A comprehensive retrospective showcases the work of the groundbreaking Indigenous artist.

It was game-changing when the West came east in the exhibition Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, which opened at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art in 2023, establishing Smith (Confederated Salish, Kootenai) as the first Native American artist with a retrospective that the prestigious institution has itself organized. Show curator Laura Phipps believes Smith just might be the most important Native artist alive, having had almost 100 solo shows and major museum acquisitions.

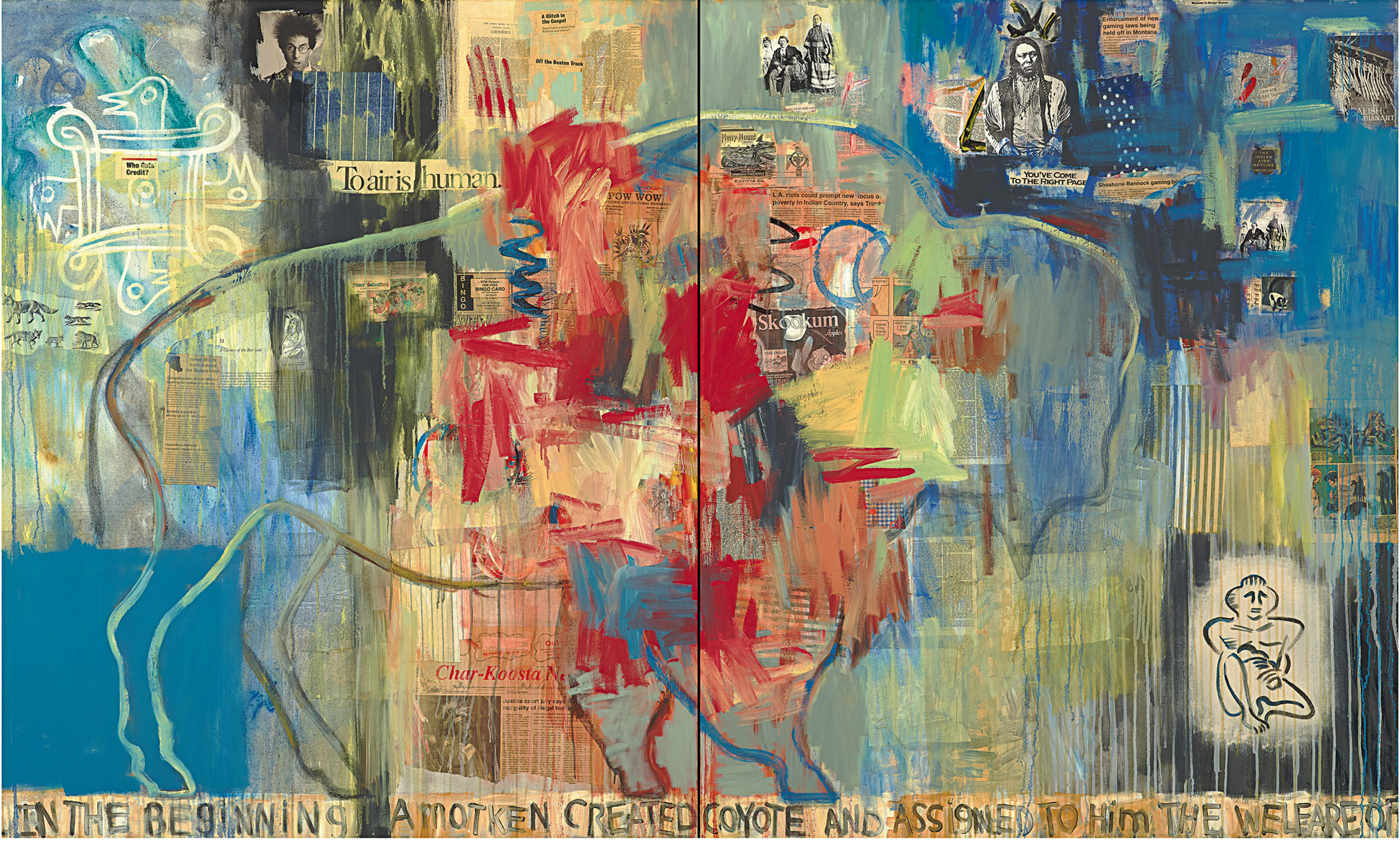

Genesis, 1993. Oil, paper, newspaper, fabric, and charcoal on canvas, two panels, 60” Å~ 100”.

Genesis, 1993. Oil, paper, newspaper, fabric, and charcoal on canvas, two panels, 60” Å~ 100”.

“She’s both the most prolific and the most influential artist of her generation, and that has meant that there are subsequent generations of artists that have platforms that allow them to also be prolific and influential,” Phipps says. A curator herself and an activist, Smith recently put together The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans, a show of nearly 50 intergenerational Indigenous artists, for the National Gallery of Art, on view in Washington, D.C., through January 15.

Smith, now 83 and still working at her studio in Corrales, New Mexico, is known for her abstract expressionist and modernist mixed-media paintings that emphasize Indigenous presence. She places newspaper clippings, found images, and fabric within the same frame as larger painted icons to express the pro-Indigenous, eco-aware mindset that she’s referred to as her “rap.” For Smith, the political is personal. “Her politics are really based on understanding the importance of land and also this nonhierarchical relationship between humans, plants, and animals,” Phipps says.

Survival Map, 2021. Acrylic, ink, charcoal, fabric, and paper on canvas, 60” Å~ 40”.

Survival Map, 2021. Acrylic, ink, charcoal, fabric, and paper on canvas, 60” Å~ 40”.

No doubt considering Robert Rauschenberg’s newspaper collages, Jasper Johns’ abstracted map paintings, and Andy Warhol’s advertising iconography, Smith builds on art history by fusing it with her ironic messaging. Take her repurposing of the U.S. map, sometimes adding to it with clippings, sometimes flipping it sideways, inevitably diminishing its dominion. These pieces convey a message of stolen land, she told CBS News’ Sunday Morning. “I used clippings to show that Indian people do live here,” she explains in the segment. “We’re still here, right? We are here.”

Born in 1940 on the Flathead Reservation in Montana, Smith and her sister were raised by their horse-trader father after their mother left. When a teacher told Smith she drew better than men but couldn’t become an artist because she was a woman and needed to know her place in life, Smith got an art-education degree instead, married, and had two sons. It took until her 30s for her to pursue an advanced art degree at the University of New Mexico. She applied three times before gaining admission.

[1] Survival Suite: Tribe/Community, 1996. Lithograph with chine coll., 36 1/16” Å~ 24 7/8”. [2] The Vanishing American, 1994. Acrylic, newspaper, paper, cotton, printing ink, chalk, and graphite pencil on canvas, 60 1/8” Å~ 50 1/8”. [3] Survival Suite: Humor, 1996. Lithograph with chine coll., 36 1/8” Å~ 24 13/16”.

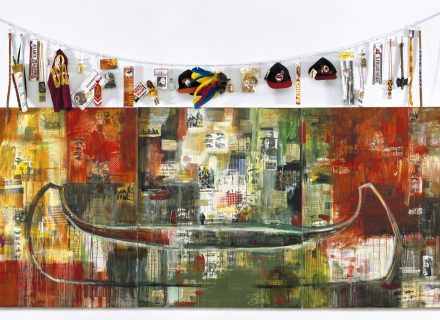

Among the artworks in the 130-piece Memory Map show are two collaborations with her son Neal Ambrose-Smith, one of which is a poignant installation of a canoe filled with plastic water bottles, single-use plastics, wooden crosses, and hypodermic needles. “It’s piled high with all these things that are the product of colonization: the inequities of trade, the disruption of traditional foodways like the bison being replaced with government rations like Spam,” Phipps says. “The loss of land and displacement that disrupts your ability to gather plants to practice traditional medicine. The introduction of Christianity, which had mixed but many negative effects within many tribes. So piling the canoe with the refuse and product of all this colonization, they’re attempting to trade it back.”

War Horse in Babylon, 2005. Oil and acrylic on canvas, two panels, 60” Å~ 100”.

War Horse in Babylon, 2005. Oil and acrylic on canvas, two panels, 60” Å~ 100”.

Canoes appear as frequent imagery in Smith’s work, having been significant to American Indian trade routes. “She sees her work as an artist as a continuation of that tradition of trade,” Phipps says. “As an artist, she trades in ideas. So the canoe is important for her to use. Canoes move things, and she’s moving ideas throughout the world using this icon.” Horses appear in Smith’s art as a personal reference and emblem of mobility. Bison signify a source of food, shelter, and clothing that was targeted by the U.S. government to displace the Indigenous population.

Over the four years that Phipps worked with Smith on the Memory Map exhibition, she has learned that Smith — who looks the artist, often clad in jeans, boots, and a black brimmed hat — drinks strong coffee, has a good energy level, and is dedicated to advocating for other Indigenous artists. But the most potent conveyance of her presence might just be in her work and what Phipps has observed when people stand in front of one of her works. “You see people putting together in their minds what it is that an artist can do with their work, and what they can learn from these beautiful and complex paintings.”

This article appears in our January 2024 issue.

The exhibition Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map is on view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Fort Worth, Texas, through January 21, 1924. It travels to the Seattle Art Museum February 29, 2024–May 12, 2024.

Images: Courtesy of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. Photograph courtesy of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.