From the anthology Texan Identities comes this fascinating chapter “Texas Rangers in Myth and Memory,” by Jody Edward Ginn.

Editor’s Note: One of the most iconic groups of Texans is the Texas Rangers. Formed during the Republic period as a volunteer mounted force to protect settlers on the frontier, they have played a key role in the development of modern Texas and especially the construction of a Texas identity. As Jody Edward Ginn shows in his insightful essay, much of early Texas Rangers historiography was the collective product of myth and memory. Their image, as projected by early historians, the mass media, and individual Rangers, was one of an invincible fighting force charged with the advance of Anglo-American democracy and Manifest Destiny. Not surprising, such early traditional accounts tended to romanticize and mythologize the Rangers’ place in Texas history.

Editor’s Note: One of the most iconic groups of Texans is the Texas Rangers. Formed during the Republic period as a volunteer mounted force to protect settlers on the frontier, they have played a key role in the development of modern Texas and especially the construction of a Texas identity. As Jody Edward Ginn shows in his insightful essay, much of early Texas Rangers historiography was the collective product of myth and memory. Their image, as projected by early historians, the mass media, and individual Rangers, was one of an invincible fighting force charged with the advance of Anglo-American democracy and Manifest Destiny. Not surprising, such early traditional accounts tended to romanticize and mythologize the Rangers’ place in Texas history.

In the early nineteenth century, as the Texas Rangers evolved from a loosely organized militia to a professional investigative force in the twentieth century, revisionist writers began to challenge earlier notions of Anglo superiority and Ranger justice. Such works were just as rife with myths and stereotypes as the traditional accounts. Some more recent Texas Rangers scholarship, however, has provided a more inclusive and balanced, less-romanticized or racially divided narrative, thereby pushing the discourse into a new era. Along with a basic understanding of the historical creation and purpose of the Texas Rangers, this essay exposes many of the myths and memories surrounding Texas Rangers history, showing how they have influenced academic historiography and public perception of their place in Texas history over time. In so doing, however, it does not seek to be comprehensive. Like the Alamo, the Rangers have a complexity in the story of Texas that precludes any single analysis from examining all of the nuances that speak to their place in myth and memory as enduring influences on identity.

—The above and following are excerpted from Texan Identities, The University of North Texas Press, 2015. Used with permission.

Texas Rangers in Myth and Memory

Other than the Alamo defenders, no group of Texans has been more eulogized and mythologized than the Texas Rangers. They have played a key role in the development of the Texas identity, and many aspects of Texas Rangers history continue to evoke very strong emotions—both positive and negative. As historian Glen Sample Ely noted, “whoever controls Texas history also influences Texas identity,” and the Texas Rangers have held a dominant place in the telling of the story of modern Texas since the days of the Republic. Their depiction, in both the Anglo-centric traditionalist academic historiography and throughout popular media—as the prototypical pioneer-patriot archetype charged with leading the advance of Anglo-American democracy in fulfillment of Manifest Destiny in Texas—has positioned them as an inextricable component of Texan identity.

While their overall significance in the creation of modern Texas is certainly substantial, this study will show that there are many perspectives on the value of and justification for the actions of the Rangers in many circumstances. It will also show that none of these perspectives are immune to mythmaking.

The key element associated with the Texas Rangers in the collective myth and memory of many Anglo Texans is the perception that the Rangers have always been invincible, incorruptible, and indefatigable defenders of justice. This image was created by early historians and embedded into the national and international collective memory of the Texas Rangers by the news and popular media, since at least the U.S–Mexican War. But the extensive mass media attention they have received throughout their history has been a double-edged sword: they have been the beneficiary of some myths and the victims of others. In some quarters, the Texas Rangers have been lionized as fearless, incorruptible demigods; in others, vilified as murderous tools of an oppressive and racially discriminatory establishment. As this study will reveal, the historical evidence evokes a far more nuanced view than either of those simplistic perceptions, and such viewpoints often depend in large part on the particular time, place, event, and specific participants involved. Myth and memory have often been intermixed with many of the available historical facts, along with both the remembering and forgetting of many aspects of Texas Rangers history.

Notwithstanding the different perspectives on aspects of their history, the Texas Rangers have long been recognized and feared around the world as a fierce and effective fighting force. As Charles H. Harris and Louis R. Sadler point out in their study, The Texas Rangers and the Mexican Revolution, “[They] are arguably the most celebrated lawmen in the world, their fame ranking with that of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Scotland Yard, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.” The comparison is all the more remarkable given that the others mentioned are national organizations with thousands of employees, while the Texas Rangers are a state-level entity with only a fraction of the personnel employed by these other organizations. The Rangers’ international prominence, despite their limited size and regional area of operations, merits an examination of how this legacy was built.

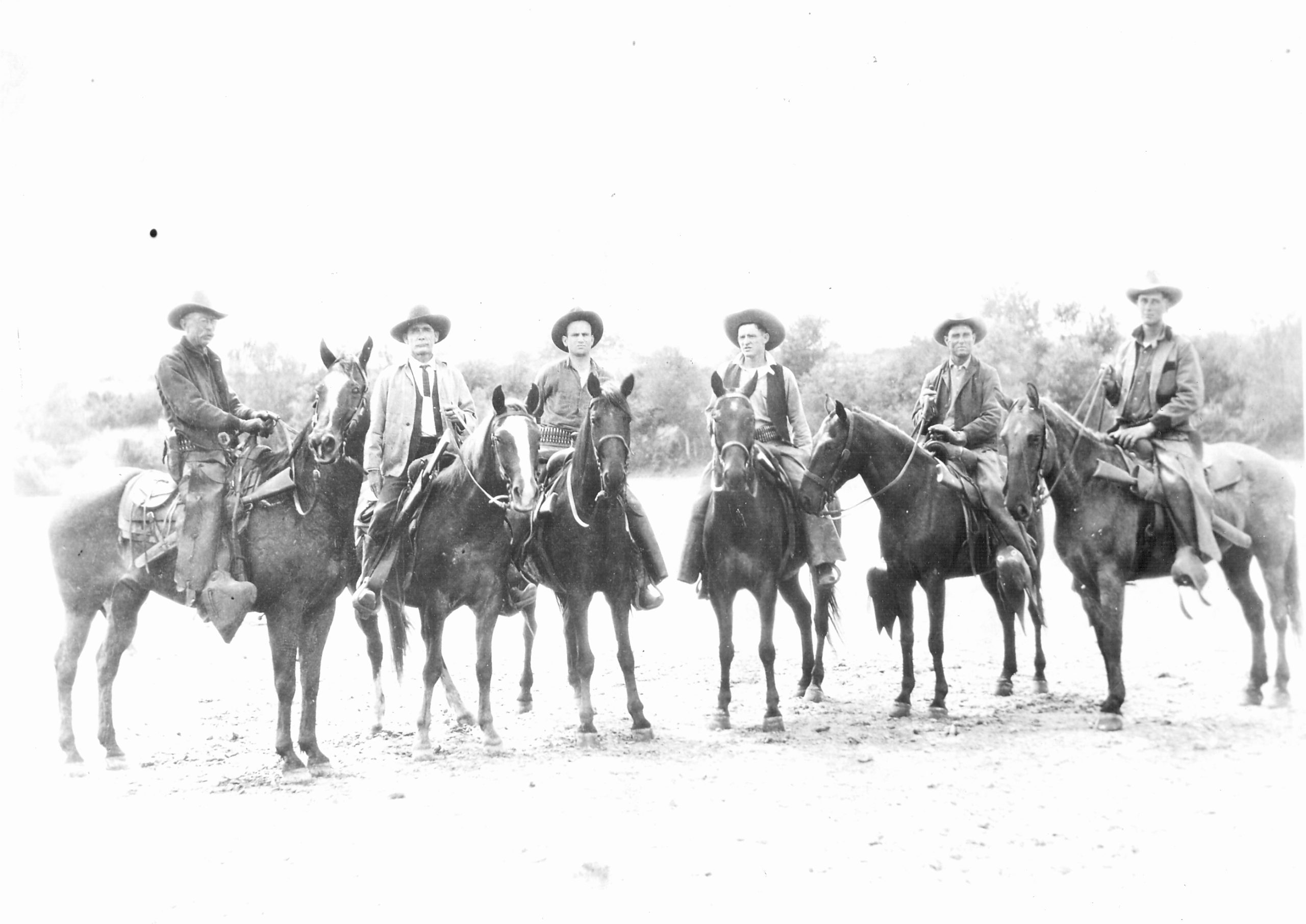

A basic understanding of the creation and purpose of the Texas Rangers is necessary in order to identify and assess the myths surrounding them. Officially founded in 1835 as a paramilitary mounted frontier force, the Texas Rangers were tasked primarily with defending settlements in the fledgling Republic of Texas against Indian raids and attacks. But Stephen F. Austin and his Anglo-American colonists did not step into a cultural, political, or military vacuum when they began settling in Mexican Texas in 1821. Since the end of the seventeenth century, units of mounted troopers known as compañías volantes (flying companies) had scoured the Indian trails and haunts across the northern frontier of New Spain, and later Mexico, in an attempt to pursue and destroy native bands that had resisted Spanish hegemony and frequently raided their frontier communities. By the time Anglo settlers began arriving in Texas, Tejanos and their forebears had been serving as specialized mounted frontier counter-insurgency troops for over one hundred and forty years. Upon their arrival, Austin’s colonists were given detailed instructions in the formation and operation of traditional Tejano flying companies for purposes of local defense, by both Mexican authorities and their Tejano neighbors. Based on their Anglo-American frame of reference for non-traditional mobile military scouting units from life in the burgeoning United States of America, Austin and his colonists informally applied the familiar terms “ranging” and “rangers” to these duties, which was eventually codified by the Consultation once independence was declared and by the Congress of the Republic of Texas after independence had been achieved.

The nomenclature “Texas Rangers” was merely an informal designation during the first 100 years of their history. Until the creation of the “Texas Rangers Division” of the Texas Department of Public Safety in 1935, the various units historically recognized as having rendered “ranging service” up until that time served under a wide variety of designations. In 1836, the new Texas Congress created the “Corps of Rangers,” through an act encompassing units that had been performing such duties for more than a year previous to its passage. The units of “citizen soldiers” who served under that and subsequent Republic and early statehood-era legislation were known as “mounted rifles,” “mounted spies,” ”mounted volunteers,” “minutemen,” and even “partisans.” However, many of those who served in such units commonly referred to themselves informally as “Texas Rangers,” as did many members of the general population.

In 1874, they gained permanent institutionalization as the administratively-designated “Frontier Battalion,” and “Frontier Force”—still a military unit intended to perform an identical role to their predecessors, only with hopes for more efficiency and effectiveness as a full-time, permanent, and mounted frontier fighting force. Shortly thereafter, the frontier came to a close and the Rangers’ slow and sometimes halting evolution into law enforcement began. This progress, however, would be impeded by events and assignments more suited to a military solution, particularly in the region of the Texas-Mexico international border. Shortly after the creation of the Frontier Battalion, the United States Army finally succeeded in relocating and subjugating even the most recalcitrant Comanches and other Plains Indians north of the Red River, leaving the Texas Rangers with little to occupy their time patrolling the frontier. As a result, the Rangers of that time slowly took up peace-keeping/law enforcement duties, which, in the beginning, primarily involved tracking and arresting fugitives from justice. The Rangers undertook such assignments often on behalf of county and city officials, who did not have the manpower or range of jurisdiction to pursue outlaws who sought refuge from justice far out on the frontier. The Frontier Battalion Rangers received neither law enforcement training nor official authority in the beginning, but they were expected to adapt and serve as needed on the “violent, crime-ridden” frontier.

Their role as lawmen was so nebulous at the time that legal issues finally arose over their involvement in such duties, leading to lawsuits and eventually to legislative action. This prompted an additional step forward in their evolution from paramilitary units to law enforcers. Additionally, during this period, a separate category known “Special Rangers,” and later the partisan “Loyalty Rangers,” were created. These groups were not a part of the Texas Rangers organization, nor were they subject to that chain of command, despite the similarity in the designations and the fact that they possessed statewide law enforcement authority. Special Rangers were privately funded and served a wide variety of organizations, from railroad and oil companies to cattle associations, and there were typically far more Special Rangers at any given time than actual Texas Rangers. Loyalty Rangers were political partisans created and empowered under a special legislative act and specifically tasked with ferreting out alleged subversives across the state during World War I, as opposed to being general law enforcement officials. Like Special Rangers, there were far more Loyalty Rangers—three in each of Texas’s 252 counties at the time, 756 total (approximately 38 times the average number of actual Texas Rangers during that period). The common use of the term “ranger” among those distinct and separately administered groups led to confusion among both contemporary citizens and some historians regarding who should be considered to have been a “real” Texas Ranger historically and, therefore, whether actual Texas Rangers were responsible for many of the acts that have long been attributed to them.

In 1901, the Frontier Battalion was reorganized as the “Ranger Force,” though they remained a subdivision of the Adjutant General’s Department and were expected to continue to patrol and protect the border region and other sparsely settled areas. A mere three companies, often consisting of less than twenty men, were tasked with patrolling the entire state and maintaining order for millions of Texans. It proved an impossible job, and the men assigned to undertake it ranged from “highly capable to wholly unsuited,” depending on both the available leadership and the political environment at any given time. In examining Ranger history, it is crucial to note that, until 1935 and due to the vague wording of the statute that had created the Ranger Force, Texas governors sought to increase their power in this traditionally “weak governor” state by exerting direct control over the appointment of all Texas Rangers, though their motivation was rarely seen to have been in the furtherance of good government.

Beginning with Gov. Oscar B. Colquitt, many of Texas’ chief executives began to directly involve themselves in the selection not only of Ranger captains, but also of each and every Ranger on the force. More often than not, such selections were made based on the applicant’s politics, rather than their law enforcement experience. The abuse of that process degenerated exponentially and to such a degree over the first three and a half decades of the twentieth century that it finally caused a complete overhaul of state law enforcement. The practice also coincided with many of the most criticized actions in the history of the Texas Rangers, their reputation suffering greatly among the population of the state at large during that period. The effects were so pronounced by the mid-1930s that a Texas journalist quipped, “A Ranger commission and a nickel will get you . . . a cup of coffee anywhere in Texas." (At the time, during the nadir of the Great Depression, a cup of coffee only cost a nickel, on average.)

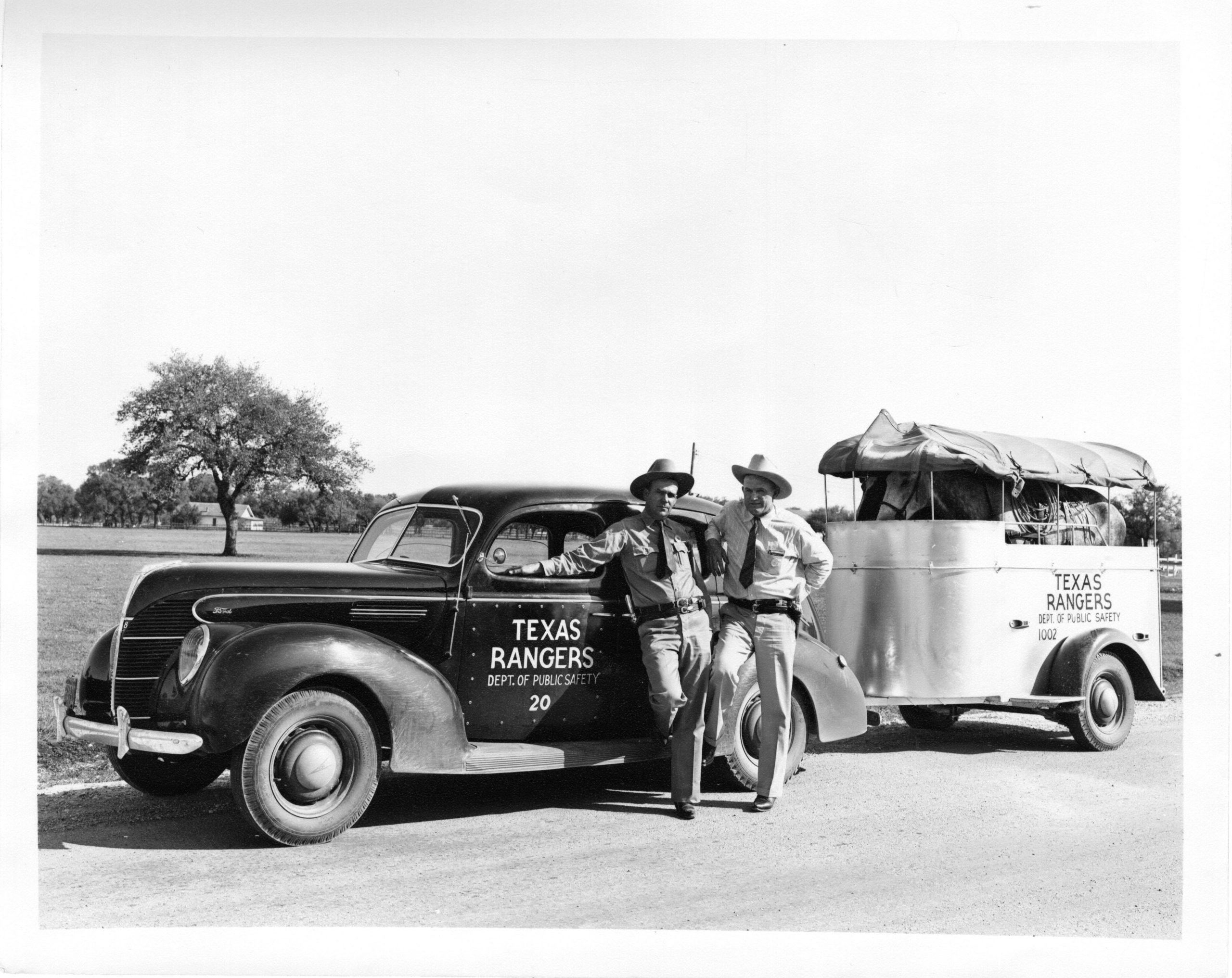

The massive overhaul of state law enforcement in 1935 was specifically undertaken as a result of the increasing politicization of the Texas Rangers during the previous three decades. From that point forward, the Texas Rangers Division of the Department of Public Safety evolved into an elite unit of internationally respected criminal investigators, focusing on major crimes such as murder and public corruption. Yet while the Rangers themselves were modernizing, their emerging historiography and the ever-expanding forms of popular media based on their tradition remained mired in myths of the past.

The breadth, depth, and longevity of the Texas Rangers mythology are remarkable. But just who, exactly, is responsible for the creation of the mystique, and the myths upon which it has been built?

The answer is a mixture of popular media, early historians, and sometimes even actual Texas Rangers, whose generally uncoordinated yet often symbiotic tales combined to form a seemingly intractable narrative in the minds of the general public, separate from historical reality. A key problem is that the first two generations of historiography dealing with the Texas Rangers was founded and relied far too heavily on what scholars often refer to as “oral traditions.” Oral traditions do have a significant role in the context of evaluating historical reality; but they are vulnerable to influence by gossip, innuendo, and personal anecdotes, magnified across multiple generations. Unfortunately, many scholars, even today, reference these sources uncritically, accepting their conclusions without first examining the validity of the information at the core of the matter or the credibility and potential bias of the source.

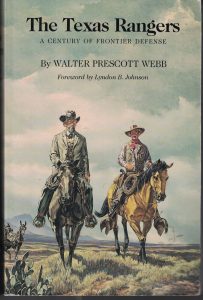

Any discussion of the historiography of the Texas Rangers in myth and memory must begin with historian Walter Prescott Webb and the extraordinary scope of his influence on the topic. The history of the Texas Rangers has long been a key component in the traditional Anglophone historiography of the American West, which relied upon the Turner Frontier Thesis to bolster Anglo-American notions of Manifest Destiny. Published during the widely-publicized Texas Centennial Celebrations, Webb immortalized the Rangers as righteous and invincible in his ethnocentric and sycophantic 1936 history, The Texas Rangers: A Century Of Frontier Defense. While it was hardly the first book to document some aspect of Texas Rangers history, Webb’s was the first scholarly publication and broad-reaching general history of the Rangers, a monumental treatise that remained unchallenged for nearly forty years. The comprehensive treatment by such an esteemed historian was accepted at the time to be beyond reproach. Furthermore, the book’s influence on both academic and popular Texas Rangers historiography, and by extension the public consciousness, is objectively impressive: after almost eighty years it is still in print and until recently, had sold more copies than any other book in the University of Texas Press catalog, several times over.

Any discussion of the historiography of the Texas Rangers in myth and memory must begin with historian Walter Prescott Webb and the extraordinary scope of his influence on the topic. The history of the Texas Rangers has long been a key component in the traditional Anglophone historiography of the American West, which relied upon the Turner Frontier Thesis to bolster Anglo-American notions of Manifest Destiny. Published during the widely-publicized Texas Centennial Celebrations, Webb immortalized the Rangers as righteous and invincible in his ethnocentric and sycophantic 1936 history, The Texas Rangers: A Century Of Frontier Defense. While it was hardly the first book to document some aspect of Texas Rangers history, Webb’s was the first scholarly publication and broad-reaching general history of the Rangers, a monumental treatise that remained unchallenged for nearly forty years. The comprehensive treatment by such an esteemed historian was accepted at the time to be beyond reproach. Furthermore, the book’s influence on both academic and popular Texas Rangers historiography, and by extension the public consciousness, is objectively impressive: after almost eighty years it is still in print and until recently, had sold more copies than any other book in the University of Texas Press catalog, several times over.

This acknowledgement of Webb’s influence is an indictment rather than an endorsement; his prominence and apparent authority led generations of scholars and authors to accept his purported facts, conclusions, and interpretations without question, thereby reproducing his errors and bias without critical examination for decades. This is particularly unfortunate in light of the fact that Webb himself had recognized the book’s shortcomings, and was working on a heavily revised edition. Due to his untimely death, however, Webb never was able to publish that revised edition correcting his earlier errors. Since then, the University of Texas Press, which obtained the copyright and began reprinting the book in 1965, has continued to publish it in its original form, without the benefit of any prologue or other disclaimer. As a result, many modern authors continue to cite Webb uncritically, thereby perpetuating a stilted and prejudiced view of the events and people involved. New generations of historical readers continue to be misled by reading this outdated and inherently flawed book, with no understanding that the author himself did not intend for it to continue to be published in that original version.

Webb set the bar for Texas Rangers historiography disappointingly low, particularly where analysis and interpretation of racial dynamics were concerned. The intervening period (between the publication of Webb’s Texas Rangers and the eventual rise of works critical of Webb decades later) saw a litany of memoirs, biographies, pictorial histories, magazine articles, juvenile books (including one by Webb), and historical fiction publications flood the marketplace. Essentially all of those cited, affirmed, or were altogether based on Webb and followed his example. An unfortunate consequence of this trend was the resulting impression within the ranks of academic historians that any studies on the topic were unlikely to produce a scholarly and objective portrayal, and that only works critical of the Rangers were likely to have any merit. The perception of Texas Rangers’ historiography as unsuited for scholarly attention still lingers among academic historians, even as numerous works taking Webb to task have appeared, due to the longevity and breadth of Webb’s influence. The modern publication of narrative, non-academic works aimed at the commercial market are primarily derivative and lacking in nuance and balance has only reinforced this notion. For that reason, they contribute to the myth and memory of the Rangers, even today.

Some of the earliest myths regarding the Texas Rangers centered around the ethnocultural centrism that was prevalent in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in Texas, which espoused notions of the inherent superiority of Anglo-European Texans over the Indians and Latinos that they were seen to have either subjugated or displaced. The authors promoting this viewpoint insisted that Anglo-Texans were nobler and more honorable than their “foes,” and that they possessed inherent military superiority as well. As the primary defenders of the frontier for the Anglo-dominated new Republic, the early Texas Rangers were glorified as an invincible and irreproachable mounted force. This was despite the fact that their record on the battlefield varied widely over time, and it was most dependent on the quality of leadership provided by the individual commanders, as well as the specialized combat experience and expertise of their chosen men.

Two of the earliest chronicles of Texas history that influenced future works through romanticized accounts of Rangers exploits were Indian Wars and Pioneers of Texas, an ethnocentric compilation of brief biographies of people the author considered to be notable Texans of the nineteenth century, and The History of Texas from 1685 to 1892, a general history of Texas, as implied by the title. Both books were written by John Henry Brown, a journalist and soldier who served in numerous ranging companies during the Republic and early statehood period, and who was intimately involved in the process of removing Indians to reservations during his career. Brown’s works are plagued by a lack of substance, an absence of documentation or source material, and a patently partisan perspective, which leads him to denigrate Indians as “savages,” and assume all Mexicans to be acting in “bad faith,” while romanticizing Anglos as universally honorable and valiant. Another example of the traditionalist narrative is James Thomas DeShields, whose writing career spanned from the 1880s until the 1940s, and who similarly eulogized Anglo historical actors as heroes while treating Indians and Tejanos as insignificant and inferior.

Two of the earliest chronicles of Texas history that influenced future works through romanticized accounts of Rangers exploits were Indian Wars and Pioneers of Texas, an ethnocentric compilation of brief biographies of people the author considered to be notable Texans of the nineteenth century, and The History of Texas from 1685 to 1892, a general history of Texas, as implied by the title. Both books were written by John Henry Brown, a journalist and soldier who served in numerous ranging companies during the Republic and early statehood period, and who was intimately involved in the process of removing Indians to reservations during his career. Brown’s works are plagued by a lack of substance, an absence of documentation or source material, and a patently partisan perspective, which leads him to denigrate Indians as “savages,” and assume all Mexicans to be acting in “bad faith,” while romanticizing Anglos as universally honorable and valiant. Another example of the traditionalist narrative is James Thomas DeShields, whose writing career spanned from the 1880s until the 1940s, and who similarly eulogized Anglo historical actors as heroes while treating Indians and Tejanos as insignificant and inferior.

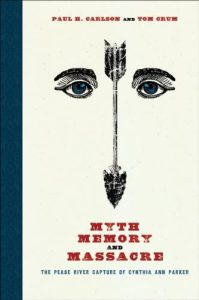

Brown, DeShields, and several generations of Texas history authors that followed them conveniently highlighted any and all victories by the Rangers, while simultaneously ignoring any defeats and dishonorable episodes, often claiming victory and glory when the facts and circumstances suggested otherwise. Perhaps the most notable event involving the latter approach was that of the famous “battle” of Pease River, which involved a contingent of Texas Rangers under the legendary Lawrence Sullivan “Sul” Ross. Ross’s fraudulent account of that event was carefully crafted and expanded in furtherance of his political career, which he capped with two terms as governor of Texas from 1887 to 1891. What has long captivated the public about an event that would otherwise have been considered a minor footnote in Rangers history is the connection to the saga of Cynthia Ann Parker and her son, Quanah—one of the last Comanche chiefs to resist the authority and western expansion of the United States. The combined involvement of the Parkers and Sul Ross “inspired an elaborate fabrication of [those] events,” and turned what was an “indiscriminate slaughter” into a “decisive battle” that was proclaimed as having “shattered Comanche military power.” Very little of Ross’s account stands up to historical scrutiny, however, and it was the accounts of his own subordinate Rangers that often contradicted his claims.

In Myth, Memory, and Massacre: The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker, Paul H. Carlson and Tom Crum challenged many of the contemporary notions of Anglo racial superiority and reveal how such notions were propped up by highlighting Indian “atrocities” at every opportunity while simultaneously ignoring or even covering up similar acts of “brutality and barbarism” by Anglo Texans, including the massacre of mostly women and children at the “battle” of Pease River. As Carlson and Crum point out, there are many “sacred” mythical accounts and interpretations of events in Texas history that have shaped the modern Texas identity, but many originated from very problematic racial interpretations, unbeknownst to the members of the general public that cling to them. Nevertheless, early ethnocentric writers were not alone in the promulgation of pro-Ranger mythology. Sometimes actual Texas Rangers have engaged in such practices, to serve their own individual and professional ends.

In Myth, Memory, and Massacre: The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker, Paul H. Carlson and Tom Crum challenged many of the contemporary notions of Anglo racial superiority and reveal how such notions were propped up by highlighting Indian “atrocities” at every opportunity while simultaneously ignoring or even covering up similar acts of “brutality and barbarism” by Anglo Texans, including the massacre of mostly women and children at the “battle” of Pease River. As Carlson and Crum point out, there are many “sacred” mythical accounts and interpretations of events in Texas history that have shaped the modern Texas identity, but many originated from very problematic racial interpretations, unbeknownst to the members of the general public that cling to them. Nevertheless, early ethnocentric writers were not alone in the promulgation of pro-Ranger mythology. Sometimes actual Texas Rangers have engaged in such practices, to serve their own individual and professional ends.

Despite the fact that they have and continue to receive such widespread media attention, most Texas Rangers have typically avoided public attention and scrutiny. However, there has always seemed to be at least one in each generation that craved the limelight.

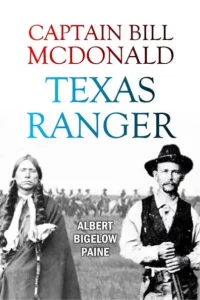

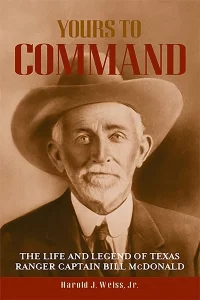

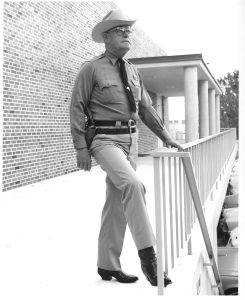

A few examples are Captain Bill McDonald of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Manuel “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullus of the mid twentieth century, and Senior Captain Clint Peoples of the mid- to late twentieth century. McDonald was perhaps best known for the motto, “No man in the wrong can stand up against a fellow that’s in the right and keeps on acomin,” and the mythical, “One Riot, One Ranger.” Gonzaullus’s biography erroneously identified him as the “first Hispanic Ranger captain,” despite the fact that he had missed that distinction by more than a century.

Peoples used his position and political contacts to situate himself as the preferred Ranger consultant for television and film in the 1960s and 70s. All three are regarded as having been effective Ranger commanders, though none were without flaw. In fact, according to Robert Utley, author of Lone Star Justice: The First Century of the Texas Rangers, it was precisely Peoples’ “mountainous ego” and questionable relationship with Hollywood that precipitated the end of his Ranger career, despite his strong political ties and relative success as a Captain.

Sometimes stories that appear to have originated with an actual Ranger eventually get exaggerated and take on a life all their own, eventually rising to the level of myth. Perhaps the best example of that phenomenon is a phrase that is often quoted as an unofficial Rangers motto (though not reflective of actual Rangers practices in the past or present).  That is the seemingly ubiquitous idiom, “One Riot, One Ranger.” The phrase appears to have originated with Ranger Captain Bill McDonald, though even his own authorized 1909 biography equivocates mightily when addressing this powerful meme of Texans’ collective memory, and fails to offer pertinent historic details in its mere three-sentence account. Nevertheless, articles have appeared in books and newspapers around the country carrying versions of the story and purporting it to be true.

That is the seemingly ubiquitous idiom, “One Riot, One Ranger.” The phrase appears to have originated with Ranger Captain Bill McDonald, though even his own authorized 1909 biography equivocates mightily when addressing this powerful meme of Texans’ collective memory, and fails to offer pertinent historic details in its mere three-sentence account. Nevertheless, articles have appeared in books and newspapers around the country carrying versions of the story and purporting it to be true.

The earliest publication found expounding a detailed version of the event is the book Riding For Texas: The True Adventures of Captain Bill McDonald . . . As told by Colonel Edward M. House to Tyler Mason, published in 1936. The Author’s Notes in the book offer this equivocating disclaimer: This is not a biography — Albert Bigelow Paine’s admirable “Life of Captain Bill McDonald” filled that need a quarter of a century ago — and the accuracy of an historical record is not to be sought in these pages.  We have aimed at color and drama more moving than the rigid limitations of biographical exactitude would have permitted. The deeds performed by Captain Bill owe nothing to the imagination. Each story is founded on an actual true adventure; the subsidiary characters and background have been so combined as to throw the chief actor into sharp relief, but care has been taken to avoid over-statement and false heroics. We have tried to re-create a character whose life was the very stuff of which fiction is made. The account by Mason and House provides enough detail to recognize it as related to historic events, but names are changed, details such as exact locations and dates are omitted, and the interactions between McDonald and the un-named mayor of the un- named town are not to be found in any historical records or publications.

We have aimed at color and drama more moving than the rigid limitations of biographical exactitude would have permitted. The deeds performed by Captain Bill owe nothing to the imagination. Each story is founded on an actual true adventure; the subsidiary characters and background have been so combined as to throw the chief actor into sharp relief, but care has been taken to avoid over-statement and false heroics. We have tried to re-create a character whose life was the very stuff of which fiction is made. The account by Mason and House provides enough detail to recognize it as related to historic events, but names are changed, details such as exact locations and dates are omitted, and the interactions between McDonald and the un-named mayor of the un- named town are not to be found in any historical records or publications.

The irony is that not only was McDonald not alone when Governor Culberson sent the Rangers to stop a prize fight from happening in El Paso in 1896 (the only such historical incident), but the entire Ranger force was there with him. All four of the so-called “Great Captains” (Brooks, Rogers, Hughes, and McDonald) and their companies were present, the only time in history that ever occurred. Walter Webb hedged on the issue, saying that there was “some basis for the story,” yet he also pointed out its dubious nature, noting that McDonald’s Ranger contemporaries would laugh whenever they heard it. He also lamented that, “It seems to be the only story that the public remembers about the Rangers.” Robert Utley referred to the alleged event as an “enduring legend” that originated from McDonald’s use of “theatrics,” and the modern biography of McDonald—published in 2009 by Harold Weiss—thoroughly and effectively commits the story to its final resting place in the land of fables.

The irony is that not only was McDonald not alone when Governor Culberson sent the Rangers to stop a prize fight from happening in El Paso in 1896 (the only such historical incident), but the entire Ranger force was there with him. All four of the so-called “Great Captains” (Brooks, Rogers, Hughes, and McDonald) and their companies were present, the only time in history that ever occurred. Walter Webb hedged on the issue, saying that there was “some basis for the story,” yet he also pointed out its dubious nature, noting that McDonald’s Ranger contemporaries would laugh whenever they heard it. He also lamented that, “It seems to be the only story that the public remembers about the Rangers.” Robert Utley referred to the alleged event as an “enduring legend” that originated from McDonald’s use of “theatrics,” and the modern biography of McDonald—published in 2009 by Harold Weiss—thoroughly and effectively commits the story to its final resting place in the land of fables.

An interesting gauge of the impact of this mythological creed spawned by the fertile imaginations of Mason and House can be found in the archives of the Los Angeles Times. There you will find that the “One Riot, One Ranger” myth has become so engrained into the national psyche that the Los Angeles Police Department has been chastised for not living up to this fictional standard. An Op Ed article in the Los Angeles Times dated July 25, 1949, invoked the famous phrase and the perceived Texas Rangers standard as a way to encourage the LAPD to eliminate two-man patrol units to provide what the writer considered to be more judicious use of police manpower. A December 31, 1932, Los Angeles Times article also invokes the legendary “quote” while comparing the United States Marines to the venerated Texas organization, calling them “Uncle Sam’s Rangers” (an ironic reference considering that the United States Army actually has always had a division officially designated as “Rangers” who, though famous in their own right, are still not as widely venerated as the Texas variety). Finally, an October 4, 1931 Los Angeles Times article issued a call for the “Texas Ranger Spirit” while trying to encourage local, state, and federal authorities not to shy away from their duty to bring dangerous organized crime figures (such as Al Capone) to justice. Incidentally, Texas Rangers of that era were known to brag about their relative success in limiting organized crime operations in the Lone Star State.

Arguably, the most common method Rangers have used to perpetuate the myth surrounding them is simply ignoring or concealing the shortcomings or misdeeds of their predecessors and colleagues. That practice is most evident in regard to Texas Rangers in pursuit of Mexican bandits and revolutionaries from approximately 1910 to 1919. Rangers actions during that period resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Latinos, some of whom may have been loyal Tejanos and likely innocent of any real malfeasance. The result of those alleged abuses on the Rangers’ reputation in South Texas was aptly characterized by something that former Ranger Ray Martinez was told after being assigned there in the 1970s: “Every Texas Ranger has Mexican blood . . . on the tips of his boots.” The motivations of later Rangers and media sources for such treatment cannot be entirely known, but some may have felt that the acknowledgement of shortcomings would undermine their effectiveness, while other may have sincerely believed the acts in question were justified.

The comments and responses from numerous modern Rangers interviewed for the April 2007 Texas Monthly article “These Are Not Your Father’s Texas Rangers“ however, would seem to indicate that method of handling controversial subjects (among others) is no longer prevalent. Frank and critical commentary on Ranger actions during the 1967 Rio Grande Valley United Farm Worker’s Strike, made on camera by the late Captain John Wood and other modern Rangers, also signifies that their approach to addressing the foibles of fellow Rangers has evolved. And while it is true that some Rangers and their adherents have, at times, propagated myths to their own benefit, it is also important to note that there are arguably as many anti-Ranger counter-myths. Many of such myths are so prevalent and accepted in popular memory and by some academic historians that, as Robert M. Utley acknowledged in his preface to Lone Star Lawmen, he began his research expecting to find evidence of institutionalized racial bias among the Texas Rangers against Tejanos. It was a notion that, much to his surprise, was not born out by the historical record and instead proved to be based on numerous historical fallacies.

Regardless of justification or intent, there has been tension between many Tejanos from South Texas and the Texas Rangers for generations. But the historical record does not support simplistic “Anglo versus Hispanic” narratives in regard to these issues, and some Tejano/Latin American historians have fallen victim to the same stereotyping employed by many of the dueling traditionalist narratives. One of the issues driving conflict between South Texas Tejanos and the Rangers was the organization’s diverse responsibilities during that period, most particularly defense of the United States–Mexico Border in Texas (a unique role for a state constabulary, and one that has recently been reinstated in the modern era). Historically such duties led to direct conflict with many Rio Grande Valley Tejanos, many of whom were often engaged in supporting Mexican exiles and filibustering activities after Mexico declared its independence from Spain, especially since opposition to the Porfirio Diaz regime began to build in the latter nineteenth century. Rangers interference in these illegal but locally popular activities often biased the South Texas perspective on the Rangers efforts and actions.

Furthermore, historian Robert M. Utley closely examined the relationship between Valley Tejanos and Rangers, thereby shining a scholarly light on the mythology of both groups. A primary example of what Utley refers to as the “stereotype[ing]” of Texas Rangers is how they have been accused as being willing conspirators and enforcers in the dispossession of Tejanos from their rightful lands, mainly in the region known as the Nueces Strip, which is situated along the border with Mexico. This perception appears to be a result of Texas Rangers involvement in the suppression of the “Cordova Rebellion” in 1838-39, the “Cortina War” in the late nineteenth century, and their response to the threatened “Plan De San Diego” in early 1915. The story begins with Vincente Cordova of Nacogdoches, a Tejano leader in East Texas who had been an Anglo ally in the fight to restore the federalist Constitution of 1824, which Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna declared invalid (despite having been elected on the federalist platform). Considering himself a loyal and patriotic Mexican citizen, Cordova would not support the eventual independence movement and thereafter acted as a filibuster in Texas on behalf of the Mexican Government. After the Texas won its independence, Cordova led a revolt in 1838-1839 involving an attempted alliance with the Cherokees with the intention of returning Texas to Mexico. He was killed in the Battle of Salado Creek on September 18, 1842, though his descendants still live throughout the state.

Following in Cordova’s footsteps, Juan Nepomuceno Cortina fomented violence and rebellion under the guise of advocating for justice for displaced Tejanos. There is evidence, however, his actions were more likely motivated by the loss of the U.S.–Mexican War, which served as a pretext for the commission of otherwise unrelated crimes. The 1915 Plan De San Diego “sought to reclaim territory taken by the United States from Mexico in 1848 [pursuant to the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe] restore ancestral lands to indigenous people [it was unclear how conflicting Spanish/Mexican and Native claims would be dealt with] create an independent republic for Latinos, and kill every Anglo male over the age of sixteen.” Despite having signed treaties relinquishing their claims to Texas after both the Texas revolt and the U.S.–Mexican War, the Mexican Government was continually engaged in filibustering activities well into the twentieth century, thereby stoking intrigue and inflaming passions in the border region for close to a century after Texas first gained its independence from Mexico. It is that arguable that such efforts contributed—more than any other single factor—to the conflicts between the Texas Rangers and South Texas Tejanos, at least some of whom maintained allegiance with their mother country and assisted its efforts at undermining Texas’ sovereignty.

As defenders of the Republic and later state of Texas, the Rangers had a lawful responsibility to respond to each of these perceived threats to Texas’ sovereignty, regardless of the ethnicity of those involved. And while there are certain anecdotal historical incidents involving specific alleged bad acts by specific Texas Rangers—which have been repeated over and over by various historians and other critics—the historical record simply does not contain sufficient evidence to indicate that the Texas Rangers’ actions overall, in furtherance of their lawful duties, were motivated by either racial hostility or a concerted plan to effect dispossession of Tejanos. Nor is there any evidence of the widespread displacement claimed or other adverse treatment by actual Texas Rangers. Examination of critical claims through the prism of the historical record reveals the inadequacy of simplistic “Anglo versus Hispanic” narratives in regard to these issues, or for the interpretation of Texas and US-Mexico border history, generally.

In addition to such nuanced topics of historical debate, the Texas Rangers have also, at times, been blamed for acts that they simply did not commit. Perhaps the most notable example is that of the Gregorio Cortez episode. Cortez was the subject of a Mexican corrido, or fable, which was made famous by the late folklorist and University of Texas professor of literature, Americo Paredes. Cortez was accused of killing a law enforcement officer and successfully evaded sheriff’s posses for months. According to contemporary news accounts and widespread public perception in South Texas, the Rangers killed Cortez. But in fact, the Rangers joined the search for Cortez much later and captured him quickly and peacefully, then protected him from lynch mobs during his trials. Another example is that of Mexican Revolutionary General Pascual Orozco, who was a federal fugitive indicted for violations of United States Neutrality laws. Contrary to a contemporary New York Times account claiming he had been “rangered,” Cortez was actually killed in a shoot-out with a local civilian posse from El Paso, after he and his men allegedly opened fire on their pursuers. But the deaths of both men, in a persistent myth promulgated not only by some South Texas Tejanos but also by modern historians, are often still ascribed to the Rangers.

Furthermore, Utley determined that evidence regarding specific “evaporations”—an historic regional colloquialism for alleged summary executions—might be considered sparse and ambiguous, at best. The relative thinness of their ranks during this period also casts doubt on some of the claims of widespread misdeeds by actual Texas Rangers during this period, particularly since it has since been shown that numerous incidents originally attributed to the Rangers were in fact unconnected to actual Texas Rangers; many involved instead either Special or Loyalty Rangers as well as local and even federal lawmen in the region, if not others wholly unconnected to law enforcement, such as local ranch hands or private security agents.

One reason for widespread errors of fact in this area is language misinterpretations. This has led some historians and others unfamiliar with the nuances of border region Tejano terminology to conflate allegations by Tejanos against Rangers with allegations against other lawmen who also operated in the Rio Grande Valley. As Utley noted, many different types of “Rangers” existed during that era, many created expressly for partisan purposes and operating independently of the formal institution’s command structure. Furthermore, there were countless federal and local law enforcement officers working in the Rio Grande Valley, and the South Texas derogatory term, “rinches,” was a reference to any Anglo authority figure in the region on a horse, wearing a badge, hat, and gun. It is accurate to say that South Texas Tejanos often refer[red] to Rangers as “rinches,” but the term did not apply to them exclusively, as so many modern scholars have asserted. As Americo Paredes pointed out, it was a term that—at a minimum—applied to all lawmen who operated in the Rio Grande Valley, whether local, state, or federal, and possibly even without regard to their individual ethnicity.

Recent research into sources originating out of northern Mexico indicates that the term may actually have originated as an amalgamation of “pinches rancheros,” (Translation: damn ranchers) a fact that further vitiates any singular or exclusive connection to the Texas Rangers.

According to that source, Mexican tequileros (smugglers), revolutionaries, and other Mexican nationals who sought to cross into the United States for unlawful purposes used the phrase to refer to the cowboys and ranch security personnel who frequently prevented their crossing private lands north of the Rio Grande in pursuit of their illicit activities. As a result of such linguistic confusion over time, and the accompanying uncritical assumptions on the topic made by many modern scholars, at times Rangers have likely been blamed for acts committed by entirely different law enforcement organizations, or perhaps even by non-law enforcement historical actors. Furthermore, few scholars or other Texas Rangers historians have studied that period thoroughly enough to understand the processes of their evolution from frontier defenders into law enforcement, or to fully evaluate the effect of politics on their quality and reputation. That oversight has often led critics of the Texas Rangers to apply unrealistic expectations to Rangers of this and even earlier periods, particularly when assessing their actions in accordance with standards of modern law enforcement officers. It is obviously unreasonable to analyze the actions of nineteenth-century citizen-soldiers or early twentieth-century political appointees based on professional law enforcement standards that first began to evolve in 1935.

One of the most perplexing myths involving Tejanos and Texas Rangers, perpetuated by both traditionalists and early revisionists, is the notion that there were no Tejano Rangers until the latter twentieth century. In addition to Utley’s two-volume institutional history of the Rangers, Lone Star Justice and Lone Star Lawmen, Stephen Moore’s Savage Frontier series thoroughly documents that Tejanos (as well as American Indians) have served as Rangers and Ranger captains since the days of the legendary Captain Jack Hays. Two notable examples are Antonio Perez and Salvador Flores (the latter a brother-in-law to famous Texas patriot, Juan Seguin, whom both had served under in Mexican colonial era flying squadrons). Additionally, it was an all-Tejano company under Captain Cesario Falcón that originally cultivated the Ranger’s close, lasting, and often criticized relationship with the legendary King Ranch.

One of the most perplexing myths involving Tejanos and Texas Rangers, perpetuated by both traditionalists and early revisionists, is the notion that there were no Tejano Rangers until the latter twentieth century. In addition to Utley’s two-volume institutional history of the Rangers, Lone Star Justice and Lone Star Lawmen, Stephen Moore’s Savage Frontier series thoroughly documents that Tejanos (as well as American Indians) have served as Rangers and Ranger captains since the days of the legendary Captain Jack Hays. Two notable examples are Antonio Perez and Salvador Flores (the latter a brother-in-law to famous Texas patriot, Juan Seguin, whom both had served under in Mexican colonial era flying squadrons). Additionally, it was an all-Tejano company under Captain Cesario Falcón that originally cultivated the Ranger’s close, lasting, and often criticized relationship with the legendary King Ranch.  Nevertheless, traditionalist Anglo-phone interpretations of Texas were often crafted to aid in the political oppression and disenfranchisement of Hispanic Texans from the late nineteenth to well into the twentieth century. In response, later twentieth century Chicano and other related revisionist interpretations reacted to the ethnocentrism of the Anglo narratives by simply arguing that it was their group that possessed the moral high ground, but otherwise relying on the same basic Anglo-Latino culture conflict interpretive model originally concocted by the Anglo traditionalists, which inevitably led the early revisionists to also ignore the service and contributions of Tejano Rangers. As a result, both have unjustifiably denied Tejanos’ agency in the creation and development of modern Texas, despite overwhelming historical evidence to the contrary.

Nevertheless, traditionalist Anglo-phone interpretations of Texas were often crafted to aid in the political oppression and disenfranchisement of Hispanic Texans from the late nineteenth to well into the twentieth century. In response, later twentieth century Chicano and other related revisionist interpretations reacted to the ethnocentrism of the Anglo narratives by simply arguing that it was their group that possessed the moral high ground, but otherwise relying on the same basic Anglo-Latino culture conflict interpretive model originally concocted by the Anglo traditionalists, which inevitably led the early revisionists to also ignore the service and contributions of Tejano Rangers. As a result, both have unjustifiably denied Tejanos’ agency in the creation and development of modern Texas, despite overwhelming historical evidence to the contrary.

As Robert Utley’s emphasis on the significance of the creation of the Texas Department of Public Safety in 1935 as a pivotal moment in their evolution from frontier fighters into modern lawmen demonstrated, an accurate evaluation of Ranger history requires a nuanced consideration of different times, places, administrations, commanders, individual Rangers, and other factors, which cannot be fully tested without a thorough examination of the second century of Texas Rangers history. To date, few studies or biographies have been written on the Department of Public Safety Texas Rangers of the modern era, other than Utley’s Lone Star Lawmen, thereby creating an unfortunate gap in the historiography that leaves even the most astute history aficionado with an outdated perspective on the still active and internationally renowned force.

None of this is to say that all Texas Rangers throughout history were innocent of any particular charges of abuse by Tejanos, or by others for that matter. On the contrary, the point is simply that such allegations should be held up to the same scrutiny, as are the assertions of the Anglo-centric traditionalists like Webb and other apologists. And perhaps most importantly, even more care should be taken when using such anecdotal evidence in an attempt to extrapolate through interpretive analysis and apply such judgments to the entire force, and over time.

Essentially, the leveling of sweeping indictments or sweeping endorsements to those who served as Texas Rangers across the state and over the past nearly two centuries is no more historically valid than any similar ethnic-based stereotype, be they based in Anglo notions of Manifest Destiny, or the counter-narratives of historically marginalized groups. Fortunately, many modern scholars now seek to promulgate a more inclusive interpretation of historical events, one that eschews stereotypes of any group across time and place, and which acknowledges the actions and involvement of all historical actors without regard to ethnicity or any other categorization. However, and despite such efforts on the part of academic historians, popular media has long perpetuated a simplistic characterization of Texas Rangers history in our collective memory. Unfortunately, such practices have not evolved in concert with that of the academic historical community. The result is that the majority of the population is still bombarded with a long outdated and one-sided view of that history which, in turn, reinforces ill feeling among many Valley Tejanos and Latin American historians.

While partisan perspectives have certainly contributed to the continuing dissemination of misinformation on the topic, the history of the Texas Rangers has been shrouded in myth and legend in the collective consciousness almost since their origins in the Mexican colonial era, and popular news and entertainment media have been the most prolific propagators of that simplistic and narrowly tailored legend. Public perception has been shaped, for the most part, by deliberately manipulated interpretations orchestrated by a wide variety of popular media outlets.

In each case, historical fact was often sacrificed in favor of varying degrees of fiction that served a variety of purposes, be they political agendas, personal vanity or, most commonly, the desire for one-dimensional entertainment. Long fascinated with the history of the Texas Rangers, popular media’s effect on the collective memory of the populace has been exponentially more influential than that of all Texas Rangers historians combined. Since they came to international notice during the United States–Mexican War, every form of popular media has used a variety of sources to promulgate and propagate a hybrid pioneer-patriot archetype of the quintessential Texas Ranger. As evidenced by the proliferation of novels, newspaper and magazine articles, radio serials, silent films, television series, and modern feature films, Rangers lore has consistently found a solid following.  Historian Bill O’Neal’s 2008 publication, Reel Rangers, documents the vastness of the genre in television, radio, and film: For nearly a century the world’s most famous law enforcement body has inspired novelists, actors and filmmakers. . . From The Lone Ranger to Walker, Texas Ranger,

Historian Bill O’Neal’s 2008 publication, Reel Rangers, documents the vastness of the genre in television, radio, and film: For nearly a century the world’s most famous law enforcement body has inspired novelists, actors and filmmakers. . . From The Lone Ranger to Walker, Texas Ranger,

from Zane Grey’s The Lone Star Ranger to Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, Texas Rangers have been portrayed on the silver screen, network radio and television. John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Tom Mix, Clint Eastwood, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, and a host of lesser Western stars each took his turn at depicting Texas Rangers. … And Hollywood’s preoccupation with the Texas Rangers has not waned even in the slightest since O’Neal completed his study, as Texas Rangers stories, characters, and references continue to be found in even the most recent popular programming.

A few examples are: the popular remake Hawaii 5-O featured a (ludicrous depiction of a) Texas Ranger in an 2013 episode; a short-lived ABC series—for which only the pilot ever aired—titled, Killer Women, featuring a modern female Ranger as the lead character; the History Channel has produced a fictional mini-series titled Texas Rising, which centers around the Texas Rangers of the Republic era from 1836 to 1846 and claims to tell “the story of how the Texas Rangers were created,” and which is scheduled to be released in 2015; and an independent film written, produced and directed by Robert Duvall, and featuring his wife as a modern Texas Ranger in the lead role, which just completed principle photography and will likely be released in late 2015. Even a recent episode of Justified, a highly rated television series on the FX Channel now in its sixth season, referenced the mystique of Texas Rangers in its 2015 season premiere. In a scene between the lead character, a U.S. Marshal, and a Mexican Federal Police Officer (Federales), the Federal scoffs when the Marshal displays his badge, telling him, “Look around you, cabrón, this is Mexíco, and that star you wear don’t mean [expletive deleted] here! Now, a Ranger badge … that means something. They bang it out of a 1948 Mexican silver coin.”  And finally, Former Texas Ranger Joaquin Jackson’s two-volume memoir has eclipsed Webb’s Texas Rangers as it has sold well over one hundred thousand copies, spawned numerous television and motion picture appearances, and built personal relationships for Jackson with some of modern Hollywood’s biggest stars and directors. So, even after a more than century of motion picture productions and quantum leaps in the technology behind the industry, Hollywood’s fascination with the mystique of the Texas Rangers is as fresh as ever. Unfortunately, that means we will likely continue to see the proliferation of a one-dimensional and prejudicial portrayal of the Texas Rangers to yet another generation of Americans, and of the world.

And finally, Former Texas Ranger Joaquin Jackson’s two-volume memoir has eclipsed Webb’s Texas Rangers as it has sold well over one hundred thousand copies, spawned numerous television and motion picture appearances, and built personal relationships for Jackson with some of modern Hollywood’s biggest stars and directors. So, even after a more than century of motion picture productions and quantum leaps in the technology behind the industry, Hollywood’s fascination with the mystique of the Texas Rangers is as fresh as ever. Unfortunately, that means we will likely continue to see the proliferation of a one-dimensional and prejudicial portrayal of the Texas Rangers to yet another generation of Americans, and of the world.

O’Neal revealed just how deeply the popular media image of the Texas Ranger is ingrained in the American psyche by explaining that virtually every day at the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco, museum staff members have to tell patrons that Walker, Texas Ranger (Chuck Norris), Gus McCrae (Robert Duvall), and Woodrow F. Call (Tommy Lee Jones) were fictional characters and not historic Rangers. No doubt they and similar institutions, including the Texas Rangers Heritage Center currently being developed in Fredericksburg, will soon be addressing similar issues in regard to the more recent Hollywood creations. In addition to this anecdotal evidence, a 2009 scientific study done at Duke University found that people tend to subconsciously internalize information gleaned from television and movies far more quickly and intensely than from reading, making it difficult for them to separate fact from fiction—regardless of their exposure to more reliable written sources. This explains much about the creation of memory. Even those given forewarning that the book was the legitimate source and that the film was fictionalized not only provided the incorrect answers to the historical questions, but also argued that they were referencing the book when citing the erroneous information. This only supports the argument that feature films and television programs have been the main drivers in establishing and shaping the public’s decidedly inaccurate perception of the Texas Rangers.

The proliferation of the Texas Ranger legend is not limited to the entertainment media, although the following examples are in all likelihood attempts to capitalize on the marketing prowess of the Texas Rangers international brand. Their legacy is invoked in the naming of professional sports teams (the professional baseball team, 2011 World Series contenders, the former pro polo team that swept every major title in England in 1939) and a litany of commercial products and businesses (Ford Ranger trucks, Ranger Boats, and the Texas Ranger Motel in Santa Anna, Texas, just to name a few). There is even a town in East Texas is named for them. Additionally, statues of Texas Rangers adorn sites throughout the state, from the “One Riot, One Ranger” inscribed bronze statue at Dallas’s Love Field to the life-sized bronze statue of Capt. John C. Hays mounted on his horse on the courthouse square in his namesake county south of Austin.

In sum, the Texas Rangers’ influence on popular culture is virtually ubiquitous, and that culture has heavily influenced the collective memory of the Lone Star State, those interested in its history, and the Rangers themselves.

One key aspect of Ranger mystique is its sheer power and cultural reach. Sometimes this manifests as a desire to join the ranks of the Rangers. Most retired and current Rangers have stories about the first time they ever saw a Ranger and how the experience inspired them for the future. However, it is also common for men who never actually served as Rangers to claim that they had. Unfulfilled aspirations of Ranger service have been revealed in countless obituaries, like that of a Houston-area judge that claimed he was the legendary Captain Frank Hamer’s driver when Hamer tracked down and killed Bonnie and Clyde. (Hamer never mentioned this man in his records and never had a “driver,” and all those present at the ambush of Bonnie and Clyde were photographed and otherwise well-documented.) But this is not merely a Texas phenomenon.

Self-declared Texas Rangers can be found nationwide, as evidenced by a Los Angeles Times article about a would-be pick-pocket victim who slashed the hand of the suspect with a pocket knife in 1943,a 1938 L.A. Times obituary for the judge who presided over the famous Owens Valley vs. Los Angeles water rights trial, and another Los Angeles Times obituary from 1933 for the county Chief Deputy Sheriff there. In a 1920 article, a Portland man named Jack London (not the author) was proclaimed a hero for saving several people from a building fire; and he also laid claim to previous service in the Texas Rangers. Official records at the Texas State Library and Archives in Austin do not back up any of those claims, but this did not dissuade such individuals from seeking to join the ranks of the Rangers at least in newsprint.

The influence of Texas Rangers lore is not limited to North America, but rather it crosses the both oceans and spans the globe. The misplaced fears of the Nazis and Vichy French in World War II demonstrate the Ranger mystique prevalence across Europe. News of an allied raid at Dieppe that was reputed to include American “rangers” was the source of their fears because, according to the article, “To many Frenchmen there is only one type of Ranger – the Texas variety.” Nazi Germany also experienced similar fears of Texas Ranger infiltration during the D-Day Invasion. Their mystique has even traveled to Japan, where Texas Ranger books and a television show were staples in the childhood of Toyota executive T.J. Tashima. After being assigned to open the Toyota manufacturing plant in San Antonio, Texas, Tashima was able to fulfill his childhood dream of meeting real-life Texas Rangers. Japan’s reverence for their ancient samurai culture, another mounted frontier defense force, may explain their affinity for the Texas Rangers. Such widespread attraction to the Texas Rangers mystique is not merely a pop-culture phenomenon, however: it has practical implications for actual modern Rangers in the performance of their duties.

As the Texas Rangers evolved from their origins as loosely organized mounted militia units in the early nineteenth century into a professional elite investigative force by the beginning of the twenty-first century, they have been helped and hindered by the myths surrounding their forebears, despite sharing little more in common than a name. The continuing myth surrounding their name actually assists modern Texas Rangers in their modern pursuit of law and order, and thus contributes to their success. In some situations, myth and memory can convince both criminals and law-abiding citizens to offer a level of deference and cooperation to Texas Rangers that is often not extended to other law enforcement agencies.  An example of this can be found in One Ranger Returns, Joaquin Jackson’s second volume of his best-selling memoir of his time as a Ranger. Jackson relates an episode where a rancher refused to give a local sheriff access to his land but subsequently allowed Ranger Jackson access because of his mistaken belief that the Texas Ranger possessed more law enforcement authority than the sheriff. It was simply not the case legally, but the fact that the rancher believed it to be so directly influenced his decision to cooperate with the Ranger after having refused to do so with the sheriff.

An example of this can be found in One Ranger Returns, Joaquin Jackson’s second volume of his best-selling memoir of his time as a Ranger. Jackson relates an episode where a rancher refused to give a local sheriff access to his land but subsequently allowed Ranger Jackson access because of his mistaken belief that the Texas Ranger possessed more law enforcement authority than the sheriff. It was simply not the case legally, but the fact that the rancher believed it to be so directly influenced his decision to cooperate with the Ranger after having refused to do so with the sheriff.

These anecdotes give rise to the question of whether aspects of the Texas Rangers myth are so entrenched that it has become a self-fulfilling prophecy, responsible at least in part for some of their most notable successes. Examples include bringing the 1997 Davis Mountains stand-off (by well-armed “Republic of Texas” anti-government separatists) to a non-violent conclusion, successfully investigating the 2007 Texas Youth Commission corruption and abuse cases after local officials failed to do so, and obtaining the surrender and confession of the infamous late 1990’s “Railway Killer.” One of the most notable is their negotiation of a peaceful surrender agreement with the David Koresh, leader of the Branch Davidians—an arrangement unfortunately rejected by the FBI, with disastrous and deadly consequences. In these situations, the aspects of the mystique that cast Rangers as fair but relentless may have contributed to those outcomes. Modern Rangers must also contend, however, with the other side of their myth and memory, which bears resentment based on past Rangers’ misdeeds, both real and illusory. This is particularly true for a substantial segment of the Tejano population, especially in the South Texas border region, that perceives the Rangers as racially motivated oppressors serving the Anglo-dominated political establishment. The truth of the matter, as is so often the case with history and memory, lies somewhere in between the two extremes of the realm of myths.

In closing, it has been shown that while various individual Rangers have, at times, created and promulgated particular mythological anecdotes towards various personal or professional ends, such instances are exceptions and not the rule. Far more often, the myth and memory of the Texas Rangers has been perpetuated through the media, both popular and historical. Unfortunately, even the ostensibly historical treatments have often been lacking in depth, nuance, and, at times, basic factual accuracy. Furthermore, those myths are not relegated to esoteric academic debates, as modern Rangers both benefit from and suffer the ill effects of the myths in the performance of their official duties.

Fortunately, and thanks at least in part to Utley’s prompting, many scholars are now providing a more inclusive and balanced image of the Texas Rangers by moving beyond the romanticized and racially divisive rhetoric that has plagued much of Texas Rangers historiography, thereby pushing it into a new era. These historians are including an examination of the perspectives of people and communities among whom the Rangers have served and are beginning to delve into the second century of their existence, a long overdue necessity for providing a well-rounded understanding of the overall history of this nearly two hundred year old institution. Unfortunately, and as the 2009 Duke study demonstrated, academic publications are only a small part of the equation. Unless and until popular media depictions of the Rangers begin to reflect this approach, our collective memory and group identity will remain mired in the myths and legends of the past. The latest effort by the cable network History certainly does not bode well for such prospects, although and perplexingly, the companion book to that series was more promising.