Former professor Art T. Burton gives us the rundown on the man behind the legend.

The curator of collections and exhibits at the new U.S. Marshals Museum in Fort Smith, Arkansas, openly remarked that Bass Reeves was the most important deputy U.S. marshal in the history of the U.S. Marshals Service. His main area of operations was in the Indian and Oklahoma Territories, and he did some work in western Arkansas, northern Texas, and possibly Kansas. From 1875 to 1907, Reeves was a commissioned deputy U.S. marshal. He was one of the first, but not the first, African Americans to hold a commission west of the Mississippi River.

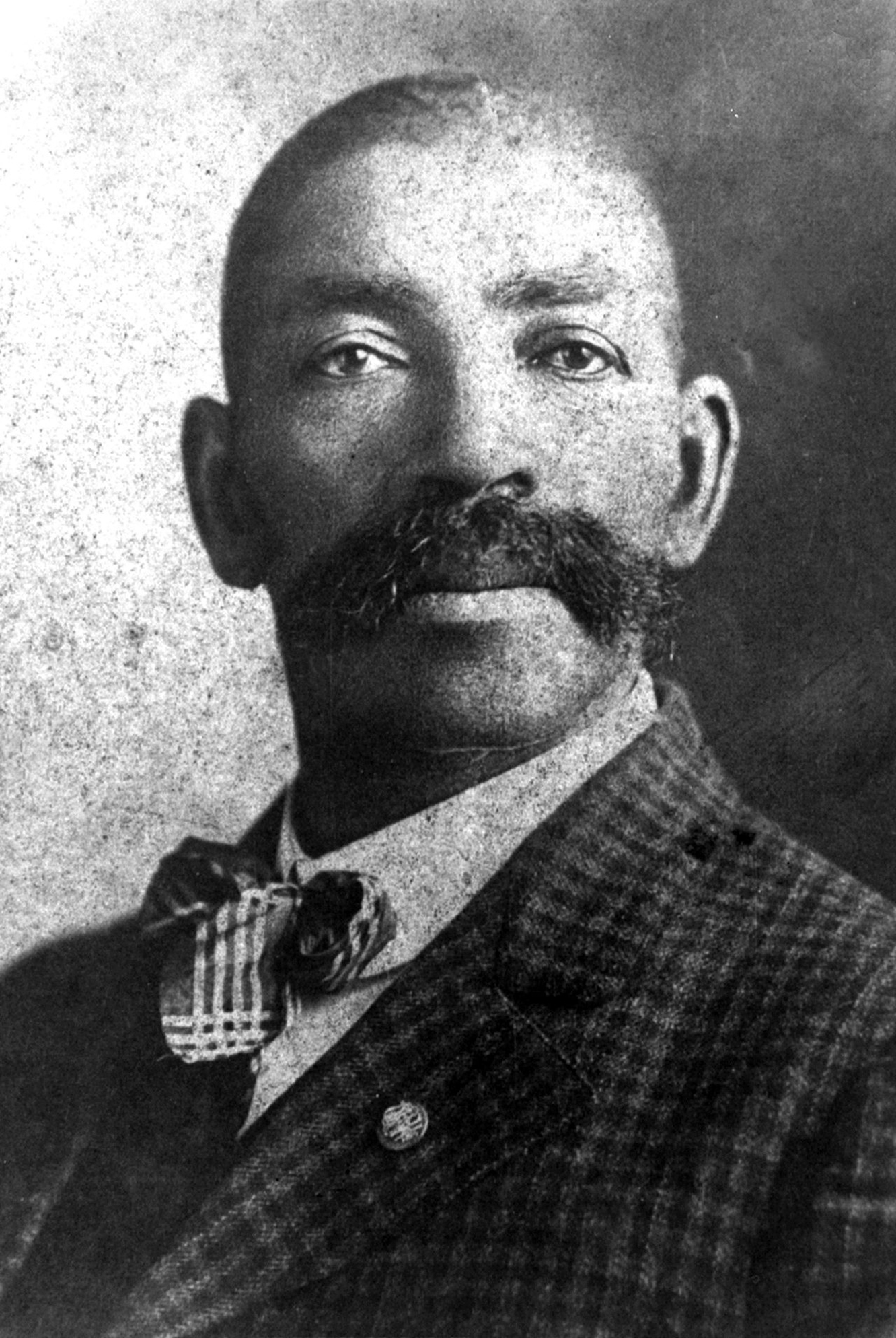

Photograph of Bass Reeves (Courtesy of The Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries).

Photograph of Bass Reeves (Courtesy of The Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries).

I am well-acquainted with his illustrious career. I first wrote about Reeves in 1991. I followed with a biography on Reeves in 2006, which was updated in 2022. My research documented a large amount of information about the man and the legend. Some of his story is well-known to history aficionados. Born into slavery in Arkansas in 1838, Bass and his family were owned by Arkansas state legislator William Steele Reeves, hence the last name. Kept in bondage by William Steele Reeves’ son, Texas sheriff and legislator Col. George R. Reeves, Bass was forced to accompany the son as a body servant when he joined the Confederate Army. Sometime during the Civil War, Bass managed to flee, some say to the Indian Territory, where he lived among the Cherokee, Creeks, and Seminoles until slavery was abolished and he became a freedman. Following the Civil War, he returned to Arkansas and served as a scout and guide for federal lawmen working the Indian Territory until 1875, when federal judge Isaac Parker appointee James Fagan hired 200 deputy U.S. marshals to cover Indian Territory and recruited Reeves, who could speak several Native languages. Fagan was authorized to hire 200 deputies, but there were never more than 50 deputies at any one time for the Fort Smith federal court.

The rest is not only history, it’s also now the subject of a new series created for television by Chad Feehan and executive produced by Taylor Sheridan and star David Oyelowo, Lawmen: Bass Reeves. Reeves also is featured prominently in the new U.S. Marshals Museum in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Statue celebrating U.S. Marshals in front of the U.S. Marshals Museum in Fort Smith, Arkansas

Statue celebrating U.S. Marshals in front of the U.S. Marshals Museum in Fort Smith, Arkansas

However much is uncovered about this remarkable man, I have learned over the years that there is always something new to learn concerning Reeves’ outstanding life of law enforcement. That fact was reinforced this past spring when I was contacted by a Houston police officer who works in the training division of the Houston Police Department Museum. The officer informed me that he enjoyed reading my biography on Reeves but was surprised I left out the “Houston” story. I was completely caught off guard and asked him to send me the information. Soon, I received articles he sent from the Galveston, Texas, and Houston newspapers concerning a murder case from 1897.

From 1893 to 1897, Reeves worked for the Eastern District of Texas Federal Court in Paris, Texas. Houston officials needed help investigating a murder that had taken place, and in 1896, the U.S. marshal in Paris sent Bass to Houston to work undercover. Bass assumed a fake identity as a fugitive on the run and befriended the suspect in the murder case. For three months, Bass traveled with the suspect from Houston to the Indian Territory, then to Dallas and Shreveport, Louisiana, to Marshall, Texas, and back to Houston. Reeves was able to get a confession during his travels with the suspect and testified to the man’s guilt at the murder trial. Subsequently, the man was convicted for the crime. Bass had solved yet another crime in his long career.

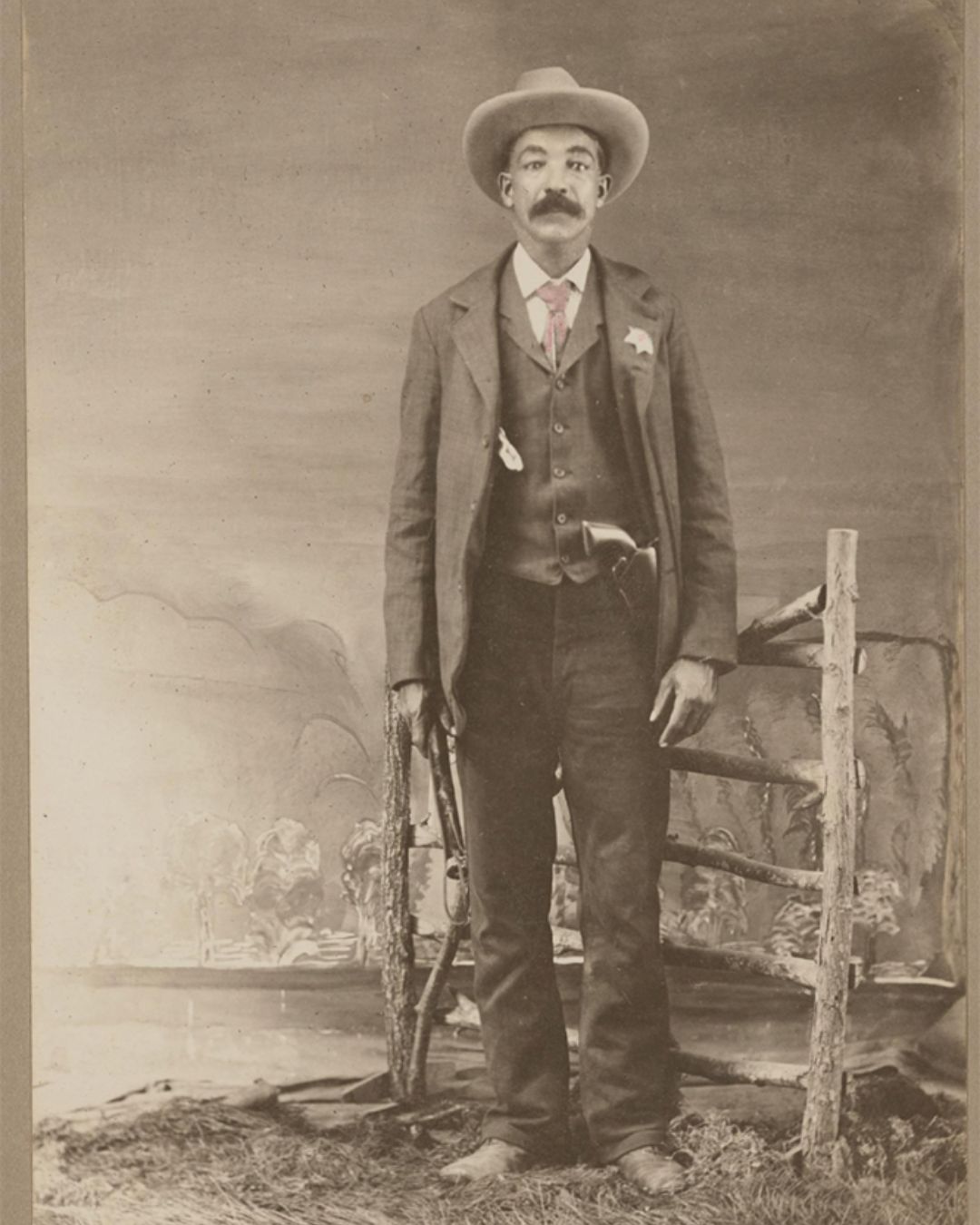

Photograph of a Black law enforcement officer taken in Perry, Jefferson County, Kansas, ca. 1902, by E.L. Goff, long and widely purported to be Bass Reeves, but not disputed by several experts (Courtesy of Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. 2020.10.14).

Photograph of a Black law enforcement officer taken in Perry, Jefferson County, Kansas, ca. 1902, by E.L. Goff, long and widely purported to be Bass Reeves, but not disputed by several experts (Courtesy of Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. 2020.10.14).

I have written and spoken about the uncanny resemblance Reeves had to the Lone Ranger of radio and television fame. We can’t prove that Reeves was the inspiration for the fictional character, but he is the closest person in real life to resemble the “Lone Ranger.” Reeves had an American Indian companion and aide on many trips into the Indian Territory, he handed out silver dollars, he rode a white horse during one period of his career, he regularly worked in disguise to catch fugitives, both were from Texas, and the Lone Ranger’s name was Reed.

The model for the Lone Ranger or not, Reeves’ devotion to duty is legendary. He arrested his own son for murder and the minister who baptized him for selling illegal whiskey. During his long career, Reeves arrested over 3,000 felons who broke federal law. At his death on January 12, 1910 in Muskogee, Oklahoma, numerous newspapers stated he had killed more than 20 men in the line of duty.

For me, Bass Reeves is the greatest frontier hero in United States history.

Read our Bass Reeves Special — including an interview with David Oyelowo, The Superhuman Strength of Bass Reeves, and our Sneak Peek of the New U.S. Marshals Museum.

This article appears in our January 2023 issue.

Art T. Burton is a retired professor of history at South Suburban College in South Holland, Illinois. He is the author of Black Gun Silver Star: The Life and Legend of Frontier Marshal Bass Reeves; Black, Buckskin, and Blue: African American Scouts and Soldiers on the Western Frontier; Black, Red, and Deadly: Black and Indian Gunfighters of the Indian Territory, 1870–1907, and Cherokee Bill: Black Cowboy, Indian Outlaw.

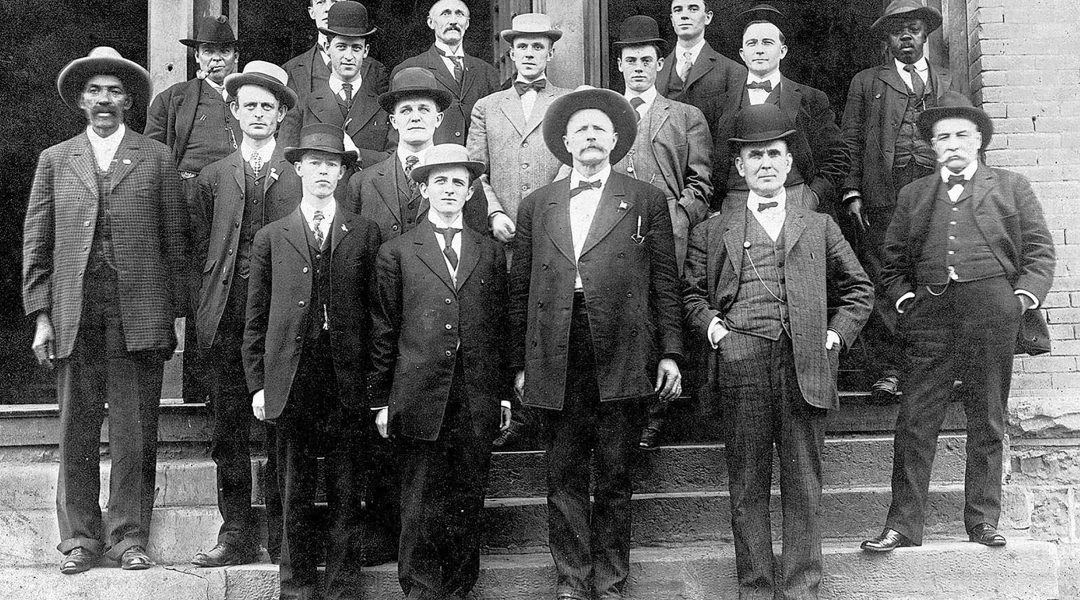

Lead Image: “Federal Official Family” group photo (Bass Reeves far left), ca. November 16, 1907.