It takes a lot of hats to keep an independent league baseball club chugging full steam ahead to deliver smiles for fans.

Rory Niewenhous is nowhere to be found. The man I was supposed to be meeting at The Depot at Cleburne Station, the home of the Cleburne Railroaders, an independent league baseball team that plays in the American Association, wasn’t there. Admittedly, I was a little early, but I figured he would be at the stadium already on a game day. So I called him.

“Hey, sorry. I will be there in a few minutes. I’m finishing up something at the embroidery shop,” Niewenhous said.

A big sponsor was bringing more than 1,000 fans to the game the next night, and Niewenhous was having a custom jersey made for the head of the company. Though his actual title is partnership marketing manager, Niewenhous, and everyone else involved in an independent league baseball team, must wear many hats every game day to put smiles on the faces of fans, even if that means finding the nearest embroidery shop hours before the first pitch.

I’ve driven to Cleburne, a town 30 miles south of Fort Worth, Texas, to explore the ins and outs of what it takes to run a team like the Railroaders. If Niewenhous and others have to wear several different hats, I wanted to see how many I could wear in the course of one game day.

The first hat I put on was the red Railroaders cap they gave me when I arrived. The team was founded in 2017, but the original Cleburne Railroaders started in 1906, so this iteration of the franchise proudly displays the year on their logos and jerseys. They play in the American Association, an independent minor league unaffiliated with Major League Baseball.

Niewenhous, along with interns, front office staff, and others, make everything run on game day to entertain the fans who show up to the 1,750-seat stadium in Cleburne, a town of 30,000 people. Though the town itself isn’t large and isn’t too far from Arlington, where the Texas Rangers play in the major leagues, Cleburne is a great location for fans of baseball from the many nearby smaller towns and communities.

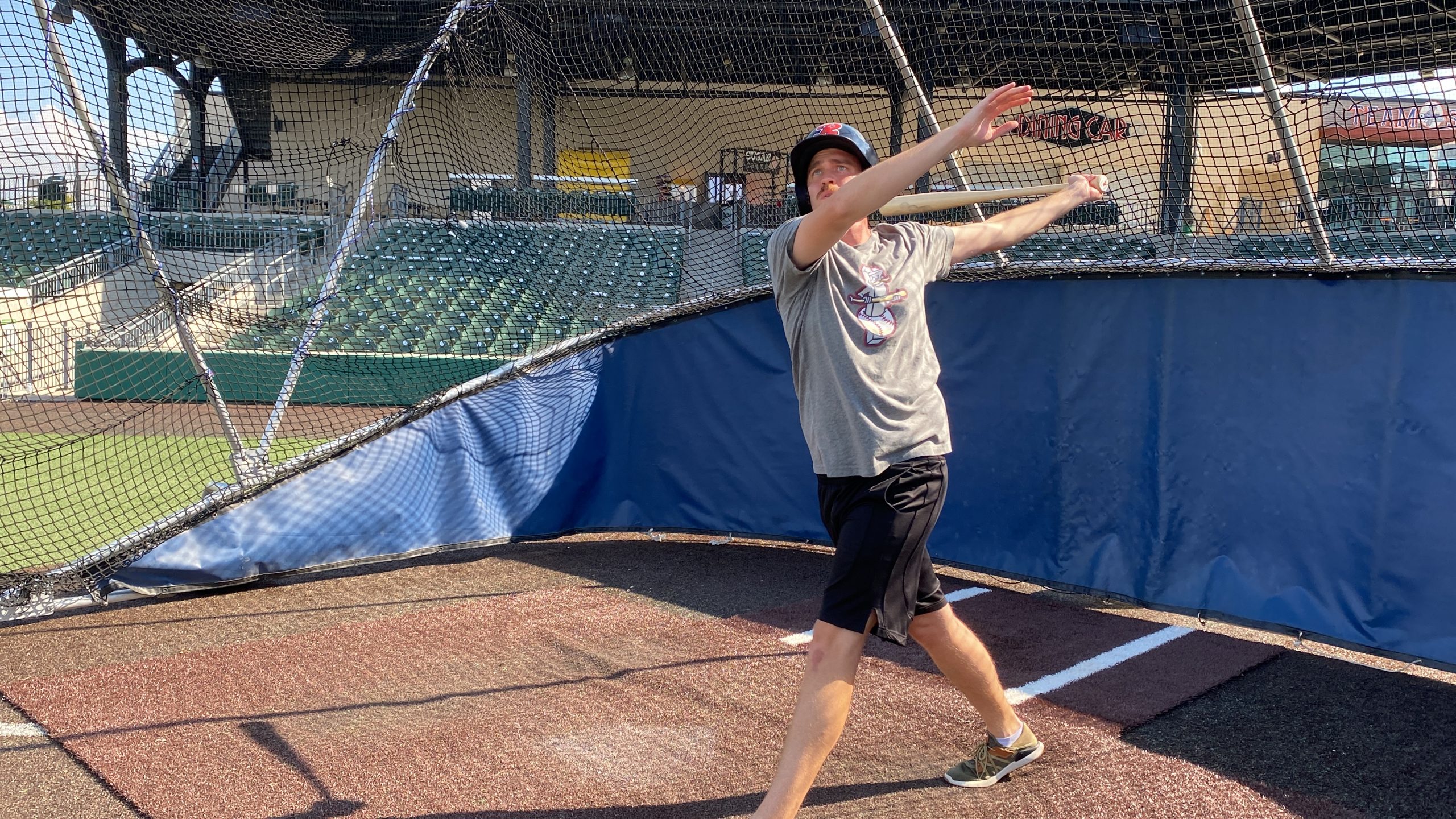

With my new red Railroaders cap on and a wooden bat the team gave me, I headed down to the field to try out my first gameday task: batting practice. I put on my second hat of the day, a Railroaders helmet, and stepped into the batter’s box. A coach from the Railroaders’ opponent, the Kane County (Illinois) Cougars, agreed to throw me a few rounds. Though I played my whole life, I hadn’t hit a baseball in 13 years. After a couple of pop-ups, I started to get nervous that I didn’t have it in me anymore. The Kane County players were milling around the cage, stretching, and getting ready to take some hacks of their own.

On my third swing I hit a solid grounder out to shortstop. That’s when I really started to get a feel for it and began roping some line drives to the outfield. I even hit two balls to the warning track that bounced into the fence, to the surprised cheers of the Kane County coaches and players. With my hands rattling from the wooden bat and all the muscles in my back and torso screaming at me, I bowed out, happy to have succeeded in my first task. I grabbed my glove, put my Railroaders cap back on, and jogged out to the outfield to shag some fly balls while the Kane County players hit. Their power far exceeded mine, as they began blasting prodigious home runs to all fields.

Born To Do It

Though most of these guys could only dream of being major leaguers, they are still incredible ballplayers. Many of them spent years in the minor league systems of MLB teams and found themselves playing in independent ball after being released by those teams. Playing in the American Association, and other independent leagues like the Pioneer, Frontier, and Atlantic, often is seen as a final shot at achieving their dreams. There are also international leagues that might provide a higher-paying opportunity. In fact, a Railroaders player bolted midseason to play for a bigger payday in the Mexican League.

The rosters of these teams are in a constant state of rotation. If a player is doing great, he might get that dream phone call from an MLB team adding him to their minor league system, or if a player is struggling, he might decide it’s the end of the line for him and retire. The pay isn’t great, and the schedule is brutal. American Association teams play 100 games, 50 at home and 50 on the road. A 30-hour bus trip from Cleburne to Winnipeg might be the final straw that shows a player that his time in baseball has run out.

That’s exactly how right-handed pitcher Michael Krauza felt in 2021. The Pittsburgh native had been cut twice from his high school team but afterward bounced around playing club baseball, American Legion, and at two colleges before finding something special with his slider while playing at Division II Mercyhurst in Erie, Pa. After going undrafted he gave baseball one last shot by signing with the Houston Apollos of the American Association in 2021.

There was one problem with the Houston Apollos: They didn’t play in Houston. They were an all-road team created last season. After one week of living that life, Krauza was done. He had survived so much in his career and had gone further than anyone ever thought. It wasn’t worth it to keep going. When the Railroaders heard he had quit, they begged him to come sign with them. It took some convincing, but he agreed to give it one last shot.

In Cleburne, Krauza (pictured) found a second home. Players stay with host families during the season, and Krauza says he and his host family grew so close he feels like a permanent member of their family now. His results on the field were staggering, enough so that by midseason in 2022 the New York Mets purchased his contract. The kid who was twice cut in high school and who quit baseball in 2021 was headed to affiliated ball to try and achieve his dreams. His story is exactly why these players keep hanging on. In baseball, there’s always a chance.

“God wanted me in Cleburne for a good reason,” Krauza told me. “That’s where I was supposed to be.”

As much as the results on the field matter to the players like Krauza, independent league baseball is as much about keeping the fans entertained as it is winning. The next hat I had to put on was big, yellow, and extremely uncomfortable.

I was going to be the mascot, which for the Railroaders is either Spike, an anthropomorphic railroad spike, or Gandy, an old man railroad worker. When I arrived in the mascot locker room, I was informed that I would be neither one. Instead, I would be Elbow the Noodles, the giant blow-up costume that is a bag of La Moderna noodles, the sponsor of Friday night’s fireworks.

“I’m so glad you’re here, I hate being the noodles,” Diesel Davis, a 16-year-old intern, tells me. “It’s so small and hot and the kids always want to hug you and punch you and try to make you fall over.”

When the time came to head to the field, it quickly became apparent that Davis was right. I’m 6 feet 4 inches tall, and the costume was clearly made for a person about 5 feet 9. When I stood up, the eyes were at chest level. This meant I had to hunch over to see. And the costume was so wide that I had to walk sideways down the aisle to get to the field. Once on the field, though, I had a great, if extremely hot and uncomfortable time, interacting with fans and the little league team being honored on the field. It is scientifically impossible not to crack a smile when you see a giant bag of noodles with eyes and hands, so the fans loved me.

After 30 minutes it was game time and we headed back to the locker room. I unzipped the costume and nearly collapsed from the heat. My mascot duties were done for the day, but Jalynn Groseclose, 17, and Landen Ince, 16, who were playing the other mascots had to head back out after a break to entertain fans the rest of the game. Between innings the Railroaders put on competitions, dances, and giveaways to keep the fans smiling no matter what is going on in the game.

Later I walked up to the Railroaders radio booth. The game was being called by college interns Briggs Loveland and Seth Dowdle. The final hat I put on was the radio headset to spend an inning with Dowdle on the radio broadcast. The game Dowdle and Loveland were calling was a big win for the Railroaders, but truthfully, most fans were staying until the end of the game for the postgame festivities. Kids poured onto the field to run the bases, as players and their families milled about waiting for the fireworks to start. I was about to head out when something caught my eye. Elbow the Noodles had reappeared on the field, but I had seen Groseclose and Ince leave already. That meant that Davis had to squeeze into that noodle costume after all.

As I walked out of the ballpark on a warm August night in my Railroaders hat, I thought about those kids assaulting that giant noodle costume and a big smile crept across my face. ⚾️

The American Association

The American Association is an independent, unaffiliated minor league that started in 1903 separate from the more prominent American and National Leagues that would form what we now know as Major League Baseball. That league folded twice in the ensuing 100-plus years and restarted again in 2005.

The American Association teams are spread throughout the Midwest and West and Canada:

West Division

Sioux Falls (South Dakota) Canaries

East Division

Kane County (Illinois) Cougars

Lake Country (Wisconsin) DockHounds

Find out more at aabaseball.com.

Photography courtesy of Scott Bedgood and the Cleburne Railroaders.