In this special show at the Nevada Museum of Art, the iconic depictions of the American West by Maynard Dixon presage the advent of modernism.

Sagebrush and Solitude: Maynard Dixon in Nevada is the first comprehensive exhibition and book to document the early wanderings and extended visits of the accomplished painter Maynard Dixon to the state of Nevada, Lake Tahoe, and the Eastern Sierra. From 1901 to 1939, Dixon made several trips from his San Francisco home to paint and sketch the striking landscapes of the Great Basin and Sierra Nevada. He also wrote numerous poems during his time in the American West.

From Dixon’s first Nevada sketching trip on horseback with fellow artist Edward Borein in 1901 to his monthlong commission documenting the construction of the Boulder Dam (now known as the Hoover Dam) in Las Vegas in 1934, Dixon captured the beauty of Nevada’s open spaces as well as its developing landscape.

Among Dixon’s favorite painting subjects were old homesteads, wild horses, and stands of cottonwood trees, all of which figure prominently into over 100 paintings included in this historic exhibition. On view through July 28, 2024 at the Nevada Museum of Art, the show is accompanied by a 288-page book, published by Rizzoli Electa and designed by award-winning creative director Brad Bartlett.

We talked with Ann M. Wolfe, chief curator and associate director at Nevada Museum of Art, about Dixon’s longtime love of Nevada and the Great Basin, his creative outpourings in paint and poetry from his time there, and the advent of Western modernism evident in Sagebrush and Solitude.

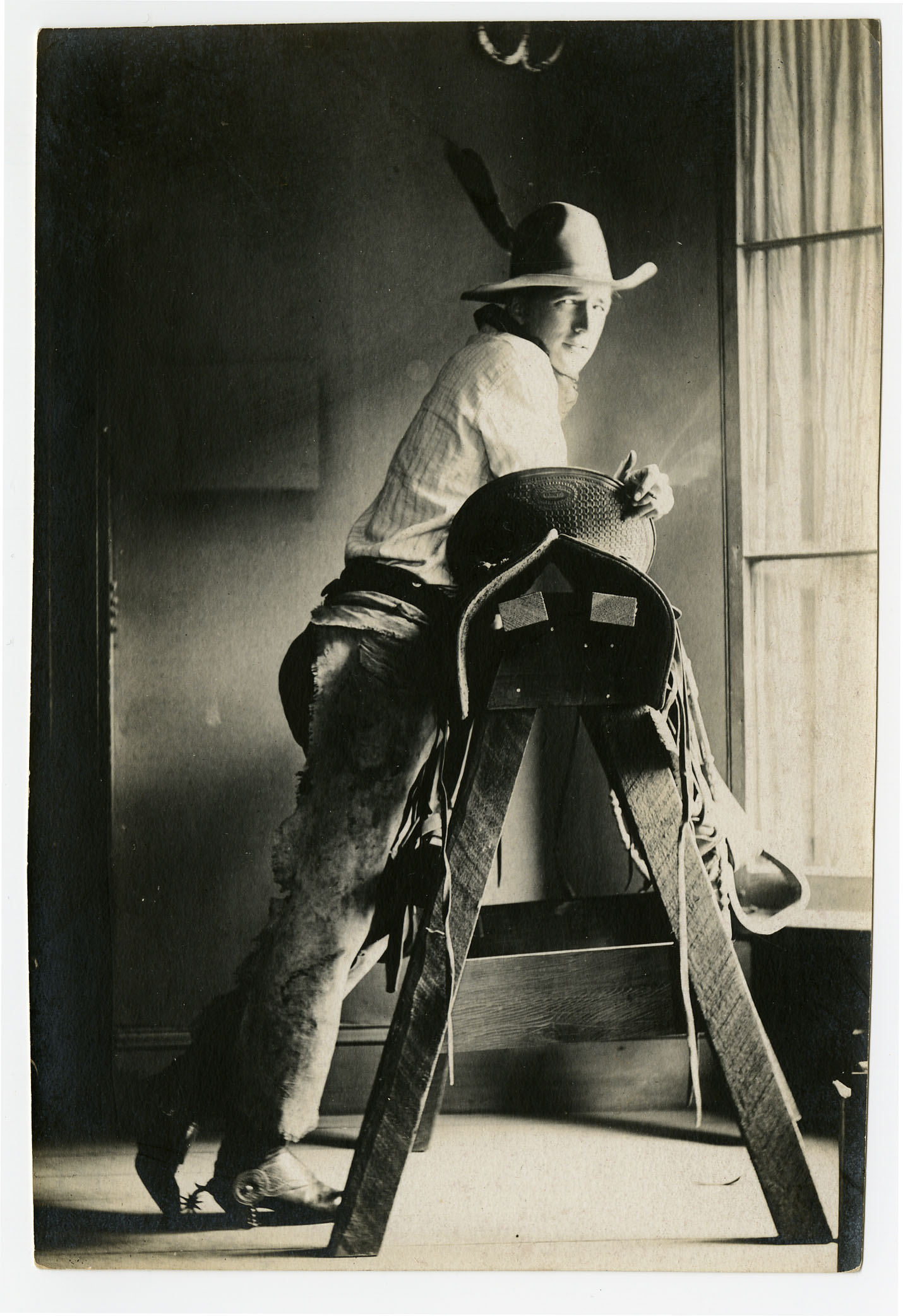

Isabel Porter Collins, Portrait of Maynard Dixon, circa 1895. California Historical Society Photographs from the Isabel Porter Collins Collection, MSP 422.

Isabel Porter Collins, Portrait of Maynard Dixon, circa 1895. California Historical Society Photographs from the Isabel Porter Collins Collection, MSP 422.

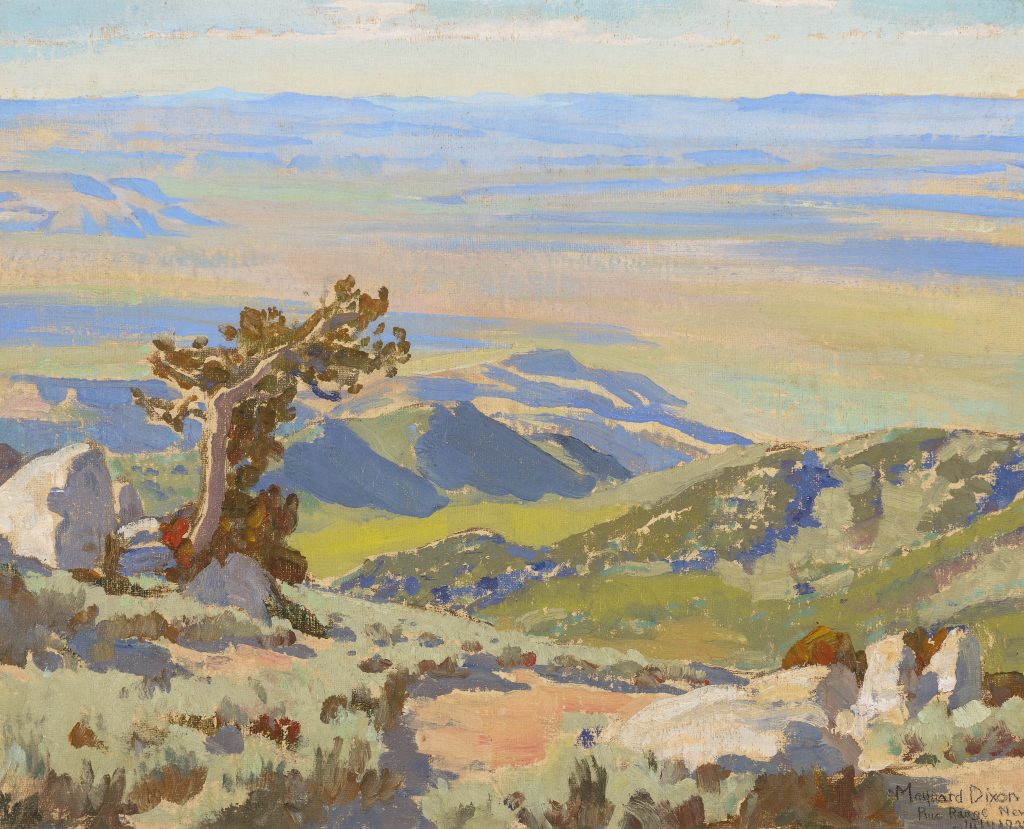

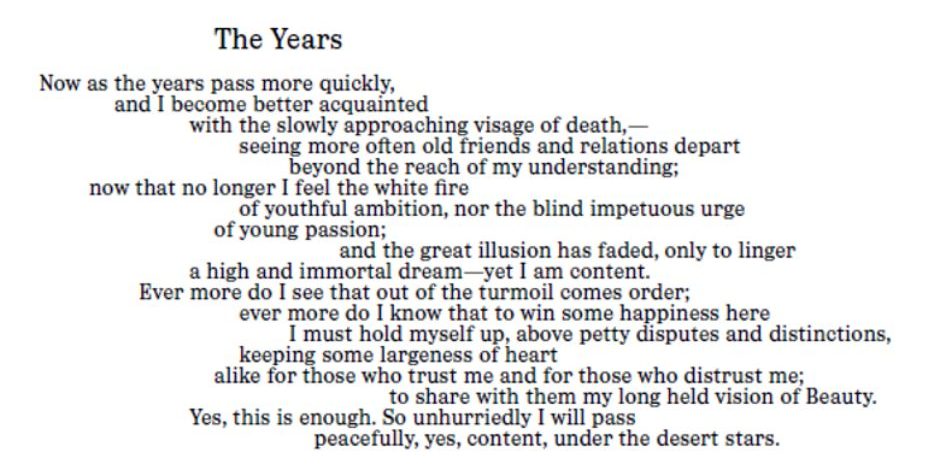

Top of the Ridge, 1933, Oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches, Framed: 45 x 57¼ in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of C.R. Smith, 1976.

Top of the Ridge, 1933, Oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches, Framed: 45 x 57¼ in., Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of C.R. Smith, 1976.

In the 1930s, ranchers regularly grazed cattle in the Sierra during the summer months. Maynard Dixon painted Top of the Ridge in his San Francsico studio following his stay at Fallen Leaf Lake the previous year. In this composition, Dixon emphasizes the arc of the horizon (rather than a traditional linear horizon line). The tree’s canopy mimics the horizon’s arc, suggesting Dixon’s growing affinity for modernism.

C&I: What gave you the idea for this exhibition, and how long did it take from conception to opening?

Ann M. Wolfe: The exhibition came together as a result of conversations a couple of years ago with renowned Dixon author and biographer Donald Hagerty. Dixon’s work in the American Southwest is well-documented, but no one had ever brought together Dixon’s work from the Great Basin — in particular, Nevada. Hagerty served as the lead scholar on this project helping to make connections to lenders and collectors. It was incredibly special to have worked so closely with Don, who has dedicated so much of his life to the research and study of Dixon’s life and art.

C&I: What was the biggest coup in putting together this historic show? Biggest challenge?

Wolfe: The exhibition, overall, is the largest show in many years to bring together so many Dixon paintings in one place from private collectors and museums. Three major paintings in the exhibition, the mural studies for the S.S. Silver State, had been dispersed many years ago and sold to different collectors. It was quite a detective project to track them down so that they could be reunited in the exhibition. There are also many original photographs, handwritten poems, publications (with Dixon illustrations), and Dixon’s sword-cane that offer unique insight into Dixon as a person.

C&I: Where does the title of the exhibition, Sagebrush and Solitude, come from?

Wolfe: In the Great Basin, sagebrush is ubiquitous. Its silver-green foliage spans the valleys and mountains of Nevada’s basin-and-range topography. It is an iconic symbol of the region and it also recalls the sense of solitude many people experience in the Great Basin — a solitude Dixon sought as well.

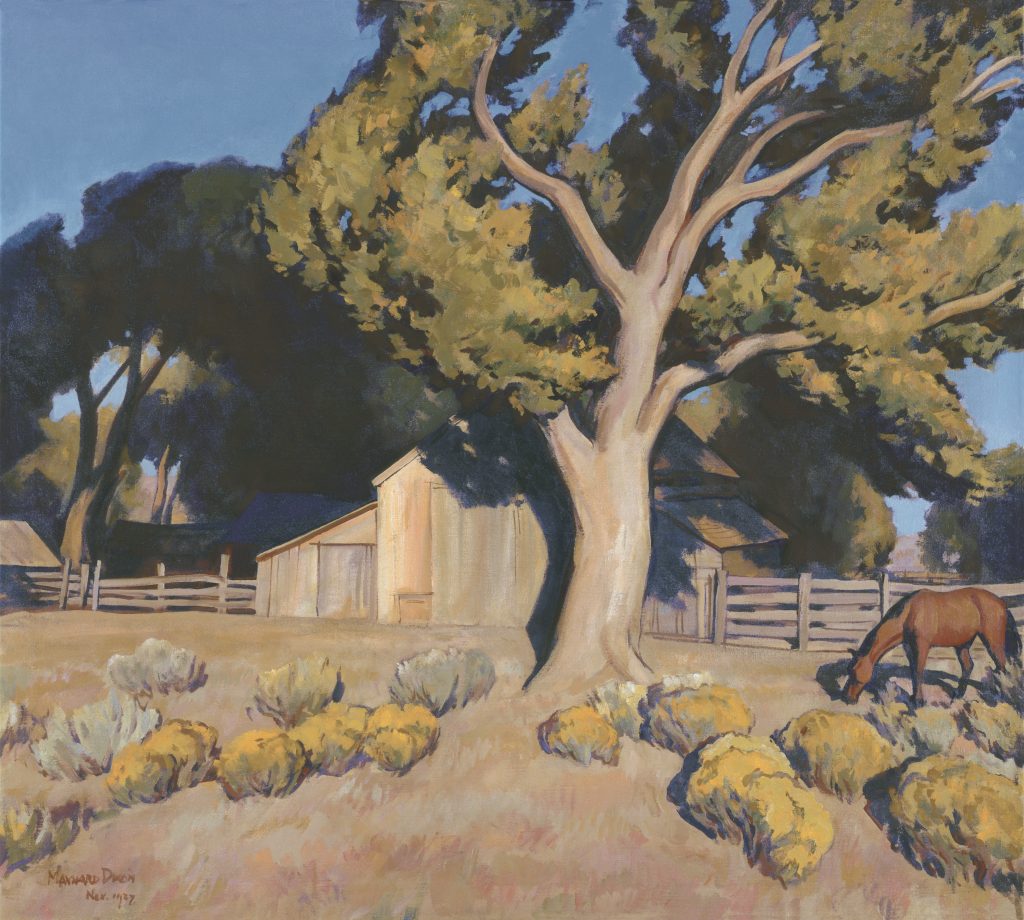

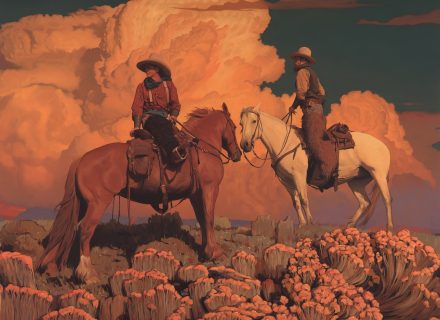

Bien Venido y Adios, 1927, Oil on canvas, 44½ x 68¾ in., Framed: 54 x 78 in., Private Collection.

Bien Venido y Adios, 1927, Oil on canvas, 44½ x 68¾ in., Framed: 54 x 78 in., Private Collection.

While staying in the bunkhouse on the Alder Creek Ranch, Maynard Dixon was intrigued by a large interior blank wall. He tacked up a piece of tent canvas and painted himself as a buckaroo astride a rearing horse. In the upper left corner of the mural, Dixon inscribed the (misspelled) Spanish words Bien Venido y Adios, which translate to “Welcome and Goodbye.”

C&I: Dixon’s connection to California and Utah are well-known. Why less so with Nevada and the art produced from numerous trips there?

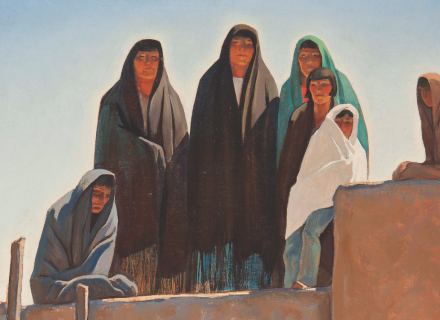

Wolfe: Although Dixon’s individual paintings from the Great Basin and Nevada are known, this is the first time they have been grouped together to reveal the quiet and introspective side of his creative endeavors. Of note is the fact that Dixon rarely, if ever, depicted the Native American people of the Great Basin. Only one quiet painting — of a group of Washoe women — is known. This contrasts with the more melodramatic and stylized depictions of Native people and Native communities he made during his visits to the Southwest.

C&I: What were the circumstances that led to Dixon’s first Nevada sketching trip on horseback with fellow Californian and Western artist Edward Borein?

Wolfe: On May 17, 1901, Maynard Dixon and his artist-friend Edward Borein (1872 – 1945) rode horseback from Oakland, California, into Carson City, Nevada, on the first leg of an epic thousand-mile ride through the northern Great Basin. With no specific destination in mind, the two artists headed in the direction of Montana. Dixon was an experienced horseman who first learned to ride while growing up in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

The notion of embarking on a solo trip — or, in this case, with fellow artist Borein — was likely inspired by Dixon’s mentor, Charles Fletcher Lummis. In 1884, Lummis had walked from Ohio to Los Angeles and then published his experience in a book called Tramp Across the Continent. Borein had traveled solo on horseback from Oakland to Mexico, where he worked on ranches as a vaquero. These ventures were likely inspired by the notion that one could truly only know and understand a place and its people through direct experience.

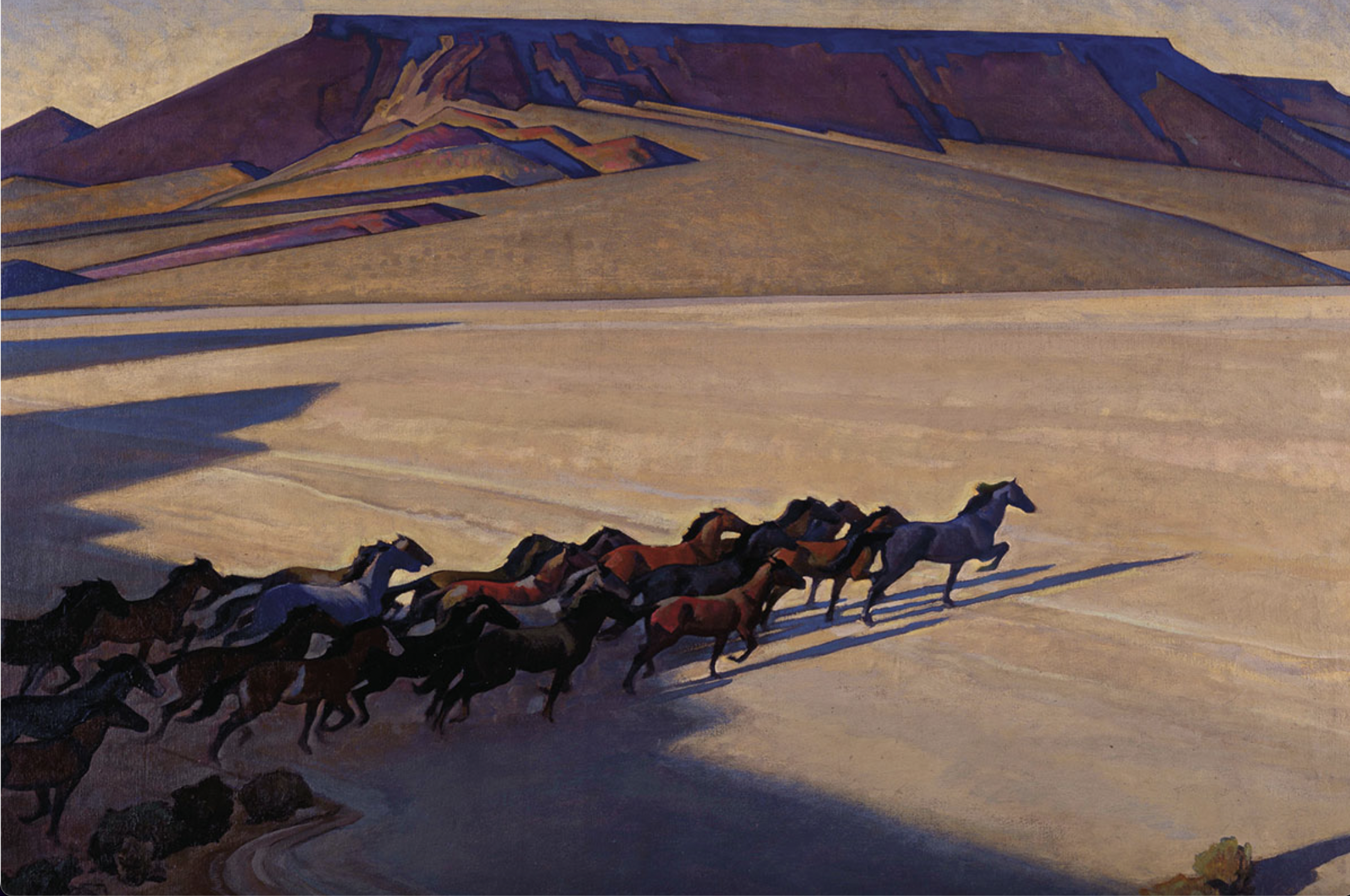

Wild Horses of Nevada, 1927, Oil on canvas, 44 x 50 in., Framed: 46 x 52 in., Collection of the William A. Karges Family Trust.

Wild Horses of Nevada, 1927, Oil on canvas, 44 x 50 in., Framed: 46 x 52 in., Collection of the William A. Karges Family Trust.

Maynard Dixon painted Wild Horses of Nevada in his San Francisco studio following a four-month visit to northwestern Nevada in 1927. The bird’s-eye view shows a band of wild horses galloping across a stark, desert alkali flat. Dixon’s choice to emphasize the geometry of the distant mountains, incorporate dramatic shadows, and to eliminate all unnecessary details are evidence of his increasing embrace of modernism.

C&I: Dixon had a month-long commission to illustrate/document the construction of the Boulder (now Hoover) Dam. What characterizes the art that came out of that?

Wolfe: In April 1934, Dixon was commissioned by the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), a New Deal work-relief program for artists, to document construction activities at the Boulder Dam. During his stay, he lived at a worker’s home in Boulder City, a community established to provide living quarters near the construction. He witnessed the difficult working conditions, and what he experienced distressed him. Other artists and photographers working alongside Dixon at the Boulder Dam produced paintings and photographs that celebrated the achievements of the project and glorified the bravery of the workers. Dixon’s paintings, on the other hand, offer an unromantic and antiheroic view of the endeavor, portraying laborers as minuscule figures set against imposing walls of rock in an inhospitable desert environment. The exhibition includes many paintings from his time in Boulder City during the construction of the dam.

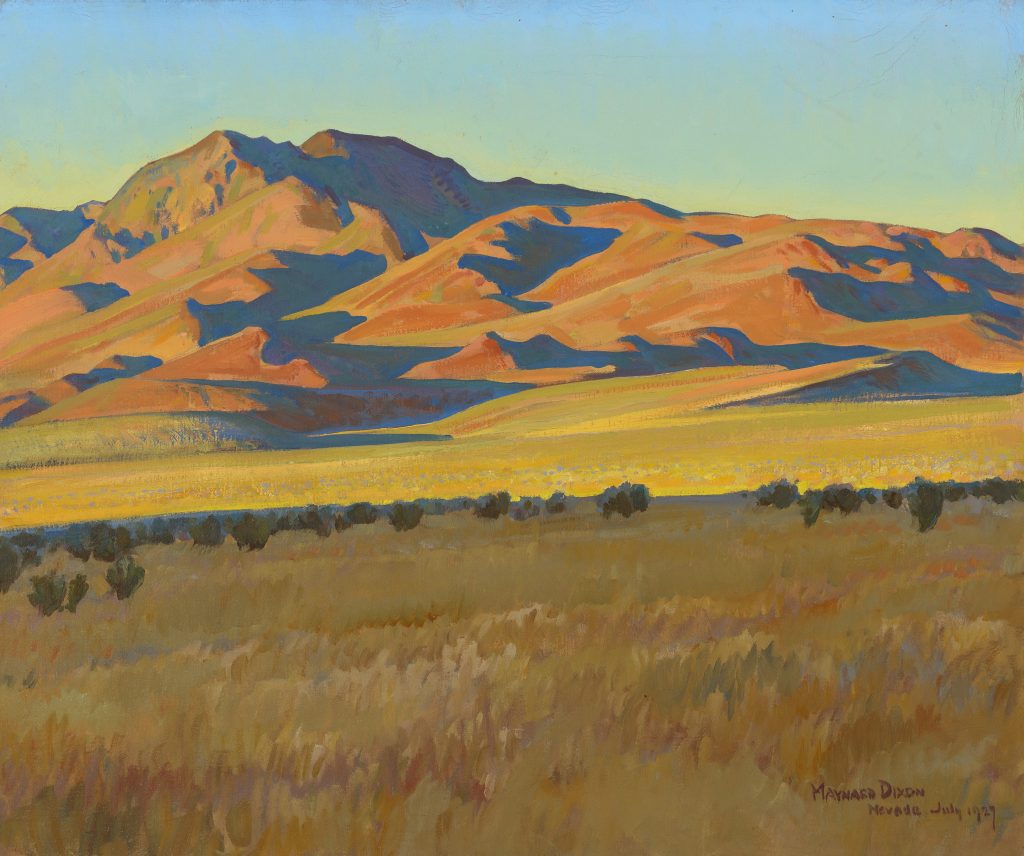

Wild Horse Country [Humboldt County, NV], 1927, Oil on canvas, 26 x 30 in., Framed: 31 x 35 in., Collection of the Society of California Pioneers.

Wild Horse Country [Humboldt County, NV], 1927, Oil on canvas, 26 x 30 in., Framed: 31 x 35 in., Collection of the Society of California Pioneers.

Set beneath a dramatic cloudy sky, Maynard Dixon painted a band of wild horses galloping across a sagebrush-studded valley in northeastern Nevada. In this modern composition, he also reduced the distant mountain ranges into simple geometric forms with little realistic detail.

C&I: How were his trips to Nevada, Lake Tahoe, and the Eastern Sierra documented? Paintings, sketches? Any journals? If he documented his trips in a journal, what are some passages that really strike you?

Wolfe: Most of Dixon’s travels to the region are documented paintings, letters, and a few photographs. I’ll focus here specifically on his time at Fallen Leaf Lake near Lake Tahoe. Dixon visited Fallen Leaf Lake and Lake Tahoe in the early 1920s and ’30s as a guest of his major patron, Anita Baldwin (1876 – 1939). He first met Baldwin, the daughter of Comstock pioneer E.J. “Lucky” Baldwin (1828 – 1909), when she visited him in San Francisco in 1913 to purchase several of his paintings.

In 1932, Dixon took his wife, photographer Dorothea Lange, and their two boys, along with the twin sons of their artist-friends Roi Partridge (1888 – 1984) and Imogen Cunningham (1883 – 1976) to Baldwin’s 2,000-acre estate at Fallen Leaf Lake near South Lake Tahoe. They spent the summer in one of the Baldwin estate’s private cottages, isolated from the ravages of the Great Depression. There was an English butler at the main house, and Baldwin’s personal bodyguard (armed with a Colt .45 pistol) rode horseback around the property’s perimeter to discourage trespassers. Lange documented the family’s visit in photo scrapbooks showing Dixon and the children enjoying a range of outdoor activities. (This is included in the exhibition).

Dixon managed to complete some paintings during his stay at Fallen Leaf Lake; even so, he described the mountain landscape in a letter as having “too many trees.” Above the tree line, Dixon could hike to where the landscape “opened up,” and he would focus in on a single tree or a small grouping of trees set against an empty sky. This approach could be considered modern compared to that of his predecessors, who aimed to depict the landscape with more topographic accuracy and precise detail. Whenever possible, Dixon descended from the mountains to explore Nevada, especially the hills around Virginia City and the Carson Valley.

Volcanic Walls, 1924, Oil on canvas, 20 x 30 in., Collection of Mary Ingebrand-Pohlad.

Volcanic Walls, 1924, Oil on canvas, 20 x 30 in., Collection of Mary Ingebrand-Pohlad.

Volcanic Walls depicts a section of the Coso Range illuminated by the late afternoon sun. The rich coloring endows the canvas with a deep glow that is reminiscent of rich, red volcanic lava.

C&I: What attracted Dixon to the region to the point that he would return to it many times and create so much art?

Wolfe: Located within relatively close proximity to his home and studio in San Francisco, Nevada’s alkali flats and sagebrush-studded rangelands offered an easy-to-reach respite from the bustling city. His frequent return to the Great Basin is a testament to his relentless search for solitude, spiritual understanding, and personal healing in the high desert.

C&I: What are some of the memorable experiences he had in the state?

Wolfe: During the late summer of 1927, Dixon headed for Nevada’s northwest corner, initially planning only a two-week excursion. The trip turned into four extremely productive months. Traveling from San Francisco to Winnemucca, Dixon met up with Frank Tobin, the son of stockman Clement Tobin. Mostly on horseback, they headed north in Nevada’s Humboldt County, where they pitched their tents in aspen groves and on remote cattle ranches. Along the way, Dixon wrote letters and composed poetry by the light of a kerosene lantern or flickering campfire.

When Dixon and Tobin reached Denio, near the Oregon border, they explored the opal mining operations near Thousand Creek Valley and visited the remote areas of Virgin Valley, Rainbow Ridge, and the Pueblo Mountains before heading south along the western edge of the Pine Forest Range. They stayed for several weeks at the Alder Creek Ranch, 40 miles north of the Black Rock Desert. Dixon produced 56 oil paintings and numerous drawings during his four-month stay in Nevada.

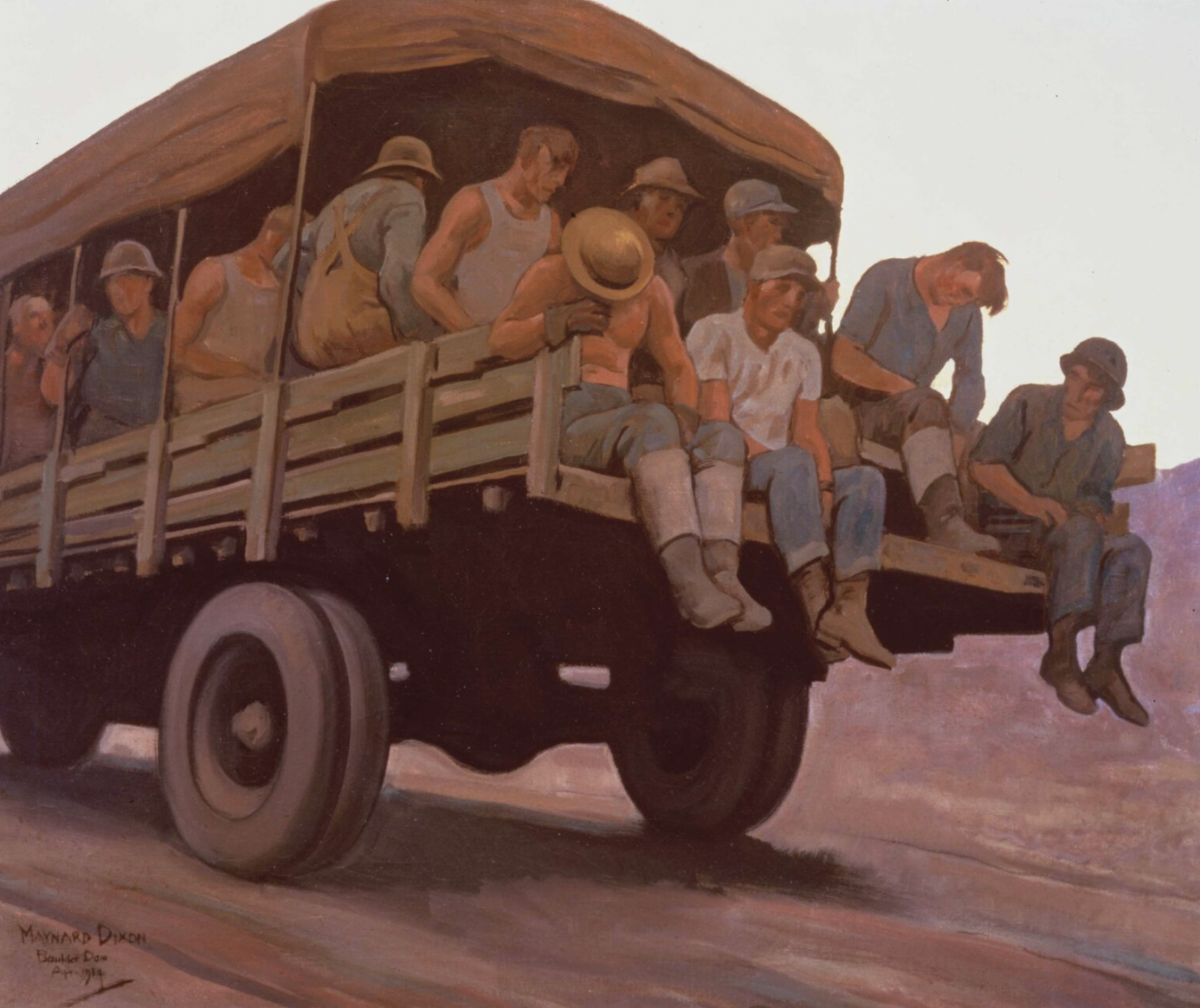

Tired Men, 1934, Oil on canvas, 25 x 30 in., Private Collection.

Tired Men, 1934, Oil on canvas, 25 x 30 in., Private Collection.

Tired Men, painted in flat light with a monochromatic palette, portrays a truckload of exhausted workers. None of the men appear to touch or make eye contact. Their slack faces, sunken eyes, and crumpled forms suggest the physically punishing and psychologically alienating nature of industrial labor. “The men seemed like robots to me,” Maynard Dixon reported to one newspaper. “I didn’t have enough time to get near enough to them to know them. But there they worked in the blazing sun at 140 degrees.” “‘It’s like war,” Dixon said of the workers. “They are fighting a great fight with bravery.”

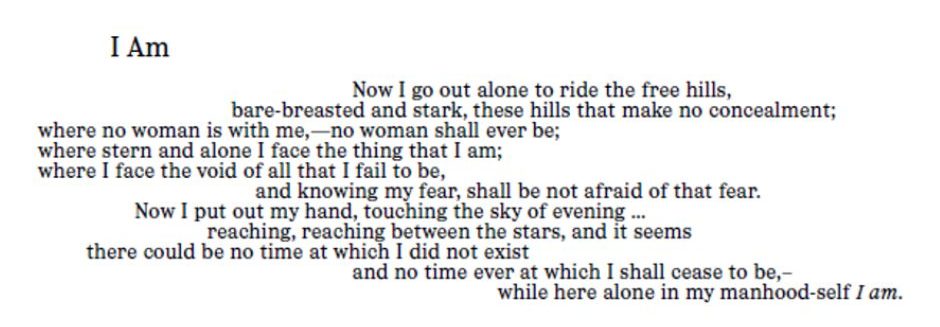

C&I: In addition to being a masterful and influential painter, Dixon was also a noted poet. How, if at all, are the poems he wrote during his time in the region used in the exhibition?

Wolfe: Dixon’s poems are interspersed among paintings on the walls of the gallery. There are also many original handwritten poems included in the exhibition. When the paint would not say what Dixon wanted, or when he was distressed by personal challenges, he frequently used poetry to express his deeply held feelings and beliefs. Dixon’s fondness for the ballad form of cowboy poetry is evident in much of his writing. However, unlike many cowboy poems or ballads, his writing isn’t particularly narrative, even though it does emphasize the “vanishing West.”

C&I: What are your favorites among the poems he wrote about the American West?

Wolfe: I particularly like “I Am” and “The Years.”

C&I: What is the place of the Sagebrush and Solitude paintings in the Dixon canon? In the canon of “Western” art? In the canon of modernist art?

Wolfe: Viewers can follow Dixon’s turn toward modernism in the transition from his pre-1920 landscape paintings to those made in the late 1920s. In paintings he made in the field during his trip to northern Nevada in 1927, Dixon begins to distill the landscape down to its underlying geometric structure by eliminating unnecessary details and employing a limited color palette. Upon Dixon’s return to his San Francisco studio, Dixon painted many canvases inspired by the Nevada landscape that were increasingly influenced by the formal principles of modernism. In doing so, he produced some of the earliest modern Nevada landscape paintings of the 20th century.

C&I: What do you hope people will experience and take away from this exhibition?

Wolfe: The work of art historians is never finished. Although Maynard Dixon is an extremely well-known and well-studied artist, this exhibition and book shed light on an entire body of work that has never been seen before together and provides new context for Dixon’s longtime love of Nevada and the Great Basin.

November in Nevada, 1935, Oil on canvas mounted on hardboard, 30 x 40 in., Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Bequest of E. Dixon Heise, 2006.33.

During Maynard Dixon’s Nevada travels, a special tree caught his attention and became a fixture in many of his paintings—the Fremont cottonwood named for the pioneering explorer of the American West John C. Frémont (1813–1890). The recognizable trees typically grow along springs and waterways in the arid high desert. As a seasoned explorer of the Great Basin, Dixon knew the tree’s promises: Its rattling and shimmering leaves often foreshadow rain, and its leafy forms on the horizon promise water, firewood, shade, and shelter to desert travelers. Many of Dixon’s cottonwood paintings were made in the Carson Valley, where the Carson River meanders through grassy meadows and pastures.

Sagebrush and Solitude: Maynard Dixon in Nevada is on view through July 28, 2024 at the Nevada Museum of Art.

HEADER IMAGE: Steers to Market, 1936, Oil on canvas, 30 x 36 inches. Private Collection.

All images courtesy of Nevada Museum of Art.