From his youth in small-town Oklahoma to his acting career in Hollywood, full-blooded Cherokee and general Renaissance man Wes Studi has pursued the path of positive change.

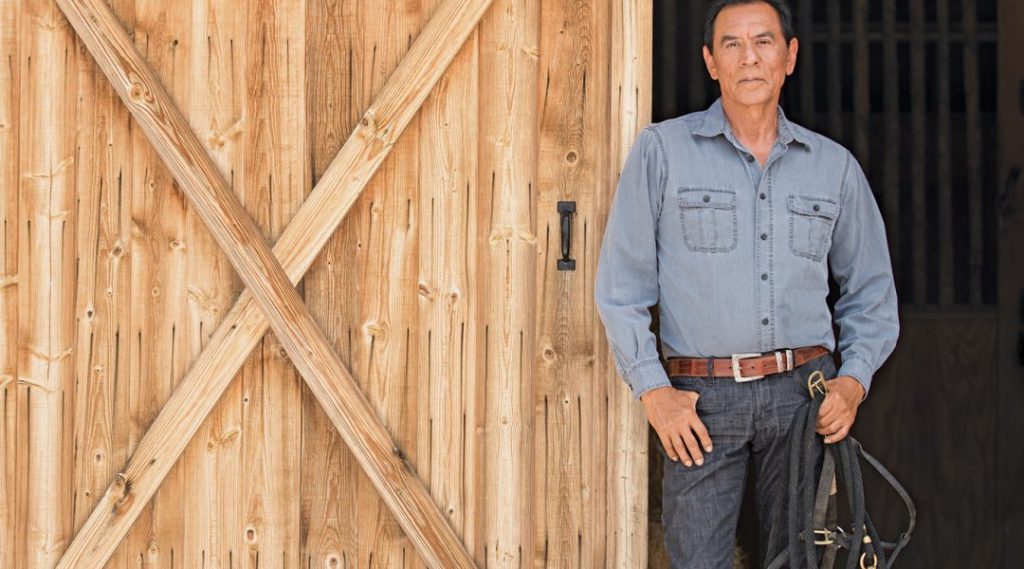

Wes Studi’s behind the wheel of his vintage Cadillac heading down a dirt road en route to the Annandale Tiger Horse Ranch in rural Santa Fe. In the caravan following are the C&I folks who will spend the better part of this enjoyable blue-sky New Mexico day at a photo shoot of the famous Native American actor working with the Tiger Horses he’s been training for seven years.

The early morning call has been kicked off with plenty of coffee at Harry’s Roadhouse. Caffeine onboard and dust settling now that the cars have reached their destination, Studi and the crew are greeted with a lovely view of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and an effusive welcome from the ranch Dalmatian. The man of the hour — dark and handsome, charming and charismatic, his cinematic intensity a bit tempered in person — is ready to get to work. Time to head for the horses.

Horse trainer is just one of the many faces of the surprising Wes Studi. A full-blooded Cherokee, he’s a man of many talents and could have chosen any number of paths in life. He ultimately went with acting, and that road has led to his becoming perhaps the most acclaimed Native American actor working today. As a testament to his work in film, television, and stage reflecting the American West, Studi was inducted into the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum’s Hall of Great Western Performers in 2013, only the second Native American actor — after Jay Silverheels for his work as Tonto in TV’s The Lone Ranger — to be so honored.

The man who would make The Last of the Mohicans’ Magua one of the most memorable characters in cinematic history didn’t initially set out to be an actor. His career path could instead have been horses — he’s had a lifelong love of them.

The eldest son of a ranch hand, Studi, who was born in 1947 (or 1946 — Studi once said in an interview that he wasn’t really sure) in Nofire Hollow, a rural area in northeastern Oklahoma, grew up around horses. His first gig after college was running his own ranch and training horses professionally in Tulsa. So it’s something like coming full circle that on the Santa Fe property he shares with wife Maura Dhu, Studi doesn’t just play horseman — he lives it.

However, the most familiar of his many faces isn’t one of Studi as masterful horseman riding smooth in the saddle across a high-desert field on a gaited horse. It is, of course, the onscreen visage. He’s been Red Cloud, Wovoka, Cochise, and Geronimo in a film career that boasts dozens and dozens of roles and shelves of awards. But movies and TV represent less than half of his 67 years.

Over the course of his multifacted life, Studi has helped start a bilingual Cherokee newspaper. He’s taught his first language, Cherokee, in the Cherokee community. He’s written two children’s books for the Cherokee Bilingual/Cross Cultural Education Center. He’s released a CD with his band, Firecat of Discord. And he’s become a darn good stonecarver. Linguist, activist, artist, musician, horse trainer — call him a polymath or a Renaissance man. Wes Studi’s got all kinds of game — onscreen and off.

Most recently his familiar face has been seen on the small screen in the second season of SundanceTV’s The Red Road as Levi Gall, the slick and self-serving chief of a wealthy Connecticut reservation at odds with his family and community over the building of a casino on Native land. Studi’s most widely recognizable incarnation, though, would have to be one of his earliest: sporting a mean mohawk as the fierce heart-extracting Huron warrior Magua in The Last of the Mohicans. That star-making 1992 portrayal made Studi’s face unforgettable the world over and made his the iconic interpretation of the James Fenimore Cooper character. The following year, he played the title character in Geronimo: An American Legend alongside Gene Hackman and Robert Duvall, a performance that earned him a Western Heritage Award.

Studi’s been playing Indian leaders, both historical and fictitious, for more than 20 years now. And the roles keep coming. In 2009 he costarred in James Cameron’s science fiction epic Avatar as Eytukan, the chief who represents the values and strength of the Na’vi, the tribe of sentient extraterrestrial blue humanoids who resist human invaders threatening to destroy their way of life. In 2011 and 2012, he played Chief Many Horses for two seasons on AMC’s 1860s transcontinental railroad western Hell on Wheels. And last year, Studi teamed up with his Seraphim Falls costar Liam Neeson to play Cochise in Seth MacFarlane’s western farce A Million Ways to Die in the West.

In his most recent outing in SundanceTV’s The Red Road, which revolves around the strained relationship between a New Jersey town and the Lenape Indians who live nearby, Studi tackles Native American modernity — casinos, identity issues, politics. How did that stack up against the historically based Chief Many Horses? “I think it’s just as challenging in the modern day as it was then,” Studi told SundanceTV. “While actual physical lives were a great matter back in the days of the Hell on Wheels chief that I played, now it’s more like financial lives — reputations and social status with what Chief Levi Gall purports to do. I don’t think the stakes are any different, just perhaps the measure of them is different.”

Studi may see a little of his old activist self in the character. A veteran of the American Indian Movement, the actor was arrested at the Wounded Knee occupation in 1973. He similarly sees Gall, a member of one of the Algonquin tribes, as an AIM veteran who has taken another path later in life.

“He was an activist from those days and, like many who were involved then, has moved into prominence and developed many business interests along the East Coast, including several gaming casinos,” Studi says. “He’s a man trying to catch up with his old self and perhaps start to do right by family members he has wronged in the past. He has a son with a woman from the Ramapo Mountains and is now at an age where he wants to mend the broken relationship with Junior, a very conflicted young man who never had any kind of real relationship with his father. Once we reconnect, I try to make him understand why my character made the decisions he did.”

The last episode of the second season comes to a shocking and bloody conclusion. Unfortunately, SundanceTV canceled the show, leaving fans in the lurch. But before being violently dispatched to his uncertain fate, Gall makes a comment that seems to carry a hint of Studi autobiography: “You don’t get to choose who you are — it’s in your blood.”

It seems that it was in Studi’s blood to end up in Hollywood, especially since he took the long way around — by way of Vietnam. After graduating from Chilocco Indian boarding school in northern Oklahoma, Studi joined the Army. While stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia, with only 12 months of his six-year service left, he volunteered for the front after hearing the stories of soldiers returning from combat. He served one tour in South Vietnam with the 9th Infantry Division, at one point being pinned down with his company in the Mekong Delta and nearly being killed by friendly fire. The combat experience would become first-hand fodder for his future warring characters and would especially inform his portrayal of Magua.

After an honorable discharge, Studi returned to Oklahoma and channeled his energy into Native American politics. He joined AIM; marched on Washington, D.C., in 1972 in the Trail of Broken Treaties; and a year later participated in the occupation of Wounded Knee in South Dakota.

“The movement made you make a choice,” Studi says. “At that time in history you were either in or out.” Although he was all in, that particular path didn’t prove his calling. After his arrest at Wounded Knee, Studi decided to channel his activism back home, in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

After attending Northeastern State University in Tahlequah, Studi helped start the Cherokee Phoenix, a bilingual newspaper that is still being published. He also put his linguistic skills to use teaching his native tongue in the Cherokee community.

But although language had become his avocation, acting would become his passion. Studi started performing at the American Indian Theatre Company of Oklahoma in Tulsa, costarring in Black Elk Speaks. By 1987, he had moved to Los Angeles, where he quickly landed a small role as Buff in the Cheyenne rez road trip story Powwow Highway (1989), followed by memorable supporting roles as “the toughest Pawnee,” a scalping and torturing nameless killer in Dances With Wolves (1990), and as “Indian in the desert” in the rock biopic The Doors (1991). A year later he was riveting and terrifying as the vengeful Magua in The Last of the Mohicans.

Lanky and muscular in a leather loincloth, Studi didn’t just look the part — he knew how to draw on his own varied and profound life experience to tell the larger story. “Knowing history and the betrayal experienced by the Indians, a lot of the anger expressed by Magua was influenced by the bad blood, so to speak, between the Indians, settlers, and the Europeans during the 1700s,” Studi says. That interpretation of the iconic villain of James Fenimore Cooper’s historical novel transformed Magua into the almost heroic figure of Michael Mann’s Mohicans and launched Studi’s career.

In another opportunity to portray Native history, Studi was cast the following year in the iconic title role of Geronimo: An American Legend. “Geronimo was a symbol for many people in many different ways,” he says. “[He] was a man who actually influenced history.”

Studi takes the responsibility of portraying historical figures seriously. “Fleshing out a historical figure depends on how much research you do and how, as an actor, you put it into effect,” he says. “Ultimately you have your own interpretation of who this person really was, and you have to create the actions and reactions that the character would most likely do in a particular situation.”

Given the choice, however, Studi says he would rather play fictional characters. You can tell a lot of truth with fiction — or science fiction for that matter. Take Eytukan, for example, the tribal leader Studi portrayed in Avatar. Though the character is fictitious, Eytukan carried the weight of his people. For that reason, Studi likens him to Geronimo: “The outside world may have seen these men as leaders, but they were more like seers or prophets who fell to the role of war chief due to their circumstances,” Studi says. “Eytukan saw that there was going to be conflict with the humans and kept a wary eye on the situation until his death.”

The decade following Geronimo saw Studi branching out into more modern roles, starring as the eye-patch wearing black-market arms dealer Sagat in the video game turned Jean-Claude Van Damme action film Street Fighter, and working again with The Last of the Mohicans director Michael Mann as Al Pacino’s partner, Detective Casals, in the 1995 crime thriller Heat.

Returning to historical portrayals, he played Oglala Lakota war leader Chief Red Cloud in the television movie Crazy Horse. Then in 2002 he began a three-year collaboration with bestselling detective-novel writer Tony Hillerman on film adaptations of his Navajo Tribal Police mysteries, starring as the “extremely gung-ho” Navajo Lt. Joe Leaphorn in Skinwalkers, Coyote Waits, and A Thief of Time, all produced for PBS by Robert Redford.

“To prepare for the [Leaphorn] role I looked back at some of my relatives and other people I knew from high school who went on to become police officers, deciding to become a part of society, and these people took a great reward in what a job like that had to offer,” Studi says. A similar sense of care and responsibility accompanied his preparation for roles as other unique Native characters as disparate as Cherokee bounty hunter Sam, who is striving for acceptance in a white world while on a mission to return a runaway teen to an early 1900s boarding school, in the Studi-produced The Only Good Indian; as Opechancanough, tribal chief of the Powhatan Confederacy, in Terrence Malick’s 2005 romantic historical drama The New World; and as Wovoka (alongside First Nations actor Adam Beach), the Northern Paiute religious leader who founded the Ghost Dance movement, in Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.

Even with so much acclaim for these and many other movie roles, Studi continues to walk the way of the activist and educator. Sometimes a project engages both his love of language and love of film. Little-known fact: On Avatar, he served as a language consultant. “I was one of the actors working on the film who had studied phonetic languages, so I worked with the linguist making up words for the Na’vi language. I was basically part of the team and helped the actors learn Na’vi. It was quite an experience,” Studi recalls. “A person who is bilingual has an advantage — we’re not quite so self-conscious about sounding wrong and about not being able initially to make certain sounds for a particular made-up language.”

More important, he’s using those skills with real languages in the real world. He remains a passionate advocate for and has taken a national leadership role in promoting and preserving indigenous languages as a spokesperson and honorary board member for the Santa Fe-based Indigenous Language Institute. A man who says he likes to be busy, he’s also active in mentoring the next generation of filmmakers and performers.

That’s where Wes Studi’s path has taken him thus far — up to this moment, in this field, on this horse ranch. If your own path should go beyond the streaming queue that could keep you entertained with his films for a long time and lead you to the land of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, you might find the man training Tiger Horses out at the ranch. Or, if you’re in New Mexico at the right time, you might catch him in another of his favorite roles, fronting Firecat of Discord with wife Maura singing their mostly original songs. The band — which released a self-titled CD back in 1998 and toured the United States in 2000 — isn’t very active anymore, but Studi hasn’t hung up his bass just yet. Every other June the Firecats get together to entertain at the Toadlena Trading Post in Newcomb, New Mexico, to celebrate the opening of the current exhibit.

If you’re really lucky and Studi gets his bucket wish, you might catch him starring someday in a spaghetti western. With the photo shoot wrapping, the sun sinking behind the Sangre de Cristos, and Studi and the Tiger Horses silhouetted in a cinematic fading light, you can cue the Ennio Morricone soundtrack in your mind and see how it just might happen.

From the August/September 2015 issue.