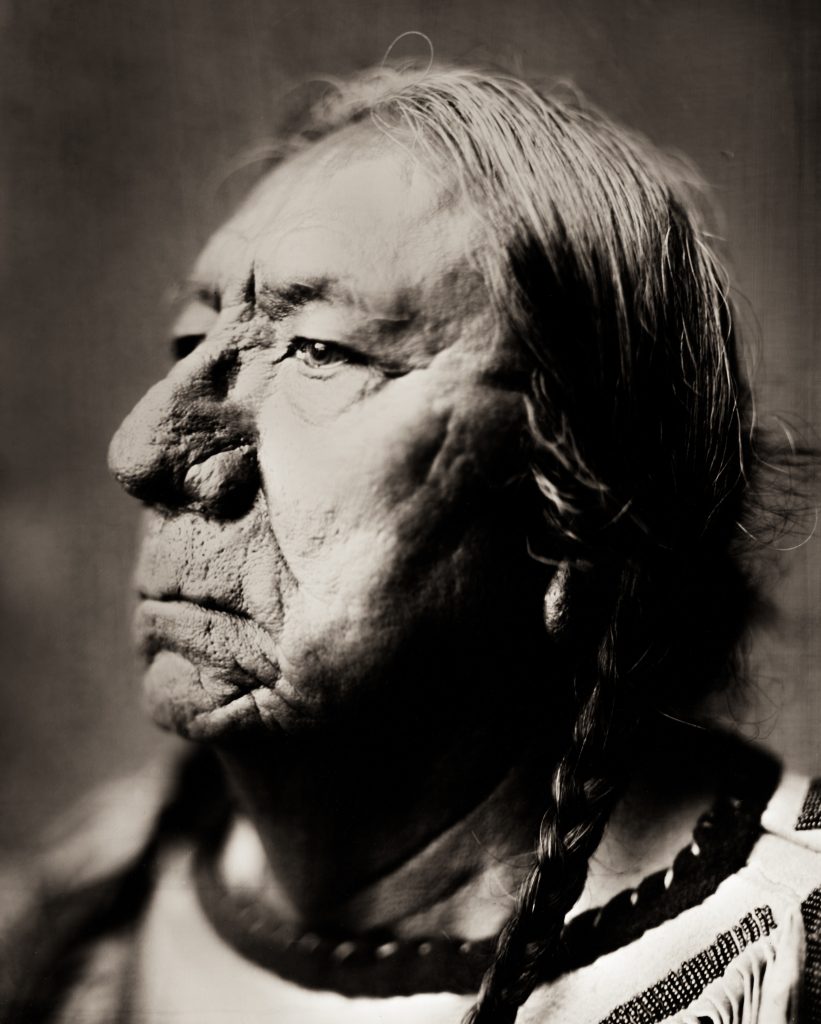

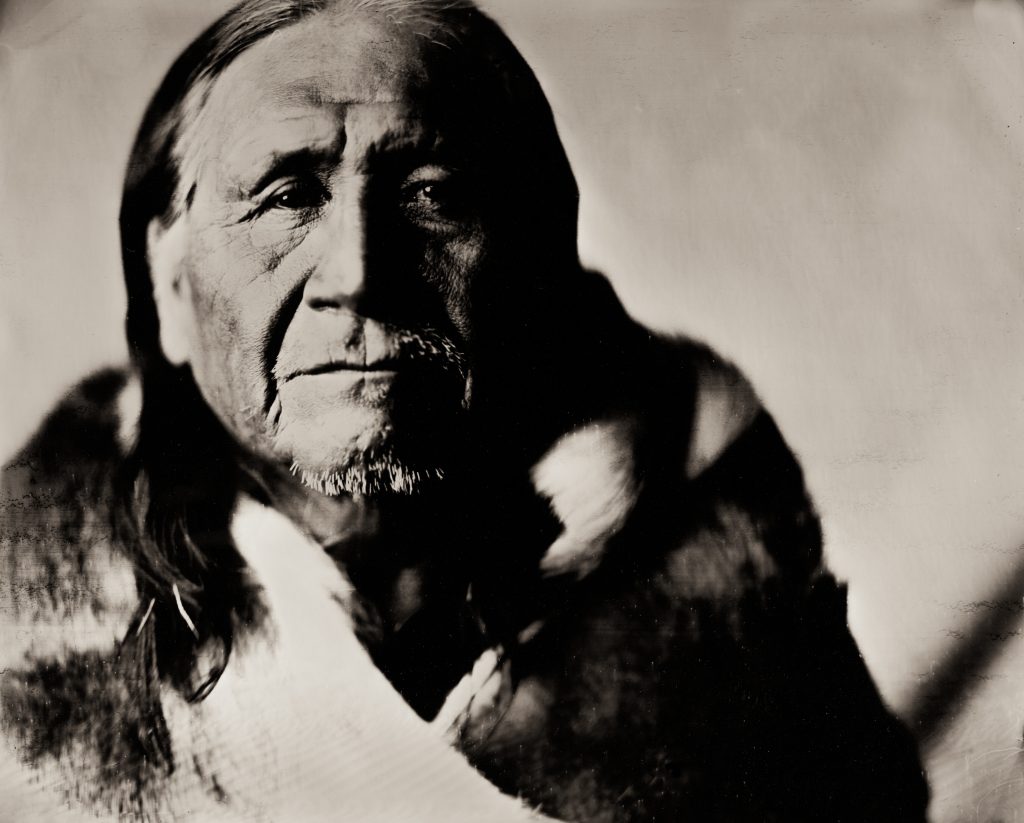

Photographer Shane Balkowitsch celebrates the modern faces of Native America using an Old West technique.

Shane Balkowitsch didn’t foresee the way history would come circling back around when he constructed what is probably the country’s first new natural-light, wet-plate photography studio built in more than a century.

He began to figure it out when Ernie LaPointe came to pose for a portrait in September 2014.

For a photographer persevering in a cumbersome technique invented in 1851 that nevertheless creates lasting images of incredibly fine detail, the chance to do that portrait brought to mind the work of an earlier photographer whom Balkowitsch reveres.

“Orlando Scott Goff was a wet-plate artist here in Bismarck, North Dakota, and he captured this image, which was the first image ever taken of Sitting Bull. One hundred and thirty-five years later, I captured Ernie LaPointe, the great-grandson of Sitting Bull, in the same process in the same city,” Balkowitsch says from his Nostalgic Glass Wet Plate Studio in Bismarck. “That’s portrait No. 1 for the series.”

The series Balkowitsch is referring to took shape soon after LaPointe sat for that portrait. Looking at the face of Sitting Bull’s great-grandson, Balkowitsch realized that one key aspect of the work of Goff and other early frontier photographers taking portraits of Native Americans was unfinished business. There was room for a 21st-century treatment.

Balkowitsch came up with the idea of doing 1,000 portraits of Native Americans. From each set of 250 portraits, he plans to publish a book of 50. His first set led to the first book of an eventual three-volume project, Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective, Artist Edition, Volume 1, published in May 2019, followed in October by a trade version put out by New York-based Glitterati Editions. A portion of the sales of the book and prints from the series benefit the American Indian College Fund.

Just as 19th-century photographers did, Balkowitsch depends on natural light for his portraits — no flash, and no studio lights unless the sun won’t cooperate. At his suggestion, subjects bring whatever regalia or objects they want in the photograph. Using a stand or brace to keep their heads still for the several seconds needed to take a photograph, he tells them to think of something important to them while they wait out the 10-second exposure so that, ideally, some sense of who they are might come through in the portrait.

Remarkably, Balkowitsch was not a photographer before 2012. He never took a class and had no formal training. But he became fascinated with wet-plate collodion photography, a chemical-laden process developed by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851. While Balkowitsch substitutes at least one chemical for a safer modern alternative, he follows essentially the same method popularized in the mid-19th century. But it’s not for a love of things retro. “There’s nothing backward about this,” he says. “These are some of the highest-resolution images ever made. What you see is pure silver on glass. What’s beautiful about pure silver is its archivability. All these inks and pigments and paints and dyes that we use, they all fail us over time. This will be here a thousand years from now, unbroken.”

It’s for that reason that early wet-plate photographers called themselves ambrotypists, a term coined from the Greek words for “immortal” and “impression.” That’s the term Balkowitsch still uses for himself on his business cards: Shane Balkowitsch, Ambrotypist.

“There’s been kind of a revitalization of the process. There’s about a thousand of us in the world presently that are practicing,” he says. “I do it for history, knowing these images will be here long after I leave this earth.”

The State Historical Society of North Dakota is already archiving his Native American images as valuable historical records of 21st-century people.

Although Native American portraits are a main focus of his work, Balkowitsch will photograph anyone who will wait out the 30-minute preparation of the wet plate and then sit still for the 10-second exposure. The complex process requires that he do most of his work in his Bismarck studio, where he has received some notable subjects. One of his studio images — of former world heavyweight boxing champion Evander Holyfield — is in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. But Balkowitsch can go mobile, as he did last October when he dashed down to the Standing Rock Indian Reservation with his portable darkroom to make a portrait of Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg.

As gratifying as those high-profile shots might be, one honor surpasses them all: The Hidatsa held a ceremony and gave him a name in their language. They called him Maa’ishda tehxixi Agu’agshi — “Shadow Catcher,” which Balkowitsch calls “the greatest honor of my life.”

Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective (Glitterati Editions) is available on amazon.com. Visit Shane Balkowitsch at sharoncol.balkowitsch.com/wetplate.htm

Photography: Courtesy South Dakota State Historical Society

From our February/March 2020 issue.