Stop in during March’s Western Art Week at Kid Russell’s place to see the newly unveiled reinterpretation of his home and studio in Great Falls, Montana.

Update: The C.M. Russell Museum's sale and exhibition The Russell has been moved online. For more details, click here.

A poker game fueled by whiskey explodes in gunfire outside a frontier saloon. A wounded cowboy falls from his horse, his foot hung up in a stirrup, while his two buddies open fire on the gambler who shot him. The gambler is hit as well, falling back against the rough wall of the saloon, as a smoking six-shooter dangles from his hand. Panicked horses scramble at the shooting, desperate to get away. It’s all captured in oil on canvas in In Without Knocking, another action-packed painting of the Old West, from the brush of the legendary cowboy artist Charlie Russell. Today, you can stand exactly where that painting was created, in Russell’s restored historic log cabin studio in Great Falls, Montana.

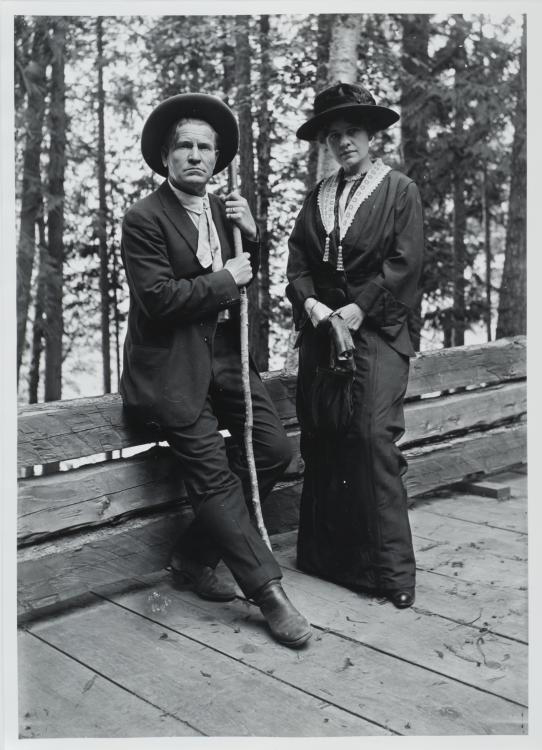

“If you’ve ever seen a photo of Charlie’s studio, with Charlie standing there, you’ll feel like you’re walking into one of those photographs,” says Christina Horton of the C.M. Russell Museum.

The museum recently completed a $1 million renovation and reinterpretation of Russell’s studio and the home just steps away that he shared with his wife, Nancy. Step into both and you’re stepping back into the world they lived in more than a century ago.

Russell’s studio was filled with mementos and artifacts from the world he had lived in — as both a friend of the Indian and a working cowboy — on the vast open ranges of Montana during the final years of the Old West. Beaded gloves, Indian leggings, and a war shirt are among the items hanging from the cabin walls. In a corner stands a backrest like one you’d have seen in a tepee. A bearskin coat hangs on a stand next to an easel holding an unfinished painting of Native Americans on a hilltop using a mirror to flash signals, a masterpiece that would be known as The Signal Glass. A paintbrush and antique tubes of paint rest on a nearby palette. You can pick up and read a letter to Russell’s only protégé, Joe De Yong, giving tips on how to paint a horse. Close by is a clay model of a horse, like one Russell could fashion with his hands in an instant.

It all looks as if the artist has just stepped out for a moment — except that everything you see is a historic re-creation, identical to the real items that were once in this room. “Some are sad it’s not the real stuff, but we tell them [displaying the originals] wasn’t sustainable,” Horton says.

For years, Charlie’s real memorabilia was on display in the studio, but visitors could only see the century-old items from a distance, in a small viewing area, behind a wall of Plexiglas. “It wasn’t a very interactive or immersive experience,” Horton says. “Some of the artifacts were so fragile they broke when we moved them. They wouldn’t have lasted 10 years, let alone 100.”

While the items might no longer be Russell’s originals, the studio certainly feels authentic. Instead of peering through glass, you can wander around the big room where the master created his art and took time to visit with his old cowboy buddies, known as “The Bunch.” Russell’s friends are often seen in his paintings, men he came to know during his years riding the open range. John Matheson, an old freight-wagon teamster known to be one of Nancy’s least-favorite people, was one. According to Russell biographer John Taliaferro, Matheson, who was never fully housebroken and much preferred relieving himself in the yard instead of the indoor bathroom at the Russell home, timed his visits to make sure she wasn’t around.

As a boy in St. Louis, Russell was so obsessed with the West, his parents sent him to Montana in 1880 when he turned 16 to get it out of his system. He never moved back. Before long, Kid Russell, as he was known, was working for the big cattle outfits, wrangling horses. He would cowboy for more than 10 years, experiencing firsthand a life that would soon vanish forever. All the while, he was sketching, drawing, and molding clay, both remembering and imagining the dramatic Western scenes he would later re-create in oil, watercolor, and bronze.

We’d probably never have known of Charlie had it not been for Nancy. Before she came along, the artist often gave his work away or traded it for drinks. Everything changed when he met Nancy Cooper in 1895. Married the following year, the 18-year-old Mrs. Russell became Charlie’s business manager, negotiating the exhibits, commissions, and sales of his work that brought Russell fame and an income worthy of his talent.

Today, when you step inside the home the couple built in 1900, a re-creation of Nancy’s desk is the first thing you see — and hear. A motion detector triggers a video that plays on the desk blotter, where you can hear an actress portraying Nancy chatting on the phone with a customer. “Did you get the sketch?” she asks. “Did you like it?”

While the studio was clearly Charlie’s domain, Nancy was in charge of the house. Newly refurbished and reimagined, the house is furnished and decorated to look as it once did. “We took it back to as close as we could get it to when Charlie and Nancy lived there,” Horton says.

Horton admits there are not many photos of the Russells’ home life, but meticulous researchers did track down and re-create the home’s original red-flowered wallpaper. And you can still see marks where curtains hung to block off a downstairs living room, a corner of which served as Russell’s studio from 1900 until the cabin studio was built in 1903. The room included an outside door through which “The Bunch” could slip in for a visit without disturbing Nancy.

History tells us some of those guys clearly preferred their old cowboy buddy to the domesticated version of Charlie. But the artist was a happily married man. His talent focused, managed, and likely inspired by his true love, Russell was incredibly prolific. He created approximately 4,000 works of art, re-creating the unspoiled Old West of cowboys, Indians, and wildlife that he had known firsthand and missed like a long-lost love.

“Russell really created the scenes that we remember today as the culture of the American West,” says former museum executive director Michael Duchemin. “The West that we think about when we think about the West is the West of Charlie Russell.”

Thanks to him, and the guiding love of Nancy, we can still visit that world of buffalo hunts, wagon trains, and the In Without Knocking — and the home and studio where the paintbrush of the Cowboy Artist brought it all back to life.

Visit the C.M. Russell Museum online at cmrussell.org.

Photography: Courtesy Amon Carter Museum of American Art, C.M. Russell Museum

From our February/March 2020 issue.