The Academy has rarely bestowed the Best Picture award to our favorite movie genre.

Our hopes were high, but ultimately dashed, when Killers of the Flower of the Moon was nominated in the Best Picture category of last year’s Academy Awards. Had it won — Oppenheimer ultimately brought home the gold — it would have joined an elite group of movies. Until now, only three conventional Westerns and one modern-day Western have received that honor.

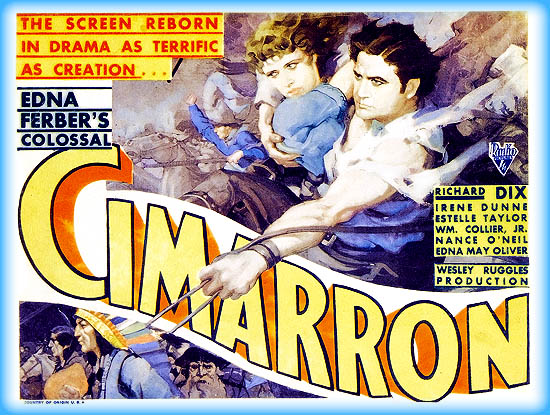

Although director Wesley Ruggles’ sprawling 1931 drama based on the 1930 novel by Edna Ferber (Giant) might seem creaky and dated to some contemporary viewers, Cimarron — the first Western to receive the Oscar for Best Picture — greatly impressed critics and audiences during its initial theatrical run, and has continued to influence other Westerns for generations afterwards.

The massive spectacle of the opening scenes, depicting the frenzied launch of the 1889 Oklahoma Land Rush, raises expectations for an epic as mammoth as such silent era classics as Birth of a Nation (1915) and Ben Hur (1925). And the production values are of a similar scale as the movie charts the growth of Osage, Oklahoma from a late 19th-century boomtown to an early 20th-century metropolis. For the most part, however, Cimarron remains intimate and tightly focused as it details the exploits of Yancey Cravat (Richard Dix), an idealistic lawyer and newspaper editor eager to establish an inclusive community — even if his chronic wanderlust often takes him far from home and his not-infinitely-patient wife Sabra (Irene Dunne).

Cravat is unapologetically progressive, quick to defend a woman (Estelle Taylor) whose checkered past leads to her being branded a “public nuisance,” and steadfastly on the side of newly oil-rich Native Americans threatened by rapacious white land-grabbers. (Yes, it’s rather startling to note the similarity of this particular subplot to Killers of the Flower Moon.) But, to be brutally honest, Dix plays the character as more self-absorbed than selfless. It’s easier to sympathize with Dunne as his hard-pressed wife, whose evolution from close-mindedness to social consciousness while dutifully running her husband’s newspaper during his extended absences is by far the most fascinating narrative thread in the movie.

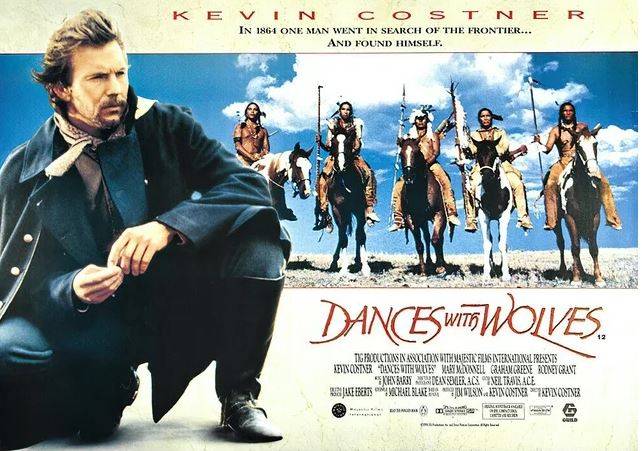

As David Hofstede wrote for C&I on the 30th anniversary of Kevin Costner’s 1990 Oscar-winner, Dances with Wolves is at heart “the redemption tale of John Dunbar, a suicidal Union Army officer befriended by the Lakota Sioux. He begins a new and better life in their company, one that becomes threatened by the Army he left and the Pawnees who are warring with the Sioux.

“What made Dances With Wolves so groundbreaking was its portrayal of the Lakota and the attention to detail devoted to their lifestyle, culture, and language. For authenticity, Costner hired a teacher at South Dakota’s Sinte Gleska University to translate more than a quarter of the script into the Lakota Sioux dialect spoken in the 1860s.

“Roger Ebert gave the movie four stars, describing it as ‘a simple story, magnificently told ... [with] the epic sweep and clarity of a Western by John Ford’ and lauding it for seeing the Sioux ‘as people, not as whooping savages in the sights of an Army rifle.’ The audience, he writes, gets to know many members of the Sioux tribe, especially Kicking Bird (Graham Greene, who was nominated for Best Supporting Actor); Wind in His Hair (Rodney A. Grant); and the old wise chief, Ten Bears (Floyd Red Crow Westerman). ‘Each has a strong personality; these are men who know exactly who they are ...’”

Costner gambled a lot on the production of Dances with Wolves. And he’s currently playing for even bigger stakes as he tries to complete his four-part epic Horizon: American Saga. Nice to see a Western fan who’s still crazy after all these years while ignoring the naysayers and second-guessers to keep Westerns alive and well.

The retired gunfighter who must return to his bloody business one last time. The hotheaded youngster who must back up his bragging when push comes to shove. The small-town sheriff who must face down the hired killers riding his way. The brutally wronged woman who must rely on the firepower of a steely-eyed stranger. Unforgiven abounds in the time-honored archetypes that have been the staples of Westerns since the heyday of Tom Mix. Which isn't at all surprising, considering the 1992 movie — the last traditional western to win the Academy Award for Best Picture — came to us from Clint Eastwood, who played a major role in demythologizing many of these elements for the better part of four decades.

First as an actor, in such films as A Fistful of Dollars and Hang 'Em High, and later as his own director, in star vehicles such as High Plains Drifter and The Outlaw Josey Wales, Eastwood upended clichés, sullied stereotypes, and challenged assumptions — sometimes in dead seriousness, sometimes with sardonic humor. In Unforgiven, however, Eastwood ventured even further into the dark underside of the Western mythos, and to the very top of his form as an actor and filmmaker, while telling the violent tale of William Munny, a notorious gunslinger who harbors no illusions about the high price of taking lives. This is a great movie, and a major source of its greatness is Eastwood’s and screenwriter David Webb Peoples’ darkly ambiguous view of the very things that made most of us so fond of Westerns in the first place.

It’s worth noting, by the way, that in the 30-plus years since Unforgiven was released, Eastwood has not returned to the Western genre, either as actor or director. (As much as we enjoyed it, Cry Macho does not really count.) Perhaps that’s because, in the wake of this magnum opus, he feels there’s nothing left to say, nothing new to add. So he’s leaving it up to others to carry the torch.

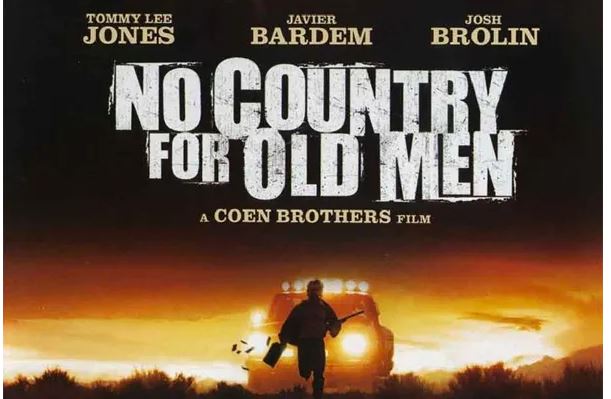

Not a traditional Western, to be sure, but Joel and Ethan Coen’s 2007 neo-Western, based on Cormac McCarthy’s 2005 novel of the same name, is a fascinating and frequently shocking drama of fate, conscience, and the intractable nature of evil.

No Country for Old Men traces the convergence of three disparate lives in 1980 West Texas: Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a Vietnam War veteran who happens upon a humongous stash of money near a dying man in the desert, and makes the fatal mistake of keeping it; Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem, winner of an Oscar as Best Supporting Actor), a relentless mob hit man who’s determined to retrieve the loot and make Moss pay for his mistake; and Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), a sheriff who comes to fear that his dedication and good intentions will ill serve him in a world where wickedness is ascendant.

The downbeat ending proved problematical for some viewers — especially since the Coen Brothers denied us a scene in which we actually see the largely sympathetic Moss die. (His death occurs off-camera, and is referenced almost as an afterthought.) But Brolin embraced the bleakness. “You got so into the character—whether you fell in love with the character or appreciated the character or wanted the character to continue—and then he’s just taken away, and you get upset,” he said in a 2008 interview. “But that’s how we experience things like that in real life. My mom died the same way. One day, I talked to her — just hours before she died, I talked to her —and everything was normal, she was talking and laughing. And then, before I knew it, I got a call telling me she hit a tree with her car, and that was it. So for me, it was a very personal parallel when I read the script.”