The renowned — and controversial — Native American writer talks about portrayal of Indians in cinema, sports mascots, and his new children’s book, Thunder Boy Jr.

Author, poet, screenwriter, and stage comedian Sherman Alexie (Spokane/Coeur d’Alene) has found a new format in which to flex his creative muscles: children’s books.

Yes, the writer of a novel that’s been banned from school libraries has a children’s book on his résumé. For Alexie, the picture-book, released in May, was one of the hardest things he’s ever had to write.

“It took me years to find the right story,” he says. “And then it took me a couple of more years to write the book. You have to make every word count. I’m a poet, so I thought it would be easier because of that, but it wasn’t. This is a very specialized kind of poetry. And I’m very respectful of picture-book writers. It’s a tough gig.”

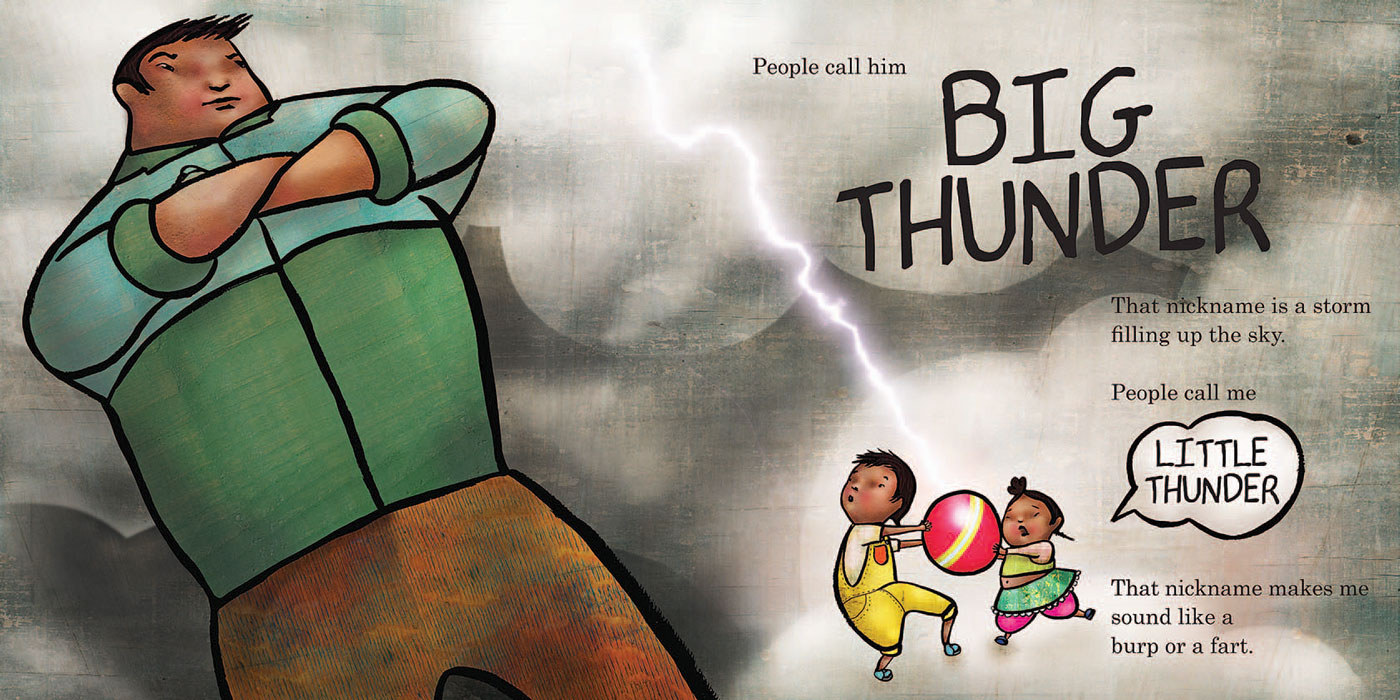

With the help of illustrator Yuyi Morales, Thunder Boy Jr. (Little, Brown and Company, 2016) neatly tells the story of a young Native boy who loves his father but wants his own identity. It was a change for Alexie, whose work typically gives audiences an inside look at the pains and humor that mark the contemporary Native American world. Thunder Boy Jr. doesn’t have the biting wit or social commentary that rages in most of Alexie’s works, but it helps him wag a finger at parents who, for vanity’s sake, name their children after themselves.

The book might as well be the story of a young Alexie, who spent his childhood on the Spokane Indian Reservation in Washington. Like the title character, he was named after his father and yearned to make a name for himself. Inspiration for the book came to him 13 years ago at his dad’s funeral, when he saw his own name on his father’s grave marker.

Alexie’s new book reflects a gentler side of the Seattle-based author as he enters his 50s. His signature, award-winning novel, 2007’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, sold a million-plus copies and made The New York Times’ bestseller list. It also regularly lands in another list: the American Library Association’s annual roundup of challenged titles. Diary has been banned from the shelves of some libraries and school districts because of its content.

Before that, Alexie repurposed his 1993 short story collection, The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven, into a screenplay for the first mass-distributed all-Native movie, 1998’s Smoke Signals, which collected awards at film festivals, including the Filmmaker’s Trophy at Sundance. Alexie is also a vocal supporter of independent bookstores. He was behind Indies First, a four-year-old national campaign of activities and events in support of independent bookstores.

At personal appearances, Alexie talks with young adults and researches the kinds of literature they crave. The bans? He brushes them off.

“The bans create more interest and more love for my book,” he says. “It always has.”

Alexie talks about his book, the mascot debate, and Natives in cinema in an interview with C&I.

Cowboys & Indians: Regarding Thunder Boy Jr., what was your experience in working with Yuyi Morales, the book’s Mexico-based illustrator, on a children’s book?

Sherman Alexie: [She] worked on it independently. She would send things in and I would approve. I’d picked her based on other books she’d done and how amazing she is. I trusted her. And she did amazing work.

C&I: Are more picture books in your future?

Alexie: This one tells the story of an Indian boy. I think my next one will tell the story of an Indian girl. I put a Native boy on an adventure, and now I’ll put a Native girl on an adventure.

C&I: What’s the secret to sustaining creativity now that your environment has changed?

Alexie: I’ve got kids, so I do a lot of driving to school and to their various events. Plenty of my hours are spent taking care of my sons. I’m good at writing in whatever situation I happen to be in. I’ve written a lot of poems sitting outside school, waiting in my car. I could probably write a book called Poetry From the Minivan.

C&I: You’ve been an outspoken critic of sports mascot imagery. Where do you stand on the Washington Redskins debate?

Alexie: It’s utterly racist. There’s no debate about it. Period. There’s no negotiation. No room for compromise. A sports mascot made on a conquered people is utterly racist. The first thing I always do when I’m addressing people who are pro-mascot is I ask them to call me a redskin. “No. Stand up right there and call me a redskin. Right now. Call me a redskin.” Nobody ever has. The way I know redskins is a racist term is because nobody has ever called me that in a positive manner.

C&I: Given the exposure of Natives and First Nations people in The Revenant, has the entertainment industry turned the corner on portraying Natives?

Alexie: It showed a positive character in the Old West. That’s not really making strides. I think the revolutionary moments are when, for instance, Graham Green played a cop in Die Hard [With a Vengeance]. Or when Wes Studi played a cop in Heat. When those sort of opportunities happen for a Native American actor to portray a contemporary citizen, that’s what I think is revolutionary.

C&I: Are you saying that Native American cinema in the mainstream hasn’t changed very much at all?

Alexie: Smoke Signals remains the only Native-directed and -written film that’s ever had a major distribution deal, that’s ever played internationally, or in more than two theaters at once. And that movie came out 18 years ago. There hasn’t been another big one like that since. I still think we have not had the opportunity to have a really big mainstream film.

C&I: What’s it going to take for Native cinema to move the needle?

Alexie: We really need a Native actor to become a big star. And Adam Beach was almost there, and it just didn’t quite happen. There was talk of him getting an Oscar nomination for Flags of Our Fathers. I think if he’d gotten that nomination, perhaps he could’ve become bigger and been the kind of movie star that people would green-light movies based on him being in it. But we need a Native actor to become a star, and for that Native actor to still want to play Native American roles. One of the difficulties of being a Native actor in Hollywood is you take the role, and you end up putting on the loincloth. ... If you want to keep working, you’re going to have to put on the loincloth. That’s a tough decision for a Native actor. And, it’s certainly one of the reasons why I don’t work there very much. I knew I’d have to eventually write one with Indians wearing loincloths.

C&I: Explain why the Indies First campaign is so important to the literary world.

Alexie: ... [W]riters go into bookstores on Small Business Saturday, the Saturday after Thanksgiving, and become booksellers, and really support the stores by being there and promoting their books and promoting other people’s books and promoting the store itself. It’s a celebration of independent businesses and small independent voices. It’s been a huge hit. Every year, over a thousand writers participate, so it’s been wonderful.

From the October 2016 issue.