A major exhibition explores the renowned artist’s powerful paintings of the land and its inhabitants.

Editor’s Note: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West is currently closed through May 18, 2020. Please check their website for updates on when it will open again to the public for exhibitions and other programming.

Maynard Dixon was born in 1875 in Fresno, California, 10 years before the San Joaquin Valley frontier railroad town was incorporated. The son of well-to-do Confederates who left Mississippi after the Civil War and made a home out West, he exhibited an artistic bent from a young age. By 1892, before he was 20, Dixon had made his way to San Francisco to study art, traveling thereafter to Monterey and Carmel with tonalist painter Xavier Martínez, visiting Arizona and Mexico, and journeying by horseback around the West with fellow California painter Edward Borein.

A striking interpreter of the American landscape and the country’s diverse cultures, Dixon would go on to do everything from illustrate Clarence E. Mulford’s Hopalong Cassidy to advocate for the red of the Golden Gate Bridge. But it was his painting that would make him one of the most important figures in American art.

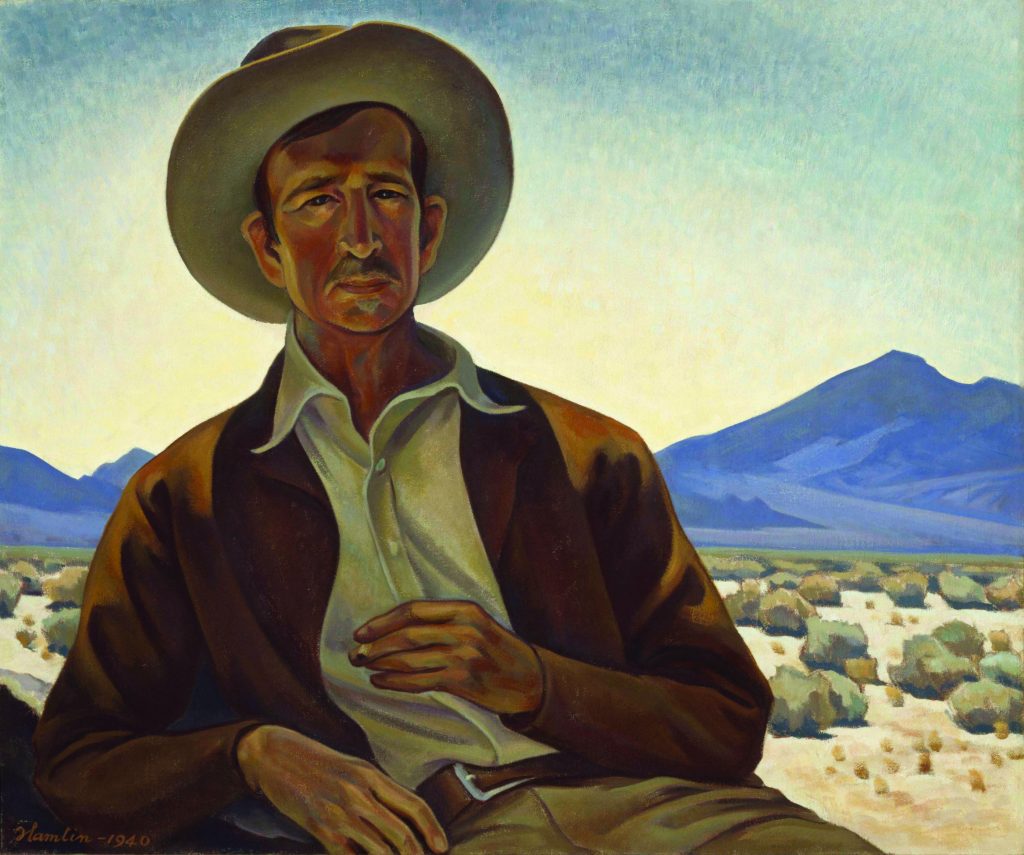

Dixon’s iconic paintings of the land and the times form the backbone of the major exhibition Maynard Dixon’s American West at the Scottsdale Museum of the West in Arizona. One of the most comprehensive exhibitions ever mounted on Dixon — including more than 200 works and the easel he painted them on — the wide-ranging show illustrates the artist’s deep sense of place in the West. Also featured is important artwork by well-known artists Dorothea Lange and Edith Hamlin, who were both Dixon’s wives and companions.

“There’s a modern sensibility to Dixon’s style that resonates greatly with artists today — it sets him apart,” says Mark Sublette, exhibition curator and author of Maynard Dixon’s American West: Along the Distant Mesa. “He thought you should focus your energy on trying to be an original voice of American subject matter, and there are artists following in his bootsteps, so to speak. Many artists working today recognize him as the grandfather of everyone.”

We talked to Sublette about Maynard Dixon’s art and legacy and the exhibition and book that capture them.

Cowboys & Indians: Congratulations on the new book and the exhibition. What inspired you to do both now?

Mark Sublette: I’ve had a Maynard Dixon museum in Tucson [Arizona] for more than 20 years. I’d always felt if I finally had enough new information to add to the body of work, I would write a Dixon book. There was enough knowledge and new things that it was worth the endeavor. The Scottsdale Museum of the West approached me about doing a show, so that was the perfect impetus.

C&I: What makes Maynard Dixon such a towering figure?

Sublette: There were multiple facets to the man that qualify him as one of the most important American painters who happens to be from — born in — the West. Most Western painters weren’t born in the West: the Taos Founders, Remington, Russell. The only other one besides Dixon was Edward Borein. Dixon and Borein actually painted together. In 1901, they took 10 horses out of Oakland, California, on a 1,000-mile horseback ride to capture cowboys in action. They were hoping to make it to Wyoming and Montana, but the horses broke down and they had to take the train back to San Francisco. They did all these wonderful drawings of cowboys at work and ranches in Northern California and Oregon; there are examples of these very rare pieces in the show.

C&I: What’s the first time you remember being awed by a Maynard Dixon painting?

Sublette: I’d been interested in his work and I’d seen it before I decided to do a show of his art in 1996. One of the first pieces was Late Light on the Catalinas (1943). It was brought in by a dealer who wanted it in the show or to sell it. I ended up falling in love with the painting. I thought, Wow, this guy is an amazing individual. I sold the painting in the 1996 retrospective, then bought it back later from the person I sold it to. I still have that painting. It’s not in the show, but it is in the book.

C&I: It’s so interesting that he was married to Dorothea Lange and Edith Hamlin, both important artists in their own right. What else might people be surprised to learn about his background?

Sublette: One of the things that set him apart is that he was intimately involved in the building of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco. From helping hire architectural engineer Irving Morrow, to doing the drawings for what it would look like and the drawings and paintings that graced the cover of the bond issue that ran in the newspapers that helped to pass the $35 million bond, to the fact that it was Dixon who wrote Morrow and told him, “If you want it to be the wonder of the world, keep it the under color of red — not black or a dark color.” He was also involved with the Boulder Dam as part of a PWAP [Public Works of Art Project] to go and document the building of the dam. For 35 days in April 1934, he captures the essence of what’s going on with man against mountain. ... During that time, four men died and the hospitals were full [of injured dam workers]. So he has an intimate look at what’s going on in America in some of the largest architectural undertakings of the 20th century. He also does a two-panel mural [for the Bureau of Indian Affairs] in the main Interior building; the 25-by-34 oils that were the studies for those murals are in the show.

C&I: He also wrote poetry.

Sublette: Dixon says, “All my poet friends say I’m a good painter and my painter friends say I’m a good poet.” He was an excellent writer and poet and in 1923 had a book of his poems published. He starts writing poetry in 1896. His poems are deep examinations of his life, emotions, and feelings he’s experiencing in different periods associated with paintings or what our country is like and his own world as it spirals out of control during the Depression, World War I, and divorces from two wives. The poems are snapshots — always emotionally charged and beautifully written in script. There are numerous examples of poetry in his hand throughout the exhibit.

C&I: Dixon’s art is pioneering, unique, recognizable. Would you call his work iconic?

Sublette: Yes, his work actually is iconic. Iconic to me means you associate something, whether verbal or visual, with something else. There’s a bond, a connection that you experience with Cloud World (1925) or Earth Knower (1931, 1932, 1935), a painting of a Native American juxtaposed against huge rocks. You know you’re speaking of the West. You have no doubt that this couldn’t be anywhere but the West. He is able to evoke an emotion of whatever it is that he’s trying to portray. In Earth Knower, the individual is one with the land. Cloud World portrays small riders against a huge landscape — man is insignificant and just passing through. A lot of his paintings evoke these emotions. Clyfford Still’s biographer says Earth Knower was an important painting even to an abstract expressionist; he found it to be iconic.

C&I: What’s another piece you’d single out?

Sublette: Dixon himself considered his greatest work Shapes of Fear. That pivotal and important painting is in the show, along with two studies. He starts Shapes of Fear in 1930, in the throes of the Depression. It portrays robed figures that are very ominous — Dixon uses that word. He feels like there’s a vise around his neck when he’s painting it, so severe is his concern for what is going on in his world. In 1931, he enters the painting in the San Francisco Art Association’s annual exhibition and wins the most popular painting award, the Harold L. Mack, beating out Edward Hopper, Diego Rivera, William Glackens. It clearly struck a chord. In 1932, he enters it in the National Academy of Design show in New York and wins the Henry W. Ranger award; the $1,500 prize money, he says, “saves my life.” That award is considered to be the premier painting of that year. Shapes of Fear is the great painting of 1932. The studies for it are in the Maynard Dixon Museum collection; the oil is in the Smithsonian collection — you can see all of them in the show in Scottsdale.

Maynard Dixon’s American West is on view through August 2 at Scottsdale’s Museum of the West (scottsdalemuseumwest.org). The Maynard Dixon Museum is in Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson, Arizona (medicinemangallery.com). Catch Mark Sublette’s podcast, The Art Dealer Diaries — which covers the West, writers, artists, collectors, and dealers — on YouTube.

Images: Courtesy Phoenix Art Museum, Oakland Museum of California, Adrienne Ruger Conzelman, Karges Family Trust, James Hart Photography, Smithsonian American Art Museum