From "Colter's Hell" to Theodore Roosevelt's "veritable wonderland" — the evolution of Yellowstone from primordial playground to first national park.

Yellowstone celebrates its 150th anniversary as a national park this year. That is big news indeed, and worthy of big celebration. It is, after all, the country’s first national park and one of the crown jewels of the entire system.

But the human history of this geologically stunning and beautiful landscape in the heart of North America’s West is but a blip in a story that reaches back millennia. Yellowstone has seen human habitation for more than 11,000 years—not that human habitation defines the place. The very geology of the place seems to point a primordial finger into deep prehistory.

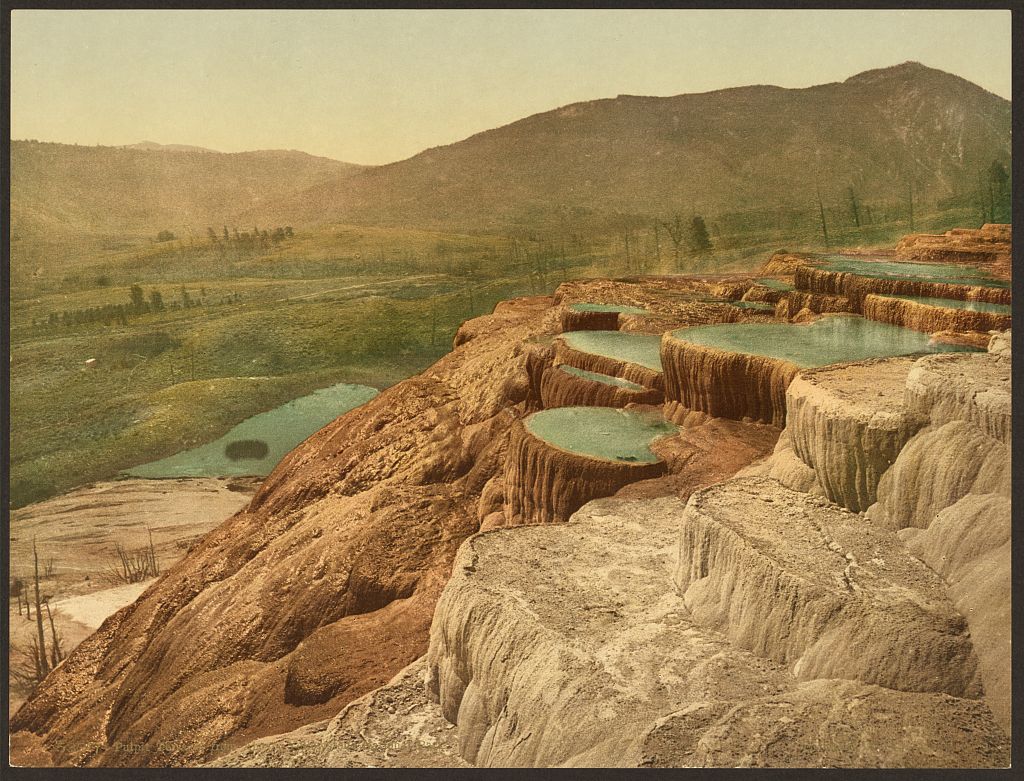

It is a region of remarkable geothermic activity, replete with hot springs, geysers, bubbling mud pots, and fumaroles. Penetrated by four mountain ranges—Gallatin, Washburn, Red, and Absaroka—it has an abundance of deep glacier-carved valleys, tumbling rivers, deep lakes, eroded basaltic lava flows, fossilized forests, and black obsidian. It is a cornucopia of strange and beautiful features of Mother Nature.

Castle Geyser, Yellowstone National Park, ca. 1898.

Castle Geyser, Yellowstone National Park, ca. 1898.

Nearby one will find the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. Called “Mi tsi a-da-zi” (Yellow Rock River) by the Hidatsa, it was likely this river that brought the first humans here. In addition to the Hidatsa, this otherworldly place has played host to the Crow, Shoshone, Kiowa, Blackfeet, Bannock, Nez Perce, and nearly two dozen other tribes. All were drawn to the area by its natural abundance: bison, grizzly bears, elk, bighorn sheep, deer, rabbits, and edible vegetation all set in a location of splendor with cascades of fresh, flowing water and cliffs of obsidian that could be knapped into spearpoints and arrowheads. Some of the oldest are the Clovis points used in pursuit of the now-long-extinct mammoth and mastodon. Archaeological activity in Yellowstone has revealed more than 1,850 sites of human habitation dating back thousands of years.

The white man is a relative newcomer to this primeval wonderland. Likely the first to set foot here was one John Colter, a member of Lewis and Clark’s expedition to the West Coast from 1803 to 1806. When Colter obtained his discharge from the expedition in 1806, he remained in the West pursuing opportunities as a fur trapper. One of his journeys brought Colter into what is now Yellowstone, where he spent the winter of 1807–1808. On his return to the East, his accounts of Yellowstone, with its warm springs, geysers, mud caldera, and steaming rivers, were received with skepticism as listeners scoffed at “Colter’s Hell.” Subsequent trappers in the early part of the 19th century—including Daniel Potts, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Osborne Russell, and Jim Bridger—described the wonders of the region. The latter’s reputation as a notorious spinner of tall tales once again relegated his accounts of Yellowstone to the status of far-flung rants of fiction.

One listener, however, Warren Angus Ferris, a clerk for the American Fur Company, was intrigued by these stories and set off on his own to visit the region with Native Americans hired to guide him. He went so far as to draw a map of the area and was the first to use the term geyser to describe the geothermal wonders of Yellowstone. While he kept copious notes of his venture, his observations did not appear in print until 1843–1844 in serial form in The Western Literary Messenger. Whatever else Ferris did with his notes remains as nebulous and ephemeral as the mists above Yellowstone’s thermal pools and mud pots. As far as we know, his completed reminiscences did not appear in book form until 1940, when Ferris’ book was published as Life in the Rocky Mountains 1830–1835. But it was not until spring of 1859 that the Army’s Corps of Topographical Engineers dispatched Capt. W.F. Raynolds to do a more complete survey. Accompanying Raynolds’ party was geologist Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden with the redoubtable Jim Bridger as guide, the latter believed to have spent time in the area. Despite their best efforts, heavy snowfall frustrated their undertaking, and it would not be for another 10 years that Yellowstone was explored in detail, this time by a group of curious Montana citizens. Their observations sufficed to stimulate more interest, and they were soon followed by a more successful survey in 1870 sponsored by Henry David Washburn, the surveyor general of Montana Territory.

The Washburn Expedition succeeded in rekindling national interest in Yellowstone with the federal government organizing a subsequent effort, this time headed by Dr. Hayden. Hayden received his instructions directly from the secretary of the interior specifying, “… the object of the expedition is to secure as much information as possible, both scientific and practical, you will give your attention to the geological, mineralogical, zoological, botanical, and agricultural resources of the country. You will collect as ample material as possible for the illustration of your final reports, such as sketches, sections, photographs, etc.” This expedition was to be somewhat larger and more intense, accompanied by an Army topographical survey team headed by Capt. John Barlow.

As Hayden was assembling his team in Ogden, Utah, he received a letter from Barlow, the chief engineer of the Army’s department of the Missouri stating, “Gen’l Sheridan desires me to join your party previous to its entering the ‘Great Basin’ of the Yellow Stone lake—and I am greatly delighted at the prospect of seeing the wonders of that region under such favorable auspices.” He went on to note, “I had determined some time ago to endeavor to make an excursion into that country this summer taking a small party along, but as you are to make such a thoroughly exhaustive examination there will probably be no occasion for undergoing the expense of a second expedition of like magnitude.”

It was a tall order for Dr. Hayden, with a detailed report due to Congress and the Smithsonian Institution expected no later than January 1872, so he manned his expedition with an abundance of specialists: botanists, topographers, geologists, naturalists, zoologists, physicians, mineralogists, entomologists, agricultural specialists, and even photographers and artists. Capt. Barlow’s party joined up with Hayden’s at Fort Ellis near Bozeman, Montana, and the expedition proceeded through what is now the north entrance to the park. The joint effort was escorted and protected by Troop F of the 2nd U.S. Cavalry. The resulting exploration of Yellowstone, which lasted from late July through the end of August, was superb, as Hayden was able to note in a letter written in August of 1871: “[N]o portion of the West has been more carefully surveyed than the Yellow Stone basin.”

But all was not serene, for the exhaustive efforts of Capt. Barlow’s survey were all lost in October 1871. He had returned to the headquarters of the Military Division of the Missouri in Chicago to prepare his reports when the great Chicago fire broke out. As he wrote despairingly to Hayden, “All my instruments, maps, books, and everything brought back from the Yellowstone, including specimens were consumed. I have had to begin all anew.” Barlow had managed to save only 16 photographic views of the area. Luckily, he had also been able to salvage his journal of the expedition and with the assistance of Hayden, who was able to provide him with 100 photographic prints and stereographic views, he was able to complete his report to Gen. Sheridan.

The public reaction to the expedition was almost immediate with the September 18, 1871, issue of The New York Times, crowing, “There is something romantic in the thought that, in spite of the restless activity of our people, and the almost fabulous rapidity of their increase, vast tracts of the national domain yet remain unexplored. As little is known of these regions as of the topography of the sources of the Nile or the interior of Australia. They are enveloped in a certain mystery, and their attractions to the adventurous are constantly enhanced by remarkable discoveries. … Sometimes, as in the case of the Yellowstone Valley, the natural phenomena are so unusual, so startlingly different from any known elsewhere, that the interest and curiosity excited are not less universal and decided.” Therefore, it was not surprising when on December 4, 1871, the 42nd Congress of the United States of America passed an act that “dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” President Ulysses Grant signed the act into law on March 1, 1872.

Yellowstone had become the nation’s first national park.

Why Is It Called “Yellowstone”?

“Contrary to popular belief, Yellowstone was not named for the abundant rhyolite lavas in the Grand Canyon of Yellowstone that have been chemically altered by reactions with steam and hot water to create vivid yellow and pink colors. Instead, the name was attributed as early as 1805 to Native Americans who were referring to yellow sandstones along the banks of the Yellowstone River in eastern Montana, several hundred miles downstream and northeast of the Park.” (USGS.gov)

Once Yellowstone was established as the first national park, it wasn’t long before its wonders began to attract tourists. They traveled by rail to Livingston, Montana, and then on to the park via stagecoach, horseback, or wagon. At first visitors were rare due to the difficulties in getting to the region, but still they came.

In August of 1877, several small parties were enjoying their park sojourn when they were interrupted by a contemporary crisis. The Nez Perce Indians had been displaced from their traditional homes in Oregon and were in flight from pursuing soldiers. Having fought their way through Idaho, a group of Nez Perce numbering 250 warriors and about 500 women and children entered Yellowstone hoping to pass through to link up with the Crow tribe in Montana.

No sooner had they entered the park than they encountered a party of tourists from Radersburg, Montana. It was a tense meeting with the warriors forcing members of the party to feed them. The Radersburg party complied, doubtless mindful of the Seventh Cavalry’s disastrous experience the year before on the Little Bighorn. The Radersburg party was relatively fortunate. While two of the men were shot and badly wounded, the rest of the group escaped or were eventually released unharmed. Other parties in the park were not as lucky. A number of men, mostly prospectors, were killed in encounters with the fleeing Indians.

The Nez Perce did not linger but pressed on as rapidly as they could with Gen. O.O. Howard and some 2,000 soldiers in hot pursuit. Rebuffed by the Crow, the Nez Perce fled north hoping to find refuge with Sitting Bull’s Lakota in Canada. It was a forlorn effort brought to a halt just 40 miles short of the U.S.-Canadian border, where Col. Nelson Miles took the surrender of Chief Joseph on October 5, 1877. This was not the only encounter with Native Americans in Yellowstone. The following year, a group of Bannock warriors fled Idaho passing through the park. But once again, Col. Miles pursued and halted their progress within 20 miles of what is today known as Dead Indian Pass.

Despite the harrowing experiences of the Nez Perce and Bannock crossings, the reputation and allure of Yellowstone continued to grow as word of the park’s natural attractions spread nationwide. As visitors flooded in, the park’s management began to have concerns about the safety and behavior of their guests. In response, the U.S. government in 1886 dispatched Company M of the 1st U.S. Cavalry to assist in park management. It was an interesting and challenging assignment as the troopers guarded the major attractions, evicted troublemakers, arrested poachers, discouraged vandalism and souvenir hunting, and patrolled miles of trails either on horseback or on skis.

It would be five years before the government realized that this would be a prolonged mission and appropriated funding to construct more permanent facilities beyond the simple frame housing for the troops. The first substantial buildings of the resultant Fort Yellowstone were completed by 1891, most of which remain to this day. The Army would continue to have a commanding presence in Yellowstone until 1918, when its duties were finally ceded to the National Park Service, which had been established two years earlier.

An early visitor to the park was a young Theodore Roosevelt, who, taking a much-needed break from New York politics, brought his family to Yellowstone in 1890. An avid outdoorsman, he loved being back in an environment similar to that in which he’d spent several years as a cowboy in the Dakotas, and it wouldn’t be his last visit. He would return in April of 1903, this time as president of the United States.

On this presidential trip, Roosevelt was accompanied by his close friend and mentor famed naturalist John Burroughs, whom he would refer to as “Oom John” (Dutch for Uncle John). Despite an entourage that naturally included staff and Secret Service officers, Roosevelt managed to spend a large part of this two-week sojourn in the wilderness he loved. As Burroughs would later write, “The President wanted all the freedom and solitude possible while in the Park, so all newspaper men and other strangers were excluded. Even the secret service men and his physician and private secretaries were left at Gardiner. He craved once more to be alone with nature; he was evidently hungry for the wild and the aboriginal,—a hunger that seems to come upon him regularly at least once a year, and drives him forth on his hunting trip for big game in the West.”

Roosevelt was captivated by the park. “The geysers, the extraordinary hot springs, the lakes, the mountains, the canyons, and cataracts unite to make this region something not wholly to be paralleled elsewhere on the globe,” he said in a speech delivered at Yellowstone.

However attractive Yellowstone was to the general public, it remained challenging to get there. Finally, in late 1907, the Union Pacific Railroad completed a spur line to the park’s west entrance, and, by 1915 automobiles were afforded access. More and more facilities for visitors were constructed within the park, and attendance figures grew exponentially. By 1940 over half a million people visited annually. Still Yellowstone’s attractiveness and popularity grew to the point where by 2016 more than 4 million visitors flocked to the park annually. During the pandemic, visitation hit 4.9 million in 2021, nearly a million more than in 2020. In this, its sesquicentennial year, park attendance is estimated to surpass 5 million.

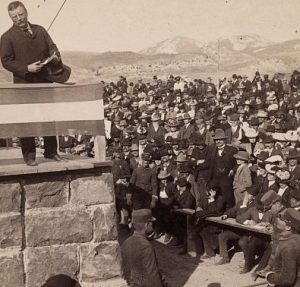

This is not to be wondered at, considering the natural beauty available to those who venture there to see what was probably best described by President Theodore Roosevelt in a speech in 1903: “The Yellowstone Park is something absolutely unique in this world, so far as I know,” he proclaimed on the occasion of the laying of the cornerstone of the arch at the north entrance of the park. The entire town of Gardiner had shown up for the event and heard him declare, “Nowhere else in any civilized country is there to be found such a tract of veritable wonderland made accessible to all visitors, ...”

And so it remains.

Yellowstone: One-Fifty

Kevin Costner will strengthen his Yellowstone connection later this year with a new project on the Fox Nation streaming platform. But it has little, if anything, to do with Costner’s hit Paramount Network drama and everything to do with the iconic national park. In the upcoming limited series Yellowstone: One-Fifty, the Oscar-winning actor will serve as host and narrator of four episodes exploring the history and wildlife of the Home of Old Faithful. Planned for release on the Fox Nation streaming service near the end of this 150th-anniversary year of the park, the commemorative series was co-developed by Costner’s Territory Films. Keep tabs on the release at foxnation.com.

Photography: Photocrom Co. & Detriot Photographic Co.

Images courtesy of Library of Congress Online Catalog, loc.gov.

From our July 2022 issue.