes a third party in management: a tribal nonprofit such as the Confederated Salish and Kootenai.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of R. A. Beattie

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of R. A. Beattie

To that end, an informal coalition has been guiding artists and scientists into the old forest. Scientists have begun measuring the differences in the rich effervescent mycorrhizal activity in the ancient forest and comparing it to the absence of that activity in clearcut soils. It turns out that old forests are really good at protecting themselves, delivering nutrients to those trees in the forest that need them most, and communicating with one another, silently — or rather, with a method of transfer of information we cannot hear. How rich is the old forest at Black Ram? A single tablespoon of soil can hold miles of hyphae — translucent fibers attached to mycorrhizae like the cilia of our inner ears. Listening, communicating, to a world just beneath our feet.

And artists are in the fight, too. Many are pitching in on the grand experiment to defend a grand old forest, and from that, all old-growth. Clyde Aspevig and Monte Dolack have made large paintings of Black Ram. Beth Ann Fennelly, Chris Dombrowski, and other poets have walked in the old forest and come out with poems. U.S. poet laureate Ada Limón has also visited the forest and re-emerged with two poems about it.

But the message might be most potent in music. Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter Maggie Rogers; Texas folk rocker James McMurtry; Pearl Jam’s Jeff Ament; Bonnie Raitt’s guitar prodigy, Roy Rogers — slowly, chord by chord, musicians around the around the world are listening to the story of the Black Ram guitar and rising to the defense of her forest and, having made that first stand, to a defense of all old forests.

Could a guitar be the right choice — the best way to defend the forest? Only time will tell.

A small group of us gather on a Tuesday afternoon in early March at Rob and Bonni Quist’s Starlight Theater — a small recording studio — on the ancestral lands of the Salish and Kootenai to hear two seemingly unlikely allies play the guitar in defense of the forest: one a Montana cowboy and the other a Montana Blackfeet Indian.

To call Jack Gladstone a Blackfeet warrior — the term itself an oxymoron — is not inaccurate. At 6 feet 3 inches he attended the University of Washington on a football scholarship, where he played three years, including a Rose Bowl Championship season in 1978. He had started playing guitar and writing songs, however, and realized after his junior year that he’d prefer to make a living with his hands and voice as a musician, rather than on the gridiron. As he turned away from the bloodsport and toward reconciliation, he did not fully know what he was moving toward.

Jack is candid about the potential for bitterness that any Indigenous person can feel, having had their homeland forcibly taken from them. One could understand how he might not be inclined to be particularly friendly toward the festive cowboy with the fancy bandana, to crib a phrase from Tom McGuane.

But life is too sacred and short to spend it inhabiting that bitterness. He was bound for Rob, and Rob was bound for him. And to these two now-aging musicians, the guitar’s story from the old forest — with its lessons of diversity and resiliency — is cause for excitement and collaboration, so much so that they are pouring body and soul into it and possessing once more, it seems to me, the energy, passion, and imagination of the younger men they once were.

(Left to right) Jack Gladstone, Rick Bass, Corwin Clairmont, Rob Quist (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Bonnie Willows Quist).

(Left to right) Jack Gladstone, Rick Bass, Corwin Clairmont, Rob Quist (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Bonnie Willows Quist).

If Jack Gladstone’s life has been quintessentially Indigenous, and American, Rob Quist’s has been quintessentially Montanan, and also American. He was born and raised on eastern Montana’s “Hi-Line,” near the Canadian border — wheat and cattle country — attuned to the cycle of four seasons that still attends to rural life in special places like Montana.

His first instrument was a banjo, purchased because at $40, it was the cheapest available. Then as now he lived in a tumultuous time in American history: In the 1970s era of rock and roll, he became a member of the most popular band in Montana, the Mission Mountain Wood Band, which attracted cult followers not unlike those of the Grateful Dead. After a tragic plane crash killed several band members, Rob re-formed the survivors to become the Montana Band, and later, Rob Quist and the Great Northern. Now it’s just Rob Quist.

Rob has walked in the forest at Black Ram and has visited the carcass of the fallen giant from which the first guitar was made. He has sat on the log and played a song he wrote for the guitar, and for the forest, called “See the Forest for the Trees.”

Jack refers to Rob as a big brother and mentor. It was nothing short of a little miracle that led Jack and Rob to bump into each other. As Montana musicians, they knew of each other but had never had occasion to be in each other’s company until they found themselves double-booked for a gig in East Glacier. Rather than splitting the available time and playing separately, they played together and had a great time. And that night — both beleaguered from the road — they sat beneath the thundering power of the Swiftcurrent River coming over Red Rock Falls, working out all the knots in their necks and carrying all those tensions downstream. The idea for their Western Harmony tour was launched, and they subsequently toured all around the country, the cowboy and the Indian, reminding people how the differences between any two humans can become an opportunity for counterpoint and harmony.

Bridges teaching some guitar to author Rick Bass (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Bonnie Willows Quist).

Bridges teaching some guitar to author Rick Bass (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Bonnie Willows Quist).

The highlight occurred at Monticello, where they played a concert in Thomas Jefferson’s library — the first time that had ever happened. The books sitting silent on the shelves had been the seedbed for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and for the nation we are now, in Montana and the West — not the nation that predated that exploration, the one that had existed here for 14,000 years or longer, the one that still exists today if you know where to look. The Jeffersonian conversation — a cross-country expedition seeking passage, scientific discoveries, and cultural knowledge — is still going. Jack and Rob are doing their parts to keep the conversation going, adding a personal perspective of the long view of this land pre- and post-contact, cowboy and Native American. Jack estimates that from touring, he’s traveled 2 million miles, with much of that distance in Montana. Rob, 10 years his elder, estimates he’s traveled 3 million.

Rob and Jack are Montana’s story-smiths; the Black Ram guitar is a storykeeper. Jack tells of the buffalo Charlie Russell portrayed in one of his last paintings, a commission for the tony wealth of the Montana Club. One carpetbagger or another from back East came up and critiqued the master, saying he thought the buffalo Russell was putting the finishing touches on “needed more work.” Russell stepped back and looked at his patron. “It’s the best one I’ve ever painted,” he said, and that was that. Jack reminds us it was also Russell who said of Montana, “Guard, protect, and cherish your homeland. For there is no afterlife for a place that started out as Heaven.” (It cannot be improved.)

Another of Jack’s mentors was Joseph Epes Brown, known for a lifetime devoted to learning about Native American traditions and then for teaching about them as the first professor of American Indian Religious Studies, part of that time in Montana. His influential book The Sacred Pipe detailed his discussions with Lakota spiritual leader Black Elk, with whom he lived for a year, about his people’s religious rites.

Jack takes the spiritual teachings to heart. For him, so much of our treatment of the natural world, and each other, and self, comes down to what he considers the three tenets of Indigenous teachings: rhythm, balance, harmony. He’s talking about life, but he could be talking about a stand of old-growth trees or music or, indeed, the guitar.

The Black Ram guitar’s sound is sweet and resonant, big and bright. Musicians who play her comment that she sounds like an older, richer guitar, which actually makes sense: She was 315 years a tree, taking in sound and song, and now has been barely but one year a guitar.

Kevin Kopp, the luthier who built the first Black Ram guitar, described the mother-of-pearl inlay as “the hardest I’ve ever done.” And the most beautiful (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Bonnie Willows Quist).

The thing I love best about the old forest — beyond walking across the incredible scientific treasure house — is how, when you first step into it, there seems to be disorder everywhere. Fractured snags seeming frozen in time, having just exploded. Trees leaning slowly down toward the dark, rich earth below, an unseen universe of decaying organic matter and soil teeming with life even as it decomposes. The natural litter of the forest floor sprouting new growth, seeking sun. And I love the sounds: the drumming of pileated woodpeckers hammering on the giant standing dead, and, in a breeze, the way one leaning snag might slide ever so slightly back and forth against one of its standing green comrades, making a sound like that of a bow being drawn across a cello or a violin.

In the old forest, it’s possible to reexamine your relationship with yourself — and, in the right mood, your relationship with time, with life itself. At first all the trees looming around you might seem like an imprisonment, or entrapment — that there is nowhere to go. But then you begin to think other thoughts. You can’t hear the music of the light pouring down from above, but you can see it. And whenever you stop, you realize: The old forest is not still. The smallest breeze down below translates into great movement, great song, far above.

All around you, and beneath you, and up high above you, the trees are singing. Once initiated, soundwaves never stop vibrating but live forever, trembling, even if ever so slightly, in the wood in which they have taken residence. Into which they have been absorbed. You listen, hearing without hearing, and then, after a while, you get up and start walking again.

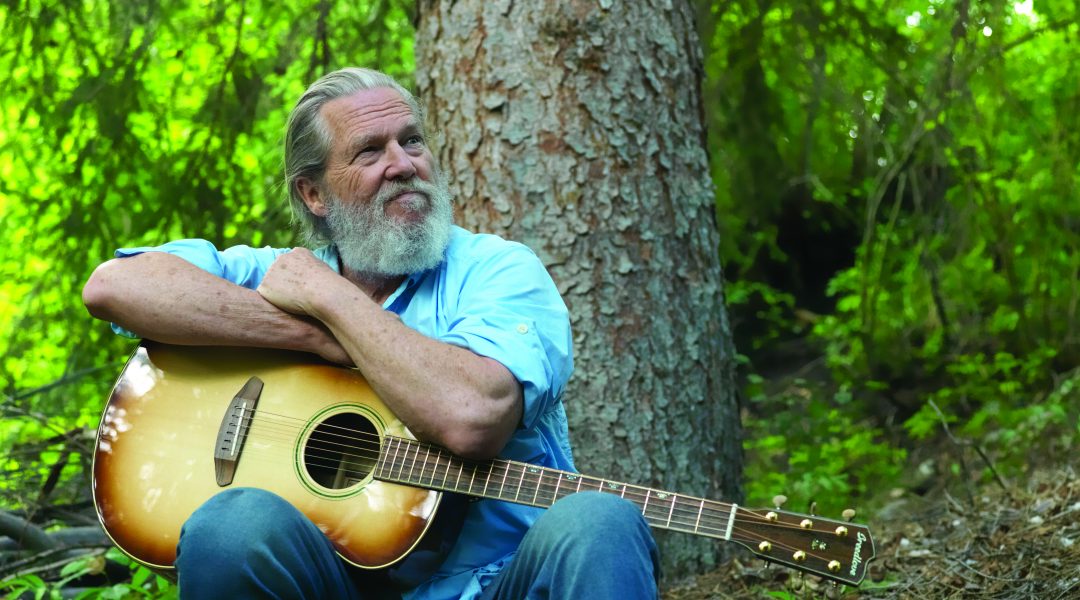

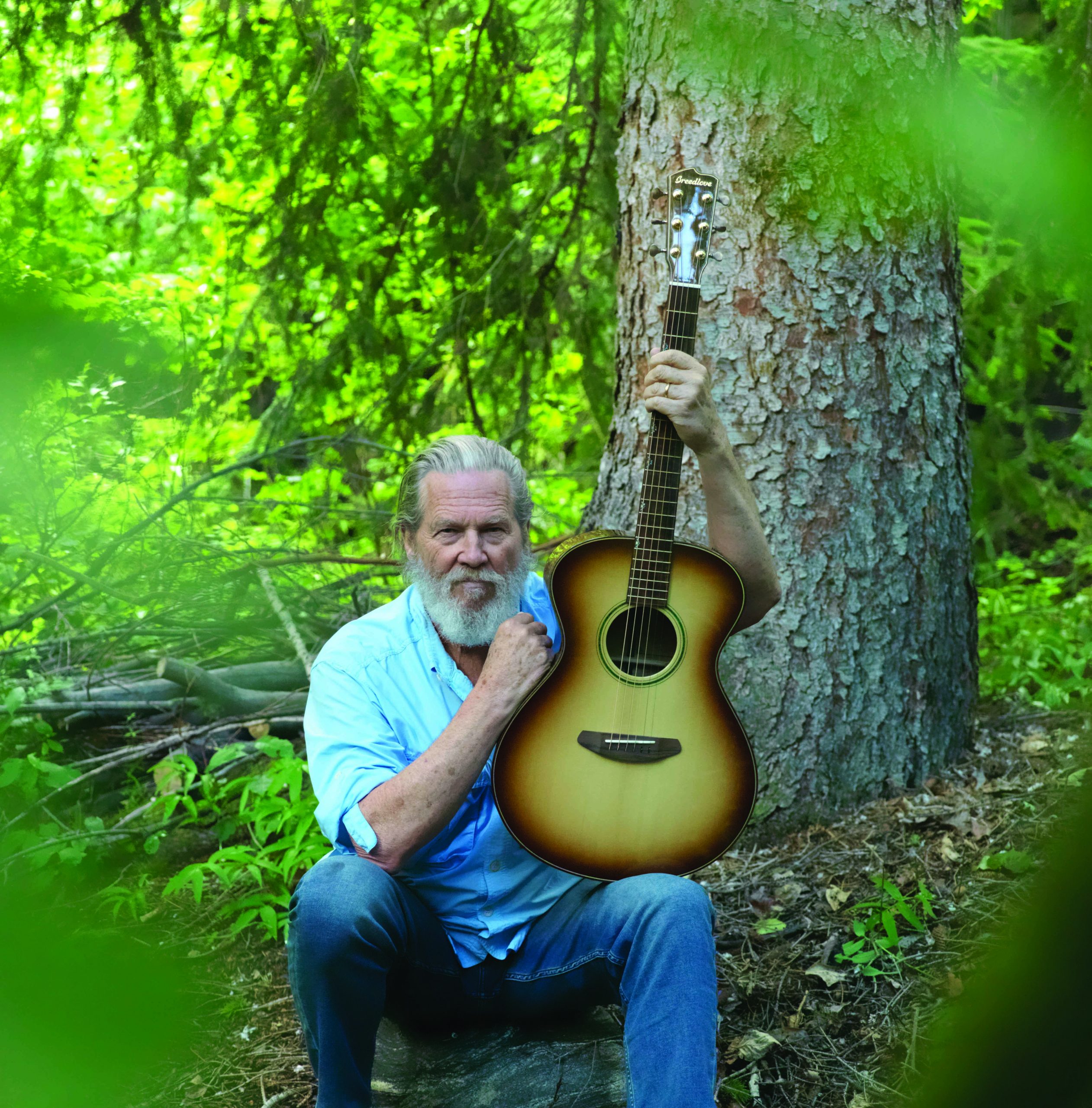

Jeff Bridges, a longtime Montana resident (pictured here with the Breedlove guitar), is one of the celebrities who have taken a keen interest in the endangered Black Ram forest and the special guitars made from a tree felled in it (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of R. A. Beattie).

Jeff Bridges, a longtime Montana resident (pictured here with the Breedlove guitar), is one of the celebrities who have taken a keen interest in the endangered Black Ram forest and the special guitars made from a tree felled in it (PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of R. A. Beattie).

“The old forests like Black Ram are our teachers,” Corwin Clairmont says. “Ancient trees tell us how we should live.”

Clairmont is a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai cultural committee and is also on the board of Montana Arts Council. He and Linda King, a prizewinning beadwork artist, are part of the tiny gathering at the Starlight the night Jack and Rob play the Black Ram guitar and sing the songs of reconciliation, bathing us in balance, rhythm, and harmony.

As a host to the ancestral lands, Corwin speaks to us after the music has stopped. There are ceremonies, he says, that his people used to do in the area proposed now as the Black Ram Climate Refuge. “We don’t talk about them,” he explains, and stays mum on the subject, but he does allow a description of them as “special ceremonies that take us back in time.” And art, he says, is like the old forest. “Art is how we nurture our spirits. Art helps us keep in touch with the importance of life itself. Through the arts and through these songs, we have the ability to express our spirits.”

The forests at Black Ram, Corwin says, “know what they have to do to survive. They do it really well. And we’re part of the natural order, just like that tree.” The forest at Black Ram, he reminds us, “doesn’t have to go anywhere to provide nourishment. These musicians we heard today — the Creator has put them in our path. And we are all the younger brothers and sisters of the natural world. We are all children of God.”

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Bonnie Willows Quist

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of Bonnie Willows Quist

In olden times, trees were said to be the babysitters for children.

I’m aware there’s a clock on the wall at the back of the theater, but I refuse to look at it. I will myself to look past the clock, and not into the past, but into the future.

The dark side of our nation’s birth — genocide and slavery — must never be forgotten. But Jack reminds us that before the bad, there was good. He reiterates the three tenets of Indigenous spirituality — balance, rhythm, and harmony — in all matters.

And if those principles could be writ large at this precarious time on our precious planet, why not a Climate Refuge, the first in a living, breathing halo of green, a Curtain of Green, encircling a tilting, burning world? Why not the Confederated Salish and Kootenai, and the Blackfeet, resuming their timeless rituals, comanaging the old forests and moving through them with drums and flutes made of wood from the forest, performing ceremonies of healing, continuity, and meaning? Why not the sound of a magical guitar that plays the songs we hold most dear — as well as teaching us new songs, helping us regain old notions of community and balance, rhythm, and harmony?

There at the Starlight, hearing the harmony coming from the enchanted forest guitar, from Indigenous men and women gathered there speaking of brotherhood and sisterhood — not just with forests and bears but, hardest of all, with each other as humans — it feels to me like one tiny seed has been planted in the farthest corner of Montana.

And I think of all those billions of miles of underground mycelia, communicating among every living tree: the trees breathing, singing, reaching for the sun.

From our July 2025 issue.

HEADER IMAGE: Courtesy of R. A. Beattie