He’s worn many hats, but his latest acting highlights are contributing to a stunning career renaissance.

Maybe you still identify him as Billy Black, the wheelchair-bound father of a young Quileute who moonlights as a werewolf, in the Twilight Saga movies. Or perhaps you recognize him primarily for his arresting supporting performances in the critically acclaimed films Hell or High Water and Wind River. Or maybe he’s most familiar to you for TV credits that range from heavy drama (Banshee, House of Cards) to wacky sitcom (Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt) to fanciful fantasy (Siren).

But it’s more than likely that, very soon, you and millions of other folks will know Gil Birmingham best as Thomas Rainwater, an influential tribal chief, community leader, and political string-puller who clashes with John Dutton (Kevin Costner), the powerful paterfamilias of a Montana ranching dynasty, in Yellowstone, the new Paramount Network series created and overseen by director and Oscar-nominated (for Hell or High Water) screenwriter Taylor Sheridan.

During a key scene in the series’ premiere episode, Rainwater makes a forceful first impression while simultaneously revealing his roots and unveiling his ambitions: As a tribal elder meticulously performs a ceremonial “cleansing” in his office overlooking his lavish casino, he shares with a well-connected visitor his plans to reclaim, by any means necessary, the land stolen from his people long ago by interlopers like the Duttons. Birmingham deftly sells every word, every gesture, as his character indelibly establishes himself as a force to be reckoned with.

“Oh, boy, did I love doing that monologue. ‘There isn’t a hill that you’ve skied or a road that you’ve traveled that didn’t belong to my people first.’ Like, now they want to give it back? Hell, we’ll buy it back, with their money. Yeah.”

Birmingham is speaking, and smiling broadly, while seated in his favorite Redondo Beach, California, restaurant for a late-morning chat. It’s a place he has frequented since the days when he pursued bodybuilding as an art, a period when he slowly drifted from steady yet unsatisfying employment as an engineer designer to a relatively late-blooming and recently high-profile acting career. (The menu, it should be noted, contains a “Beach Body Fitness” list of entrees under 600 calories.) Even so, you get the impression while speaking with him that, except when he’s fielding questions from interviewers, he’s not stuck in the past, or even overly prone to nostalgia. He’s too busy looking forward.

At the ripe young age of 64, Birmingham appears poised to make the transition from journeyman actor to household name. He currently has continuing roles in two television series — when he’s not looming large in Yellowstone, he’s the police chief of a community where mermaids are more than mere legends in Siren — and sporadically appears in two others (Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, Animal Kingdom). Hell or High Water (which cast him as the stoic partner of Texas Ranger Jeff Bridges) and Wind River (in which he plays the grieving father of a murder victim tracked by Jeremy Renner) remain in heavy rotation on cable and streaming platforms. And there has been talk of other future projects that can’t yet be discussed while an interviewer’s audio recorder is running.

On those occasions when Birmingham is encouraged to take backward glances, he speaks bluntly and unsentimentally. A native of San Antonio, Texas, he was born to a Comanche father and a mother of Spanish ancestry, and moved around a lot because of his father’s Army career. He describes his parents as something less than nurturing, and something else far from forthcoming: Until he reached his teens, he was led to believe he and his family were Spanish, Mexican, and English, because his father didn’t want him to endure the kind of prejudice often directed at Native Americans. (More on that later.) He frequently ran away from home, eventually wound up in foster care, and attended the University of Southern California only because “I was lucky enough to encounter a school counselor about the age of 18 who said, ‘We’ll provide housing for you, you know? And you can go to college.’ And that changed my life.”

Birmingham changed his life again when, after five years of what he describes as “soulless” work as a petrochemical engineer, he kinda-sorta backed into acting — even though he took no drama classes whatsoever at USC — and began a second career that started with an apprenticeship as music video bit player and theme park performer, and continues today with ever-increasing exposure in prime time and on big screens. And, yes, with the occasional celebrity interview.

Here are some highlights from our conversation, edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Cowboys & Indians: So just who is Yellowstone’s Thomas Rainwater? And what does he want?

Gil Birmingham: What does Thomas Rainwater want? Respect, justice, and equality for his people. The ironic thing is, as Taylor Sheridan wrote him — which is so brilliant — he didn’t come to find out that he actually was Native for a long time. And now that’s part of his motivation. His parents had told him he was Mexican, figuring that would shield him against the prejudice he might experience as a Native. What he witnessed after that point of discovering that he was Native, and why it was so important for his parents to lie to him about that in order to protect him — that’s what I feel really initiated Thomas Rainwater’s having a “woke” moment about what the conditions of the world are, and his relationship to that world. The more he got integrated into learning his Native culture, the more respect he had for it, the more it made sense to him.

C&I: And you obviously could relate to that.

Birmingham: Yeah, it’s pretty synchronized, because I didn’t find out I was Native until I was 14. My parents did the same thing to me. And they did it for the same reasons. In my estimation, people who do that sort of thing try to operate in a covert way that reduces the pain in their life and, hopefully, the pain in their children’s life. But you have to buy into some other kind of philosophical or spiritual belief for that to make sense for you. My father bought into it with the strictness of the military. He defined himself as a military career man. That spoke to him in terms of having order in his life. And having some sense of equality — at least, in his mind. My mother used religion. They were both using substitutes rather than engaging in anything that spoke to their real ancestry. So when I read this script and I read that monologue where Thomas Rainwater reveals that about himself — well, I mean, sometimes things just blow your mind.

C&I: You took an indirect route to acting. In fact, after you graduated from the University of Southern California, you worked for a long stretch in the ’80s as an engineer designer. But somewhere along the line, you became — a bodybuilder?

Birmingham: [Laughs.] Well, you know when you’re younger, you’re not really sure why the things that speak to you do so, or how to figure them out. Especially in a world that’s really constantly focusing you on a different value system, you know? Like making a living, developing some kind of skill that you can operate in the value system. But at the same time, it’s so artificial. And it’s so unsustainable. And it’s so destructive in the sense that the value system is about acquisition and money and values, about having some level of status.

In my case, I felt I needed to find some way to express myself, to create. At first, it was music. When I picked up a guitar, I thought, This is me. This is what my expression is. And later, I started viewing bodybuilding that way. I was fascinated that you could sculpt a body like a piece of sculpture.

C&I: One of your first acting gigs was playing Conan the Barbarian — the action hero character that helped make Arnold Schwarzenegger a movie superstar — at the Universal Studios theme park here in Los Angeles. But even before that, when you first got interested in bodybuilding, did Schwarzenegger’s early fame and success in that area have any influence on you?

Birmingham: It did, I guess, but it was isolated to just the artistic view I had of bodybuilding. I didn’t have a dream of becoming a bodybuilder so I could become an actor. I never even dreamt of being an actor.

But here’s the funny thing: I got scouted in the gym — the same gym where Arnold Schwarzenegger worked out — to be in a Diana Ross music video [“Muscles”]. And I had so much fun on the set. My girlfriend at the time had moved from Hawaii to try to be an actress here in LA. She was studying acting, taking classes, and she said, “Well, why don’t you start studying?” And I said, “Hey, I don’t know. I don’t really have a direction going right now — let’s see what this acting thing’s about.”

C&I: Was it difficult for you to make that switch? To move from having a steady income as an engineer designer to scratching by as a struggling actor?

Birmingham: Not really. When I was young, I ran away from home about six or seven times. And the court always just returned me back to my parents. And I remember one time in particular, when I was getting less and less able to tolerate things at home, I ran away. The only thing I took with me was my guitar. And it was raining and it was pouring and it was cold. And I would get on a bus and stay on it as long as I could until the bus driver would say, “This is the end of the route. Stay warm.” I slept under stairwells in apartment complexes. Yet I never felt freer. And the freedom was more important to me than the comfort.

When I say freedom, it was freedom of soul, freedom of spirit. It was a case of the possibilities superseding any fear about how I was gonna be able to stay alive. I came from very meager beginnings to begin with. Military pay is not much. And my dad had five kids. I mean, we weren’t extremely poor. But we weren’t well-off by any means. So I had already adjusted. Going through college was the same thing. I’m still a minimalist. I don’t really need a lot of things. And the more things I think I want to purchase, the more it feels counter to the level of consumption that I think serves me.

C&I: Looking back, what were some of the toughest things to learn about acting?

Birmingham: That’s a really interesting question. At the first classes I took, there was [an acting coach] named Charles Conrad, and he really followed the Sanford Meisner technique. And one of the things that got impressed upon you at that time in acting class was that you always had to feel the stakes were high in whatever you were doing. But in my case, by the time I got a small part as a traffic cop in an episode of Riptide, I had all this intensity about me. All the character had to do is just pull these guys over. But I thought, OK, how am I gonna make this a life-and-death thing? So I did several takes. And God bless our director, he had to work around this seething thing that I did. Afterward, when I saw the final cut, I thought, Well, they’re sure not cutting to me very much.

C&I: So you had to learn to relax?

Birmingham: The beautiful thing is I was able to dial into how close music is to acting in television and film. When I’m playing music, I’m lost in it. There isn’t self-conscious thought. It’s a stream-of-consciousness thing that occurs, and that helps you free yourself in order to be available as a vehicle. I think the first time where this really hit me was Into the West.

C&I: That was the epic Steven Spielberg miniseries about the interactions between white settlers and Native Americans during the settling of the American West.

Birmingham: Right. That’s when I realized that what I was doing wasn’t just entertainment. It’s also a responsibility. That made a powerful impact on me. But it was liberating at the same time, because it freed me from the idea that this was all about me. This has nothing to do with me. This has to do with your ability to be a vehicle, so you can convey, in the most respectful and fruitful way, universal experiences. Sometimes experiences that you can’t even really fathom. But things that you know human beings really experience.

C&I: Throughout your career, you have played several Native American characters, real and fictional, in period dramas. But it seems that recently you’ve gravitated toward more contemporary stories.

Birmingham: I guess it’s my way of saying, “Listen, the progression needs to be more contemporary. Not every Native American lives on a reservation. We don’t live in tepees anymore. We’re not just historical people that were defeated as a result of settlers coming in and deciding, ‘We will do whatever we have to do to acquire all the lands that we want.’ ” So I had consciously put it out to the universe, I guess, that I wanted to do more contemporary roles. Of course, this wasn’t necessarily a choice I was gonna have unless either I wrote my own, or I was gonna make movies, which wasn’t my forte. [Laughs.] But fortunately, there’s been somewhat of a renaissance — a Native renaissance.

C&I: Since Twilight, you’ve played a wide variety of roles in an exceptionally diverse array of projects. Everything from heavy dramas like Hell or High Water and Wind River to zany comedy like Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt.

Birmingham: I think Hell or High Water was the big turning point there. You know, if you’re lucky enough to get any kind of success in this business, it’s an incredible blessing, because the majority of people never get it. The most important ingredient that you have to have with [an acting career] is perseverance, the ability to stick with it. But it’s sometimes bittersweet, because to be able to stick with it through so many years requires so many sacrifices. Unending disappointment and rejection, heartbreak, self-doubt. Really, a sense of not being in control of your life, you know?

I don’t know how it is that we try to diminish the painful aspects of our journey, versus the success part of it. People have told me, “Listen, you’re at this grand level now.” And I don’t know if I would say I’m a cynic, but I do feel like I’m a realist. And I go, “OK, I have a higher profile. But I had a higher profile in a movie saga called Twilight than I did in a critically acclaimed film like Hell or High Water or Wind River. Far more people ... saw [the Twilight movies], and attach my name to that.” And not to take away from Twilight, but it didn’t speak to my heart the way the projects I’ve done more recently have. Projects with great writing and really interesting character studies. That is what all actors want to sink their teeth into. The indie movies, the things that aren’t going to be controlled by a studio or made by committee. It’s been a curious thing to kind of have both sides of those experiences. Like, with Twilight, there were screaming fans and premieres and stuff. And you might think, “Oh, wow. Look, I made it.” Really? Well you know, as soon as Hunger Games comes along, hey, they forget you.

C&I: It seems like every few years, there’s a lot of loose talk about how more movies are being made about Native Americans, or with Native American characters. But as you said, it really does seem like we’re in the middle of a Native renaissance.

Birmingham: Somehow, in a spiritual sense, I feel like I’ve been guided to be at the place where I’m at, with the projects that have come to me. Which has also been liberating, because it’s very competitive in Hollywood. And for all these many years that I’ve been in it — there have been friends of mine, and we’re buddies and all that, but we’re all competing for the same limited number of jobs. And I think that’s where some of the self-doubt comes in. And you go, “Why did they get that? I could have done that.” And now you can relax and go, “You know, everybody is getting exactly what they’re supposed to get.” And the more everybody flourishes, the better. At this point, it’s a joy to watch the next generation coming up. You know, they just announced yesterday that Martin Sensmeier is gonna be playing Jim Thorpe in Bright Path: The Jim Thorpe Story.

C&I: And with all due respect to Burt Lancaster, who played the title role in that 1951 biopic Jim Thorpe — All American, it’s nice to see an iconic Native American being played by, well, an actual Native American.

Birmingham: [Laughs.] That’s huge. I mean, that’s the thing that we’ve always wanted to do — to be able to integrate our stories into the mainstream, so people can learn. And be entertained. And, you know, be inspired.

Yellowstone is currently airing on the Paramount Network. Check your cable listings or stream on their website.

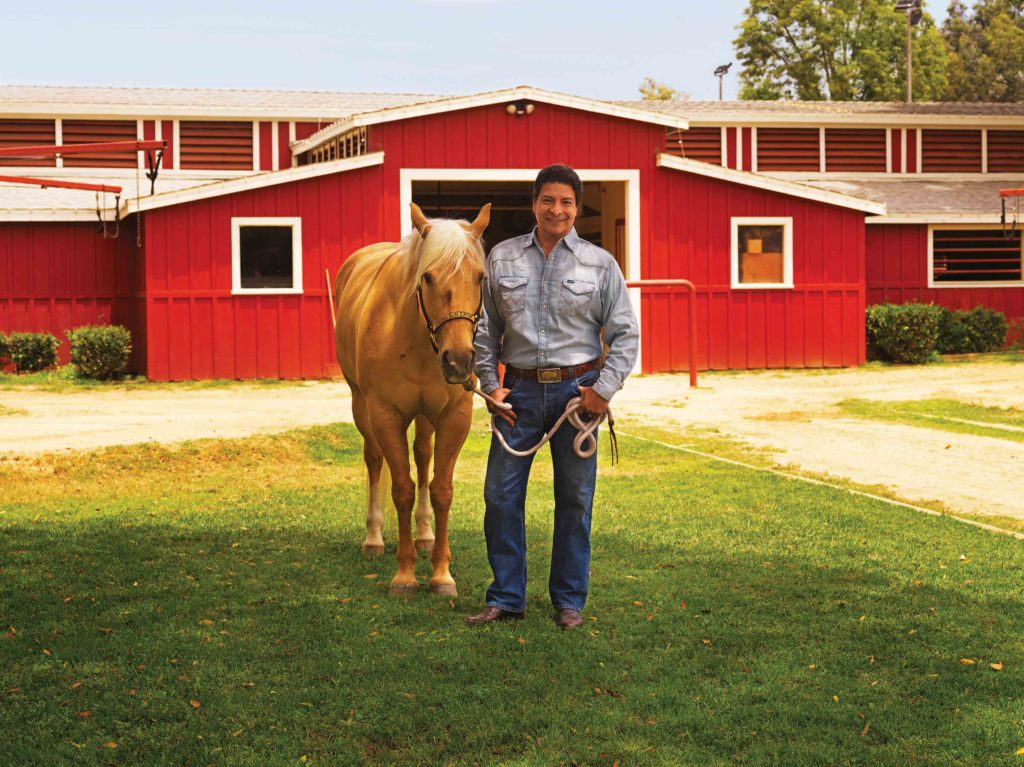

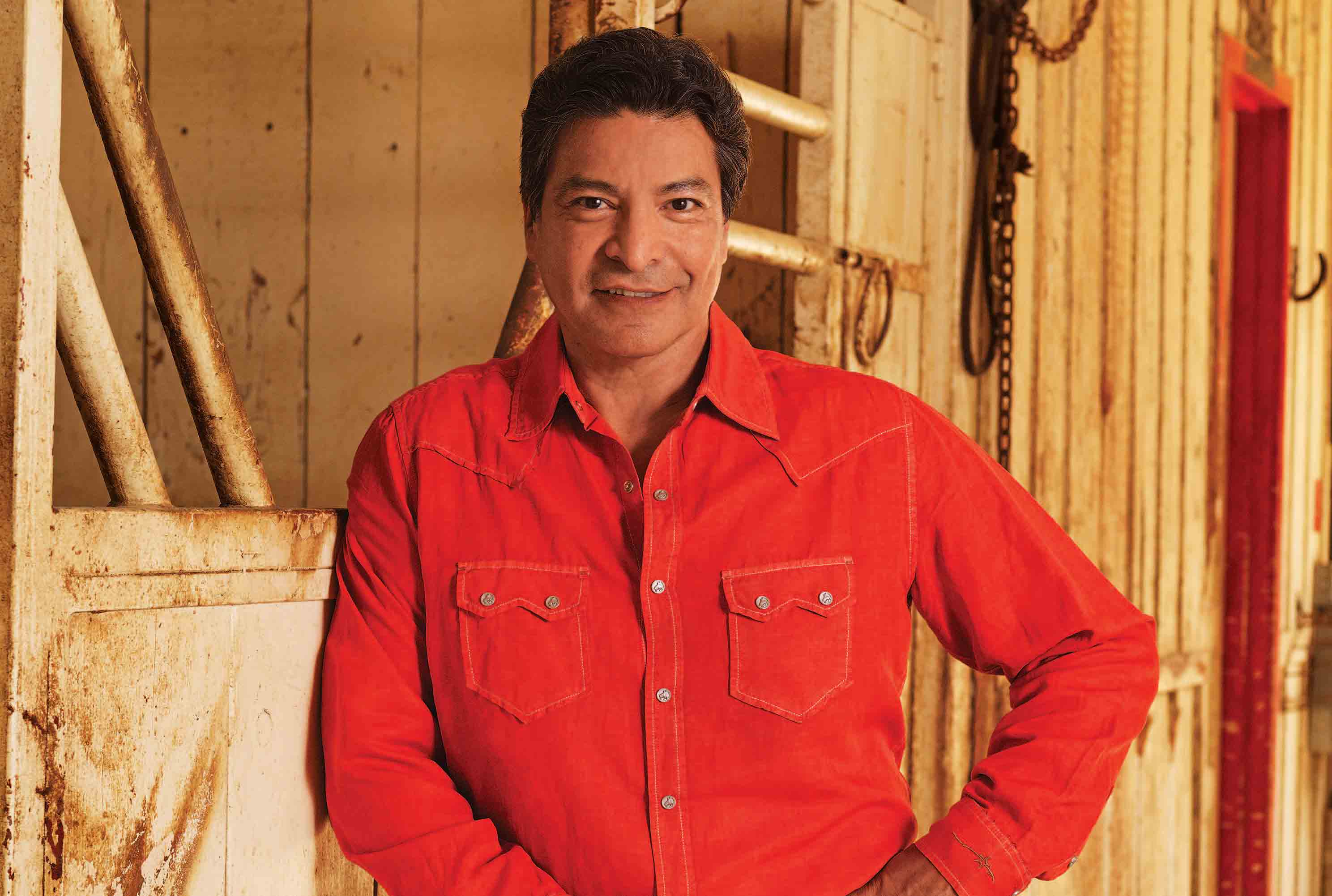

Lead Article Photo - Photography: Emerson Miller/Courtesy Paramount Network

From the August/September 2018 issue.

More Yellowstone

Kevin Costner

Preview: Kevin Costner in Yellowstone