More than a century after the West’s most notorious trial, people can’t stop talking about the epic life and controversial death of cowboy legend Tom Horn.

Why would you confess to a crime you didn’t commit? Particularly one as heinous as the cold-blooded murder of a 14-year-old boy? And do so in the presence of a federal lawman you knew considered you a suspect in the case?

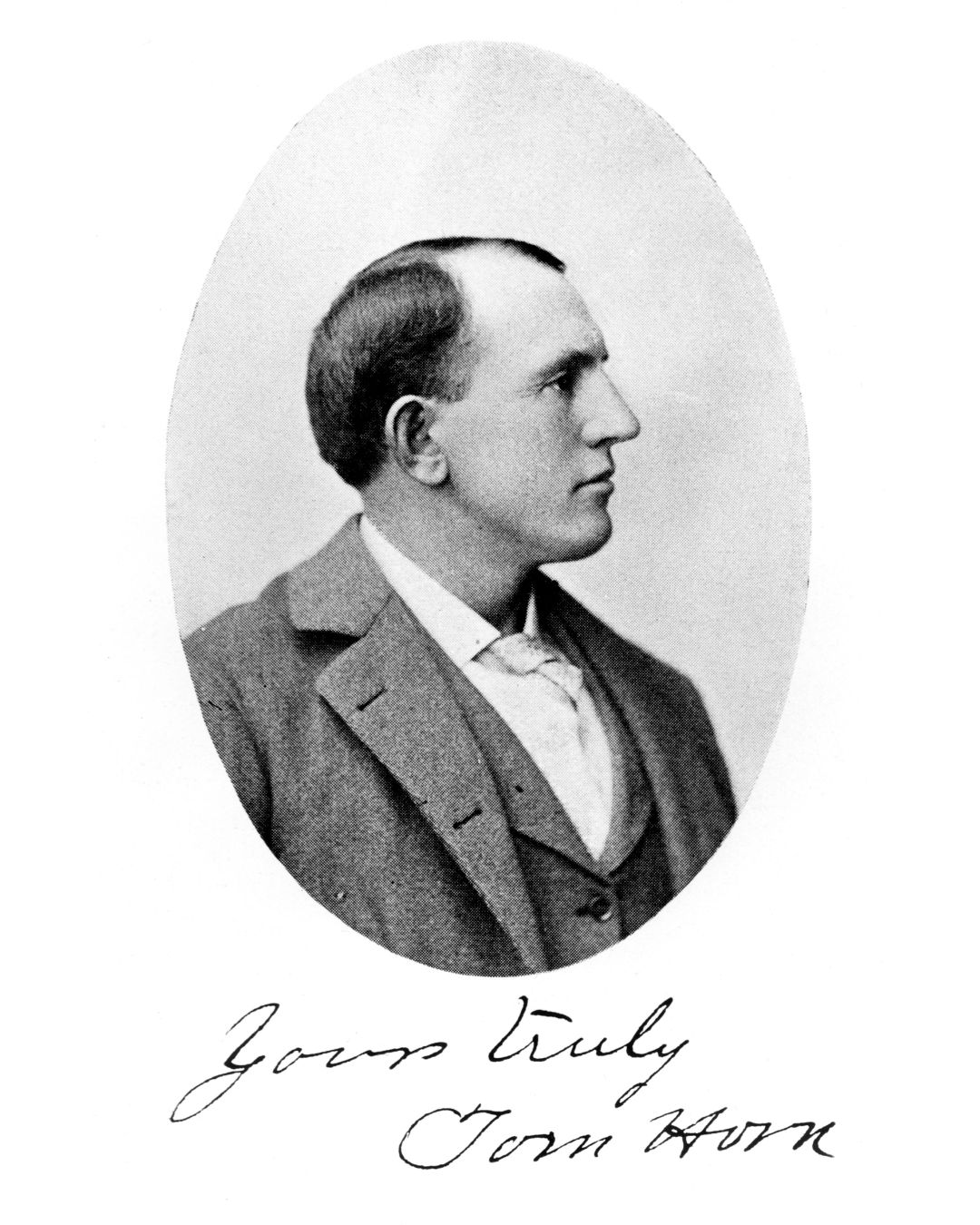

These questions have always been central to the mystery surrounding the extraordinary 1902 trial and conviction of Tom Horn—one of the most notable and capable cowboys of the frontier era—and his subsequent hanging in Cheyenne, Wyoming, on November 20, 1903.

Despite the evident confession Horn delivered to Deputy U.S. Marshal Joe LeFors in a Cheyenne law office, once in court the so-called King of the Cowboys steadfastly maintained his innocence. His trial ranks among the most sensational in American history, his legend one of the West’s most enduring and controversial.

Held each August (August 11–13, 2023) in Bosler, Wyoming, Tom Horn Days are celebrated with concerts, rodeo events, camping, Sunday morning cowboy church, and history presentations.

On October 12, the Wyoming State Archives will reaffirm our ongoing fascination with the cowboy killer when it hosts a Tom Horn Research Panel as part of its speakers series at the Laramie County Library in Cheyenne. Along with the ghosts of the principal figures involved—not least being 14-year-old Willie Nickell—hanging over the proceedings will be Horn’s strange confession, why so many people believe it, why so many don’t, and why so many still care.

“We’re expecting a large crowd,” says Robin Everett of the state archives. “That’s why we moved the event to the county library.”

“Thoroughly Western” Man

It’s easy to understand Tom Horn’s mystique. The broad strokes of his Gump-like career are literally the stuff of legend. Born in Missouri in 1860, he left home at age 14 and made his way west, early on to Arizona. After kicking around as a prospector and cowhand, he hitched on as a civilian mule packer for the U.S. Army, rising to chief of scouts during the Army’s final campaign against Geronimo in 1885–86.

Along the way he served under legendary Army scout and guide Al Sieber, lived among the Apaches, and became so fluent in their language (and Spanish) that he served as an interpreter for Geronimo. He was a member of the party that founded the camp that became Tombstone, Arizona; a ranch foreman; gifted horse breaker; champion steer roper and rodeo pioneer; operative of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency; and civilian mule packer who supported Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

Just as violence shaped the West, it shaped Horn. As the range wars of the 1890s intensified in Wyoming and Colorado, Horn rented himself out to wealthy cattle barons who needed a hard man to force out rustlers, homesteaders, sheepmen, and other rivals to their dubious claims on vast swaths of public land — by any means necessary. According to one estimate, Horn committed as many as 17 killings as a hired gunman during his lifetime.

“If I get killed now I have the satisfaction of knowing I have lived about 15 ordinary lives,” Horn said before going on trial for the murder of Nickell.

“Horn was thoroughly Western,” wrote his cattle rancher friend John Coble in 1904, shortly after Horn was put to death. “Being Western, his conversation was replete with local expressions, not always elegant, yet rarely profane and never vulgar.”

In the decades immediately following his hanging, one day shy of his 43rd birthday, most of the known details about Horn’s life came from a single source—Horn himself. While awaiting the noose in a Cheyenne jail cell, Horn wrote his autobiography. Titled Life of Tom Horn, Government Scout and Interpreter and published in 1904, it remains a classic of Western literature. Thrilling and fast-paced (Horn’s writing feels remarkably modern), it presents a vivid picture not just of the author’s endless manly feats, but of life in the wild frontier of the Southwest and Rocky Mountains. In one passage Horn recounts his life among the Apaches, where he picked up the name “Talking Boy.”

“Well, my son, you are an Apache, now,” Horn writes of a conversation with a chief named Pedro. “So, here I was, in the latter part of ’76, a full-fledged Indian, living in Pedro’s camp as a Government agent, though receiving $75.00 a month as interpreter. I got along well, considering everything; hunted to my heart’s content, and game was plentiful.”

It’s a great book. There’s just one caveat.

“It is a rousing story, it’s a fun read,” says Larry Ball, professor emeritus of history at Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, whose 2014 book Tom Horn in Life and Legend is the most complete scholarly account of the Horn’s life. “But you need to take it as almost fiction in many ways. I researched the documents—especially military records—and did find that Tom Horn was at most of the battles he claimed he was in. But it’s pretty clear that he was not doing everything that he claimed he did.”

For all his undeniable talents, Horn had an Achilles heel. A pair of them actually—alcohol and a big mouth. When the two got together, they often led Horn into trouble. He once got his jaw broken by the manager of a professional boxer after picking a fight in a Wyoming bar.

“Horn was this insecure personality that loved to brag about himself,” says retired attorney and lifelong Wyoming resident John W. Davis, whose 2016 book The Trial of Tom Horn is the gold standard examination of the celebrated court case. “He’d killed a couple of men in Colorado. In Laramie County he would go into the bars and get drunk and brag about it. If you had some jerk going around doing that in [your] small town it would cause a lot of negative feeling.”

“He was, I’m certain, drinking heavily by the time he died,” adds Ball. “There’s evidence he contracted yellow fever or malaria or something in Cuba. People who knew him remarked that when he came back from Cuba he was never quite the same.”

Ball calls out Horn’s “big ego” and penchant for making exaggerated claims about himself. All of these qualities—outsize reputation and inflated sense of self, among them—would eventually come together to doom Horn.

Dirty Tricks

On July 18, 1901, 14-year-old Willie Nickell—the son of a sheep rancher described by Davis as “a quiet, well-behaved boy”—was shot twice from long range. The bullets tore through his sternum, intestines, and aorta. He died quickly, about three-quarters of a mile from his family’s homestead in an area of southeastern Wyoming known as Iron Mountain. Wearing overalls, a vest, and light hat, Nickell had been alone, running an errand on horseback. There were no witnesses.

Although the boy’s father, Kels Nickell, had a quarrelsome reputation and was involved in a running dispute with a neighboring family named Miller, the grisly and senseless murder of the youngster shocked the entire state. Public interest in the subsequent investigation was fueled by swelling anger over the lawless behavior and perceived impunity enjoyed by the powerful cattle cartels that controlled much of the territory.

At the time a private range enforcer working for cattle ranchers in the Iron Mountain area, Tom Horn became one of several early suspects. In order to drive Kels Nickell and his sheep from the area, so went one theory, the cattlemen had hired Horn to kill his son. Or perhaps the father.

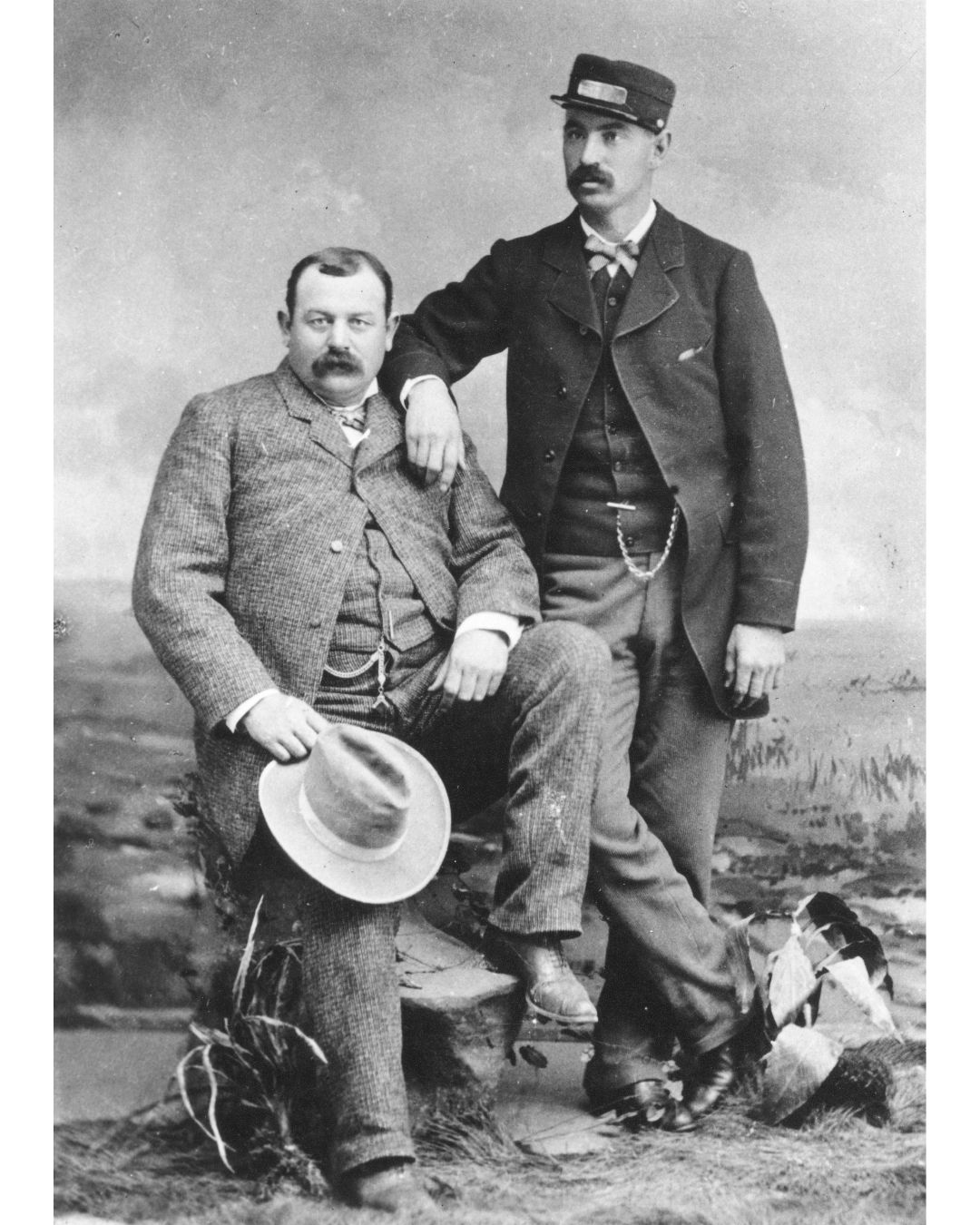

Without witnesses or hard evidence—whoever the killer was, he’d expertly covered his tracks—the case went cold even as public demands for justice grew louder. Tasked with picking up the investigation, Deputy U.S. Marshal Joe LeFors was told by his boss: “If you can bring those lawbreakers to justice, you can get any position the state has to offer.”

“At the time the feeling was running high and the demand was for justice,” LeFors would recount in his autobiography. “I knew those Cheyenne politicians were for politics first and justice next.”

LeFors suspected Horn was the murderer and devised a scheme to trap him. Luring the cowboy into his Cheyenne office with the promise of a (phony) job offer from cattlemen in Montana looking for some illicit muscle, LeFors manipulated Horn into a booze-fueled conversation about his very particular set of skills. What Horn didn’t know was that in an adjacent room, LeFors had stationed a credible witness and a court stenographer to transcribe the conversation. According to some accounts, to aid their vision and hearing, LeFors had an inch planed off the bottom of the connecting door and peepholes bored in the wall between the rooms. (The scene is portrayed in the 1980 film Tom Horn, with Steve McQueen playing the title character and a crackling screenplay by legendary Western writers Thomas McGuane and Bud Shrake.)

As LeFors suspected, Horn warmed to the chance to embroider his tough-as-gristle reputation.

“Killing men is my specialty,” Horn boasted to LeFors, who was five years his junior.

“How far was Willie Nickell killed?” LeFors asked.

“About 300 yards,” answered Horn. “It was the best shot that I ever made and the dirtiest trick I ever done.”

“[Horn] spilled his guts on everything,” Davis says. “LeFors was very skillful in pulling this stuff out. He assessed very clearly that Horn was this insecure personality that loved to brag about himself.”

Hard Case

Armed with such a stark confession, the prosecution came into the Nickell case with what appeared to be an insurmountable advantage. Once formally charged, however, Horn retracted his confession with what for any other man would have been a laughably flimsy defense. Horn insisted he was just kidding when he told LeFors he’d killed Nickell. Joshing is the word that came up again and again in newspaper coverage of the trial. Horn may have been leaning on his reputation as a known bullshitter, but, even so, it’s hard to conceive of a less-convincing defense.

“Horn’s ‘just joshing’ defense is lame, but it’s what he came up with and stuck to,” says Davis. “In general, Horn did not have good judgment.”

Horn’s legal team wasn’t completely forsaken. Soon after the trial got underway, they began shooting holes through the state’s case. For starters there was the dubious manner in which Horn’s confession had been obtained via LeFors’ setup. One witness placed Horn far from the scene at the time of the murder. The presentation of a blood-soaked sweater supposedly worn by Horn at the time of the killing belied the methods of an expert killer so careful he’d walked barefoot over rough ground to hide his tracks at the scene of the crime. Though inadmissible as hearsay, a local schoolteacher named Glendolene Kimmel produced an affidavit swearing that on three occasions she’d overheard members of the Miller family (with whom she boarded) claiming credit for the killing of Nickell.

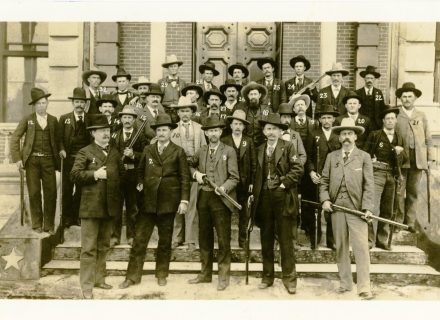

It required perhaps the state’s best attorney, Walter Stoll, to win a guilty verdict from the jury. A local newspaper described the prosecutor’s summation as a “masterpiece of forensic oratory.”

“I am not … afraid of the evidence,” Horn said during the trial, “so much as Stoll.”

“If Stoll had not been so absolutely superb, Horn would have won his case,” says Davis. “I’ve cross-examined a lot of people, and what Stoll did was absolutely genius.”

Defense attorney John Lacey pounded at flaws in the prosecution’s case. To no avail.

“The primary reason it didn’t matter is every time the defense mounted a seeming telling blow against the prosecution, Stoll would come up with some astonishing, brilliant cross-examination and just kill [Lacey]. Just kill him,” says Davis.

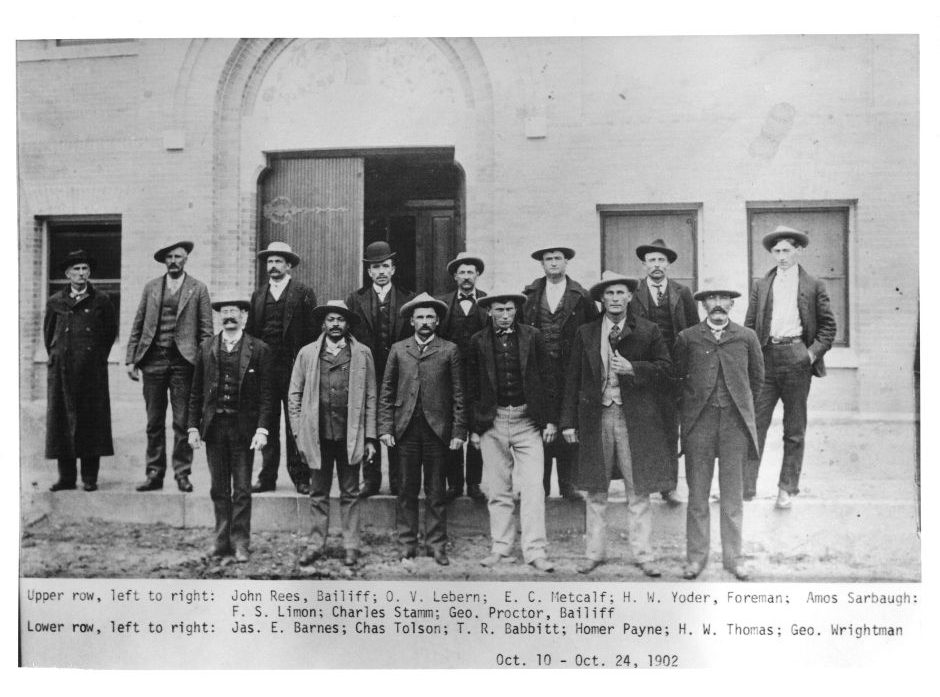

The jury deliberated for a single afternoon. Its verdict has been debated ever since. In 1993, a mock retrial, staged in part by Horn author and expert Chip Carlson, returned a “not guilty” verdict.

“In the retrial, [Horn’s defense attorney] cast considerable suspicion on Jim Miller and his son, Victor, who had feuded with the Nickells for years, leading to several fights, whippings, and stabbings,” reported the Los Angeles Times.

Carlson, who died in 2022, remains a venerated figure in the ecosystem that’s thrived around the Horn mythology for 120 years.

“Carlson believed Horn was not guilty of killing Willie Nickell but concluded that Horn was hanged for prior offenses,” says Ball. “He was a bit disappointed in me because I didn’t agree with him about Horn’s innocence. But we were good friends, and he was always gracious and courteous.”

That sense of civility and respect will no doubt prevail when the legend of Tom Horn is rehashed yet again this fall in the Laramie County Library. An ability to overlook not just personal flaws but serious sociopathic behavior in our heroes is a strange yet common contradiction of the human mind. Horn is an example, but so are Bonnie and Clyde and any number of musicians, athletes, politicians, and public figures.

“There’s always something new to learn when looking at primary resources,” says Wyoming State Archivist Sara Davis. “I think the many hats Tom Horn wore over the years is what makes him so interesting to research.”

The singular characteristic that seems to draw fans and critics together around Horn is the connection he provides to a fabled world whose legacy many of us are at times also willing to embellish. And protect.

“I have a copy of the original edition of Tom Horn’s autobiography that came out in 1904,” says Ball, who along with Davis is a scheduled panelist at the Wyoming State Archives event in October. “On the cover is a symbolic representation of Horn on horseback up on a hillside, looking for rustlers. He’s guarding the herd. That’s the image of what people still think of him. He’s out there still guarding the cattle.”

To say nothing of protecting his own legend, more than a century after his final desperate act.

The Wyoming State Archives Speakers Series: Tom Horn Research Panel takes place October 12 at 7 p.m. at the Laramie County Library in Cheyenne, Wyoming. It’s free to the public in person, or to attend online via Eventbrite. For more information, visit wyoarchives.wyo.gov.