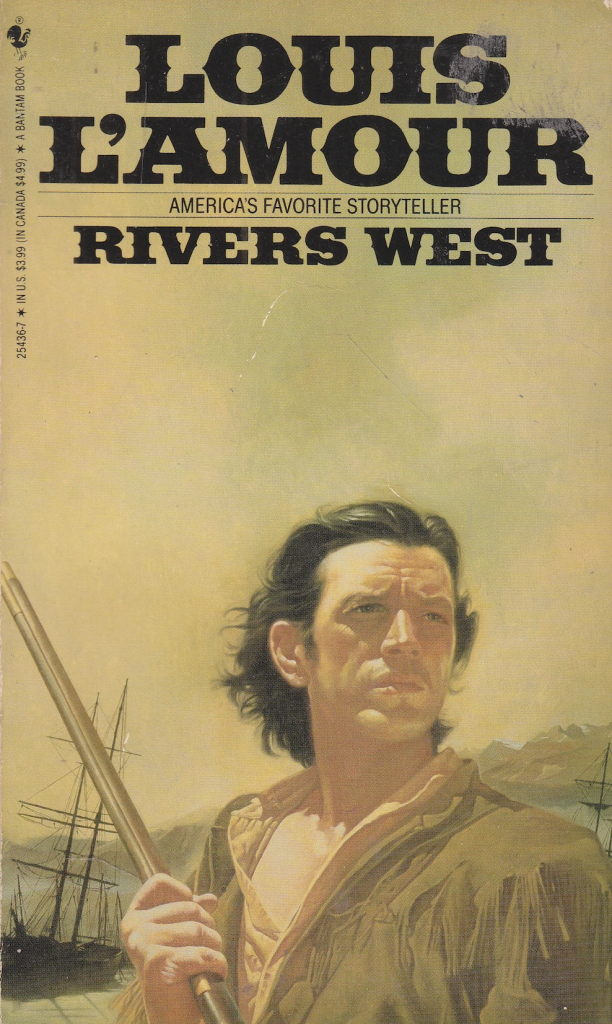

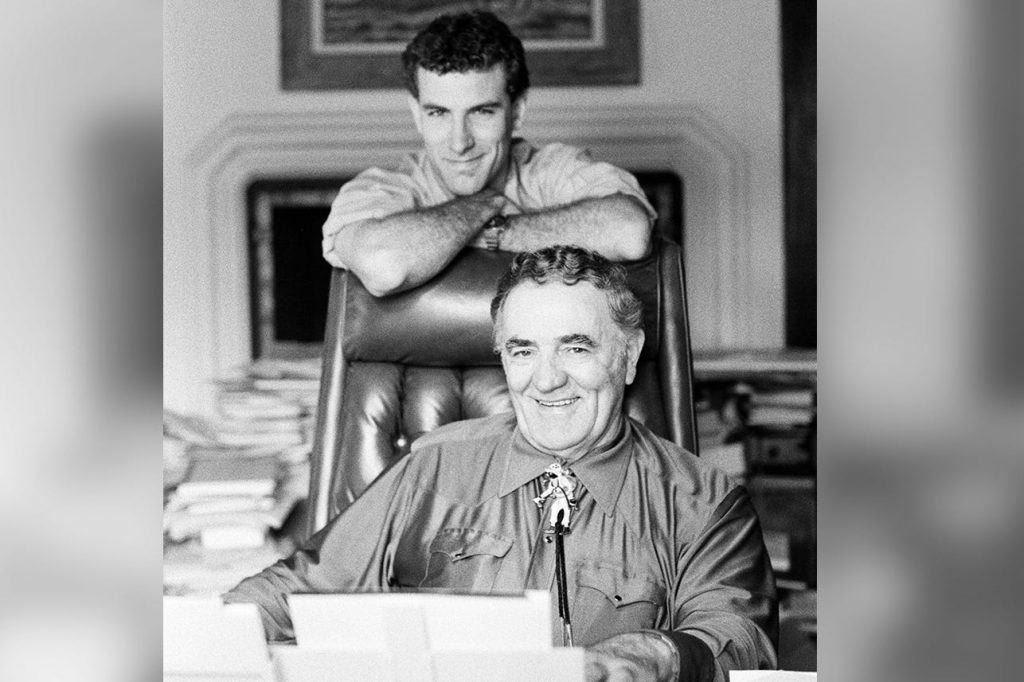

Beau L’Amour joins Writing the West Podcast to explore the newly restored Rivers West and the deeper creative archaeology behind the Louis L’Amour Lost Treasures series.

For fans of Louis L’Amour, the Lost Treasures series has opened a rare window into the legendary author’s creative process — the drafts, the letters, the abandoned openings, and the stories-behind-the-stories that shaped his iconic body of work. In this episode, Beau L’Amour returns to Writing the West to discuss the newest release in the series, Rivers West, a novel with a fascinating editorial history and an equally compelling restoration process. From early 19th-century political intrigue to the challenges of expanding the western genre, Beau reflects on his father’s far-reaching vision, his remarkable discipline, and the behind-the-scenes discoveries that continue to illuminate Louis L’Amour’s legacy for a new generation of readers.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Cowboys & Indians: Beau, welcome back to Writing the West Podcast. Earlier this year, we got to talk a lot about your father’s legacy, your stewardship of his legacy, and we very momentarily touched on the Lost Treasure Series. And this time we get to zero in on Rivers West, which is the latest release in the Lost Treasures series. Why was Rivers West the right title to revisit next?

Beau L'Amour: Well, it’s the one that's being published now. I'm sort of joking. I mean, that's what we're doing. But Rivers West is a really, really good one to talk about because—well, first let me explain what Lost Treasures is, and then you'll see why.

Okay. So the Louis L’Amour Lost Treasures series is first and foremost that I'm going into many of the old Louis L’Amour novels and books of short stories. I think I have done 30 of them now. There’ll probably be a few more. So 30 of the books have a postscript in them. That's kind of like the making-of, or the story behind the story, or stories that are associated with this story that are interesting. And sometimes those will be—well, they're all different.

So sometimes it will be… maybe this is something about Dad doing research on a particular story and I happen to have documents. I have letters that he wrote or received. I have material that he created in one way or another — maybe an early beginning to the story, maybe just notes that he made on it. We have a Lost Treasures that goes very in-depth on Last of the Breed. But the Lost Treasures for Last of the Breed actually includes a short story that he initially intended to be kind of the hinge point, kind of the character development point for that character. And somehow in his enthusiasm for writing the book, he left it out. And when you read it, you kind of go, “Oh wow, this is really this terribly important moment right in the middle of the story” that came from that short story.

Sometimes the Lost Treasures material might be about what happened after the book was written — how it was received, or how the movie was made, things like that. I'll go into whatever it was that happened after we went on and did the book. If there’s something interesting there. Obviously, there isn't something interesting for every single book, or I’d be doing every single book. I don't want to waste anybody's money or try to suggest that somebody buy something where I'm kind of spinning my wheels and making something up to add Lost Treasures material that isn’t meaningful.

In the case of Rivers West — well, let me back up a sec. There's also two books called Louis L’Amour’s Lost Treasures, Volumes One and Two, and those are mostly — there’s some finished stuff in there — but those are mostly unfinished stories. And then after the unfinished story, I will go in and talk about why it's unfinished, what Louis had problems with doing, what he was trying to do by writing that particular thing, how it was going to fit into his career.

In a couple of cases, we have several different attempts at the same story. So you can see the difference between the things he was trying. One of those in there — there's a beginning as a novel, there's also a beginning that's a pilot for a television series, some various other things like that. So the Lost Treasures Volumes One and Two have all of these unfinished works.

And then there's one last book, No Traveller Returns, which is my dad's first novel that was left unfinished and that I went in and did quite a bit of work to finish it up.

So that's how the Lost Treasures series lays out. And Rivers West is a really good one to talk about as a postscript book because it was a novel that was published back in the mid-1970s, and it was very heavily edited. And my dad complained about — I'll go back and tell you the story about this in a second — but Dad complained about that, and there were some adjusting of things that were going on in the publishing situation. He had trouble with several different books that were being edited at that point.

So anyway, with Lost Treasures, I thought, “Well, this is the perfect opportunity to go back and re-edit that book — go back to all the original material that was originally there and look at it and see exactly what he thought the problem was with the editing,” because it was never fixed throughout the years. And I would have the chance to put material back in to fix it up and to try to create kind of a restored version of it.

So of all the Lost Treasures books, it's one of the more… it’s got kind of a more dramatic story behind it. And now I'll pass the baton back to you for a second. If you've got any questions, I can go on from there, but there you go.

C&I: What strikes me initially is that during your dad's lifetime, he went on book tours, he gave some interviews, but especially in the time in which he was writing — that we’re speaking about with Rivers West in the seventies — there was no way for fans to shoot him a Twitter message and say, “Hey, why did you make this choice?” or so on. And it's giving us such a revealing insight into the process, not only of his writing, but also, like you said, the editorial process at the publishing houses and things like that.

Was there anything — whether it be the revisions or maybe conceptual shifts in his writing process — that really made this unique compared to the other Lost Treasures books?

L'Amour: Not necessarily this book, but what you're saying is correct. It's just that the differences are kind of subtle.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Dad was fairly successful writing westerns. He'd written a dozen, maybe a couple more, successful western books. They were selling well, and he wanted to branch out and write adventure stories of different types — historical novels. This is the time period when The Walking Drum was originally written, even though it wasn't published for 25 years.

And he did not have any success in that. He tried to break out, but publishers weren't interested — primarily the publishers. I mean, this is something I've learned in the interim, maybe even since I spoke with you last. The publishers weren't particularly interested because of a thing that had gone on in the book business at this time.

So — paperbacks originally were racked by publisher. So if you went into a newsstand or a drugstore or many bookstores, you would find all of the Bantam books together, all of the Dell books together. And that's how you found your favorite authors.

And by the late 1950s, the paperback business — which really got rolling in the early 1950s — was so prolific, and there were so many titles out there, that they were filling up bookstores. And those racks were becoming really kind of redundant and awkward.

And they decided that they were going to go through a process — kind of amusingly for the late 1950s — called integration. And they were going to integrate all of the different publishers and all of the writers. And from then on, the books would be found in categories based on their genre.

And as soon as that happened, there was a lot of pressure for authors to never change their genre, because otherwise it was very difficult for readers to find them in the bookstore.

And so right at the time that my dad decided, “Okay, I've written a bunch of westerns, now let's experiment with The Walking Drum, now let's experiment with this other thing,” the pressure came on: “No, you can't do that. You just have to write westerns because nobody will be able to find you. It'll be a bust if you do something like that.”

And he was dismayed.

He had been working on a number of projects — some of which we'll talk about later, I think — but he realized the reality of it. And he also realized that he didn't want to compromise the success he'd had. He was in his late fifties or early sixties and was still struggling. He had his first child on the way — and he was in his early fifties at that point — and he didn't want to take too many chances.

So he went back to writing westerns. But he got this idea that what he would do is try to expand the parameters of the western genre. I think his first attempt to do this was Shalako, which was a western about a bunch of Europeans on safari in the West — just like they would be on safari in Africa. And it was a thing that happened, but I don't think anybody had ever written about it before, and it was maybe a little controversial at the time.

The western genre is very, very brittle. Fans do not— they want new material, they want it to be different… and they don’t want it to be different at all. They want it to be absolutely what they expect, and they still want it to be unique and different and entertaining in all those ways.

And so he did this safari-in-New-Mexico story, and it was a little bit controversial at that time. When the movie came out like five years later, it was very controversial. I mean, fans were blowing up over it. And it was also a European film, so it starred Sean Connery and Brigitte Bardot and Honor Blackman — who's not necessarily European, I think she was American — but she had been in a Bond movie.

C&I: By association.

L'Amour: Yeah. And so it caused all this hoopla: “What are all these foreigners doing in a western?” As if nobody from anywhere else ever came to the United States. But anyway.

He started kind of expanding the genre a bit. Then a few years later he did The Broken Gun, which was a modern, early-sixties-set mystery that had kind of a western history to it — an Old West history to it. And then he wrote Riley’s Luck a few years after that, which was a western in which a moderate amount of the action takes place in Europe.

And finally in the early seventies, got around to writing The Ferguson Rifle, which did not occur in Europe or anything like that, but it was set much earlier — just after the Revolutionary War — so it wasn’t a traditional western.

Then he wrote The Californios, which was early California, pre-Mexican-War California. And so again, early time period — and it even contained some science-fiction elements.

So he kept taking the genre and kind of tugging it, tugging it, tugging it — trying to kind of open up a hole that he could drive a more interesting story through.

And eventually he got around to doing what became the first Sacket story, Sacketts Land, which is set in the 1600s, about the first Sacket coming to North America, and then its immediate sequel, To the Far Blue Mountains.

Now, once he'd done that, I think the next one was probably Rivers West. So it's a good moment to discuss this.

Rivers West is also set kind of early. It starts in— I think it starts in Canada. It definitely starts in the Northeast. It's been a while since I read it. I know it's just coming out now. But I did this Lost Treasures and sent it into the publisher, and it kind of got lost for a couple of years. And I called them up at a certain point and was like, “I know I did this. Where is it? What happened?”

And so anyway, it takes place in the 1820s — late 18-teens, early 1820s — and it's kind of referring to an incident in American history that’s really fascinating.

There were several different people who attempted to take over the Louisiana Purchase in the early days — the most notorious of which... and I'm going to tell the craziest version of this story. I don’t know that this is all perfectly historically accurate. I know people have claimed what I'm about to tell, and I'm not swearing to you that it's the most verifiable historical account.

But if you thought American politics was turbulent today, just wait until you hear this.

Thomas Jefferson is president. So this is considerably earlier than my dad's story. This is early 1800s, not 1819, 1820. Thomas Jefferson is president. Aaron Burr is the vice president. Aaron Burr fights a duel with Alexander Hamilton and kills him.

And now the Vice President of the United States is on the run from the authorities in several different states — for both dueling and maybe manslaughter — and is sneaking into the White House to confer with Thomas Jefferson, like going through the back window. And he also had a buddy who was a general — I shouldn’t say “buddy,” he had a guy on his secret payroll, on his bribery list — who was the general who was head of the Department of the West.

And he was vice president, but he was kind of miffed about being vice president, because in those days, the vice president was the loser of the two people who ran. So this would be like Kamala Harris would be vice president today— although he got along with Jefferson.

C&I: What could go wrong.

L'Amour: Exactly. He got along with Jefferson, but he was still burned about not having become a super important person. And so he had this connection with the general who was head of the Department of the West. And that guy eventually was sort of told by Aaron Burr — so the story goes — to foment a war with Spain in the West so that an army would be sent from the United States into the Louisiana Purchase to defend the Louisiana Purchase from Spain.

And then Aaron Burr would somehow go out there, take charge of that army, and turn it into his army — to basically grab the Louisiana Purchase as his own kingdom, literally elevating him to royalty.

As I understand this more radical version of the story, the Zebulon Pike Expedition, for whom Pike’s Peak is named, was actually sent out there as one of these attempts to piss off the Spanish. But at the same time, the general who was head of the Department of the West was taking bribes also from the Spanish. And to keep getting more money, he was making sure that the American patrols and the Spanish patrols missed one another. So he didn't want a war to start — he wanted both sides to keep paying him.

So Rivers West is kind of based on that. The bad guy in Rivers West is a sort of Aaron Burr type of character who is attempting this kind of filibustering, mercenary takeover of the Louisiana Purchase.

C&I: And of course the Mississippi River being a central part of all of that.

L'Amour: Well, it is super important to understand — I mean, this is something that is touched on in my dad's work, and I touched on it a little bit more in the postscript — but I think it's extremely important for people to recognize what we call Manifest Destiny — this basically attempt to colonize the entirety of this swath of North America, basically buying it from France, taking it from Mexico, taking it not so much by force but eventually by kind of coercion the Oregon Territory from Canada or England, depending on how you see that.

So that was also a big conflict in the 1830s — the idea that the United States was going to take Idaho, Oregon, and Washington (modern Idaho, Oregon, and Washington) from Canada — and controlling that space was extremely important strategically. When the United States didn't know who was out there, they weren’t worried about the Native Americans — they were worried about Europeans. They were worried about the French, they were worried about the Spanish and the Mexicans, they were worried about the British particularly. And the idea that there was this vast space that made them vulnerable was probably something that kept people up at night.

And then the Mississippi–Missouri Basin — which is absolutely the most gigantic and productive waterway in the world, maybe second only to the Great Lakes — was… I mean, there had to have been people who saw that and basically said, “Well, look at the civilizations along the Nile. Look at the civilizations along the Euphrates. Think about what modern industry, even 19th-century industry, could do with that waterway, especially in an era without railroads.”

It must have looked like the answer to everything. I mean, nobody knew how to go out and deal with it quite—

C&I: We weren’t sure what we were going to do when we got it, but—

L’Amour: Yeah, exactly. But you look at it and you just kind of go, “Oh no, that is enormous — enormous potential. And if somebody else gets it, we’re screwed.” The United States of that era is a tertiary power at that point.

And when you see the great era of American manufacturing all basically along the Great Lakes, and all of the great farming communities along the Mississippi, you basically see heavy finished goods exiting into the Atlantic and everything else exiting into the Caribbean by water. I mean— enormous. Economically, enormously important.

So anyway, there's a good deal of that in this particular story. It’s kind of about a young man who stumbles upon this conspiracy and does some things to disrupt it. And I've probably gotten somewhat off where your questions were headed. So I'm going to stop a second. What were you asking?

C&I: I did want to back up for a second before we get to Rivers West, which I do have a number of questions about — our protagonist and the other characters. But I think we spoke in our prior interview about how in the early to mid-seventies, there was kind of this buildup to the Bicentennial, which kind of propelled a lot of these stories — your dad’s books that dealt more with, I think, the founding of what then became the frontier, or America during the frontier. Like Rivers West, the early Sackett books.

Do you believe that your dad probably saw that as a great opportunity, given what you just mentioned too about being pigeonholed into that western genre? Was this a prime opportunity for him to delve into some other story ideas that he'd had floating around?

L’Amour: I think he felt the winds of American culture changing. Okay. I'm not going to tell you he had his thumb on the pulse of youth culture in the late sixties or early seventies. But until 1973, we lived in West Hollywood — which was the Haight-Ashbury of Los Angeles, equivalent to Ashbury, East Village, Soho in London, I mean… crazy, crazy, crazy beatnik neighborhood.

And it was pretty clear that the British Invasion fad of rock and roll was changing into something that was much, much more American-roots-oriented. I mean, I can remember walking to school — with my dad walking home from school — along Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood, and you were constantly running into people in fringe jackets and riding boots, and the girls all had Indian braids.

It was… the kind of hippie aesthetic was definitely that kind of thing. And I think from some of that, he recognized that the culture was opening up… that if they could accept hippies as cowboys, then he probably could get away with writing something that took place in the colonies. He might be able to get away with doing The Californios, which has a little bit of science fiction in it.

I think he realized that the old, very straight-laced vision of what had to happen in a western was probably breaking down and he could do more with it at that time.

C&I: And thinking about this particular novel, Rivers West, one thing that really struck me initially — versus maybe some other novels, not necessarily even by your dad — but that didn’t quite fit into the western archetype as strictly as maybe they would have in the fifties, is that the main character, Jean Talon — he’s not even a gunfighter. He’s a shipbuilder.

So I could see from page one a much more… a changed outlook on what the book could be. It starts with this swampy, foggy mystery feel to it. In the opening pages, we have this guy who’s stuck in his head about shipbuilding and all of these great things he can do, and not worried about his gun or anything like that, that we've come to know in these traditional westerns.

How do you see that character and this book fitting into what I think became known as your dad's philosophy of who these frontiersmen were — the types of men who made it in these untamed lands — and now even further back into the early 1820s?

Does that character still kind of fit that mold and philosophy — the same philosophy that guided characters like The Tall Stranger or Conagher? So different… but yet do you still see him fitting into that same philosophy?

L’Amour: Well, he definitely gets in a lot of trouble and has to handle violence and things of that sort. But I think also — Dad, many times when speaking about the West, would kind of downplay the role of many of the things that we just saw way too many times in movies: gunfighters and marshals and all that sort of stuff.

And at the same time, he knew that that was the genre he was writing in, and that those items needed to be used to fulfill the requirements of the genre — at least most of the time.

So his own personal vision of what the West was all about, and what he was writing about, was… it's kind of two different things. One being more historically accurate. I mean, as far as we know, there were only one or two middle-of-the-street kind of gunfights ever. And I think one of them — the Hickok–Tutt fight — was in Illinois or someplace like that. It wasn’t even really quite in the West.

But I think that if he had gone on with his career — if he had lived another 20 years and maintained his health and things like that — I think he would’ve been writing more about other events and other types of people because it had become possible.

I know that he very much wanted to write something that dealt with— I know this because he had issues with the things he had to learn in order to do this, the research he would've had to do. He definitely wanted to write something that was kind of technical about railroading and railroad building. And there were sort of railroad-track-engineering issues and railroad-train-engineering — actually the driver-of-the-train-type engineering issues — that he was struggling with a little bit.

We talked about that, because I'm kind of the techie guy in the family who went out sometimes when he had to know things like that late in his career. I was kind of the guy that did some of that.

I think he was fascinated by the early days of the surveyors — so, pre–Civil War, when they knew the railroads had to go in, but nobody was quite ready to build them.

I'm going to say something — and I'm probably going to get a couple of these details wrong; it's been years since I heard it — but I believe if you're building a railroad track, say you're going to build a railroad track from the East Coast to the West Coast… it can only manage a 2% grade, and there has to be water every 90 miles — thousands of gallons.

And you think, “Yeah…” and you're sort of like, “Okay, that is a connect-the-dots, wild, wild kind of set of demands to put on something.” The track bed has to go someplace where it can handle trains that are many tons. You can't have too many tunnels and bridges — which are too expensive — and you've got to have water.

Now sometimes they would bring the water in on other trains, but you had to have water available, because that’s really what your trains were running on.

And we talked about that. And he was kind of fascinated: “I don't really read these stories about how difficult that job was — but it must’ve been incredibly difficult.”

So like Jean Talon being a shipwright — he wanted to get into some other things like that. I know he wanted to also do work that took place in the era prior to the Civil War, because a tremendous amount of really interesting stuff happened in that time period. But for a long time, it wasn’t really considered to be the “Wild West.” It was something else.

C&I: And you mentioned a minute ago — telling us about the political undertones that were affecting everything at that time period — that’s where I really saw your dad’s philosophy play through with Jean Talon as a character. Even though he’s not the traditional mold of a Louis L’Amour cowboy or whoever the normal fan would assume — it still brings up this idea of: Can you really take the country by force, like Baron Torville, our antagonist? Or do you build it and create it and make something from it, like Jean does?

That struck me, because in a lot of your dad’s books, that same idea comes into play. There’s always this antagonist — whether it’s the neighboring rancher or the outlaw who wants to take what he wants by force — but it’s the cunning, it’s the heart of the protagonist that keeps that at bay and shows another way.

Do you think, looking at all the backstories and Lost Treasures features you've looked at, that this reflects something about how your dad felt about the founding of the nation in that time period? Anything like that you were able to pull?

L’Amour: Oh, I think no question. I mean, first of all, in entertainment, you don't really have entertainment without drama, you don't have drama without conflict, and it’s very often that you don't have conflict without violence.

And so, as soon as you accept that you're doing entertainment, you’re looking at certain types of stories. And the western was driven very heavily into a certain type of story like that. But there were a lot of other things that happened.

And I like the way you presented that contrast between sort of the imperial, the mercenary-imperial version versus the constructive-imperial version — dueling it out in this story and in a more minor way in some of the others.

There is that reality. Yeah.

C&I: And for this story in particular, with the postscript that you're collecting for these Lost Treasures editions — when fans get the book and read this — was there one type of postscript that was more common in this book compared to others, whether it be drafts or letters or things like that?

L’Amour: Well, the thing that really sets this one apart was the fact that it was— so, there were several books — I think it started with Sacketts Land — that my dad and the publisher wanted to have… My dad basically gave his career in the early fifties over to paperback originals. He was happy to work that way, even though you didn’t quite make as much money off the books as you would if you started in hardcover, because the hardcover publishers would keep a lot of the money, and they would keep a piece of the paperback rights and stuff like that.

If you went right to paperback, you kept it all.

So Dad was very happy to go straight to paperback, even though the cover price was less, and you made somewhat less in the early days because of that.

But at this point in his career — 1970s — he was kind of fighting for greater credibility. His sales had just kind of started to go exponential. The really successful part of his career was just starting to hit. And paperbacks didn’t get reviewed. If you wanted to be reviewed, you had to have a hardcover.

And so Bantam and he put together this deal with Saturday Review Press and Dutton’s, I think, to produce some of the books in kind of a limited hardcover release. I think that may have started with Sacketts Land. And so Sacketts Land, then there was To the Far Blue Mountains.

But what happened was — when it went from Bantam, which had, I hate to say, kind of lax editorial standards — to Saturday Review Press, which had kind of more significant editorial standards… but I'm going to say maybe not better editors.

So I have a lot of questions about how these people were doing things. I know the problems they were trying to fix, and they were right to fix them — the ways they went about it, I think, were kind of a mess.

And they kind of made a mess out of To the Far Blue Mountains, and then they kind of made a mess out of Rivers West.

My dad thought — this is not true — but when he saw it, he was sure they had cut a hundred pages out of it. Now, like I said, they didn’t. That was kind of his emotional reaction to it. But they had gone in and tried to fix things that needed to be fixed, and they had done it — particularly in my opinion — in a very disruptive way.

When I saw in correspondence — which I include in the postscript — that he thought a hundred pages had been cut out, I was like, “Oh boy, I've got to go back in and re-edit this.”

So I went back to the original manuscript, which has got markings all over it. I mean, it's got several different generations of publisher markings in there — very, very hard to figure out what happened, what happened when.

C&I: Whose pen is whose.

L’Amour: Exactly. Because somebody had taken a bunch of stuff out, and then before it was initially published, certain things had been put back in. And this didn’t have anything to do with my dad. He didn't even know it was happening at this point.

C&I: He was three books in.

L’Amour: He was way on into the future. Exactly.

And so I went back, put everything back in, went back through and re-edited it, and discovered what they were trying to fix.

I think this book was being written a little bit over a year and a half earlier, when we made the move from our home in West Hollywood to our home in West L.A. near UCLA. And that was a very— My dad tried to keep working through that, but it was really disruptive. And then he didn't have a good place to work for several years after we arrived there. And it was kind of a mess, which I describe — hopefully in somewhat humorous manner — in the postscript.

But he got confused about where he was geographically, which is almost never… I mean, when I see my dad kind of get a little whacked out about what's going on geography-wise, that’s the sign that something is wrong.

And so I had to tweak some of that. I had to make some cut-and-fills in some other places. But the main goal was to get absolutely everything that I could possibly get back in — that made sense — back into it.

And then the problem went on. We went one more book beyond that to Fair Blows the Wind, where again my dad got confused — Fair Blows the Wind occurs before Sacketts Land, but in To the Far Blue Mountains, he had tried to unify the two stories and the timeline didn't work.

And so if you read through the postscript to those stories — I think the postscript in that one is in To the Far Blue Mountains — you'll find that I had to go in and make some changes. And then all of the changes that I made are pulled out, and they’re put in the postscript so you can see exactly what happened. But there was a little straightening out of things that occurred.

But all of that stuff was happening — all three of those books were happening — during the move, in different stages.

C&I: Yeah, it's amazing that you can see — having lived with him and lived the life — that you can go in and see, “Wow, this affected this, and this changed that.”

L’Amour: Well, I was there. And he kept a journal that was pretty up — maybe three times a week, sometimes four or five times a week. And it doesn't necessarily refer to these things but you can tell what’s happening. You can tell what’s happening in his life, you can tell what he's struggling with. And same thing with some of the correspondence.

So I've got all that information.

So recreating Louis L’Amour’s Lost Treasures is like the professional biography of Louis L’Amour.

I'll do a biography one of these days. It’s coming up — a kind of conventional one. But this is all the material I never would have had a chance to put in a conventional biography, because I would have to tell the story — I'd have to tell the story he was writing — and then tell the things that were about it, which would just be incredibly time-consuming.

And so it’s much better that it goes right there with the thing that you're reading, so you understand these things occur.

C&I: There was a quote I saw, maybe it was on the blurb of this book — about the Lost Treasures series being kind of this “excavation of creativity,” which I love. And I think so, because as a casual reader of Louis L’Amour, someone might say, “Wow, he's been to all these places,” or “He's a student of history,” or “He's a great entertainer,” and each person kind of takes their own sense of what his goal was with these books.

For me — I think it's definitely this person with such a huge imagination for history can really place himself in these time periods… and then unfortunately has to come up with a story so all the other people like myself can understand it through.

And now that you've done this for, I think you said, 30 books… what has the Lost Treasures series taught you about your father’s — at least about his process of building stories? From the research, the travel, the intuition — what has that taught you about how he went about these stories?

L’Amour: Well, I think the thing — that whole history that I described about sort of changing and stretching the western genre — I didn't know that before. I got partway into this and I was like, “Oh my God.” It’s like, what a vision. And a man who — probably coming up with that idea in his maybe late fifties — then saying, “I'm going to take 20 years to do this.”

I mean, you just kind of look at it as sort of… that kind of vision of going forward. That idea that he was going to live to get to the end of it — which he did. I mean, in the last few years of his life, he published a Cold War thriller. He published science fiction. He published The Walking Drum finally.

And it's just like — what a vision. What kind of… almost like what courage to just say, “I'm going to invest the whole rest of my life in making this slow, kind of incremental change that doesn't rock the boat and keeps me financially solvent,” and things of that sort.

It was very, very impressive. I mean, I have to say — I always had a lot of respect for him, but I had a lot more respect for him as I not only saw that plan play out, but saw kind of these incremental mentions of what he was doing.

There’s no place where he just says, “This is what I'm doing.” It kind of dribbles out through hundreds of pages of journals and correspondence, and things like that. And so that one was probably the most kind of breathtaking vision of what he was up to.

C&I: Well, and one question I've been dying to ask you too is: if your dad was here to see all of these discoveries of letters and how you've kind of taken all— what do you think he'd make of all that? Was he the type that didn't want his letters written or read or anything like that?

L’Amour: No, think he'd be fine with that. I think he would very much rather be the guy who was still creating enough new stuff so that nobody cared about that. He was always about the new thing. He wasn’t necessarily a guy who— he wasn't going to make his career out of revisiting his career, that is for sure.

And so, did he have some kind of sense of wanting all these things to be private? I don't know. I don't think so. I don't think he was really worried about that kind of thing. I just think he was all about momentum.

C&I: Well, we’re glad he was, because there’s no dearth of Louis L’Amour books to fulfill your appetite, for sure. And as you've mentioned in this podcast — beyond just traditional westerns, the spy thrillers and science fiction and all the others. And even just myself — fans of even the early days of short stories taking place in far-off exotic locales and all of World War II and all of that, which is great too.

And so, you mentioned you've got, I think, a couple of books left in the series to finish up, that you've got enough for. I'd love you to talk about the series and what that conclusion might look like. And then if we've got any new works — you mentioned a book next year as well.

L’Amour: So, on more Lost Treasures… it’s like I write these things and I send them to the publisher, and then they bring them out when they feel like bringing them out. We try to get two of them out a year, and I'm never exactly sure what schedule they're on.

That’s how we lost Rivers West for a couple of years because— So I know I've got one for Son of a Wanted Man that's coming out pretty soon. And then I had to dive into doing some kind of archaeological work on the Sacketts recently, and I noticed that there's probably one or two more Sacket stories that I could do a Lost Treasures on.

As I said earlier, I don't ever like to do these unless I feel like I've really got something significant to say. So I don't know. There might be four more. There might be five. We might end up with 35 of them in total.

And then the new book — so, I don't have a contract for this yet. It has been submitted to Random House. I'm hoping for the best. Everybody's going, “Oh yeah, next year.” But this book is tentatively titled Sky Ring Water.

I say tentatively titled because the publishers always want you to keep the title open until the last minute, in case they've got another book with a similar title. Then they're going to say, “Hey, one of you guys has got to change something so that we don't have two books that have almost the same title coming out at the same time.”

When you're dealing with a publisher that publishes thousands and thousands of books a year — several books a day — it's kind of a big deal.

Tentatively titled Sky Ring Water, it is post-war, kind of early 1960s — like 1960, 1961 — Cold War thriller, about a couple of arms dealers in Spain who get into a situation that is way, way, way over their heads, and end up being kind of hunting for an amazing treasure, and being hunted all through what I kind of jokingly call the Nazi diaspora — the places where the Germans escaped to.

So places like Spain and Egypt and Venezuela and Argentina and Chile. And it deals with a lot of World War II history and postwar kind of Cold War tensions and stuff like that. And so hopefully it will be a very interesting book.

This is a book my dad left behind. He was never very happy with it. When he was having trouble with The Haunted Mesa, he kind of dusted it off and showed me what he had of Haunted Mesa and what he had of this. And he was going, “Which one should I go to?” And I really encouraged him to keep going with Haunted Mesa.

But I said, “There are some changes you could make with this — some of them along the lines of other stories that you wrote, kind of more World War II adventure stories that you wrote.” I said, “You could leverage some of the stuff in these other stories and turn this into one of these kind of international thrillers — which, in the eighties, you had Frederick Forsyth and Jean Ray and Clive Cussler and all these guys doing that kind of stuff. It was a very common thing.”

I mean, Last of the Breed was his first step into that particular market. And so the idea was to basically recreate this as a follow-up. It's not a sequel in any way — there are no characters that are the same — but a follow up in the same vein as Last of the Breed.

And the people who were involved in this book — I mean, the people who helped us out, who helped my dad and I out when we first started talking about it, and then the people who helped me out with it afterward — the acknowledgments to the book are crazy. Okay?

I’ll break one of the dedication things — so, the book is dedicated to several people, but one of them is Thomas O. Paine. Tom Paine was the head of NASA during the Apollo Project. And Tom helped out.

Tom had been an engineering officer on American submarines, and then the prize captain for the largest Japanese submarine that was built, that was brought back to Hawaii and investigated and then taken out and sunk before we were required to hand it over to the Russians.

And so he had this interesting background of submarines and then space later on in his career. But Tom was a big help with some of the submarine stuff that’s in this story.

And there’s a bunch of people of equal kind of historical import that had some effect on us being able to finally produce it.

That one might be a postscript section as well. Like I said, it's got a postscript and it’s got acknowledgments that aren’t just a list of names — I kind of explain what role everybody played, and there's a lot of really, really incredible people that helped out.

C&I: Beau, it’s been great to talk to you. We could talk forever about your dad’s work, and we’re glad to keep having you back on as new books drop and new projects are great, and we’re excited to see the next one.

And Rivers West — available now. I think it just came out about a month ago now — so available in stores. So readers and listeners should go pick that up, and we'll look forward to seeing you the next time.

L’Amour: Thank you so much.

Find your copy of Rivers West at your local independent bookstore and explore more about Louis L’Amour’s Lost Treasures series at louislamour.com.