Cowboys & Indians speaks with author and historian Margot Mifflin about famous frontier captive Olive Oatman.

Women’s history fascinates Margot Mifflin, as you can tell from her body of work. An author and journalist, she pioneered the study of women’s tattoo history with her 1997 book, Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo and looked at another aspect of womanhood with the first cultural history of the Miss America Pageant, Looking for Miss America: A Pageant’s 100-Year Quest to Define Womanhood. Working and writing out of her home in New York’s lower Hudson Valley — when she’s not teaching in the English department at Lehman College of the City University of New York — she’s presently immersed in a narrative history of the radical Quaker women whose work led to abolition and women’s suffrage.

It was while Mifflin was doing lectures on Bodies of Subversion at colleges and universities that a graduate student at the University of Nebraska approached her and asked if she knew about Olive Oatman. “I was fascinated by what the student told me and came home to discover my little local library had a book that included Oatman’s photo,” Mifflin says. “But I couldn’t find much more about her in print. I researched her story and included it in a second edition of Bodies of Subversion, but it was so hard to fit her whole story into a few pages that I went on to write her biography.”

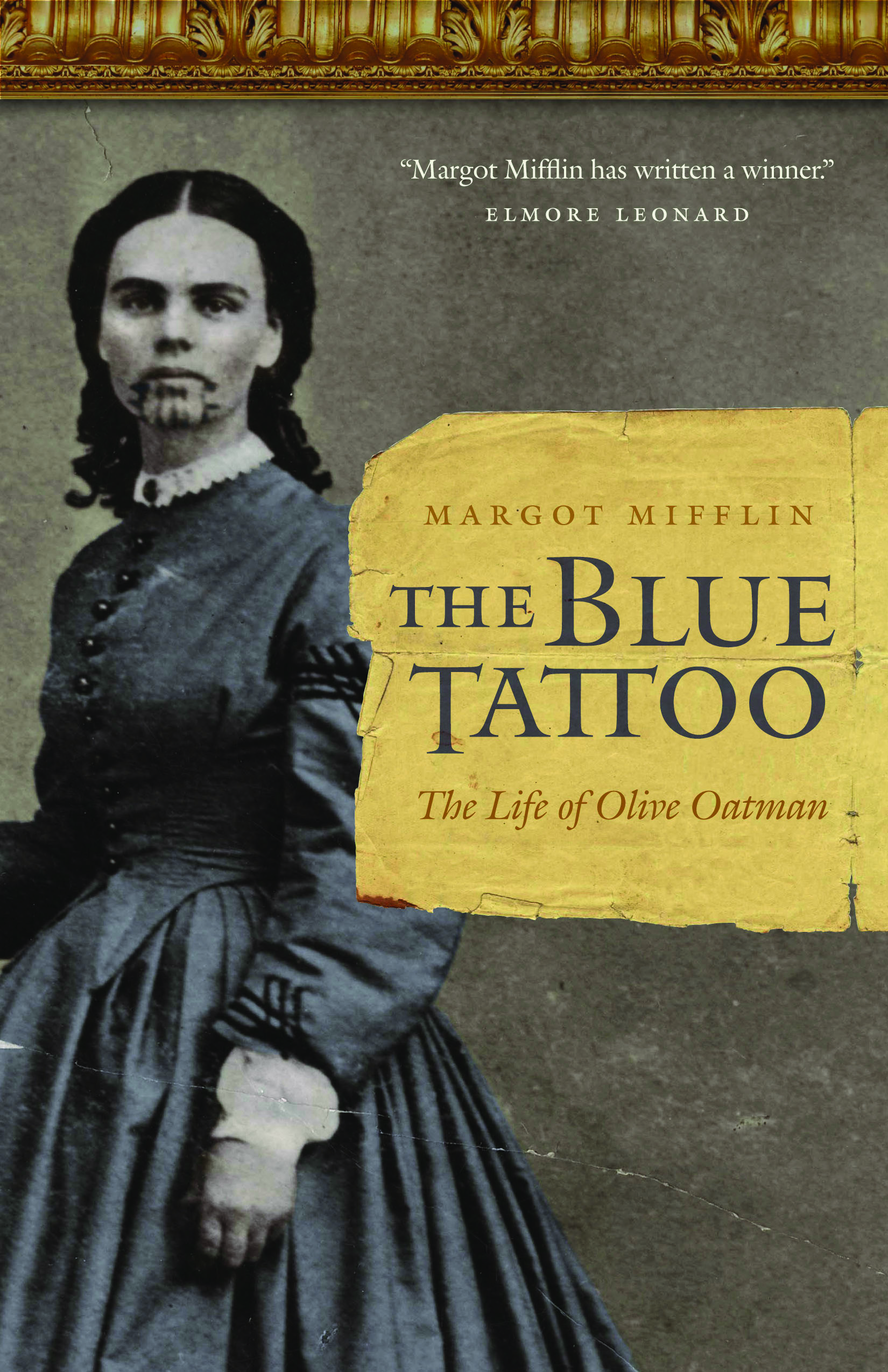

Our current conversation with Mifflin reaches back to that 2009 biography, The Blue Tattoo: The Life of Olive Oatman, which tells the story of the first tattooed American white woman, who was taken captive in a massacre, raised by Mohave Indians who adopted her, and eventually ransomed back to White society. Mifflin’s account delves into not just Olive’s story but also the history of American westward expansion, the Mohave tribe, tattooing in America, and captivity literature in the 1800s. “The book has been optioned,” Mifflin says, “so it’s possible her story will become a TV series.”

We talked with Mifflin about all of the above and why she thinks there’s a resurgence of interest in Oatman.

Cowboys & Indians: For people who might not be familiar, could you briefly tell us about the Oatman Massacre and what happened to young Olive Oatman in the immediate aftermath?

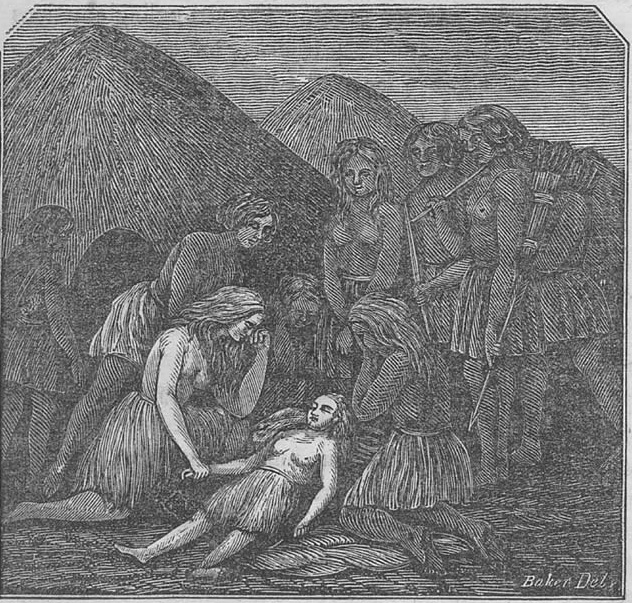

Margot Mifflin: In 1851, Oatman was 13, traveling west to- ward California with her Mormon family when her family was killed by Yavapai Indians. What has come to be known as the Oatman Massacre occurred on the banks of the Gila River, 84 miles east of modern-day Yuma, Arizona. The seven Oatman children ranged in age from 1 to 17 years old.

Olive and her younger sister Mary Ann were taken as captives for a year before being traded to the Mohave, who tattooed her chin and raised her as their own. When she was 19, she was ransomed, by the U.S. military, back to White society, where she became a celebrity. Her story was picked up and published in what became a bestselling book written by a Methodist minister named Royal B. Stratton, who cast her as a victim to “savage Indians,” something she went along with in order to save face in the White world. It would have been unacceptable for her to say she had become acculturated in a society deemed uncivilized in the White world.

C&I: How is her family’s story also the story of westward expansion? What were some of the larger issues of the day?

Mifflin: She was taken at a pivotal period in American history. This happened in the Southwest a few years after the end of the Mexican American War. The 1848 treaty that ended the war, The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, yielded 50 percent of Mexico to the U.S. and expanded the size of the U.S. by 66 percent, mainly adding the territory from Texas to California.

The term manifest destiny had been coined in 1848 to mean going west and taking land White Americans believed was theirs. But, of course, it was already inhabited by Indigenous peoples. Oatman was with the Mohave spanning a period (1851– 1856) when they had had almost no contact with Whites (and certainly no sustained contact) to a time when the first major exploration party came through in 1854. This was the beginning of their decline. Other Whites followed, and within a decade the Mohaves were being pushed off their land and onto reservations, where they’ve been struggling economically ever since. Because they had no written language, Oatman’s impressions of them are an important historical snapshot of how they lived during the last period of their sovereignty.

C&I: How did you go about your research, which must have been extensive, and what were some surprises?

Mifflin: I did research in libraries in California, Illinois, Arizona, and New York, and I visited the Mohave Cultural Center in Needles, California, to interview two elders, Llewellyn and Betty Barrackman, shortly before they died. Mr. Barrackman was the chairperson of the tribe and its unofficial historian — as I understand it, their last. The information they gave me was critical to the evolution of my theory that Oatman didn’t want to leave the Mohave when she was ransomed in 1856, as well as the debunking of the rumor that she had a Mohave husband and children — something that would have been remembered. Mrs. Barrackman also clarified the surprising meaning of the word Spantsa, Olive’s Mohave nickname, which roughly translates as “rotten vagina” or “sore vagina,” suggesting she was very sexually active. Olive almost certainly didn’t marry a Mohave or bear his children. A half-century after her ransom, when the anthropologist A.L. Kroeber interviewed a Mohave named Musk Melon who had known Olive well, he said nothing about her having been married. She did marry after her ransom, and she and her New York-born husband, John Fairchild, adopted a daughter.

C&I: Why did Native Americans attack the family but leave Olive and her sister alive?

Mifflin: Most likely because they were old enough to do work within the tribe and young enough to be assimilated.

C&I: What happened to the girls in captivity?

Mifflin: They were treated as slaves by the Yavapais, in what became Arizona, and traded to the Mohave a year later, when they came on their annual trading run, saw the girls, felt sorry for them, took them home, adopted them, and raised them as their own. Olive bonded with her Mohave sister and mother.

Her mother, Aespeneo, cried all night when Mary Ann died and subsequently saved Olive’s life during the famine that killed Mary Ann.

C&I: What did you come to understand about the Mohave?

Mifflin: They were incredibly funny, social, adventurous, and athletic people. They practiced serial monogamy and raised their children communally. They were great runners and swimmers who spent a lot of time in the Colorado River. I had no idea what a rich culture they had, how isolated they were in the mid-19th century when Oatman joined them (compared to other California tribes), how high-profile they became soon after Oatman left them (not because of her, but because of subsequent White incursions into their valley), and then how quickly they were pushed off their land and utterly forgotten. They were once the largest tribe in California.

A Mohave I met there emailed me after the book came out to tell me she wanted to get a copy for her son in prison so he could know “what we used to be.”

C&I: Olive’s 15-year-old brother, Lorenzo, was left for dead but survived and tried to get help. What happened in his life as he tried for years to search for his sisters?

Mifflin: For most of that time he didn’t even know they’d survived, and he was trying to make a living through various unskilled jobs as a traumatized orphan who was barely literate. When he learned there was a rumor that Olive had survived, he saved money to go searching for her.

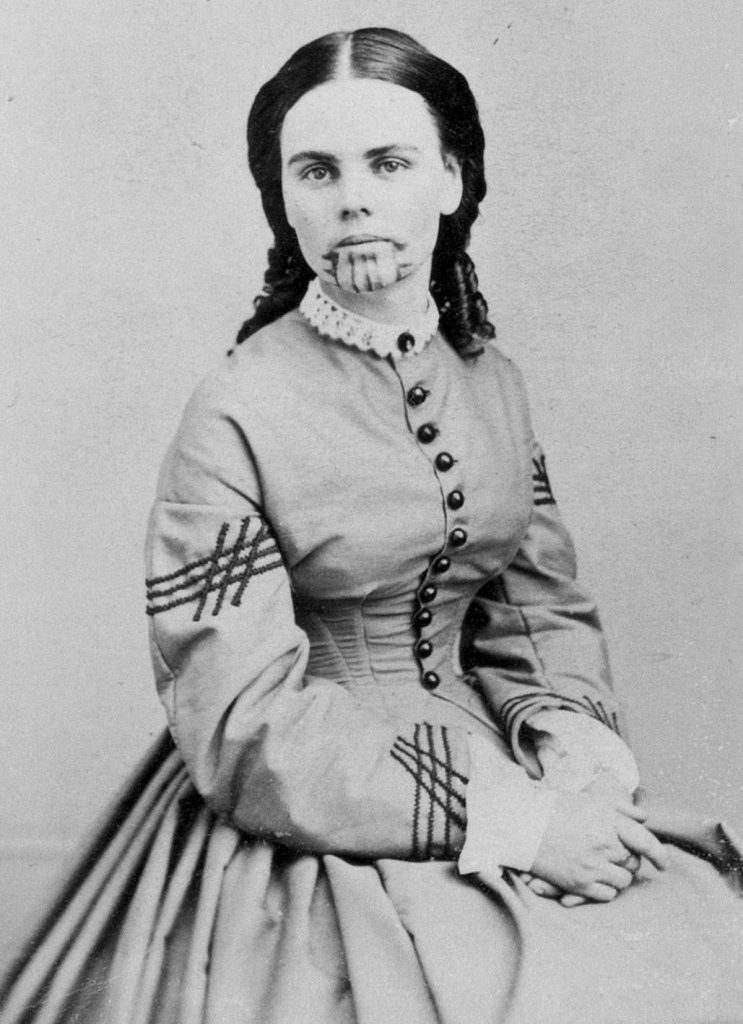

C&I: Tell us about the blue tattoo that was made on Olive’s chin and by which she will forever be identified and recognized.

Mifflin: The book argues that she crossed over and became a Mohave, and that’s largely because of the tattoo. The Mohave gave her a traditional tribal tattoo just like the ones they wore (variants of which are common to other California tribes), which were intended to help them into heaven and make them recognizable to dead ancestors who might not have met them in person. The clean lines of the tattoo indicate she didn’t struggle against it and that she cared for it while it was healing. And though it was historically interpreted as the mark of a slave, this wasn’t true. In fact, Oatman saw some Mohave war captives during the time she was with them, and they weren’t tattooed.

C&I: You titled your book about Olive The Blue Tattoo. You have studied tattooing a great deal, especially as it pertains to women. In Olive’s case, what is the deeper significance of the tattoo and how did it affect her?

Mifflin: It’s a mark of belonging, but for an outsider wearing it, its meaning was unique for Oatman. It indicated her divided identity. It was difficult to wear this back into White society. On the lecture circuit she was on for a few years after her return, it became her meal ticket: People attended both to hear her story (which Stratton ghostwrote, injecting it with a viciously racist depictions of the Mohave as savages who she was only saved from because of her Christian faith) but also to see her tattoo. Later in life when she married and lived in Sherman, Texas, she sometimes wore a little veil covering it.

C&I: How did she adjust after being ransomed back, and how did she spend the remainder of her life?

Mifflin: She attended a two-year teaching college in Albany, New York, while living with Stratton and his family, then married cattle rancher John Fairchild in New York in 1865.

They moved to Texas, where she volunteered in an orphanage. People who knew her said she carried the sadness of her experience for the rest of her life. But she did find happiness with her husband, as a very loving description of him in a letter she wrote to her aunt confirms (it appears in the paperback edition). They adopted their daughter from the orphanage where she worked.

C&I: Some accounts of her life indicate she wanted to return to the Mohave. True?

Mifflin: I believe she wanted to re- turn, or at least have some means of staying in close touch with them after she left. She had an opportunity to escape when the Whipple party came through to survey a railroad route through the Mohave Valley but didn’t.

And as interviews with her after her return to White society confirm, she knew the routes through the area very well, so could have navigated her way out if she’d wanted to.

She was heard weeping night after night after being ransomed back. She reunited with the Mohave chief, Irataba, when he visited Washington, D.C., to meet with Lincoln, and asked for news of her Mohave sister, Topeka.

C&I: What do you think makes the life story of Olive Oatman so compelling today?

Mifflin: First, I have to say it has always been primarily compelling to White people. The Mohave didn’t ever see her as so remarkable — she was just someone who passed through and became one of them. As a piece of literature, her story (first told in 1857 as a pseudo-biography by Stratton) stands in a unique spot on a continuum of captivity narratives, nearly 2,000 of which had been published by the time hers appeared. (Olive’s was one of the last such stories.) They were appealing to the growing number of middle-class women readers in a way fiction wasn’t: They were true stories about women in the wild. The American novel, even though it sometimes incorporated captivity plots, didn’t feature physically adventurous female characters. So women who were confined to lives of domesticity could identify with these protagonists, who were forced to do exciting things normally forbidden to them. And unlike most women’s captivity stories, in which the women were mothers protecting or trying to get back to their children or families, Olive was on her own, with (she thought) no family to return to. Hers was much more like a male adventure story, so it was that much more exciting.

Today, now that tattoo has entered the middle class, people are drawn to her because of the tattoo, which looks so shocking on the face of a Victorian woman. She seems to be experiencing a revival. Just since last summer, my book has been the basis of three pod- casts about her, and people are constantly retelling her story on YouTube and TikTok.

C&I: What really stays with you about Olive Oatman?

Mifflin: She’s a uniquely bicultural American in that she wears the symbol of her adopted nation on her face, emblematizing the kind of cultural collisions this country is built on. No one else wears that kind of literal mark of assimilation.

C&I: What would you like to clarify for people and have them take away from this seemingly singular story in American history?

Mifflin: As compelling as Olive’s own pioneer story is, it’s most important for the way it sheds light on Mohave history and the catastrophic impact of colonial expansion. It’s shocking to see how fast this happened. When the Mohave adopted her, they were a unified nation, secure in their river valley, with all their needs met. But it took only five years after they opened their land to railroad surveyors and other path- finders to be displaced. After 1859, what had been identified as the Mohave Villages was literally scrubbed from maps and renamed Fort Mohave, ironically for a military post erected to protect westward-bound emigrants from the Mohave.

To purchase Margot Mifflin's book, The Blue Tattoo: The Life Of Olive Oatman, visit Barnes & Noble.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian Institution.