For the next year, the rare Major Lunar Standstill will grace Colorado’s Chimney Rock and light the kivas at an ancient Chacoan community.

Beneath a bluff braced against blazing blue sky, the ancient ruins of a Chacoan community unfold below two rock pillars in southern Colorado. Like the better-known ruins at nearby Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde, these sturdy pit houses and kivas made of pale stones are stunning in their tight masonry and sheer range — an estimated 6 million stones moved by hand, serving a population that was likely larger than what exists in the area today.

Pretty magical, to be sure. But there’s something even more mysterious and special going on here. It’s a relatively recent discovery, and one that took many trained eyes to see, perhaps because it’s a rare celestial event seen only every 18 years.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Chimney Rock National Monument

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Chimney Rock National Monument

When I first started reading about a Major Lunar Standstill, I was a bit skeptical — how had I not heard of such a thing, sky lover that I am? Certainly, we all know the sun has a standstill: Solstice, with sol meaning “sun” and stit meaning “stopped,” is the day when the sun “pauses” in the sky at its highest northern point and begins to move south again. Most of us are aware, too, that cultures around the world have marked the solstice and equinoxes — from Stonehenge to Machu Picchu to Chaco Canyon, important structures align with the sun’s movement across the sky.

The moon, too, has a solstice — called a lunistice, which I find an endearingly beautiful word. And while most of us are familiar with the rotation from full to gibbous to new moon, my guess is most don’t know about a slower cycle as it moves from north to south, which is caused by a slight wobble in its orbit around the Earth. This cycle takes 18.6 years to complete, and when it reaches its apogee, it appears to rise in the same area for about three years, known as the Major Lunar Standstill. This is such a long and subtle cycle of moving across the horizon, it’s no wonder that most of us don’t notice, nor are aware that we’re currently experiencing a lunar standstill, which will occur only a few times during the course of our lives.

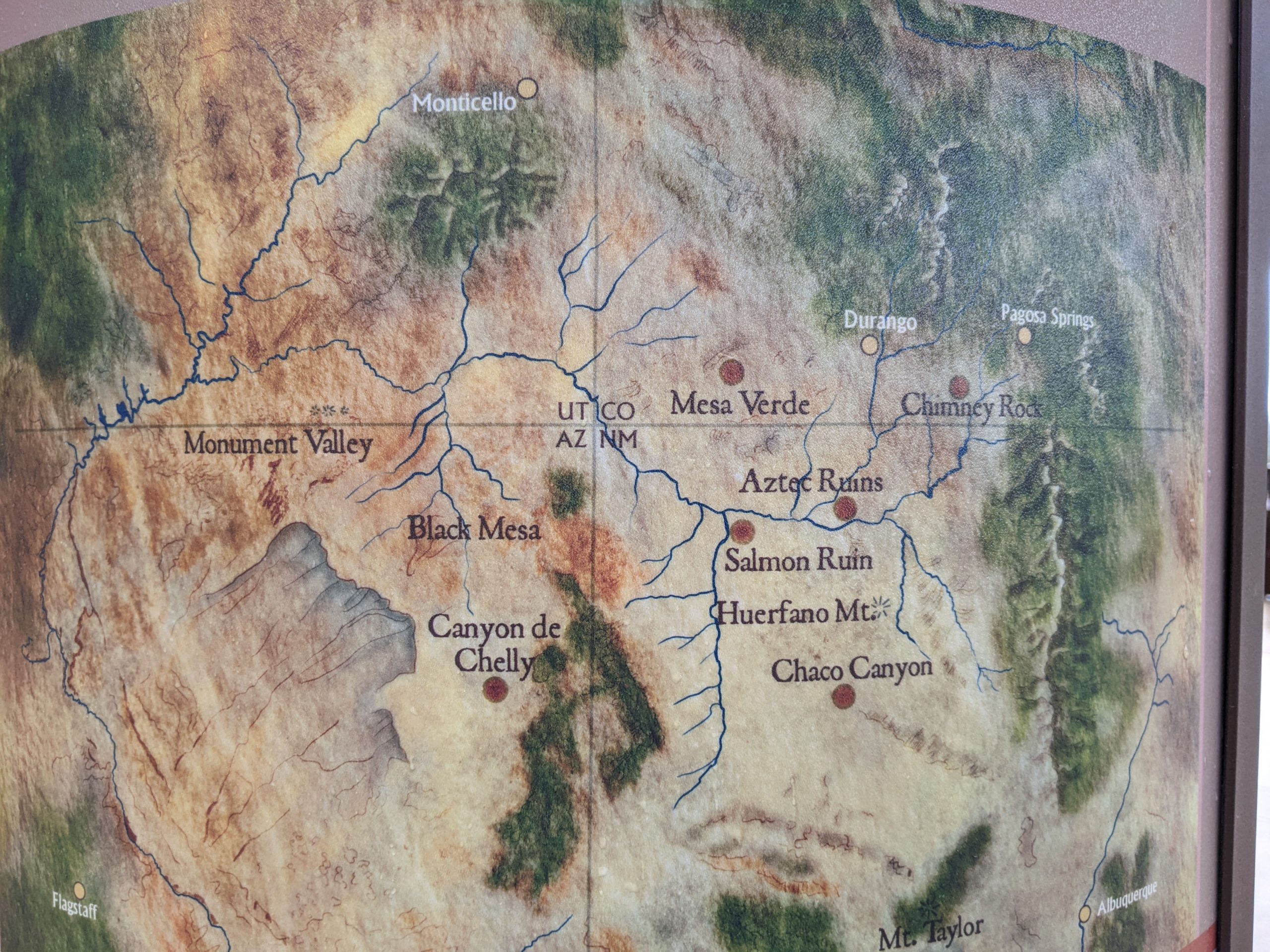

But here’s what really blows my mind: There is only one known place on the planet where a geological feature happens to frame this lunar standstill, and that is the two pinnacles at Chimney Rock National Monument located west of Pagosa Springs, Colorado. These two rocks, known as Chimney and Companion Rock, are 7,400-foot-elevation pillars that rise 315 feet into the sky. Certainly, they are beautiful in and of themselves, but what’s more stunning is that the ancestral Puebloans perfectly positioned their kivas in such a way so as to capture the moonrise between these rocks every 18 years.

As soon as I heard about this wonderful mix of sky wisdom and archaeology and celestial wonder, I knew I had to see it. A road trip across Colorado dotted with visits to hot springs got me there, and soon I was on a tour led by passionate volunteers who were as excited about this rare event as I. As we hiked alongside the ruins, I knew my impulse had been a good one. A raptor floated alongside our tour group, as if guiding our way. Cliffroses bloomed white-pink flowers, and a few blue-collared lizards calmly watched us walk by. Awe is the word for what I was feeling — not only because of the expansive landscape, but because of the incredible sky wisdom obvious here.

“These ancient peoples knew that the moon moves across the horizon for 18 years, then stops, and then rises for 3.6 years in the exact same place,” says Michael Bezney, a lawyer who has made education about this place his passion and who guides tours regularly. “There’s only one other place known to us where this occurs, and that’s Stonehenge, where placement of some of the tablets captures this same event, which means the Druids and the priests of Chacoan culture had something in common ... ” Here, he trailed off and paused to look across the vast treed landscape of the San Juan Mountains, then up at the pinnacles, then down at the ruins. “It’s amazing, just amazing.”

Lynnis Steinert, who is the longest-serving volunteer here, having donated her time and care for 25 years, has a particular love of this valley. Her family homesteaded nearby in the 1900s. “The land speaks to me,” she tells me. “The smell of the sagebrush and pinyon, the wind rustling, the ancient-feeling nature of the land itself. I feel a connection to the land and to those ancient people. I admire how they didn’t just survive, they prospered.”

She was equally entranced by their astronomical knowledge. “This moonrise we’re talking about, it only lasts four to six minutes. Imagine building a structure to capture something that you can only see for three years, every 18 years, and only for a few minutes. That’s one of the amazing and enduring mysteries of the place.”

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Herb Grover (herbsfieldnotes.com)

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Herb Grover (herbsfieldnotes.com)

The path of understanding the purposefulness of construction of the Great House is a bit of a miracle story in itself. Scientists who study ancient astronomical knowledge — archaeoastronomers — first assumed that the structures here were related to the sun, as so many structures are, including those at nearby Chaco Canyon in New Mexico. But when they tried to figure out how the ruins might line up with the sun’s path, they were stymied — they waited and watched, but there was no clear reason for the kiva’s location. What, exactly, were the Chacoans observing?

In the 1970s, a group of archaeologists used dendrochronology — tree-ring dating — on some of the timbers found here. They discovered that construction of the kiva took place in 1076 and 1094. This was a major “aha!” moment: It seems no accident that they were built exactly 18 years apart, and each during a Northern Major Lunar Standstill. The moon was the organizational force here, not the sun. Not only were the kivas built during this time, they were positioned such that the moonrise was best seen from the Great House.

The epiphanies don’t end there, though. Another big aha! was the realization that this community was connected to Chaco Canyon, 90 miles to the south, which is widely regarded as the major spiritual center and trading center during this time. In the 1980s, a local high school student wondered if residents at Chimney Rock could be in communication with Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. She organized her high school companions to look for fire pits on the bluffs, which they indeed found. Rather than building fires to test her theory — not a good idea for obvious reasons — they used mirrors. Ta-da! From bluff to bluff, they were able to see one another in lines extending all the way to these other major communities.

As I stood on the bluff listening to Bezney explain these wonders, I gazed in the directions of Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon, imagining fire pits lighting the way. He reminded us that communicating important solar events was not only ceremonial or simply fun, as it might be for us today. Knowing and communicating time markers was absolutely a matter of survival. Predicting when to plant, when to harvest, when to conserve for winter — these were essential skills. Beans, squash, and corn need to be planted as soon as possible to take advantage of the short growing season before the freezes of fall come. Often referred to as “the three sisters” by Native cultures, these three crops nurture each other when planted together, the beans naturally absorbing nitrogen for the squash and corn, for example.

“With today’s varieties you need 80 frost-free days to grow these crops,” Bezney explained, pointing to the valley below, where water is more abundant and where the crops were grown. In the days of the ancient Chacoans, it was 100 to 120 days. “And this is as far north as you can get and do that.”

What’s more, he noted, it’s been suggested that Chaco Canyon served as the first bank of sorts, where these peoples could take crops in years of abundance to trade with those who had bad years, thereby getting credit to use when they themselves had a bad year. Since rains can be so spotty in this area, it’s entirely likely that one valley’s crops might fail, while another thrives. This trading and banking system was a way to support a very large community in arid and hostile conditions.

“At Chaco Canyon, they’ve found parrot feathers from Central and South America, shells from both coasts, copper bells from Central America, bison pelts from North America,” Bezney said. “That was a major trading hub. They had six-story buildings at Chaco Canyon! What a metropolis!”

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Rob Hagberg, CRIA Volunteer

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Rob Hagberg, CRIA Volunteer

Collaboration and thriving community are not only a thing of the past, though. They were wildly evident on the very tour I was on, which was led by volunteers from the Chimney Rock Interpretive Association and the U.S. Forest Service. This collaboration is one of the strongest partnerships in America, with volunteers and a governmental agency working together in tandem. This friendship was established early on, when volunteers at CRIA worked to protect this area, cheering when it was declared a National Monument under the Obama Administration in 2012. While the USFS now manages the area, it’s the volunteers from CRIA who continue to give a wide variety of tours, everything from plant identification to history to stargazing.

Our group, too, was uniquely diverse: visitors from Belgium, Germany, and Bezney’s niece, recently rescued from Ukraine. As we stood together, taking in the history, I felt a camaraderie not only in our group, but in knowing that there are 24 Chimney Rock Affiliated Tribes who have ties to this area and continue to celebrate its significance, particularly at a gathering each August.

While we don’t know what the ancient people here called themselves, they are known today as Ancestral Puebloans, and Chacoan refers to a distinctive period within that group, marked by their arts and technologies. Indeed, one can clearly see the difference between the older Ancient Puebloan masonry, with its looser-fitting rocks, versus the Chacoan structures, where rocks are very tightly fit.

“Don’t forget,” Steinert reminded us as we stood in front of a dusty wall. “They had no beasts of burden. Can you imagine? All these rocks carried by hand. And given that the Chimney Rock community was at its peak between approximately A.D. 850 and A.D. 1200, that means this wall is still standing strong after nearly a thousand years.”

Indeed, the whole place is stunning: the landscape itself, the patterns of the moon, the culture that tracked it. Steinert has been lucky enough to see the standstill a couple of times. “I had the great pleasure to watch two lunar standstills at Chimney Rock 18 years ago,” she said. “It is an awesome experience. The glow from the moon illuminates the back side of Chimney Rock, and then the bright moon starts coming up between Chimney Rock and Companion Rock. The standstill lasts for five to eight minutes before the moon goes behind Chimney Rock and then reappears to the right of the Rock.” Steinert grew a little breathless at the memory. “Imagine a group of 30 people gathered together on a night lit only by the moon. During the moonrise, there were no sounds from anyone. The moonrise between the chimneys took everyone’s breath away. I think the standstill is special because it links us to our humanity through eons of time. We humans have been watching the moon and observing its complicated patterns forever. As you watch the standstill, you can feel your ancestors and that connects you to your humanity.”

Though it was still daylight during my visit in anticipation of a mystical moonrise, that sense of connection struck me. As we stood below the two great pinnacles, distant thunderclouds boiled up in the sky. I hung back from the group so as to take a moment to acknowledge the respect and reverence I was feeling. I looked down to see a bright green lizard stilled on a stone next to a bright orange paintbrush flower, the colors each so intense and opposite. Magic at my feet, magic in the skies.

Humans did not invent time — but we certainly have a long history of marking it. The rhythms of the sky continue to guide us, unite us, delight us. Looking up can bring us together, even across time.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Chimney Rock National Monument

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Chimney Rock National Monument

When To See It

During the Northern Major Lunar Standstill, the moon will rise in approximately the same space for about three years. The best time to see the moonrise between the pillars is August through November, when the moonrise between Chimney Rock and Companion Rock ranges from crescent to nearly full. The very best remaining time will be the full moon closest to the winter solstice in 2024 (December 21). Be warned, though, that night access is limited in the park due to safety concerns. Contact the Forest Service or CRIA about viewings and scheduled events.

Chimney Rock Interpretive Association: chimneyrockco.org

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Chimney Rock National Monument

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy Chimney Rock National Monument

From our May/June 2024 issue.