When you climb with Kitty Calhoun, you can be sure you’ll end up knowing your butte from your backside.

I drive my rented red Chevy Cruze as deep into Bears Ears as it will go. When the rocks and ruts get too big in the national monument in southeast Utah, I park. Kitty Calhoun — who has guided ice, rock, and alpine climbs across the world for four decades — grabs her pack stuffed with snacks and water and sets off for a trail that will take us to the Citadel Ruins, a rock formation with an ancient Pueblo ruin built into its side.

We hike along the top of Road Canyon. Across the canyon, to our left, horizontal lines in the brick-red rock look like a child’s attempt to put icing on the side of a cake. Green desert plants dot the cake like candy decorations. Beyond the canyon, the two buttes that give Bears Ears its name dominate the landscape.

Calhoun glides atop the uneven terrain like a dancer, as if the rocks and ledges and cacti that will grab my ankles in the three days we’ll spend hiking, scrambling, and rock climbing in Utah, aren’t there. We shimmy down between two boulders, shuffle through a crevice, and emerge onto slick rock. We make a U-turn and walk along a shelf just below where we were moments ago. Now the canyon drops off to our right. We know we’re close to the Citadel, but a knob of rocks obscures our view.

Calhoun turns right around the knob and stops. She makes a noise that sounds like a cheer and a gasp put together. When I turn the corner, she’s almost dancing. We’ve found the Citadel, and it is spectacular. Rising behind her, it climbs into the sky like a rock castle built by an ancient giant.

Many landmarks in Utah have ominous-sounding names: Goblin’s Lair, Hell’s Revenge, Satan’s this-and-that, etc. At least the Citadel’s name makes sense — it looks like a citadel God made out of rocks He had lying around.

A land bridge leads out to it, an epic red carpet daring us to walk across. Now I can’t keep up with Calhoun. She climbs up and over ledges and darts away, as if she can’t wait to see every inch of it.

Over 40 years into her climbing career, Calhoun, who turns 61 this year, still loves to reach new heights, to see new beauty, to lose herself in new adventures. She sees the “awesome” in everyday nature, like the chirping of birds or the changing of the leaves. She gets overwhelmed when nature is showing off, like it does with the Citadel. “This is so cool,” she says, her smile as wide as the canyon behind her. “Not your average trail, huh?”

And she’s not your average guide, either.

Calhoun grew up a self-described Southern belle in South Carolina. When she was a teenager, she wanted to hike the Appalachian Trail, a 2,190-mile ribbon of dirt that runs from Georgia to Maine. Her mom wouldn’t let her, so Calhoun signed up for an Outward Bound class instead.

The class planted in her a love of challenging herself that still drives her. Sports Illustrated called her “indefatigable” and “one of the world’s most-accomplished Alpine climbers,” and that was 27 years ago. Indeed, had sport climbing been an Olympic sport then — as it was for the first time when the Summer Games were held in Tokyo this year — it seems like a safe bet that she’d have a wall full of medals. She has taught climbing to Navy SEALs and nervous newbies and everyone in between.

Calhoun splits time between Utah, where she rock-climbs in the summer, and Colorado, where she ice-climbs in the winter. We run into friends of hers from the climbing world deep in Bears Ears and again at a Thai restaurant in Moab. When I tell this to her son, Grady, he shrugs. “My mom knows everybody,” he says.

Before I flew to Utah, Calhoun and I talked on the phone several times to hash out the details. She emailed me to say she’d bring water, dinner, breakfast, coffee, cream, sugar, pots, pans, a camp chair for me, etc. — basically everything except my notebook, and she probably has one of those in her pack, too.

She considers her climbs — whether they’re in Utah or Nepal, on a new track or one she’s done 100 times — team efforts in which the group works together to share the experience. And that’s true if she’s climbing as a guide or with friends. “She’s a good partner because she’s supportive,” says Dawn Glanc, a veteran guide who has climbed with Calhoun many times, including three trips to Iceland, where they posted numerous first ascents. “She values the fact you’re climbing together so you share the experience together. It’s a partnership. That’s quite nice, actually, and kind of rare.”

Calhoun’s fellow climbers describe her as driven, single-minded, and goal-oriented — all traits her accomplishments verify but her personality does not. She’s way more laid-back than all that and comes across more like a surfer dropped into the mountains than a Type-A personality bent on getting ever higher. Still, that easy manner masks an insatiable drive to get better, even 40 years into her career.

When she sets a goal — scale this pitch, ascend this route, find this ruin — she doesn’t stop until she achieves it, no matter the terrain or obstacles in her way. She emerged as a force in a male-dominated sport, she says, because she was “blessed with a lot of male climbing mentors. I think the climbing world was an early adopter of DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion].”

Calhoun has won grants and sponsorships and has been hired as a guide by prestigious organizations such as Outward Bound and the American Alpine Institute. With three other women, she is co-owner of a business called Chicks Climbing and Skiing, for whom she guided for years before she became part owner in 2015. Under her picture on the group’s website, it simply says “Legend.”

The highly acclaimed all-female guides teach rock, ice, and alpine climbing and backcountry skiing. Chicks turned 20 in 2019, and Calhoun helped produce a video and roundtable discussion to look back at how far it has come and look forward to what’s next for women in adventure sports. She thinks often about what’s next for her, both in climbing and in life.

In climbing, the answer (or one of them, at least) is simple, if also surprising: She wants to get better at falling in rock climbing. There is no real danger in it. She knows the ropes will catch her. Still, every time she slips, her heart skips a beat. “I haven’t gotten used to the cheap thrill. It’s still scary for me,” she says. “If I were to practice it, I would become comfortable with it.”

In life, the answer to what’s next is more complicated.

The day after we hike to the Citadel, we descend deep into Sheiks Canyon to see a series of Native American pictographs, especially one known as Green Mask (because that’s what it looks like). The area has been inhabited dating back 8,500 years and many different cultures are represented in the artifacts and pictographs they left behind.

On the way I’m distracted by the massive, audacious, in-your-face beauty of Grand Gulch — an unending canyon with tan, red, and brown shelves — and also by the tiny, exquisite, subtle details of the desert floor, populated by countless flowers, miniature explosions of yellow, purple, and white.

Watching the scenery instead of where I am going, I slip on slick rock and almost fall into a ravine. “Don’t hike like you drive,” Calhoun jokes. I deserve that. We’ve driven for hours around Utah the last two days, and more than once I nearly ran off the road because I was gaping at Devil’s Desert or Beelzebub’s Backwater or Lucifer’s Landmass and not watching the road.

OK, I admit I made up those names, but, oh, the irony of putting her in danger by something as simple as driving.

Calhoun has so many stories of almost dying on mountains that I’m not sure which one to tell. She has survived avalanches and impassable crevasses and eight days hanging from a mountain on the rough equivalent of a window-washer’s platform.

Once, she almost starved when someone stole the 40 Snickers bars she had buried in the snow. Who steals 40 Snickers buried in the snow? That was one of many questions Calhoun asked herself when she tried to retrieve those cached Snickers, along with other food and fuel, during an ascent of Alaska’s Denali, the tallest mountain in the United States.

Curiously, the thief mercifully left the rest of the food and the fuel, and Calhoun thought she and her hiking partner had enough of both to finish their climb without the precious calories the Snickers would have provided. But as they neared the summit, a storm roared over the top of Denali and pinned them down.

The blizzard lasted one day, then another, then three more. They ran out of food. For five days, they could not move from the spot they had chipped out of the ice, and they had only enough fuel to melt snow to drink two cups of water each per day.

When the storm finally cleared, Calhoun was so exhausted she could barely strap the crampons onto her boots. She and her climbing partner managed to scramble over the top of Denali and then climbed down to their second cache of food on the other side. That drop, thankfully, had been left undisturbed by hungry thieves.

Every time she goes up a mountain, she comes down changed, that time more than ever. “I gained a freedom of understanding of what I can do without,” Calhoun says, “and a greater appreciation of what I have.”

What she has — a life rich in experience — and what she has given away (same) have been much on her mind as the prime of her climbing career has ended and the next phase of it has begun. “Do you ever feel guilty about how your life turned out?” Calhoun asks me as we wait outside of a Thai restaurant after emerging from Bears Ears.

She has survived avalanches and impassable crevasses and eight days hanging from a mountain on the rough equivalent of a window-washer’s platform.

She is really asking about herself. What did she do to deserve the career she has had? And what has she done with it? She sometimes feels as if she might be selfish, a tension that she has wrestled with for years. She spent seven years living out of her car so she could chase every mountain that called to her. She owned two pairs of socks, two pairs of pants, and two sweaters and got by on $14 a week for food. “I would have been a cheap date,” she says.

Through much of her career, she focused only on the next great climb. That made it possible for her to become an incredible climber. But she has tried in recent years to move beyond just being a great climber, to find balance between climbing and life.

She got married, had a son, divorced, remarried (her husband Jay is an accomplished climber and guide, too), became co-owner of Chicks. And yet she has never been far from the mountains.

Now she wants to climb with a purpose beyond herself. “There’s a bigger world out there than just how hard I can climb,” she says. As co-owner of Chicks, she passes on what she knows to other women, who absorb it and pass it on to still more.

And she has become more politically aware. She is particularly interested in climate change — some of her climbs have become last ascents because shifts in weather have made them impassable.

She took me to Bears Ears because it’s beautiful and she wanted to immerse herself in it. But she has another reason, too: the constant threat of development on public lands. “Imagine,” she says as we emerge from trees to a wide-open view of Road Canyon, “if there were oil rigs over there.”

On our last day in Bears Ears, I wake up early in my tent. I make a cup of coffee and wander downhill away from our campsite. I carefully watch where I put my feet to avoid cacti and shift my shoulders and hips to avoid the junipers and pines that dot the landscape.

She has tried in recent years to move beyond just being a great climber, to find balance between climbing and life.

After a few hundred feet, I stop. If there’s a place and a moment that can help me understand how Calhoun could guide climbs for four decades and still get excited about each one, this is it.

The desert sand cushions each step. The wind whispers against my skin, a soft touch cool with the last vestiges of the night still lingering in the air. Animal prints follow an elusive trail … or maybe make their own. Far ahead of me in the distance, the Bears Ears buttes poke into the sky. To my right, the sun peeks over Road Canyon.

As it rises, I hear a strange noise, like a cross between crackling fire and popcorn.

I try to pinpoint its origin. After a few minutes of following the noise, I’m baffled to discover it’s coming from all around me. The junipers and pines are making it. If trees could applaud the sun, this is what it would sound like.

Are the Bears Ears listening, too?

When Calhoun rolls out of her tent, I call her over. “Listen to that,” I say. She leans in toward a juniper. She looks at me in amazement, her expression asking, “What the …?!”

She has never heard that sound before. And with the same expression that crossed her face when she first saw the Citadel, she beams with joy.

From the November/December 2021 issue

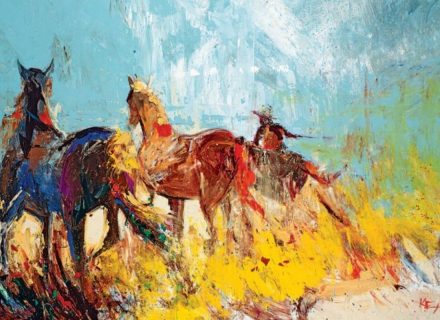

Photography: (All images) Chris Nobles/courtesy Chicks With Picks