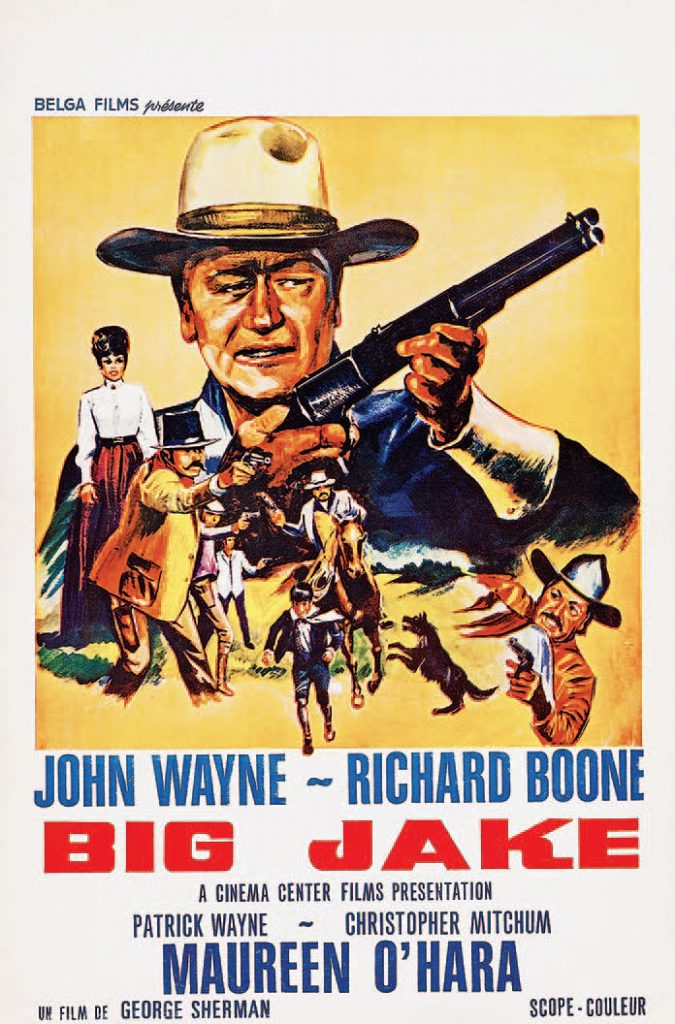

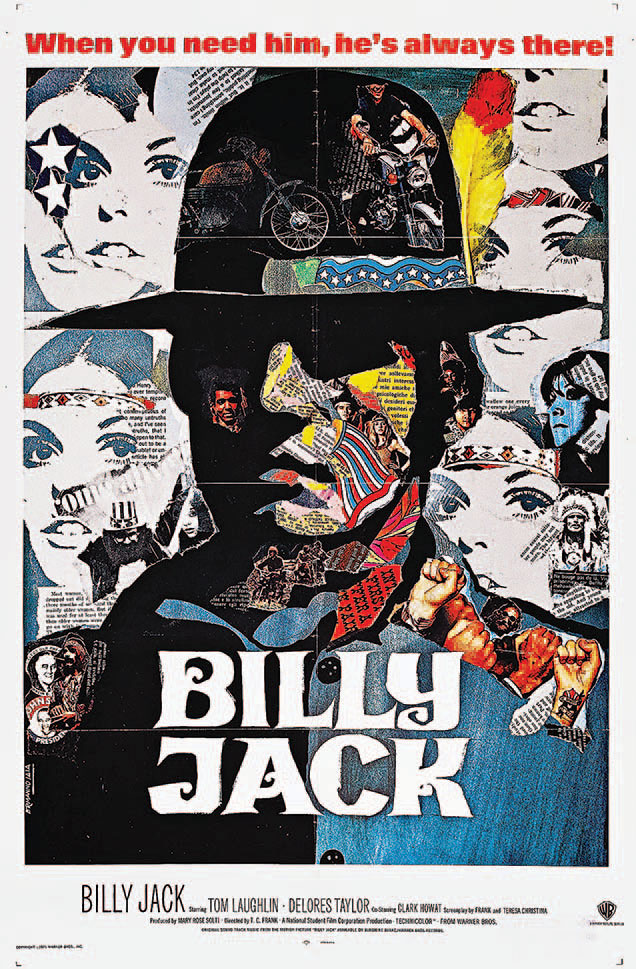

In 1971, traditional (Big Jake) and revisionist (Billy Jack) westerns battled for box-office supremacy.

Fifty years ago, if you were in the mood for a western, there was probably one playing somewhere in your neighborhood; but it might not be the kind you were expecting.

In 1971 the genre was in the midst of a transition, in which new visions of the Old West clashed with more traditional fare featuring stars audiences had revered for decades.

John Wayne, still tall in the saddle 32 years after attaining stardom in Stagecoach, was enjoying a career renaissance after winning the Oscar in 1970 for True Grit. In Big Jake he was joined by his most beloved female costar in Maureen O’Hara, his two sons Patrick and Ethan, and old friends like Harry Carey Jr. Wayne played a rancher on a quest to rescue his kidnapped grandson, played by Ethan. Reviews were mixed (“scarcely distinguished but certainly enjoyable” was the Los Angeles Times assessment), but a rousing climactic shootout sent Duke fans home happy.

Big Jake earned about twice in ticket sales what it cost to make, a success by any standard, but one that paled next to the year’s second highest-grossing film, Billy Jack. The vision of writer-director-star Tom Laughlin, it expanded the legend of a character introduced four years earlier in an otherwise forgettable biker flick called Born Losers. Billy Jack was a Native American, Green Beret, Vietnam War veteran who preached nonviolence before beating his enemies senseless with a Korean martial art called hapkido.

Critics yawned and shrugged, but there was something in this reluctant Indian warrior, and in Laughlin’s laconic but effective performance, that resonated with younger viewers who also felt like outcasts in tumultuous times. Native American author Sherman Alexie recalled his whole tribe piling into a couple of vans and driving six hours to see the film in Spokane, Washington. “Every Indian remembers Billy Jack. I mean, back in the day, Indians worshipped Billy Jack,” Alexie wrote in a 1998 article in the Los Angeles Times. “… We Indians cheered as Billy Jack fought for us, for every single Indian. Of course, we conveniently ignored the fact that Tom Laughlin, the actor who played Billy Jack, was definitely not Indian.”

Made for a minuscule $800,000 budget, Billy Jack would earn $32.5 million, and nearly $100 million internationally.

And so it went in 1971. For every old-school western like Catlow, starring Yul Brynner and based on a Louis L’Amour novel, there was a Zachariah, billed as the first “electric Western” for the inclusion of several rock songs performed by Country Joe and the Fish. Revenge stories in the classic tradition like Shoot Out with Gregory Peck and One More Train to Rob gave longtime western fans the fix they needed; The Hired Hand, directed at a snail’s pace with a cynical sneer from Peter Fonda, likely sent many home shaking their heads.

Burt Lancaster worked both sides of the trail that year: Valdez Is Coming was a fine adaptation of an Elmore Leonard tale, while Lawman, in which he played a marshal as morally ambiguous as the men he pursued, blurred the line between good guys and bad guys. But Lancaster made both films worth seeing.

Perhaps the year’s most controversial release was McCabe & Mrs. Miller, starring Warren Beatty as a gambler with higher aspirations and Julie Christie as his drug-addicted partner in a bordello. Director Robert Altman himself called it an “anti-western” for its deliberate shredding of some tried-and-true conventions of the genre, and the film still stirs up arguments among western fans 50 years after its debut.

“It is not often given to a director to make a perfect film. Some spend their lives trying but always fall short. Robert Altman has made a dozen films that can be called great in one way or another, but one of them is perfect, and that one is McCabe & Mrs. Miller,” rhapsodized Roger Ebert. The venerable 10-volume Motion Picture Guide offered a different assessment: “This jumbled, mumbling, fumbling film is a cult production with those who identify with failure and backstabbing and those with no redeeming virtues whatsoever.” The American Film Institute is in Ebert’s camp: It named the film the eighth greatest western of all time in 2008, and Christie earned an Academy Award Best Actress nomination.

No wonder some moviegoers of the day approached every new release with trepidation. Perhaps some of them figured they had better odds seeing one of the European imports, especially as new arrivals were still opening nearly every month since Sergio Leone and Clint Eastwood kicked off the stateside spaghetti western craze with A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Sure, they were a little quirky and sometimes badly dubbed, but they usually delivered on action and atmosphere. Leone was back in 1971 with the underrated and unfortunately titled Duck, You Sucker!, but 50 years ago Lee Van Cleef may have been the busiest actor in Spain with three new releases: Bad Man’s River, Captain Apache, and Return of Sabata.

Despite the changes in tone and provocative nature of the westerns of a half-century ago, it’s hard not to look back with envy on a time when the volume of new releases rivaled any other movie genre. This was also the year of Hannie Caulder with Raquel Welch, one of the films Quentin Tarantino cited as an inspiration for Kill Bill; the delightful comedy Support Your Local Gunfighter, with James Garner back in the cowboy con man role he honed to perfection in Maverick; and The Last Rebel, a Civil War-era western starring New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath.

If all else failed, you could always stay home and watch Gunsmoke.

From the November/December 2021 issue

Photography: (Big Jake) courtesy Everett Collection, Inc./Alamy Stock Photo; (Billy Jack) courtesy AF archive/Alamy Stock Photo