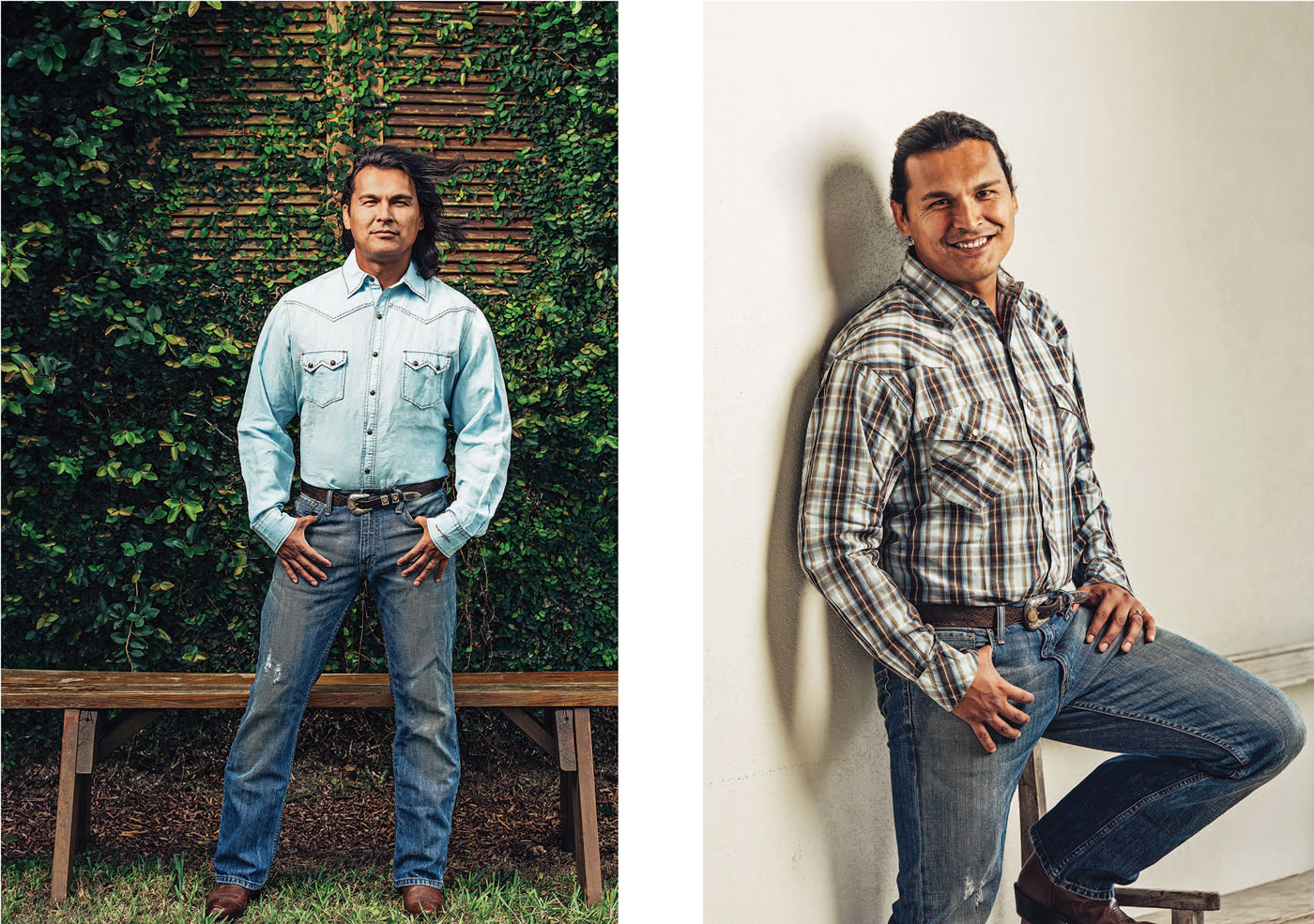

Respected for his body of work, the accomplished actor continues a lifelong mission to raise awareness of the Native experience through art and outreach.

The notion that Adam Beach isn’t yet a household name confounds many — he’s done enough important, impressive film and TV work to earn that status many times over.

The 44-year-old Canadian has racked up dozens of big- and small-screen credits stretching back to the early 1990s. A Saulteaux Anishinaabe from Lake Manitoba First Nation, Beach has shined in everything from historical tearjerkers (Flags of Our Fathers) to goofy comedies (Joe Dirt) to superhero hits (Suicide Squad) to prestige TV dramas (Big Love, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit) in his two-decade-plus career.

But guaranteed top billing and endless fortune aren’t necessarily what drive Beach in his career. The actor, who last appeared on C&I’s cover at age 28 back in 2001, seems to be fueled by a purpose much truer to his identity and his roots.

While his versatility and propensity for risk-taking remain strong suits, Beach will be the first to tell you there’s a certain kind of role he always comes back to — a calling of sorts that keeps him grounded and reverent. He’s proud of his Native heritage and of the history that’s indelibly tied to it. That extends to a trio of new projects coming later this year — buzzed-about movies Hostiles and The Watchman’s Canoe and the small-screen production Monsters of God.

“I recognize who I am through the color of my skin, and want to represent that through my choice of work and characters I play,” Beach told C&I back in 2013.

He has been playing indigenous characters since he was cast in the titular role of 1994’s Squanto: A Warrior’s Tale. His breakthrough part came four years later in Smoke Signals, the film adaptation of author Sherman Alexie’s The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, which won the coveted Audience Award and the Filmmaker’s Trophy in the Dramatic category at the 1998 Sundance Film Festival.

The character that brought the young Beach a new level of critical acclaim was that of Ben Yahzee in John Woo’s 2002 hit Windtalkers, the story of the Navajo code talkers whose use of Native language was indispensable to the United States during World War II. That role had a tremendous impact on Beach, the actor and the budding activist, as he was helping to retell unsung heroes’ stories to a new generation.

“My insight into moviemaking at that time and the film industry in general was to try and understand how large the American Indian perspective was in the world,” Beach tells us. “How far do we look into the life of Native Americans as individuals today?”

An admirer of Beach’s work in his own film and others’, director Woo lauded the actor at the time of Windtalkers’ release for “using modern ways to translate his Native culture.

“The code talkers are the background of the film; the real story is about friendship, and it was really important for all the actors to work together as a team,” Woo told C&I in 2001. “Adam brought that to the film; he’s totally unselfish. He has that kind of spirit.”

“Wow, I like his choice of words,” Beach says when reminded of Woo’s compliment. “I’m very honored to carry my tradition on my sleeve ... as a man and cultural teacher. I want to be an actor whose mission through my film and television work is to preserve our language and culture, and prove we’re not going to disappear.”

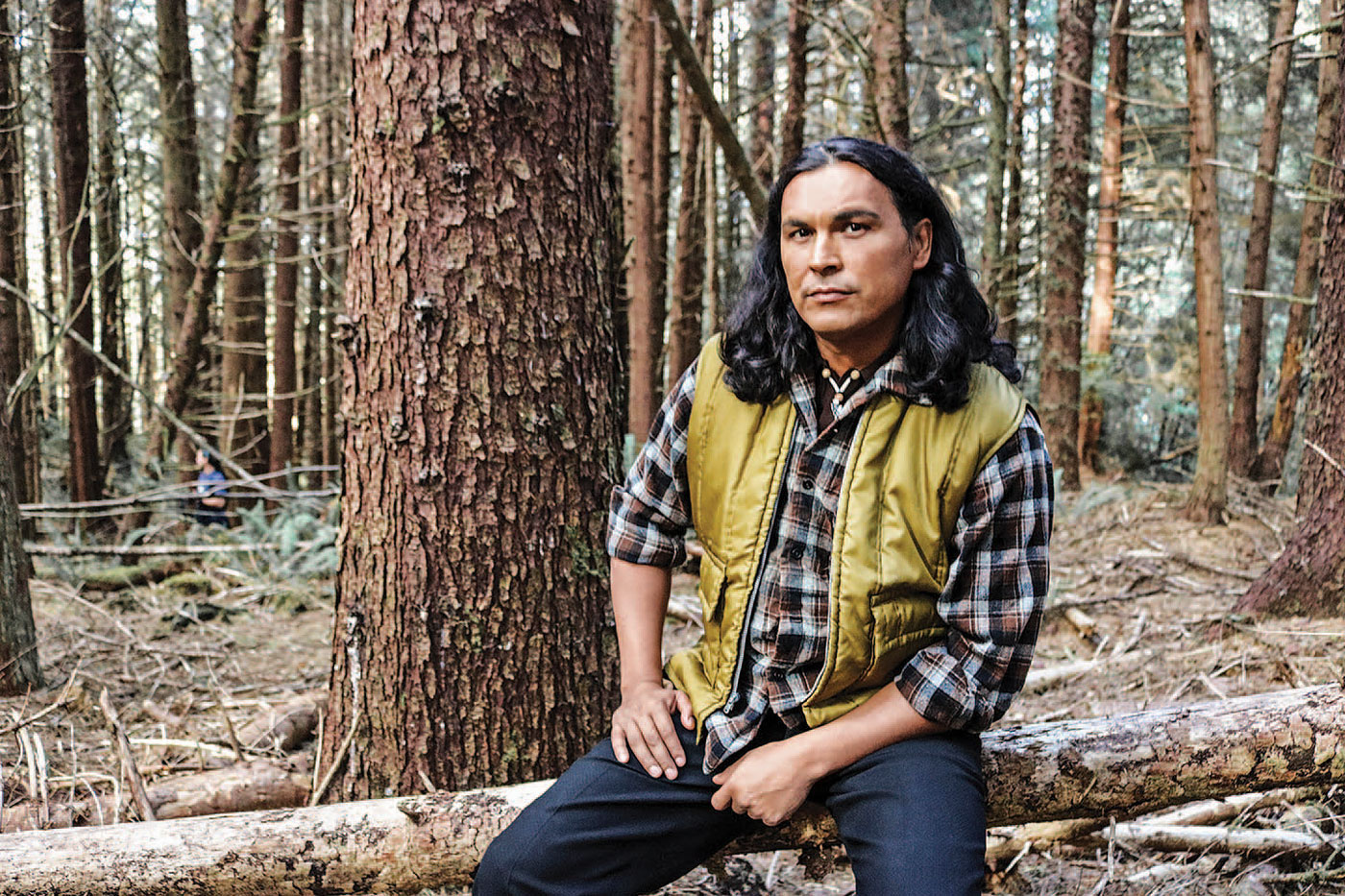

The actor’s dedication to authentic Native characters is as strong as ever in 2017 with three upcoming high-profile projects. He plays a beleaguered Cheyenne in Hostiles, an endangered Comanche in Monsters of God, and a Native American historian and writer living in northern Oregon in The Watchman’s Canoe.

Hostiles (scheduled for release later this year) is the biggest production of his projects on the horizon. Set in 1892, it tells the story of a U.S. Army captain (Oscar winner Christian Bale) who is tasked with escorting a dying Cheyenne elder (Cherokee actor and past C&I cover star Wes Studi) to sacred territory in the north. Capt. Joseph Blocker begrudgingly agrees to escort Yellow Hawk and his family from an isolated Army outpost in New Mexico to tribal lands on the grasslands of Montana.

Beach plays Yellow Hawk’s son, Black Hawk, and he and Studi are initially seen crossing the landscape bound in shackles — until danger strikes, and soldiers and the extended Cheyenne family have to fight together in order to survive.

Beach sees this cinematic journey, directed by Crazy Heart alum Scott Cooper and filmed on location in New Mexico, as a coming together of two peoples “who have to observe and move beyond their one-dimensional look at each other. There is also a strong connection to family, especially between Yellow Hawk and Black Hawk.

“Wes, who plays my chief and father, is the best at what he does, and I bow down to him when we’re working together,” Beach says. “The Cheyenne language ... is how we communicate in the film, with the help of off-screen interpreters.” Beach explains that his character’s name, Black Hawk, has a deep meaning, evoking “energy coming from the black sky above and the blackness of the universe coming to earth to honor me.

“Capt. Blocker, played by the remarkable Christian Bale, allows us to take this journey so that my dying father can be laid to rest in our sacred Montana burial ground. Christian brings such an intensity and commitment to his character — his arc represents the growth in his humanity.”

Studi, a full-blooded Cherokee, is also known for his compelling Native characters in such films as 1993’s Geronimo: An American Legend and 1992’s film version of James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans.

“Adam plays my son [in Hostiles],” Studi tells us in a phone chat, “and we are treated as prisoners of war during the beginning of the film. However, when the Comanche start to track us as they are after our women, guns, and horses, we are set free of our shackles by Blocker to fight side-by-side for one last stand.

“Everything we filmed was on location. We were shooting during the monsoon season, July through September, and there is a no-film-[during]-lightning rule in New Mexico, so we were frequently under a lightning delay. It would rain for days and we were riding horses that were sopping wet with steam coming off their bodies, and actors were on horseback in wet wool period clothing. I felt so sorry for Scott [Cooper], who is a wonderful director, as it was so frustrating to have to wait and wait for the weather to clear. The location became a character in the film — similar to The Revenant — but there was not so much grunting going on.”

Rounding out the impressive cast: Yellow Hawk’s daughter and Black Hawk’s sister Moon Deer is played by Q’orianka Kilcher (The New World). Ben Foster (3:10 to Yuma, Hell or High Water) and Rosamund Pike (Gone Girl) also turn in supporting roles.

A western that Variety.com reports was influenced by such John Ford pictures as The Searchers and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Hostiles was shot on location at the historic Ghost Ranch near Santa Fe. It may ring a bell as the place where legendary resident Georgia O’Keeffe painted some of her most remarkable work.

With Hostiles already in the can, Beach is now working on the production of TNT’s upcoming project Monsters of God, written and directed by veteran auteur Rod Lurie. The story, according to Deadline.com, is set in post-Civil War Texas, in a once peaceful town called Slater. Its villain (played by Justified ’s Garret Dillahunt) has made it his mission to eliminate the Comanche tribe from existence. A cutting-edge writer and director, Lurie rose to prominence at the helm of 2000’s The Contender, starring Joan Allen, as well as the 2001 Robert Redford film The Last Castle.

Dillahunt’s character, Col. “Terrible” Bill Lancaster, is a former Union soldier who has taken charge of the Fort Thayer military base. Beach stars as the young Comanche warrior Sees Two Moons on a quest to avenge his displaced people.

“I play the son of another powerful chief,” Beach says. “The Comanche had such a beautiful way of life back then and never wanted to leave their land. When Lancaster starts to disrespect their way of life and offend their land, the only option is to fight.”

Beach, who stays informed not just on Native issues but on the worldwide political landscape, is quick to point out the parallels in Lurie’s period piece.

“Rod drew into the late 1880s the natural instinct of living in 2017. The story deals with anger and racism and disrespecting different cultures, beliefs, and boundaries,” Beach says.

Monsters looks to be an intense, complex, and addictive experience for the viewer. While it’s officially on the books as a TV movie, some online reports have suggested that the cable network is open to expanding it into a series (UPDATE: Deadline.com reports that the project is no longer at TNT and is now being shopped to other outlets).

Last in Beach’s trio of Native-themed projects is The Watchman’s Canoe, set in 1969. The film’s young protagonist, Jett (Kiri Goodson), is a fair-skinned Native American girl having a hard time fitting in on the reservation. After looking to nature to give her guidance in dealing with being bullied, Jett stumbles upon a kind of coming-of-age journey. Beach plays Nick, a writer living in the Pacific Northwest coastal islands.

“This movie is about listening to your environment to find out who you are,” Beach explains. “The watchman is a spiritual teacher living in northern Oregon who helps to guide Jett on her journey.”

Out of all the characters Beach has taken on of late, that character probably sits the closest to his true nature as an actor and a humanitarian.

Off-camera, Beach has a long history of involvement in suicide prevention and awareness for Canada’s First Nations community. He says he is constantly asking, “Why does this happen?” “Money can help ease the situation, but I think that there is an identity crisis here with our young people on the reservations. They are giving up and taking their own lives, and perhaps this is due to 500 years of abuse and humiliation.”

Beach and his wife, Summer Tiger, who is part Seminole, are currently developing a project called Sacred that deals with this very subject. Tiger, who has a master’s degree in clinical psychology, is writing a script that focuses on something now thought to be a “suicide spirit” roaming the reservations. “This will be a story of both horror and hope,” Tiger says.

As they work on Sacred together, the couple is supporting Native artists in their community by way of the Adam Beach Film Institute, a program for up-and-coming filmmakers based in Beach’s childhood hometown of Winnipeg, Manitoba. The institute, which has its own school with scholarships and classes, has been fully funded for three years by the governmental organization Service Canada.

“The school can house up to 56 Native students over three years,” Beach says, “and the grant allows us to give them a salary and living allowance to pursue their passion. If a student wants to continue in their chosen field, I will do my best to help them get a first job.”

For Beach, his outreach and his own acting work fold naturally into his larger mission — the quest to keep Native history and visibility alive. Over the last 200 years there has been a “deconstruction of the indigenous people by stripping them of their language, culture, beliefs, and values,” he says. “It is so important for the artist to step up and represent us through the arts.”

We’d be hard-pressed to think of a better representative than Beach himself.

Find out more about the mission of the Adam Beach Film Institute at www.adambeachfilminstitute.ca.

From the May/June 2017 issue.