At home in up-to-date cow town Kansas City and out West on horseback in the Canyonlands, Marlin Rotach captures cowboys a la Caravaggio.

Kansas City is a revelation of a town, full of hidden gems — artist Marlin Rotach among them. It’s a city that blends beauty and Western bona fides for a distinctive character — so, too, Rotach’s wonderful watercolors.

His home, KCMO, is a legitimate cow town with a long cattle legacy beginning in the late 1870s, when it was home to the second largest stockyard complex in the country. Today it remains world-famous for its steaks and barbecue and the American Royal, which kicks off in August and runs through December with the World Series of Barbecue, rodeo, equine events, and livestock shows.

In this beating heartland of the country, you will find all sorts of visual and cultural inspiration: elegant boulevards and lots of fountains (more than any city in the world, bar Rome), the American Jazz Museum and Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in the 18th & Vine Historic Jazz District, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, historic Old Westport, and the Country Club Plaza. You’ll also find some of the nicest people in the world, and Rotach is definitely one of them. He makes his home and his art in the heart of it all, in a charming stone house in the historic and “quintessentially KC” neighborhood of Brookside. For all his awards and renown, he’s as unassuming and approachable as the town itself. But as humble as he might be, he begins every painting with the high expectations of the master watercolorist he is.

“The goal is always to exceed expectations,” Rotach says. “The work must be ambitious, otherwise what’s the point? There has to be something in every painting I do that I say, ‘Can I pull this off? Do I know enough to make this happen?’ There must be some aspect of it that I challenge myself with something new to try.”

We talked with Rotach about his Western watercolors, his painting that became this year’s 125th anniversary Cheyenne Frontier Days poster, and how John Wayne reciting “America, Why I Love Her” at the Flint Hills Rodeo made for an unforgettable artistic moment.

Cowboys & Indians: What early influences paved the path for your life as a Western artist?

Marlin Rotach: I grew up in Salina, Kansas, on the edge of town in the 1950s. Salina was predominantly a military town, but it was pretty country. My dad was a commercial artist working for the telephone company at the time. His job took him around to the surrounding small towns, where he became friends with all the farmers, and they hung out together at the local diners — we got cream directly from their cows. Everything was Western in those days, and all of that was transferred to me. We’d go to my grandma’s house, which was an hour drive, and he would sing cowboy songs all the way in the car; he knew all the words.

My father went to Montana, where he learned horse training from C.O. Williamson, a man who had grown up with the Nez Perce Indians. He taught my dad the Nez Perce approach to horse training. So, between my dad’s jobs and all his various accomplishments — horse trainer, high school football star, military man, square dance caller, horseshoe-pitcher champion, and magazine cartoon artist — I grew up with cowboys, horses, billboard layouts, type books, paint and brushes, and, most importantly, encouragement from a variety of influences. By the end of grade school, I had my first horse and was spending time with ranchers and horse people. The interesting thing was, my dad was John Wayne; I was a hippie. He would have loved for me to be a sports hero, but I had chronic asthma as a kid and was too weak to participate in those activities. So I got into art instead.

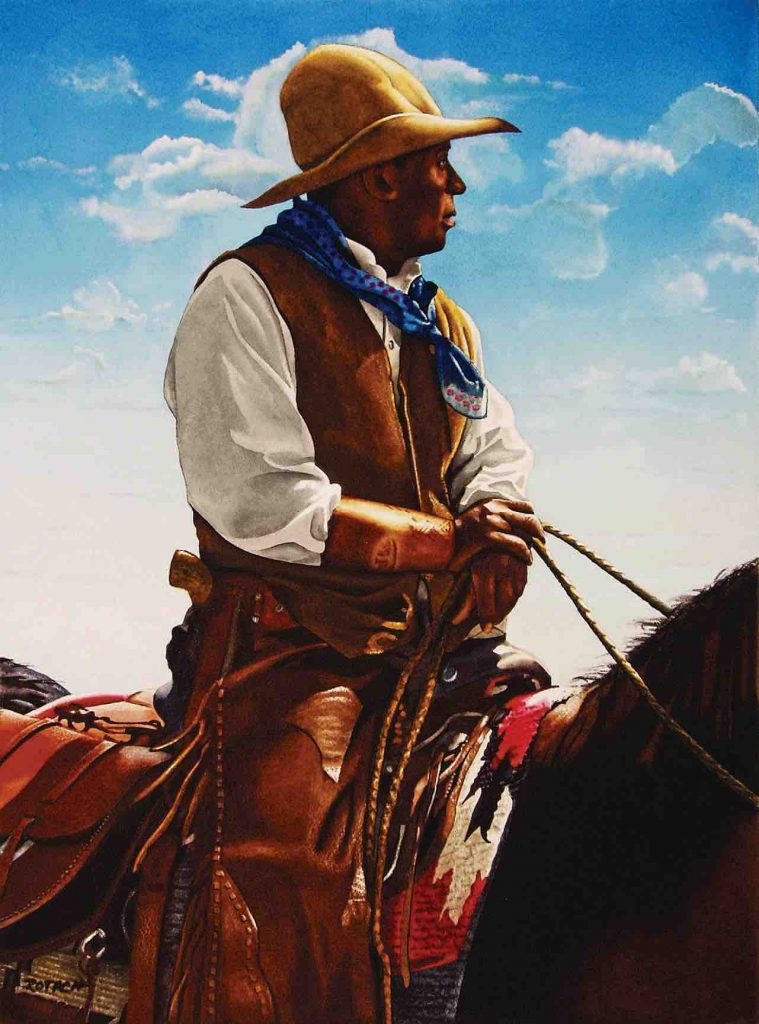

Cowboy

C&I: When did you first discover your love of painting and how did you come to realize it would be your lifelong profession?

Rotach: From my earliest memories, art has always played a role in my life. My mom was a nurse and didn’t want me to pursue art at all and even forbade me to take art classes in school. She wanted me to be a doctor, to have a reliable living. And while it was a time when men generally would not steer their sons to do art, my father quietly encouraged me. For all the things my dad and I didn’t have in common, we did have this. I was drawing horses by the time I was 3. The compositions were horrible, but he helped me understand shapes and how to put animal forms together. In kindergarten I drew the Three Little Pigs and Big Bad Wolf. It blew everyone’s mind and was put on display in the hallway. After that, my entire grade school years became, “We need a mural — hey, go get that guy in the third grade!” That’s pretty much how it started, and it grew from there. In the late ’60s to early ’70s, I went to [Kansas State University] to pursue my art degree. Everything in that period was abstract expression, but it taught me the importance of composition and how to break up a page in an interesting way.

C&I: What accounted for your transition from abstract expression to being a watercolor master of realism?

Rotach: It was a flow. I went from painting abstract to painting portraits to silk-screen landscapes to tropical paintings. I’ve worked in oils, acrylic, silk screens, woodcuts, even art-glass lamps. But it was during my tropical period that I really discovered my love for watercolor.

I was an avid scuba diver for 15 years. During that time, I was doing exotic trips, taking photographs, and painting tropical scenes. A local frame distributor wanted to use one of my photographs for a regional framing competition. I suggested doing a watercolor instead; he was agreeable to the idea and that became my first serious watercolor that started the whole thing. From there, scenes from Tahiti led to florals. When I started doing realistic watercolor it was like my hand went into a glove — I found my thing! But the medium dictates a lot of what happens, and what I quickly discovered was how unforgiving watercolor is. I threw away probably three-fourths of the paintings I did at first. You never really master watercolor. Just when you think you’ve got it, it throws something new at you and says, “Oh, yeah? Try this!” [Laughs.] But that’s the beauty of it: You’re always discovering something new and different. Once, when I was in Hawaii, I pulled into a hotel parking lot and when I got out of the car I was dumbstruck by the vibrancy of the flowers. I just stood there staring at them. I shot some photos, ran back, and painted the flowers, and that became the first watercolor I ever got into the National Watercolor Society — flowers from a parking lot in Hawaii!

C&I: The depth, richness, and realistic expression of your paintings are extraordinary. How are you able to accomplish that in watercolor — a notoriously difficult medium not typically known for its intensity, deep contrast, or powerful light-dark sharpness?

Rotach: The most major art influence in my life has been the Italian baroque artist Caravaggio. He is [one of the artists] credited with developing chiaroscuro, a technique characterized by high contrast and figures coming out of darkness. I saw my first Caravaggio painting, John the Baptist, very early on in my abstract period and knew that was what I wanted to do. There’s a subgroup of chiaroscuro known as tenebrism — super-extreme with pitch-black background. The difference between oil painting and watercolor is that watercolor is based on the reflection of light — light bounces off it — whereas oil absorbs light. I wanted the very sharp lines, deep colors, powerful contrasts of light, dark, and shadow of tenebrism and was frustrated because I was having trouble getting that.

What I learned about painting in watercolor is that you have to be somewhat of a chemist. There are staining, sedimentary, and semiopaque paints, and if you don’t know what makes up the paints, how to apply them, and how the light will react, you end up with mud. Also, one of the hardest things [in this medium] is getting an even tone, especially a deep, rich black without getting brushstrokes or variation of any kind. It took me a long time to come up with a paint combination to get the velvety black I wanted, but I kept experimenting until I learned the chemistry of the paints and finally arrived at the perfect amalgamation.

But the thing that really made me understand how to achieve the richness of baroque paintings was something you’d never imagine. The traditional way to paint watercolor is to start light and work to dark. That wasn’t working for me — I couldn’t get the crispness I wanted. I came across some 1900s black-and-white postcards and was mesmerized by what I saw. They had a technique of printing a black-and-white photograph first and then hand-coloring the card — the opposite of traditional watercolor technique — to make a very sharp image. I wondered if it just might work. I decided to follow the old postcards, defy tradition, and paint dark to light. When I was done, I couldn’t believe it. It worked perfectly.

C&I: For years, you channeled Caravaggio in your florals, in watercolor rather than oils. And you paint Western themes using the same baroque intensity, color, and boldness. Why did you ultimately choose Western themes?

Rotach: I’ve always loved horses and believe they are the most beautiful creatures on the planet. Now that I’m older, I am reflecting a lot more on all the connections my dad made to the Western life. I started shooting rodeos in the Flint Hills near Emporia, Kansas, and that led to doing all things Western. The first time I went to Cheyenne [Frontier Days] was in my tropical years, so there I was in my Hawaiian shirt and cargo shorts. They have tryouts for the rodeo going on in the days prior to the events, and they let you go almost anywhere you want if you’re an artist. So I went over to take pictures. Here I am in the loudest Hawaiian clothes you can imagine and next thing I know, there’s a guy on each side of me grabbing my elbows and telling me, “You gotta come with us.” I’m thinking, What the hell did I do? So they take me out in front of the stadium and there’s this huge billboard that says “If you go past here, you have to be in Western dress: long-sleeve shirt, jeans, a cowboy hat, and cowboy boots.” I immediately walked over to the Wrangler Western store, bought a cowboy outfit, and headed right back.

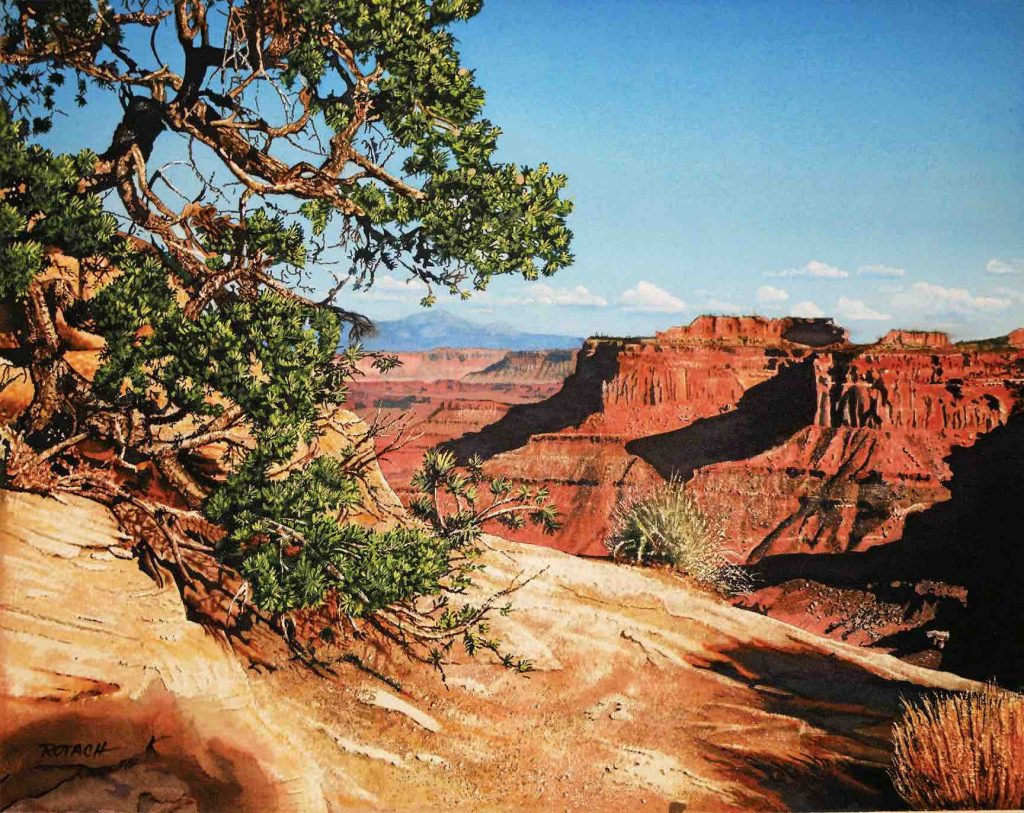

The American Royal — an annual horse show, rodeo, livestock show, and barbecue competition in the Kansas City metropolitan area — decided to try an art show and wanted to feature my Western work. From there, I applied for Cheyenne Frontier Days and started doing Western shows. I met Don Weller and Cindy Long, two highly revered Western artists. We became good friends and Cindy prodded me on. She talked me into going to Utah. On a drive from Colorado to Utah I started seeing all the red cliffs and said, “This is all the movies I saw as a kid!” I don’t think I ever really thought that stuff actually existed — I was dumbstruck. By the time we got to Canyonlands National Park, I was going, “Oh, my God!” I hadn’t done landscapes in years and had always told people that the last thing the world needed was another landscape painter. But I saw challenge in Utah and started doing straight landscape paintings.

Court of the Pale Queen

C&I: You live in a historic cow town and you paint cowboys, but are you a cowboy?

Rotach: I am not a cowboy, I am not a horseman, but nobody loves the West more than I do and nobody thinks horses are more beautiful than I do. The first time I went to Utah, to my friend Colin Fryer’s ranch, his top hand, Devon Dixon, asked me how experienced I was with horses. I told him, “Well, I used to ride, but I haven’t been on a horse in 40 years.” He said, “OK, I’ll give you Bon Jovi.” Everyone else on the rides has these spirited horses; Bon Jovi is a paint pony and he’s like me — he’s a mellow dude. I love Bon Jovi. He knows who I am. If I tell Bon Jovi to go, Bon Jovi goes. If I tell him to stop, he stops, and I get to take all the pictures I want, and then I say, “OK, let’s go.” We’re in total agreement. On my first trip there, they said, “We’re going to climb a mountain on horseback” and I had no idea how long it would be. We started at 10 in the morning and got done at 7 at night. I could hardly walk when I got off the saddle. Nobody had been over the mountain in months and tons of timber had fallen over the trails. Everyone else was leaping over it with their spirited horses, but not Bon Jovi. He walks up to the timber, throws his front leg over, moves up a little bit, throws his back leg over, and I’m thinking, Oh, this is just too freaking cool. I could take pictures the whole time we were crossing over timbers. He was so mellow. I’ve got to give credit to him, because if it wasn’t for him, it wouldn’t have happened. None of the other artists are able to get the

shots that I can get because they’re having to deal with their horses. I barely have to hold the reins. [Laughs.] Devon gives me crap because I call in advance before my trips to Utah and he says, “You’re the only grown man that requests a pony.”

C&I: Is there a painting you’ve done that captures the essence of your impressions of Utah and your creative process?

Rotach: In the painting When It Rains, I was out riding with Devon. He was trying out a new horse for his ranch and was giving it commands to see how it would react. I started shooting and when I looked at one of the photographs, I saw something totally different from what was actually happening. The horse was just responding to his commands, but I envisioned a narrative: Imagine you’re going out in the West, in this area in Utah, and you’re on your horse and get caught in a storm and there’s a rattlesnake on the ground. So, what was actually a sunny day and a horse just following commands became a desert storm with lightning, dark clouds, and a horse reacting to a rattlesnake that wasn’t actually there. The narrative directs the painting, and the painting tells the story.

There’s always something new around the corner that is fascinating. The last 30 x 40 I did — I love doing large paintings — was from a photograph of wrangler Jake Smith. I was riding with him in the middle of the afternoon. Jake was looking up at something in the sky, and I thought, If I turn this into a night scene and have him looking at a falling star, that’d be pretty cool. So, the entire spectrum of color changed because to do night scenes, everything in the painting has to have blue in it. Much of it is layers and layers of underpainting: cool shadows, warm shadows, deep darks, medium darks. In some of my landscapes I have 10 layers of underpainting, and anything you see in white is untouched paper. All the things around the white make it jump.

Call of the Canyon

C&I: Have you painted the same painting more than once, as new ideas inspire you?

Rotach: I painted Color Guard for the American Royal, and they loved it so much, they turned it into a poster. I did it originally as a small painting, not much bigger than the poster. When I took the photograph of the cowboy with the flags behind him, I knew it was going to be incredible. It was at the Flint Hills Rodeo, one of the first rodeos I started going to. This wrangler rode up and the color guard were right behind him. Suddenly, over the intercom, comes John Wayne reciting “America, Why I Love Her,” followed by the national anthem. I’m telling you, I’m goose-bumping now, but at the time, I thought, Oh, my God, this is a moment not to be forgotten. I told the person who bought it that that painting was a preliminary study, but that someday I would do a bigger version of it and change some things.

Well, it was at least a decade that I held onto that image, and I just followed through on it last year. I wanted it to be something really special, so I resisted repainting it over the years, waiting for a really special event. It was the 30th anniversary for the art show in Cheyenne, and I knew it was the right time. I used the same cowboy but changed the two original limp flags to one flying flag. It was sold to the permanent collection of Cheyenne, and that image is going to be the poster for the 125th anniversary this summer.

C&I: Has your art given you the gift of being able to see the small details in all the life and things around you?

Rotach: Without a doubt. I could walk around the block and find a hundred paintings. You’ve got to remain a student all your life, stay open to new ideas, and see things in a new way. It keeps your life vital. I look at flowers or a harness on a mule or a saddle on a horse and say, “Wow, I’ve never noticed that before.” I remember one time on a trail ride in Utah I was mesmerized by what was before me. I was looking at these red cliffs and analyzing what colors I would use in my paints to achieve this and replicate it two-dimensionally. I can get lost for hours just looking at detail. I can ride with someone in a car and get enthralled by a tree line — seeing how the light is bouncing on the bark and how various leaves are going in and out of shadow. Painting has so enlivened my life. It’s my passion.

Light gives life. I don’t do depressing paintings. You have to have darkness to see the light, and so many of the difficult things that have happened in life — all the challenges and trials — have given me such appreciation for an average day where nothing bad happens, you know? What a gift that day was! Whether I’m seeing the head of a horse or a flower or a human, I’m seeing potential there. It’s just a matter of being able to get what I see in my brain transferred through my hands through that brush onto the paper.

Before this quarantine, I was pretty autonomous, but I didn’t realize how much I needed people before it happened. Being able to share thoughts, experiences, and art with people is my soul reaching out and touching their soul. I also owe so much to my wife, Carol, who took care of all the daily things to allow me to do my art. I wouldn’t be where I am today without her.

C&I: Before we go, do you have a favorite painting?

Rotach: My favorite painting is my next one!

Marlin Rotach is represented by Sorrel Sky Gallery in Durango, Colorado, and Santa Fe (sorrelsky.com). See his work August 7 – September 26 at Hold Your Horses! at Phippen Museum in Prescott, Arizona; November 12 in Small Works, Great Wonders at National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. With Western watercolorist Don Weller, Rotach is curating the exhibition The River Flows, October 2, 2021 – February 6, 2022, at the Phippen. Rotach and Weller are the subjects of the two-man show Shared Visions: The Art of Don Weller & Marlin Rotach at Northeastern Nevada Museum, December 14, 2021 – April 24, 2022 in Elko, Nevada. Visit the artist online at marlinrotach.com.

From our August/September 2021 issue

Cover Image: American Anthem

Photography: (All images) courtesy Marlin Rotach