The Queen of Tejano Music was murdered 25 years ago in Texas at age 23, but her legacy will live forever in the hearts of old and new fans alike.

You’ve seen the face and the likeness — on street murals from San Francisco to Chicago, on a bridge in San Antonio, on commemorative drinking cups and T-shirts, on bumper stickers and album covers. The image is unforgettable: a beautiful young woman with full red lips, burnished brown skin, and a full head of dark hair.

Maybe you’ve heard her music, or just heard her name. Either way, you can’t help but wonder: Who is Selena?

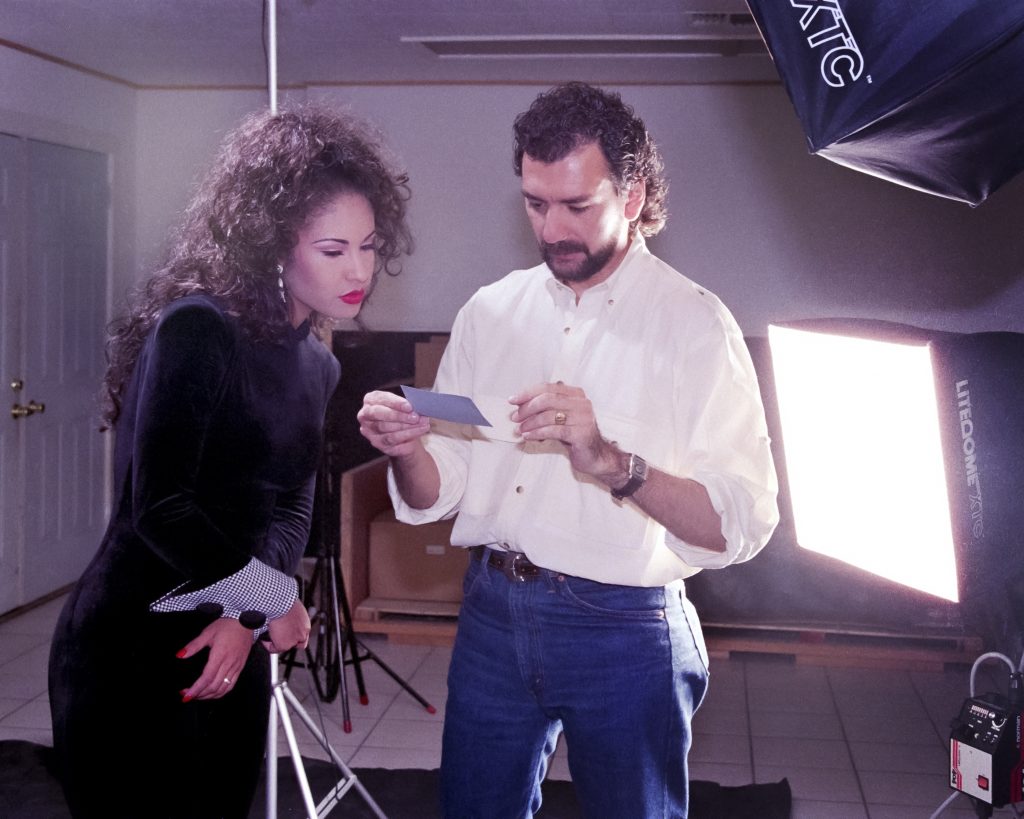

She was La Reina, the Queen of Tejano Music, the rising star and standard-bearer of the regional sound made by Mexican Americans in Texas, a sound that was on the verge of crossing over into the mainstream popular arena. She was all of 22 when I met her — a flower in full bloom, knockout gorgeous, charismatic, and comfortable in her own skin. She was a role model to young Mexican American girls who had precious few role models to look up to. She endorsed Coca-Cola. She was smart, successful, and clearly destined for greatness.

All that promise was cut short on the last day of March 25 years ago, when Selena Quintanilla-Pérez was shot and killed in a crime of passion by Yolanda Saldívar, her fan club president, business associate, and best friend.

The tragedy remains fresh for her longtime fans and, increasingly, for new converts, not all of whom are Mexican Americans in Texas or the Southwest. They are people of all colors, from all walks of life, from all around the world. Many weren’t yet born when Selena was alive. They’ve heard her voice, seen video clips of her storied Astrodome performance, and are drawn to the uplifting life story that ended abruptly in death, darkness, and tragedy.

I know a few things about Selena. As a Texas-based music writer, I had followed her trajectory in Tejano music from captivating teenage singer performing with her sister and brother to the confident young woman who was the biggest star in that musical genre. In the early 1990s, her band, Los Dinos, was selling hundreds of thousands of records, more than even ZZ Top or Willie Nelson.

She was the complete entertainment package: a powerful singer, a physical dancer, a commanding presence on and off stage. Her songs ran the gamut. Ballads such as her biggest English-language hit, “Dreaming of You,” and the story song about forbidden love, “Amor Prohibido,” showcased her exceptional emotional range. Her powerful vocals were the signatures of the crunching cumbia rocker “La Carcacha,” the traditional Mexican ranchera “El Toro Relajo,” and the nonsensical singalong “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom.”

Selena y los Dinos were part of a musical wave — along with the Houston band La Mafia, Grupo Mazz from the Rio Grande Valley of deep South Texas, and Emilio Navaira from San Antonio — that was putting Tejano on the map. She recorded a duet with David Byrne and sang mariachi in a film starring Johnny Depp. Her crossover into pop music — the “general market,” as Mexican Americans call it — was imminent when I interviewed her for Texas Monthly magazine in the spring of 1994.

But as we sat and talked on her tour bus before a show in Austin that night, she seemed more interested in telling me about her Selena Etc. boutiques in San Antonio and her hometown of Corpus Christi and the fashion line she was developing.

The band she performed in — with her producer brother, A.B., on bass and her sister, Suzette, on drums — was her father Abraham’s idea, born out of his inability to crack the big time with his early 1960s doo-wop group, the Dinos. Fashion and the Selena Etc. boutiques were her ideas.

Chatting across the table, she had me mesmerized. Dressed casually in a white sweatshirt and jeans, she was strikingly beautiful without the heavy makeup she always wore in public, animated, and very much in command, hushing father-manager Abraham who was sitting on the nearby sofa with her mom, Marcella, when he interrupted to add to the conversation. After almost an hour, I walked off the bus feeling lightheaded and totally smitten. This woman could do whatever she set her mind to and be whomever she wanted to be. The next Gloria Estefan or the next Madonna? Absolutely. Maybe bigger, from what I could tell.

Nine months later, Selena lay dying in the lobby of the Days Inn in Corpus Christi, her hometown, killed by a bullet fired from a Taurus revolver held by Yolanda Saldívar. The manager of Selena’s boutiques and her constant companion, Saldívar had been accused of stealing money from the fan club and Selena’s businesses, but Selena refused to believe the accusations until shortly before the shooting.

The two had argued in front of Yolanda’s hotel room, and Yolanda shot Selena, who ran toward the lobby seeking help, collapsing by the front desk.

Her sudden death was a cold ending to a too-short life story of grit, determination, and inspiration. Her rise from blue-collar roots, growing up speaking English and learning Spanish and her culture, achieving unprecedented success in a male-dominated field, and serving as a spokesperson for young Hispanic girls is a compelling tale. The tragic twist made her the icon she is today.

Despite the triumphs, “It’s so sad” is the refrain I hear most often from her fans today. She’s become symbolic, a folk heroine like Frida Kahlo. Her records continue to sell, her videos continue to rack up views, and other artists continue to cover her songs, as Kacey Musgraves did when she brought down the house and made front-page news singing “Como la Flor” at the 2019 Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo.

The reaction to Selena’s death in Mexican American communities around South Texas was like the reaction in my hometown of Fort Worth to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas back in 1963. Vehicles turned on their headlights in daylight, “Selena Forever” messages written with white shoe polish on their windshields. Pop-up shrines appeared everywhere — at the Selena Etc. boutiques in San Antonio and Corpus Christi, on the chain-link fence outside the Quintanilla residences in the Molina neighborhood, around the door of Room 158 at the Days Inn where the shooting occurred. People walked around dazed and shell-shocked, like a bomb had gone off and they didn’t know what to do.

The posthumous album Dreaming of You was the bestselling Latin album of 1995 and 1996, moving almost 3 million copies. People magazine and Texas Monthly set record newsstand sales with Selena covers. I wrote a book, Selena: Como la Flor, one of several written about Selena. That led to a live appearance on the Univision talk show El Show de Cristina (Cristina Saralegui being the Oprah of Latin America) along with other Selena authors. At the end of the program, a Puerto Rican book critic declared my book to be the only legitimate biography; the other books trafficked in rumors, myth, and speculation, the book critic said.

The day after the Cristina appearance, I returned to work at Texas Monthly. No one there seemed aware of my turn on Spanish-language TV except the cleaning lady, who buttonholed me in the commissary and with wide-open eyes and a big smile exclaimed, “I saw you on Cristina!” The largely Anglo staff of Texas Monthly had no clue.

The 1997 music biopic Selena, with Jennifer Lopez in an early star-making role and Edward James Olmos playing a credible Abraham Quintanilla, remains the most popular entry point for people discovering Selena, even more than her recordings. Box Office Mojo ranks it as the 15th highest-grossing musical biopic of all time.

She would have been 49 this April. Twenty-five years after her death, Selena is bigger than ever.

The Selena makeup collection, a joint venture between MAC Cosmetics and the Quintanilla family, flew off the shelves when the line was introduced in 2016. Selena: The Series (“the official story of Selena,” starring Christian Serratos) is airing on Netflix. The telenovela El Secreto de Selena, adapted from the book by TV personality María Celeste Arrarás, who covered the Selena trial, aired on Telemundo.

I sensed the groundswell in the fall of 2018, at an event at the Guadalupe Theater in San Antonio. CNN’s sister network HLN had organized a forum to coincide with the airing of a Selena special. HLN had filmed me at my home and then invited me to the Guadalupe to share the stage with Carlos Valdez, the Nueces County District Attorney who successfully prosecuted Yolanda Saldívar. (Convicted of first-degree murder, Saldívar, a former registered nurse who at 59 remains incarcerated in Gatesville, Texas, will be eligible for parole in five years.) Retired from public life, Valdez travels around Mexico as a consultant, explaining the American legal justice system to prosecutors and judges.

Laurie Castro Camacho, a 48-year-old woman from Goliad, Texas, with a bubbly personality not unlike Selena’s, asked Valdez and me to pose for photographs with her, as several people did that night. She told me about how Selena’s image on an album cover caught her attention in 1992 before she’d heard her music. “I just felt she had the ‘it,’ ” Camacho said. And she still did. “Hearing her makes you feel like she is alive. I made the trip to her museum two years ago and I felt her presence. Her last concert was playing on a large TV screen and I started singing along. I got goosebumps. My eyes filled up with tears. Something she said came to mind: ‘The idea is not to live forever but to create something that will.’ I had a knot in my throat. In my mind my response was ... You have, Selena, you have.”

Joe Ojeda, the keyboardist for Los Dinos, and Pete Astudillo, the band’s featured male vocalist and composer, drove up from Laredo for the CNN event. Both were still performing, they told me, but their smiles vanished when I asked if playing now was like it was with Selena. No way. But no matter where and when they played live, Astudillo and Ojeda said, they always carved out a few songs for Selena. The crowd wanted it. They wanted it.

I’d run into Astudillo a year earlier at a fundraiser in Austin where he was a featured guest performing with Stephanie Bergara, leader of the tribute band Bidi Bidi Banda.”

Bergara intrigued me. A City of Austin program coordinator who had worked for managers, booking agents, studio managers, and publicists, she had gotten together with nine musician friends to make Selena music informally five years before, and the band blew up into a thing.

The daughter of blue-collar second-generation Mexican American parents, Bergara was raised on Tejano music. She was inspired to sing by Selena’s ballad “No Me Queda Más.” Bergara, who had been raised speaking primarily English, asked her mother to translate the lyrics, “so I would know where to emote. There is not a show when I sing that song that tears don’t start.”

Seeing Selena on TV changed Bergara’s life. “Selena was the first person who I ever saw on television who looked like she could be related to me,” she said. “She was so sparkly and amazing. I wanted to be onstage singing, just like her. I didn’t know how I was going to do it, but I said to myself, That’s it. That’s what I want to do with my life. I want to be like her.”

Bergara’s band rehearsed six songs for three weeks, then played the Empire Control Room in downtown Austin to a packed house. “I knew how much I loved Selena,” Bergara said. “I had this hope other people loved her as much as I did.”

Bidi Bidi Banda’s tribute repertoire now includes several dozen songs. “If you want to come to a Selena dance party, my seven-piece band has worked very hard to replicate these songs,” Bergara said. “They play them as close to the original as possible. I want people to come to our show, close their eyes, and believe that they’re at a Selena show.”

For Bergara, it’s tragic to think that the Queen of Tejano is remembered more now than celebrated when she was alive. “We played a private event for Google last night. Someone showed up in a Selena T-shirt. She’s as big as she ever was.”

Martin Gomez, who was Selena’s designer for both her stage wear and the fashion line that was in development at the time of her death, reached out to me last spring. He wanted to write a book about his work with Selena and sought my advice. Gomez was the one who went to Selena’s father to warn him about Yolanda Saldívar’s erratic behavior and failure to pay for employees’ insurance and other expenses for Selena’s fan club and businesses; Abraham’s subsequent investigation uncovered evidence Saldívar was stealing from Selena. For close to a month, Selena refused to believe the accusations. She was meeting Saldívar at the Days Inn to retrieve financial records when Saldívar shot her. Gomez had had virtually no contact with the Quintanilla family since her murder, all the while wondering if Selena might still be alive if he hadn’t exposed Saldívar’s embezzling.

Gomez and I met just north of San Antonio in the tourist town of Gruene. Now an executive with the Ascena Retail Group, he wanted to set the record straight. “I was her fashion designer,” he said. “Selena wasn’t designing; I designed the product. It was just her and me doing it. It was the first celebrity brand of its kind.”

Gomez had just reconnected with the Quintanilla family. He had thought the family was mad at him, since he wasn’t chosen to design costumes for the Selena film. He learned the family thought he’d moved on to pursue his fashion career at Dillard’s.

“It lifted a burden for me, realizing we’re all in a different place,” Gomez said. The best part was seeing his costumes displayed in the Selena Museum, part of Abraham’s Q Productions headquarters in Corpus Christi. “I hadn’t seen them since the last time she wore them,” Gomez said.

“It was super emotional. But going back wasn’t cathartic. It was just sad. Someone was completely cheated of greatness. I’ve moved on and enjoyed an extremely successful and lucrative career in design and fashion. She and I had conversations about going to Fashion Week in Paris. I got to live that. She did not.”

Gomez thinks Selena’s legacy has grown for all the right reasons. “When you see interviews of her, you see she was truly a sweet young woman, a nice girl. She said, ‘I don’t want to intentionally hurt anyone. I don’t want to hurt people’s feelings.’ People are fascinated with that legend. My Facebook is bombarded with Selena fans in their 20s and teens. They weren’t around and don’t really know. They grew up with the movie. They only know the performer they see on YouTube.”

Because of that, Gomez believes, Selena’s eye for innovation in fashion and design has been overlooked. “People today are missing that this girl was more than a singer and performer. She was a visionary. Jennifer Lopez took what Selena was doing and used it as a road map. It’s hard to create a new idea in fashion. I know that now. And back in 1993, Selena had this new idea.”

On a sunny picture-perfect October day, I retraced the path I’d taken two days after Selena’s death, driving 198 miles from my house in the Texas Hill Country to Corpus Christi, exiting right on Peoples Street. The Days Inn where Selena was shot was the Knights Inn now, hidden behind a newer Hampton Inn and newer Holiday Inn Express.

I had been in Corpus Christi several times over the past 25 years, but I hadn’t been to Selena’s Corpus Christi since my book tour.

In those days immediately after Selena’s death, a scattering of fans had placed wreaths and improvised a shrine outside the room where she was shot, while others pored over the St. Augustine grass by the pool, some on hands and knees, examining her path from Room 158 to the lobby, clutching in her hand the ring that Saldívar had bought for her with money skimmed from Selena’s businesses.

The motel had aged through multiple exterior paint jobs. The front desk and lobby had been refashioned into the Las Milpas Restaurant. The pool looked the same. The Washington palms hovered above the property stately and beautiful as ever, but fixtures appeared well-used and tired.

You could say the same for the city. Despite downtown additions like the Whataburger Field ballpark and the American Bank Center arena, the town otherwise looked like the refinery port it is. Whataburger, Corpus’ best-known brand besides Selena, had moved its corporate headquarters to San Antonio.

At the Visitor Information Center downtown, an older Anglo woman at the front desk drew two circles on a giveaway city map to show the city’s Selena sites: the Selena memorial on Shoreline Boulevard and the Selena Museum at Q Productions at 5410 Leopard St. “It’s a warehouse-looking building in an industrial area,” she said. “That’s a working recording studio there as well as a small museum. Admission is $3.”

Anywhere else? The lady paused, then offered directions to the gravesite at Seaside Memorial Park & Funeral Home on Ocean Drive.

“What about the Selena Auditorium? Is there a marker there?”

The lady didn’t know, but I was only a block away and I could probably double-park near the loading area to see for myself. “But I didn’t tell you that,” she said, smiling impishly.

I drove over to the American Bank Center, double-parked near the loading area with my flashers on, and went inside.

The venue where Selena y Los Dinos had performed and where Selena’s body lay in state for public viewing was now the Selena Auditorium, attached to a convention center and 10,000-seat arena. The old Bayfront Plaza Auditorium was renamed in 1996 and had been updated twice since. A large full-body oil portrait of Selena, singing with her eyes closed, hung prominently on a column in the high-ceilinged lobby outside the 2,500-seat venue, along with a brief explanation of her life: “Dedicated in memory of Selena Quintanilla-Pérez, the American Bank Center Selena Auditorium will forever serve as a reminder of all that Selena achieved as an entertainer and a remarkable human being. With dignity and kindness she touched our hearts. With music she touched our souls.”

Eight blocks down Shoreline by the bayfront seawall, 15 people milled around a modified gazebo in the midafternoon sun. This was the Selena Memorial — Mirador de la Flor (Overlook of the Flower) — by the Peoples Saint T-Head and the Corpus Christi Marina. Dedicated in 1997, the memorial’s centerpiece is a life-size bronze of Selena wearing a short jacket, blouse, jeans, and boots, leaning comfortably against the gazebo’s main column, one leg propped back. On the other side of the column is a sculpted rose. A recorded voice briefly told Selena’s story in English and in Spanish.

Many of the bricks surrounding the sculpture bore the names of donors who helped pay for the memorial. Others were decorated with hand-scrawled signatures of fans who had made the pilgrimage, a disproportionate number of visitors from Jalisco State in Mexico.

Three women — all Mexican American — took selfie photos at the statue. When I started to take a photo of them taking photos, one told the others in Spanish to move.

“It’s OK,” I said. “I want to have people in the photo.” A woman in her 50s grinned and started talking to me in English: “I saw her in El Paso when she was just starting out. She was so talented and so good. I felt it immediately. When my daughter started listening to her, she really got into her music big time. I said, ‘How can you like her? You never saw her.’ But she does.”

The woman shook her head as she turned to leave. “Yeah, it’s so sad.”

A thin elderly Hispanic man pushed a teenaged girl in a wheelchair up to the statue and both looked up somberly. As I walked away, an Anglo woman who appeared to have seen better days approached with a question: “Got a cigarette?”

I cruised Ocean Drive to the Seaside Memorial Park & Funeral Home, passing the fanciest homes in the city. Somehow, I knew where to go, even though the gravesite had changed. A concrete walkway led from the roadside curb to a low black-iron fence that had been erected around the grave. A small sign at the gate read: “Stay Out: Respect Gravesite.”

The headstone with the familiar Selena script logo loomed behind a bronze head-and-shoulders likeness of Selena that covered the headstone on her actual grave. Behind the headstone, a planted mesquite tree, the iconic tree of South Texas, had grown large enough to provide protective shade.

A plaque identified Selena Quintanilla-Pérez, followed by a Bible passage from Isaiah 25:8, written in English and Spanish. And there were white roses — the singer’s favorite — left by pilgrim fans. Como la Flor — like the flower.

Three women, two men, and two children walked to the gate and paused. “We’re from Alice,” a woman in her 30s volunteered. “Our grandmother is over there. We haven’t been to see her in almost a year,” she said apologetically. “So we came to see Selena. I wonder how often her family comes here.”

The group paid their respects. The only sounds were the steady breezes coming in from the Gulf and the whirrs, whistles, and clicks of shiny black grackles perched in the branches of the mesquite.

The sounds were eternal. Nothing else seemed what it once was.

The Selena Etc. Boutique and Salon by the mall had closed. The record shop where Abraham Quintanilla was mentored by Johnny Herrera, a singer and performer from the 1950s known as El Suspiro de las Damas (The Heartthrob) — gone.

On the other hand, La Molina — the working-class neighborhood where Selena and her husband, Chris Pérez, lived in a brick house in between her parents’ brick house and her sister and her sister’s husband’s brick house on one small lot — looked neater and tidier than it did 25 years ago, like the community had grown even more tightknit. The simple bungalows were humble but well-kept. Molina looked like a neighborhood where everyone knew everyone else.

No signage identified the three houses at the end of Bloomington Street as Quintanilla property or Selena’s last residence (although she and Chris had bought property outside of Corpus and planned to move there “to raise chickens and babies,” she had told me).

A couple of blocks down at the corner of Elvira Drive, a Selena mural with three of her likenesses that was painted in 2019 covered the street-side wall of the Food Store.

I drove over to Leopard Street and slowed by the entrance to the Selena Museum and Q Productions, a metal building housing a recording studio and museum behind a black iron gate topped by three strands of barbed wire. Ten people mingled around the parking area in front of the building. At the back of the lot were trucks and the tour bus, as if Los Dinos were preparing to go out on the road again.

I had been to Q Productions to interview Abraham three days after his daughter’s death. We hugged at the end. For a brief period, he suggested we collaborate on a book, but the deal fell apart when he began to dictate what could and couldn’t be said (he declared her Jehovah’s Witnesses faith off-limits).

This time, though, after pausing, I drove on. Too many ghosts were inside that fence, too many dark memories. It’s time to move on, I thought to myself.

Fat chance. On the way out of Corpus Christi, a billboard on Interstate 37 caught my eye: The Bee County Coliseum in nearby Beeville was presenting Karla Pérez and Selena, The Show. I switched on the radio and “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” came on. I turned up the volume and pressed on the accelerator.

Not surprisingly, Selena stayed with me all the way home.

Photography: Courtesy Al Rendon

From our February/March 2020 issue.