If bush poet author of “The Man From Snowy River” Banjo Paterson were alive today, he’d be a star at cowboy poetry gatherings from Elko to Australia.

Paralleling America’s two-decade-long period we call the Wild West, Andrew Barton “Banjo” Paterson wrote of a wild Australia that no longer exists — if, in fact, it ever did. Nonetheless, today’s readers of his verse derive as much delight from The Banjo’s lines, as did those reading them for the first time a century ago. His anthologies are still read, biographies tracing his life are still being written, and star-studded films convert his poems from eight-stanza ballads into two-hour entertainments.

One of his many biographers referred to Paterson as the “finest balladist in the Australian idiom.” Given the proliferation of down-under “bush poets” of the late 19th/early 20th centuries, it is an ambitious — but quite possibly, accurate — claim. He is certainly one of Australia’s most celebrated poets, and among its most prolific.

A.B. Paterson lived a life as exciting as any he framed in verse. As a young man, he was a highly respected war correspondent during the Boer War, and a combat officer in World War I while in his 50s. But it was as a writer of “bush poetry” romanticizing the life and colorful characters of rural Australia that he achieved renown. Today, he is best remembered, and most eulogized, for two of his ballads: “The Man From Snowy River” and Australia’s unofficial national anthem, “Waltzing Matilda.”

Born in rural Narrambla, New South Wales, in early 1864, Paterson spent his first years on two sheep stations (ranches) of his father, an immigrant Scots stockman. The region was populated with teamsters and drovers, many of whom were superb horsemen. These “knights of the outback” and their half-wild horses made an impression on Paterson: He would later become a master equestrian himself and find inspiration in those men for many of his most popular poems.

Paterson’s father sent him to Sydney for his education, where, according to one biographer, “he traded his moleskin pants and hobnailed boots for fine city clothes.” After graduating at 16, young “Barty” took a position clerking at a city law firm.

Having acquired a family appreciation for poetry, he also began writing verse. In 1885, his work attracted the attention of The Bulletin. The fiercely nationalistic newspaper was fast becoming Australia’s foremost creative outlet for the “utopian idealists and the sentimental realists … writing at the end of the century.” It stressed the themes of national pride and traditional values, and as events would soon prove, Paterson was a perfect fit.

The Bulletin was the first to publish one of his poems, “El Mahdi to the Australian Troops.” Far from the rural themes for which he would become famous, the young poet condemns Australia’s current involvement in Britain’s war in the Sudan, shaming his country for leaving her “land of liberty and law / To flesh her maiden sword in this unholy war.” Given its incendiary nature, Paterson published the poem anonymously. However, he soon began signing his work with the pseudonym “The Banjo,” after a racehorse his family owned in his youth. This was not an uncommon practice: One of Paterson’s fellow bush poets, the roguish, romantic Harry Harbord Morant, signed his verses “The Breaker,” for his ability to saddle-break wild horses.

Paterson was admitted to the bar at 22. The young solicitor was socially popular; a talented sportsman, he enjoyed tennis and rowing, but it was on horseback that he excelled, as one of the region’s best polo players and “flat and jumps” jockeys.

Apparently, he also cut a striking figure. Decades later, an old acquaintance remembered him as “a tall man with a finely built, muscular body, moving with the ease of perfectly coordinated reflexes. Black hair, dark eyes, a long, finely articulated nose, an ironic mouth, a dark pigmentation of the skin … His eyes, as eyes must be, were his most distinctive feature, slightly hooded, with a glance that looked beyond one as he talked.”

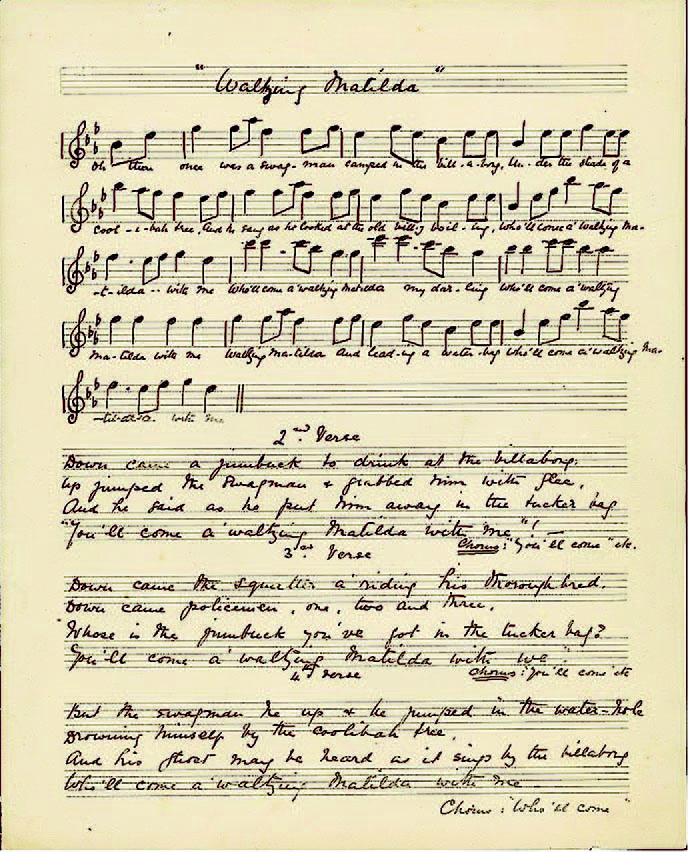

Christina Macpherson used to play the traditional tune that would become the Australian bush ballad “Waltzing Matilda” on her zither; Banjo Paterson wrote the lyrics while staying at Dagworth Station, a sheep and cattle station in Queensland owned by the Macpherson family.

It was while still practicing law that “The Banjo” penned what would become his most famous work. Interestingly, the ballad was not birthed without the salacious whiff of scandal. In the summer of 1895, Paterson visited his fiancée, Sarah Riley, at Dagworth Station, the family home of Sarah’s best friend, Christina Macpherson. During Paterson’s stay, Christina’s brother Robert, a prominent sheep rancher (“squatter”) in the area, reputedly told him the quaint tale of a transient laborer (“swagman”) who, while carrying his pack (“waltzing Matilda”), stole a sheep (“jumbuck”), and rather than submit to arrest, drowned himself in a watering hole (“billabong”).

Paterson was enthralled with the story, and he and Christina collaborated on a ballad. He wrote the words, behind which she reputedly played an old Scottish folk tune, “Thou Bonnie Wood of Craigielea,” on a zither. The result was the first version of the sad, funny, haunting “Waltzing Matilda.”

According to oral tradition, their collaboration produced another, less positive outcome. There are indications of a dalliance, or at the very least, a flirtation, between the two artists. What is certain is that Sarah returned home alone, calling off their eight-year engagement, while Macpherson ordered Banjo immediately off the station. As one biographer wrote, “At the cost of a broken love affair, an old folk tune … and some scribbled words on a piece of paper combined to create a song that helped to define the essence of being Australian for generations to come.”

Neither of the women ever married, and Paterson shelved the song for nearly a decade. When he finally released a somewhat altered version for publication, Christina Macpherson’s name did not appear.

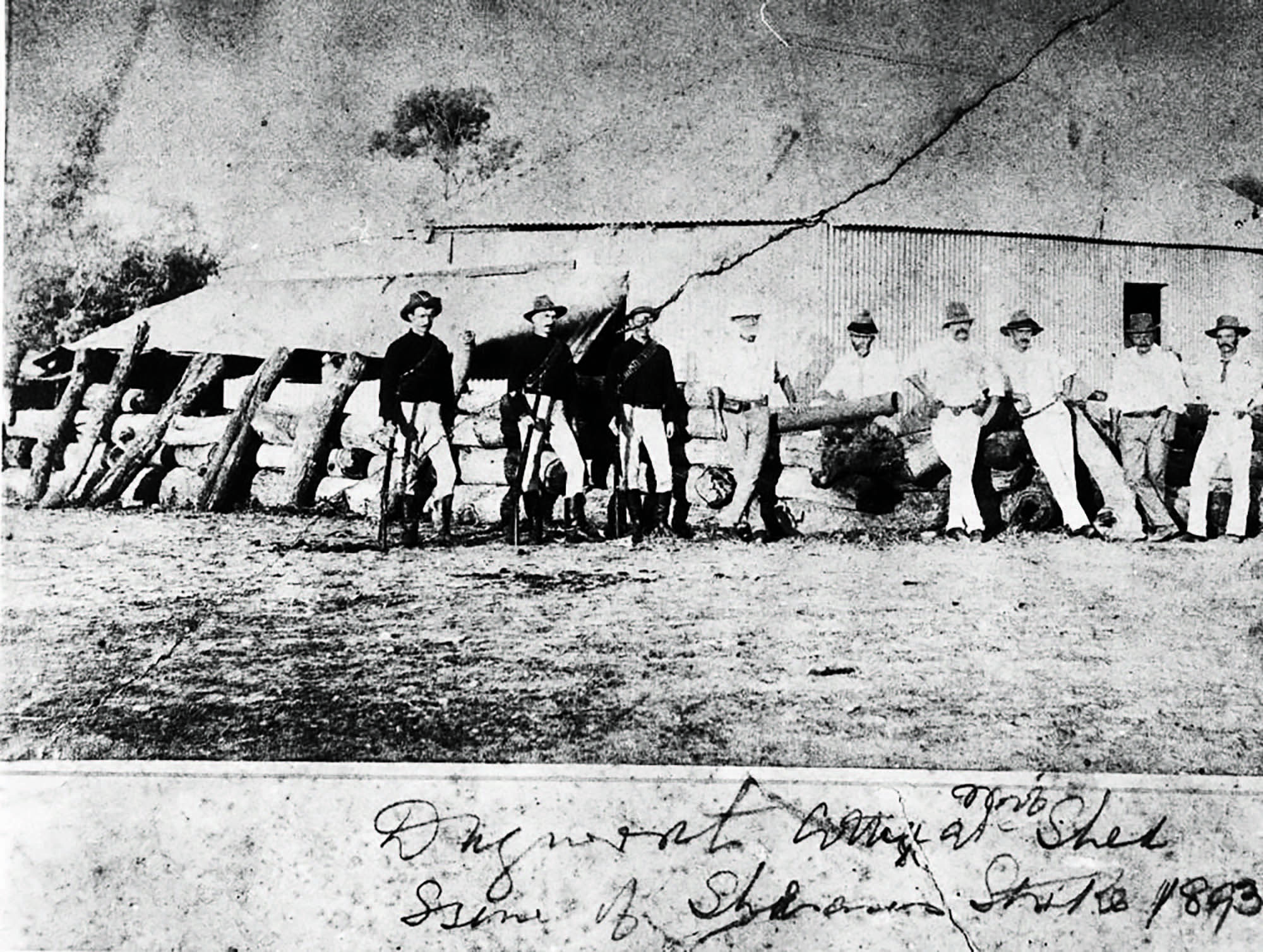

On a darker note, research indicates that Macpherson’s folksy story was based on the actual death of local sheep shearer and staunch unionist Samuel Hoffmeister. In the midst of a violent class war that pitted squatters against their workers, and just a day after strikers burned down Robert Macpherson’s shearing shed with some 140 lambs still within, Hoffmeister’s body was found in a billabong on Macpherson’s property. Although his death was ruled a suicide by “accidental shooting,” some historians have alleged that a group of squatters, including Macpherson, shot Hoffmeister and threw his body into the watering hole.

The original version of the ballad known to virtually all Australians, as well as ballad lovers the world over, ends:

But the swagman he up and he jumped in the water-hole,

Drowning himself by the Coolibah tree;

And his ghost can be heard as it sings in the billabong,

‘Who’ll come a-waltzing Matilda with me?’

[Chorus:] Who’ll come a-waltzing Matilda, my darling,

Who’ll come a-waltzing Matilda with me;

Waltzing Matilda and leading a water bag —

Who’ll come a-waltzing Matilda with me?

The Banjo’s true identity had become known in 1896, making Paterson a much sought-after celebrity. He continued to haunt the bush, frequently leaving his law offices to range in search of subjects for his verse. “Australia still had an economy based on agriculture in the 1890s, but it was gradually migrating to the cities,” says Grantlee Kieza, author of Banjo: The

Remarkable Life of Australia’s Greatest Storyteller, (HarperCollins, Australia, 2020). “Paterson portrayed Australia’s ‘cowboys’ — the stockmen and drovers — as romantic heroic figures. It wasn’t really a matter of nostalgia: These men on the land were integral to Australian prosperity and he saw them as having richer lives than those being forced into the cities.”

Christina Macpherson

Ironically, as a member of the upper middle class, Paterson was perfectly at ease with his urban lifestyle. By now, he lived in a comfortable Sydney suburb, edited a newspaper devoted to thoroughbred racing, rode to hounds, and as an avid supporter of polo, kept a stable of blooded horses. He was, as later described, “every inch the refined city gentleman.”

He nonetheless possessed the ability to paint verbal pictures for his readers that eulogized the carefree, bucolic existence of the country folk — drovers, sheepmen, swagmen — above that of the downtrodden urbanite. In such classics as “Clancy of the Overflow,” Paterson describes his admiration for the drover’s lot, and his disdain for city life:

In my wild erratic fancy visions come to me of Clancy

Gone a-droving ‘down the Cooper’ where the western drovers go;

As the stock are slowly stringing, Clancy rides behind them singing,

For the drover’s life has pleasures that the townsfolk never know.

And the bush hath friends to meet him, and their kindly voices greet him

In the murmur of the breezes and the river on its bars,

And he sees the vision splendid of the sunlit plains extended,

And at night the wondrous glory of the everlasting stars.

I am sitting in my dingy little office, where a stingy

Ray of sunlight struggles feebly down between the houses tall,

And the foetid air and gritty of the dusty, dirty city

Through the open window floating, spreads its foulness over all.

And in place of lowing cattle, I can hear the fiendish rattle

Of the tramways and the ‘buses making hurry down the street,

And the language uninviting of the gutter children fighting,

Comes fitfully and faintly through the ceaseless tramp of feet.

The inspiration for the ballad was somewhat less romantic. The real Clancy was a drover who owed some money, and Paterson’s firm sent him a no-nonsense letter demanding payment. In response, Clancy escaped into the bush, and Paterson received a message from one of the absconder’s semi-illiterate mates stating that Clancy had “gone to Queensland droving, and we don’t know where he are.” Fascinated by the wording, and the idea of such an easygoing existence, Paterson converted the story into one of his most famous ballads.

Not everyone was seduced by The Banjo’s romantic paeans to the charms of the backcountry. Fellow poet and literary rival Henry Lawson skillfully set out to lampoon Paterson’s work. In “The Overflow of Clancy,” he perfectly mimics Paterson’s style, while reversing the poet’s and drover’s roles. In the poem, Paterson is described as a self-satisfied pub-crawling, womanizing socialite.

Lawson’s parodies gained immediate popularity and impelled an ongoing “battle of the bards” between the two poets, who were actually friends. Finally, Paterson got the last word: “But that ends it, Mr. Lawson, and it’s time to say goodbye, / So we must agree to differ in all friendship, you and I.”

A temporary shearing shed at Dagworth Station after arson destroyed the main shed in 1894 (“squatter” Robert Macpherson is fourth from the right). “The shearers staged a strike, and Macpherson’s woolshed at Dagworth was burnt down and a man was picked up dead,” Banjo said in a 1930s interview.

Australia’s bush poetry did not begin with Banjo Paterson and his contemporaries. Rather, it derived from a long culture of folk songs, going back to the early days of “transportation” — convict exile to its shores, mainly from Ireland, and often for life. One of the most prevalent forms was the outlaw ballad. Such Victorian-era “bushrangers” as Ned Kelly and Ben Hall were idealized in traditional verses that were widely sung in venues ranging from taverns to music halls to the parlors of proper homes.

Paterson was well-aware of this tradition. In fact, he made a hobby out of collecting old bush songs and later in life published his collection. He once wrote his own outlaw ballad, describing the demise of local bushranger Johnny Gilbert:

But Gilbert walked from the open door

In a confident style and rash;

He heard at his side the rifles roar,

And he heard the bullets crash.

But he laughed as he raised his pistol-hand,

And he fired at the rifle-flash.

One need not be a scholar of the American West cowboy tradition to discern similarities to the “bad-man ballads” of our own Wild West. At one point in our history, most Americans knew, or knew of, the anonymous composition lamenting the passing of the nation’s favorite outlaw, if only to sing along with any number of covers — by everyone from Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger to Sons of the Pioneers and Johnny Cash — done after the folk tune was first recorded by Bentley Ball in 1919.

The Banjo’s eulogies to the free-roving lifestyle of the bush find parallel in the work of America’s cowboy poets of the same period like Charles Badger Clark Jr., who would become South Dakota’s first official poet laureate — or, as he put it, “poet lariat” — and wrote poems that could easily find a home in Australia’s bush-ballad anthologies.

Paterson refined the art of the Australian bush ballad, drawing on his imagination for stories that were, by turns, amusing, heroic, ironic, and sad. His control of his reader’s emotions was uncanny. His genius — his ability to immediately set the stage and then sustain a breakneck pace — is in full flower from the very first verse of “The Man From Snowy River,” which was published in 1890, as he tells how a valuable colt has run off and joined a “mob of brumbies” (a wild herd):

There was movement at the station, for the word had passed around

That the colt from Old Regret had got away,

And had joined the wild bush horses — he was worth a thousand pound,

So all the cracks had gathered to the fray.

All the tried and noted riders from the stations near and far

Had mustered at the homestead overnight,

For the bushmen love hard riding where the wild bush horses are,

And the stock-horse snuffs the battle with delight.

It goes on for 13 headlong verses, never slackening, and features a climax worthy of the best classical fiction writers. Some say Paterson based the ballad on a story he’d recently heard from a mountain recluse and former horse thief while riding with friends. Paterson always said his characters were composites from stories he’d heard. Whatever his inspiration, for sheer excitement, it can stand alongside anything written by Rudyard Kipling.

Paterson had written news reports as well as ballads for The Bulletin; but a more demanding application of his literary skills lay ahead. When the Second Boer War broke out in late 1899, he immediately had himself accredited as a war correspondent for The Sydney Morning Herald, and — leaving his legal practice — traveled to South Africa with the South Wales Lancers.

Paterson was not the only famous bush poet to do so: His old friend, Harry “Breaker” Morant, joined a ranger company and eventually saw more action than he had bargained for. “The Breaker” was court-martialed and convicted of shooting Boer prisoners. The night before he faced a firing squad, Morant wrote his last ballad, offering the reader some tongue-in-cheek advice:

If you encounter any Boers / You really must not loot ’em, /

And, if you wish to leave these shores, / For pity’s sake, don’t shoot ’em.

Paterson would remember Lt. Morant in a piece published in The Sydney Mail on April 12, 1902, that reveals some remarkable similarities between life in the Aussie bush and life on the Old West range. “An Englishman by birth, [Morant] was an excellent rough rider, and when he was young, with a nerve unshaken, he was a first-class horse breaker and a good man to teach a young horse to jump fences,” Paterson wrote.

“Morant lived in the bush the curious nomadic life of the Ishmaelite, the ne’er-do-well, of whom there are still many to be found about north Queensland, but who are very rare now in the settled districts: droughts and overdrafts have hardened the squatters’ hearts and they are no longer content to board and lodge indefinitely the scapegrace who claims their hospitality; even yet in Queensland it is quite common for a young fellow to ride up to a station with all his worldly goods on a packhorse and let his horses go in the paddock and stay for months, joining in the work of the station, but not getting any pay — except a pound or two by way of loan from the ‘boss’ now and again — and leaving at last to go on a droving trip; but in New South Wales the type is practically extinct.

“Morant was always popular for his dash and courage, and he would travel miles to obtain the kudos of riding a really dangerous horse. … His death was consistent with his life, for though he died as a criminal he died a brave man facing the rifles with his eyes unbandaged. …”

On assignment, Paterson’s writings grew in sophistication. In contrast to the easy lilt of his bush poetry, his reportage was crisp and factual, while maintaining the ability to arouse the reader’s emotions. Ironically, he often wrote — in both prose and verse — in support of the Boers, the sworn enemies of the British Empire:

In the front of our brave old army! Whoop! The farmhouse blazes bright / And their women weep and their children die — how dare they presume to fight!”

Paterson was often in the thick of battle, sending home thrilling, well-balanced reports that were eagerly read across Australia. So professional were his dispatches that Reuters hired him as one of their correspondents. During his tour, he met a young fellow correspondent named Winston Churchill and became close friends with the world-renowned Rudyard Kipling.

Upon his return home in 1900, Paterson embarked on a popular lecture tour across Australia and New Zealand, relating his wartime experiences. Eventually, he tired of the road, and in July 1901, The Sydney Morning Herald sent the 37-year-old Banjo to cover the Boxer Rebellion in China. By the time he arrived, however, the fighting was all but over. After a brief sojourn in London, where he stayed at Kipling’s home and took full advantage of the city’s nightlife before returning home.

By now, Paterson was finished with the legal profession, opting to devote himself completely to his journalism and poetry. Within a year, he took over the editor’s desk at the Evening News — a racy daily paper that combined respectable reportage with National Enquirer-esque headlines (“Priest Murders His Sweetheart!”).

Soon after his promotion, Paterson finally married, wedding Alice Walker, a squatter’s daughter. The two would remain fiercely devoted to one another until his death 38 years later.

Within a few years, Paterson left the Evening News to edit the weekly Australian Town and Country Journal. It was during this time that he wrote the first of his two novels, An Outback Marriage, the story of “a young Englishman on a tour of the colonies, who gets more than he bargained for when he sets out to find the heir to a fortune.”

By 1908, “Barty” and Alice had two children, and — exhausted by the demands of running the Journal and seeking a more “countrified” life for his family — he resigned and went partners on a 40,000-acre “wool-growing property” in the rugged foothills of the Snowy Mountains. All the while, he continued to write his verses of life in the bush. “The Mountain Squatter,” written while on his station, waxes eloquent about the life of the “woolgatherer.”

Here in my mountain home,

On rugged hills and steep,

I sit and watch you come,

O Riverina Sheep!

You come from fertile plains

Where saltbush (sometimes) grows,

And flats that (when it rains)

Will blossom like the rose.

But, when the summer sun

Gleams down like burnished brass,

You have to leave your run

And hustle off for grass.

‘Tis then that — forced to roam —

You come to where I keep,

Here in my mountain home,

A boarding-house for sheep …

Ultimately, the elements won out over the idyllic country life, as fire, flood, dust, and drought rendered the enterprise a complete failure. This, too, he turned into wry verse:

I bought a run a while ago,

On country rough and ridgy,

Where wallaroos and wombats grow —

The Upper Murrumbidgie.

The grass was rather scant, it’s true,

But this a fair exchange is,

The sheep can see a lovely view

By climbing up the ranges.

After a second attempt at farming failed, Paterson was somewhat at loose ends. At the outset of World War I, The Banjo — now 50 — was only too eager to volunteer his services. Unable to secure a posting as a correspondent, he drove an ambulance for the Australian Voluntary Hospital in France.

Ambulance-driving soon proved too dull. An acknowledged expert with horses, he was commissioned a lieutenant in the 2nd Remount Regiment of the Australian Imperial Force, supervising the breaking and training of replacement mounts. Some of these “walers,” specially bred part-thoroughbreds from New South Wales, were ridden in the famous Australian Light Horse charge at Beersheba in late 1917.

Soon promoted to major, Patterson was sent to Cairo as commander of the unit. Two years later, Alice left their two children with her widowed mother and took a volunteer position at a nearby Red Cross station; the couple saw each other occasionally.

Discharged in 1919, the 55-year-old Banjo returned with Alice to Sydney and the life of the freelance journalist. He became editor of the Sydney Sportsman in 1922 and continued to write for various publications.

A decade later, he embraced the new wireless technology, becoming a popular weekly raconteur and broadcast personality on ABC (Australian Broadcast Commission, now Australian Broadcast Corporation) radio. He spoke on sports, farming, Indigenous tribes, the bush — whatever topics captured his interest. And he was masterful; very few speakers could have turned a lecture entitled “Sheep” into an unqualified smash with his listeners.

Well on in years by the early to mid-1930s, Paterson published his second novel, The Shearer’s Colt. The book was met with only middling reviews — the author was accused of anti-Semitism for his portrayal of London’s Jews — and sales were disappointing. He also wrote a popular children’s book of verse, The Animals Noah Forgot, and an anthology of his wartime recollections, Happy Dispatches.

In 1939, the government honored him with a CBE — Commander of the Order of the British Empire — in recognition of his contribution to the field of literature. Later that year, when Australia entered World War II alongside England, “Waltzing Matilda” instantly became the most popular marching and concert-hall song in the nation.

Andrew Barton “Banjo” Paterson’s heart gave out as he sat in a chair waiting for Alice to pick him up from a private hospital in Sydney on February 5, 1941, just 12 days short of his 77th birthday.

Banjo Paterson remains one of Australia’s favorite native sons. His image has graced a number of postage stamps, including Bush Ballads: 150th Anniversary Birth of Banjo Paterson stamp issue, which took first prize in the World’s Best Offset Stamp category in Spain’s Nexofil Awards for Best World Stamps of 2014. His image and verses from “The Man From Snowy River” — microprinted around his portrait and readable only with a magnifying glass — remain on Australia’s current $10 banknote.

His true legacy, of course, is found not in commemorative stamps and legal tender but in his poems and ballads of the Australian bush.

Shine your boots, brush off your iambic pentameter, and check out these cowboy-poetry websites to see when their 2022 gatherings will take place. 38th National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada, (nationalcowboypoetrygathering.org); Lone Star Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Alpine, Texas, (lonestarcowboypoetry.com); 37th Montana Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Lewiston, Montana, (montanacowboypoetrygathering.com); 31st Red Steagall Cowboy Gathering & Western Swing Festival in Fort Worth, Texas, (redsteagallcowboygathering.com).

From our January 2022 issue

Photography: (Cover image) Atomic/Alamy; (Waltzing Maltilda) National Museum of Australia Public Domain; (Christina Macpherson) National Museum of Australia Public Domain; (Shearing shed) John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland Public Domain