Rodeo bullfigher Roach Hedeman looks back on decades of protecting riders, entertaining crowds, and cheating death as a rodeo clown.

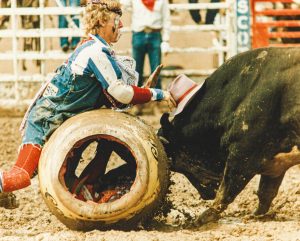

At a small rodeo on the outskirts of Wichita Falls, Gary “Roach” Hedeman stares at an empty red-dirt arena, recalling the time Panhandle Slim, a legendary bucking bull, stepped on his head. Oh hell, this is going to hurt, he recalls thinking.

“That sonofabitch used to run over me all the time,” Hedeman says. “He didn’t break anything. I got lucky. He usually turned back and spun closer to the pens, but he went farther. My timing was off.”

Nowadays, Roach, 61, spends his time judging small bull-riding competitions around Texas instead of fighting bulls as a rodeo clown. He’s also been hosting auctions and benefit shows for rodeo friends who are all older and facing health issues. The rodeo life isn’t known for its good retirement and health insurance packages. Roach has had to work several odd jobs to make ends meet, and when he was married, rely on his wife, who worked for a school district, to provide health insurance.

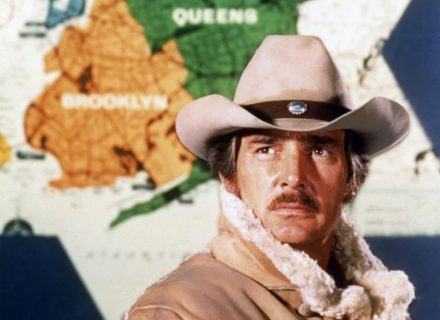

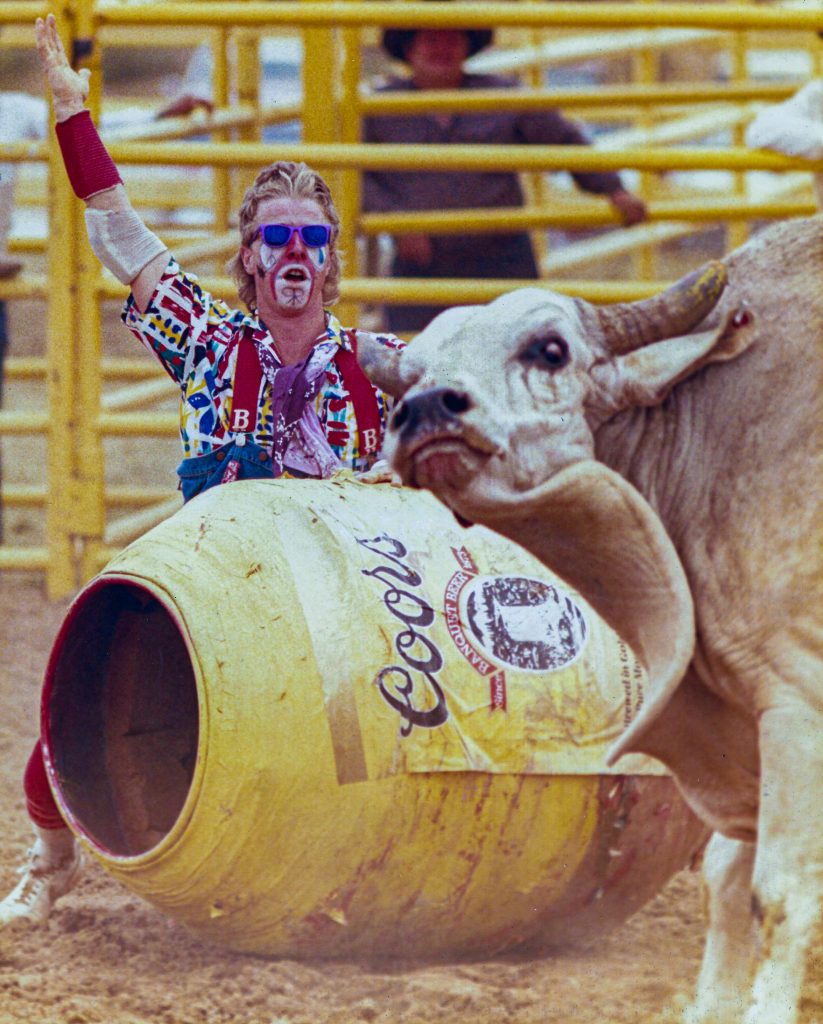

It’s a warm September evening in 2021, and the retired rodeo clown seems larger than life walking among the bull pens, bull riders, and stock contractors behind the rodeo arena. He moves slower than he did when he was younger in cleats, elbow, knee and hip pads (for when he was sore), and tape for his ankles. White paint around his eyes and mouth, red paint on his nose, he wore a black peace sign under his right eye, a blue teardrop under his left one, and double Rs on his chin for him and a childhood friend who accidentally shot and killed himself when they were younger. But he quit wearing the makeup in the late ’90s.

“They weren’t called bullfighters back then,” he says.

Roach wears his rodeo clown scars proudly, including a burn scar that covers the left side of his body from the belly up. He got it from the malfunction of a gunpowder trick that also blew off his thumb. He greets the cowboys and cowgirls with a nod and a smile.

“This motherf’er is the best bullfighting, bull-riding motherf’er I’d ever seen,” one announces as we walk past.

“OK, OK, I’ll give you your $5 later,” Roach tells him and laughs.

Their admiration, in part, has to do with Roach’s legacy. Along with his involvement in the New Mexico Junior Rodeo Association, the National High School Rodeo Association, National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association, and Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association, he fought bucking bulls at more than 400 rodeos, including the 1996 National Finals Rodeo and the Professional Bull Riders world finals between 1996 and 1999. He also raised Biloxi Blues, the 2006 World Champion bucking bull, and was inducted into the Texas Rodeo Hall of Fame in 2014.

“I think everyone else was sick that year,” he jokes.

For several decades, he entertained fans with Buster the Beach Dog and Trigger, a palomino pony he trained to count, play dead, and say prayers.

They’re dead now. Roach smiles when he mentions their names.

Only about a dozen of the 27 bull riders expected on this early September evening have shown up to ride for the $4,000 purse. It would have been a larger amount, Roach says, if more riders had paid the entry fee.

Roach’s eyes lose focus, and he pushes back his cowboy hat and shakes his head. “It’s not like it used to be. When we were young and getting on bulls, there would have been 59 guys standing here, wanting to get on the bulls. We would have been turning them down, not having enough bulls for them to ride.

“I’ve been saying it for 25 years now: rodeo and bull riding is slowly dying.”

Roach gravitated toward the rodeo clowns in the 1960s when he was a child in northeastern New Mexico and El Paso. He earned his nickname at 4 years old from a family friend who told Roach’s father, “That boy gets into everything. He’s just like a cockroach.”

He began hanging out with the rodeo clowns, who, in turn, would let him help them with their clown acts. His father, Red Hedeman, worked at a racetrack in New Mexico in the summer and in El Paso in the winter. Roach’s youngest brother, Tuff, was the only one of the seven siblings born in the Lone Star State. “I used to tell him as a little kid, ‘They just found you. You’re adopted. They found you down on the plaza,’” Roach recalls behind the bull pens at the Wichita Falls rodeo.

As a kid, Roach rode steers just like every other ranch kid, roped calves, and ran barrels. He credits professional bull rider Cody Lambert’s father, Cliff Lambert, and a bunch of other racetrackers for building an arena on the outskirts of El Paso where they would play and practice all day long. “I think Tuff was like 4 when he rode his first calf,” he says. “He was so scared, but he didn’t let go until the very end and won it. Everybody thought he was … Well, he ended up being what they thought he was.”

Tuff became a world champion bull rider, the former president of the Professional Bull Riders Association, and a member of the Pro Rodeo Cowboy Hall of Fame. Today, he runs Tuff Hedeman Bull Riding Tour, which offers action-packed bull riding at rodeo arenas around the country.

It all started at that arena in El Paso.

“When we started really moving up and practicing, we didn’t really have anyone to be the bullfighter while we practiced,” Roach says. “I just started doing it.”

Roach’s friend Roger Faubion had been bullfighting at high school and junior rodeo competitions in the 1970s. Roach, who was 15 then, started helping him. He’d ride his 8-second ride as a bull rider, get off, and then, in his boots and spurs, work as a rodeo clown, earning, he says, an extra $35 for doing it.

He eventually got letters of recommendations from a couple of rodeo clowns and a stock owner so he could become a rodeo bullfighter apprentice in the PRCA. As an apprentice, he worked five rodeos in a year before he received his PRCA card.

As for training, an old rodeo bullfighter, Jimmy Anderson, once told him, “If his head’s cocked to the left, you go to the left. If his head’s cocked to the right, you go to the right.”

“That was it,” Roach says. “That was about all the instructions I got.”

Roach held the suitcase bomb in his lap at a rodeo arena in Utopia, a small South Texas town with a post office, a fire station, and a general store. An early morning in 1985, he was hoping that his cleaning hat trick worked better than it did the night before when it blew smoke like a dud firecracker instead of exploding the cowboy hat. The general store owner came up to him after the first night of the rodeo and said, “Is it supposed to go like that?”

“No, it was supposed to blow up the hat,” Roach said.

“Your gunpowder is old,” replied the store owner. “Come down to the store, and I can fix you up.” He offered everything from ham to black powder at his store back then, Roach says.

The next morning, Roach decided to do a few practice runs to make sure his hat trick worked. Basically, how it works, he says, is he’d have a bicycle pump with a long air hose on it with a balloon attached to a small pipe at the end. He’d go up to a cowboy and ask him if he could clean his hat for free and then pump up the balloon and put the cowboy hat on it. He’d tell the crowd, “One more puff of air to clean the hat” and push a button that would ignite the gunpowder and cause the hat to explode and the cowboy to chase Roach around the arena.

Quail Dobbs, a legendary Texas rodeo clown, taught him the trick. “He took me under his wing,” Roach says. “He didn’t measure the gunpowder. He’d just pour it from a little bag, and he’d say, ‘I like a big boom’ and pour a little more powder and then a little more.”

In the 1980s, Roach worked for Bad Company Rodeo, an award-winning stock company that his friend and former roommate Mack Altizer, another inductee of the Texas Rodeo Hall of Fame, had founded in the early ’80s. He created what would become the model for entertaining fans at the rodeo, using pyrotechnics and rock ’n’ roll. “We’re like brothers,” Roach says. “We grew up and went through junior rodeo together in college. … He’s a great all-around cowboy.”

Roach started doing the cleaning hat trick to earn a few extra bucks. At the time, he was only clearing between $150 and $250 per performance, but a specialty act increased the amount, depending on its popularity. Another rodeo clown helped him make the suitcase bomb at the Utopia rodeo arena. The first two attempts, Roach says, the trick worked perfectly. On the third attempt, when he reached over to grab the suitcase to put it in his lap it exploded.

“I was at the point of crying,” says Altizer, who was the stock contractor at the Utopia rodeo. “We all got lucky on that one. We were only about 30 miles from the burn center in Kerrville. If that had happened a million other places, he wouldn’t have …”

At the rodeo in Wichita Falls, Roach shakes his head recalling the tragedy more than 30 years later. A reminder of the incident scars the left side of his body. “If I had been sitting above it,” he says, “I wouldn’t be here.”

It wasn't his first or last time to escape death in the rodeo arena.

After he retired in the early 2000s, Roach never left the arena. He’s still helping young bull riders pursue their championship dreams, and one of them approaches him behind the chutes at the Wichita Falls rodeo in September. The young man is wiry like Lane Frost, with dark hair and an aw-shucks demeanor. He looks nervous approaching one of his legends and, no doubt, taps into the courage he has on reserve for his bull ride later this evening.

“What’s up, Brother?” Roach says. “You doing good? You riding?”

“Yeah, well, I’ve got to find 40 more dollars so I can enter,” the bull rider says.

Roach opens his wallet and gives him a $50 bill.

Opening his wallet, the bull rider grabs some cash to give Roach and notices him shaking his head. “That’s just your change,” says Roach.

“No, you keep it. You might need a soda or something.”

The bull rider doesn’t know what to say.

Roach smiles at him. “Go on, go on — you’ll get me back later.”

Nodding, the bull rider rushes off to pay his entry fee for the ride.

He doesn’t stay on the bull, though. Not many do anymore, not since bull breeders began using science to breed and clone bulls from championship bloodlines in the late ’90s and early 2000s and training them to become champion bulls from an early age. Only 25 percent stayed on in 2021 compared with 38 percent in 2001, according to ProBullStats.com.

“Back in the day, you might see three or four great bulls out of 12 or 15, and the rest were mediocre,” Roach says. “Now there are lots of them.”

It wasn’t a bullfighter injury that ended Roach’s career. Instead, he was out riding horses with his daughter in 2000 when his horse got spooked and threw him. He’s got a 6-inch metal plate attached to his pelvis to show for it.

A few months after the Wichita Falls rodeo, Roach calls and says he’s starting the Hedeman Rodeo Memorabilia Sales and Auction to raise money for organizations such as the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame and the Justin Cowboy Crisis Fund. It’s just another way he’s trying to help bull riders and bullfighters. He was calling from New Mexico, where he was burying another old bullfighter friend. He reminisces about his days with Tuff, Cody, Lane, and Mack, opening up in a way that’s rare for cowboys.

Roach is in a melancholy mood, and though he worries that rodeo might be dying, a quick Google search reveals it’s actually thriving, if far different from the way it was in his heyday. Today, it’s more like the NFL with millions attending events and rodeo athletes, in full protective gear, pulling down some big bucks in earnings due, in part, to Tuff, Cody, Mack, and Roach.

It’s enough to make an old bullfighter wistful.

“We were like the cowboy rock stars,” he says before hanging up. “We worked all day and rodeoed all night.”

Photography: (All images) Dave Jennings

From our July 2022 issue