One of the most legendary and daring stagecoach drivers in America held on to a lifelong secret — and quietly made history in the process.

It's 1851 in California, and the gold rush rages.

The country is on edge — expanding, dividing, and teetering between ambition and chaos. The recent war with Mexico has added vast new territories, but the Compromise of 1850 struggles to hold together this increasingly fragile Union. All the while, railroads are creeping west and Manifest Destiny drives crowds chasing fortune, land, and power.

It's a simpler story here in Northern California: Gold is calling.

But California Dreamin’ be damned — this ain’t that place. The sovereign siren call has drawn half a million rapscallions, ne’er-do-wells, schemers, dreamers, and speculators, flooding the brand-new state, grunting through mud, muck, and murder, hunting their way toward wealth, wisdom, and wondrous whereabouts.

At the moment, this land is a beautiful nightmare — a wild, untamed expanse where rugged trails twist through moss-wrapped redwoods, golden foothills stretch beneath an endless sky, and the Sierra Nevada looms, a jagged fortress casting long shadows over bustling mining towns.

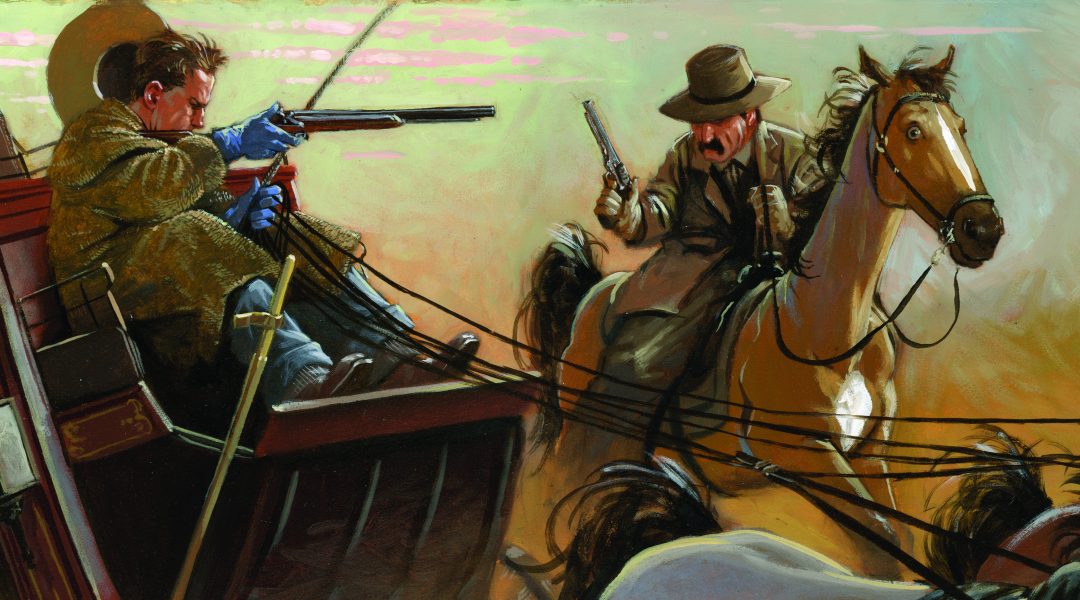

For those ready to make their scratch, getting there requires tenacity. Better be ready to risk their life on dusty, perilous paths, trusting wondrous whips (stagecoach drivers) to navigate the treacherous terrain. These whips are rare and revered — renowned as the celebrity daredevils.

Maybe the most legendary of them all? Charley Parkhurst.

A scrawny, one-eyed, tobacco-spitting, whiskey-sipping, whip-cracking, thrill-seeking pathfinder who spent two decades commandeering coaches, porting packages, and ferrying people across the state — grappling with hazards and holdups to become perhaps the fastest, most reliable driver of the era. That prowess was so legendary that — even if it were only for the few stories of haranguing hijackers, whipping wisecrackers, handling hair-pin turns over cliff tops, and surviving frigid freezes — the name Charley Parkhurst would be etched among the West’s greatest.

Lucky for us, there’s even more to this story.

What's In A Name?

Parkhurst likely arrived in California around 1850, drawn by opportunity and refuge. The details of Parkhurst’s early life? Complicated. Stories contradict, but most agree on a few documented facts.

- Date of Birth: Jan. 17, 1812

- Place of Birth: Lebanon, N.H.

- Birth Name: Charlotte Darkey Parkhurst

That’s right; Charley was assigned female at birth and spent the majority of life carefully concealing it for unknown reasons. In fact, the only reason we know this now is that when Parkhurst died in 1879 near Watsonville, Calif., after a long battle of cancer of the tongue, a doctor discovered the legendary stagecoach driver was biologically a woman.

The concept and execution of concealing this fact was, at the very least, uncommon in the era. No definitions around gender identities or spectrums existed to convey or label how Parkhurst presented. All that matters: Parkhurst lived a fairly public life and was commonly perceived for decades as a man.

Living as a man didn’t just demand physical toughness — it also required an extraordinary degree of social awareness. Charley likely had to navigate every interaction carefully to avoid suspicion. Yet, by all accounts, Parkhurst was well-liked — even beloved — by peers. Colleagues described a tough but fair-minded type, with a dry wit that earned respect among the rough-and-tumble men of the West.

That ability to maintain friendships while guarding a deep secret speaks to intelligence and adaptability. In a world where women were confined to domestic roles, Parkhurst not only survived but thrived, blending seamlessly into male-dominated spaces.

Story Sweeps The Nation

After death, the discovery became a local sensation as reporters coast to coast tried to piece together the story of Parkhurst’s life. The New York Times (Jan. 9, 1880): “Last Sunday, in a little cabin on the Moss Ranch, Charley Parkhurst, the famous coachman, the fearless fighter, the industrious farmer and expert woodman, died of cancer on his tongue... Then, when the hands of the kind friends who had ministered to his dying wants came to lay out the dead body, a discovery was made that was literally astounding. Charley Parkhurst was a woman.”

The San Francisco Call: “The case of Charley Parkhurst may fairly claim to rank as by all odds the most astonishing of them all.”

The Providence Journal: “While in the poorhouse, he discovered that boys have a great advantage over girls in the battle of life, and he desired to become a boy.”

Back To Beginnings

Parkhurst’s early life? Bleak. It was, in all likelihood, a miserable, misspent youth. In small-town New Hampshire, Parkhurst was abandoned at a young age, orphaned, and left to endure a harsh childhood in an institution that offered little more than the bare means to survive.

In the early 19th Century, institutions for abandoned children were often overcrowded, underfunded, and bleak. Children were expected to work long hours in exchange for meager meals and a roof over their heads. It was a life of survival, not nurturing, and Parkhurst likely learned early that self-reliance was the best chance at freedom.

Sometime as a teen, Parkhurst fled the institution, dressed in boys’ clothing, and disappeared in an act of reinvention more than disguise. This was, likely, a declaration of independence.

By becoming “Charley,” Parkhurst gained access to opportunities that would have been unthinkable for a woman. In a world that often confined women to narrow roles, Charley had defied every convention, thriving in a life that demanded courage, skill, and grit. The story challenges an outdated understanding of identity, gender, and the limits placed on individuals by society.

After fleeing the orphanage, Parkhurst spent years working farms, learning how to ride and “drive” horses, and — somewhere along the way — met James E. Birch.

Life In The West

Who’s Birch? He became the biggest stagecoach entrepreneur, who would go on to found both the California Stage Company (the largest stage line in California in the 1850s) and, later, the San Antonio-San Diego Mail Line, America’s first transcontinental mail route.

By 1850, Parkhurst had moved to California and was working under Birch’s tutelage, proving to be no ordinary stagecoach driver — earning a reputation among the greats of the road: “Foss, Hank Monk, and George Gordon.”

Parkhurst’s routes stretched across the rough-and-tumble landscapes of Northern California, from Stockton to Mariposa, the dusty paths linking San Jose to Oakland, and the winding trails from San Juan to Santa Cruz. Driving a stagecoach wasn’t just about speed — it was about survival.

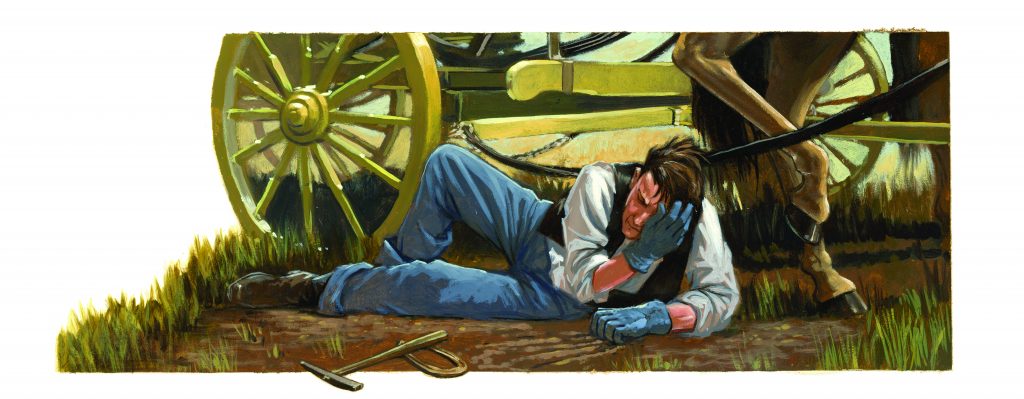

Whips like Charley lived hard, slept cold, and aged fast, trading comfort for callouses and coin. It wasn’t the gunfights or the gulches that wore a driver down — it was the miles.

Parkhurst hauled passengers and mail across treacherous terrain, where bandits lurked in the shadows, storms turned roads to rivers, and sheer cliffs dared a single misstep. It was a time when danger wasn’t the exception — it was the rule.

But even the fastest whip in the West couldn’t outrun progress.

As the railroads crept in, carving new paths, stagecoaches became a relic of the past. Parkhurst saw the writing on the wall and left the driver’s bench behind, settling in Watsonville to farm, cut timber, and raise chickens in Aptos through the winters.

In later years, rheumatism set in, making life slower, harder. Parkhurst’s final days were spent in a small cabin near Watsonville. On Dec. 28, 1879, Parkhurst took his last breath, claimed not by the perils of the trail, but by tongue cancer — one final twist in the life of a legend.

Today, Charley Parkhurst’s life stands as a symbol of resilience, ingenuity, and the power of reinvention. The legacy has been embraced by historians and activists alike, celebrated as both a pioneering woman and a figure who transcends traditional gender roles.

Charley’s life reminds us that history is rarely as simple as it seems. Beneath the surface of the Wild West’s rough-and-tumble lore lies a story of courage, individuality, and quiet rebellion. Parkhurst didn’t just survive — it was thriving, and in doing so, became a legend.

If the West was a land of reinvention, then Parkhurst was its epitome: a figure who refused to be confined by the limits of her time and instead carved out a life that remains as inspiring today as it was daring then.

The Vote That History Never Saw Coming

Living as “Charley” wasn’t just about survival—it was about freedom. As a man, Parkhurst could own land, chase a career that “Charlotte” never could, and carve out a life on his terms. Another right Charley seized? The vote.

In 1868, Charley may have done the unthinkable — cast a ballot in a presidential election. Nearly half a century before women in the U.S. had the right to vote, Charley walked in, disguised as a man, and made history. No one batted an eye. No one challenged the vote. That moment made Parkhurst one of the first women to ever cast a ballot in America.

Back then, voting was a privilege locked behind the doors of manhood. But Charley kicked the damn door down. It wasn’t a speech, a protest, or a revolution. It was a single act of quiet defiance. One vote. One person pushing against the tide of a world that said, You don’t belong here.

We’ll never know what Charley was thinking at that moment. But what’s for sure: history remembers the bold.

Illustrations by Adam Gustavson.

From our October 2025 issue.