The first photographer to be invited into the Nez Percé’s inner circle since Edward S. Curtis, Texas-based Hunter Barnes pursued photography in the East but discovered the key to his camerawork among “The People” in the West.

In 1903, the already-legendary Chief Joseph was in Seattle to advocate for the Nez Percé, also known as Nimiipuu, or “The People.” A dodgy treaty with the U.S. government had hoodwinked the Nez Percé out of their ancestral homelands, and the weary warrior — after being forced to flee with his tribe and fighting on their behalf for so many years — was intent on fighting only to get his people back to the Wallowa Valley in Oregon. Also in Seattle on that day in 1903 was photographer Edward S. Curtis, who had not yet embarked on his ambitious life’s work, The North American Indian. Chief Joseph walked into Curtis’ studio, and, impressed by the famous warrior’s nobility and integrity, Curtis made a portrait of him that would become iconic. Through the fast friendship between the two, Curtis would come to regard Chief Joseph as “one of the greatest men who ever lived.”

More than 100 years later, photographer Hunter Barnes had his own intimate experiences and profound connections among the Nimiipuu. He grew up in the Outer Banks in North Carolina’s Hurricane Alley, geographically and culturally removed from the Pacific Northwest reservations where he would live for months at a time documenting the tribe. Going back and forth from his home in New York, he did two- and three-month stints at a studio he built in remote northeast Oregon. Barnes first gained their trust and friendship before he started taking photographs. In his hand-built studio adjacent the deepest river gorge in North America, he would end up putting in a half-year of eight-hour days in the darkroom hand-printing his photographs.

Barnes had arrived in the Pacific Northwest via New York City. In 2004, a friend suggested he visit the Tamkaliks Celebration Powwow in Wallowa, Oregon — the very ground of Chief Joseph and his Wallowa band — to see about the possibility of photographing the tribe. Over the next four years, Barnes would range from Oregon to Idaho to Washington, shooting more than a hundred rolls of film, capturing images of the Nimiipuu at powwows and at home on their reservations. While Curtis often lugged several still cameras in the field (he was said to favor the reversible-back 6½ x 8½-inch glass-plate Premo camera), Barnes shot with four cameras: a Mamiya C220, Pentax 67, Nikon FM2, and Polaroid 195 Land Camera.

The work would become the 2020 book The People, published by Reel Art Press.

“The People Collection was recently acquired by a private foundation,” Barnes says. “I had found a box of undeveloped film from the project and the foundation, after acquiring the collection, commissioned me to print those additional images. With the original 40 prints plus the rediscovered newly printed 16, they mounted an exhibition of 56 hand-printed silver gelatins.”

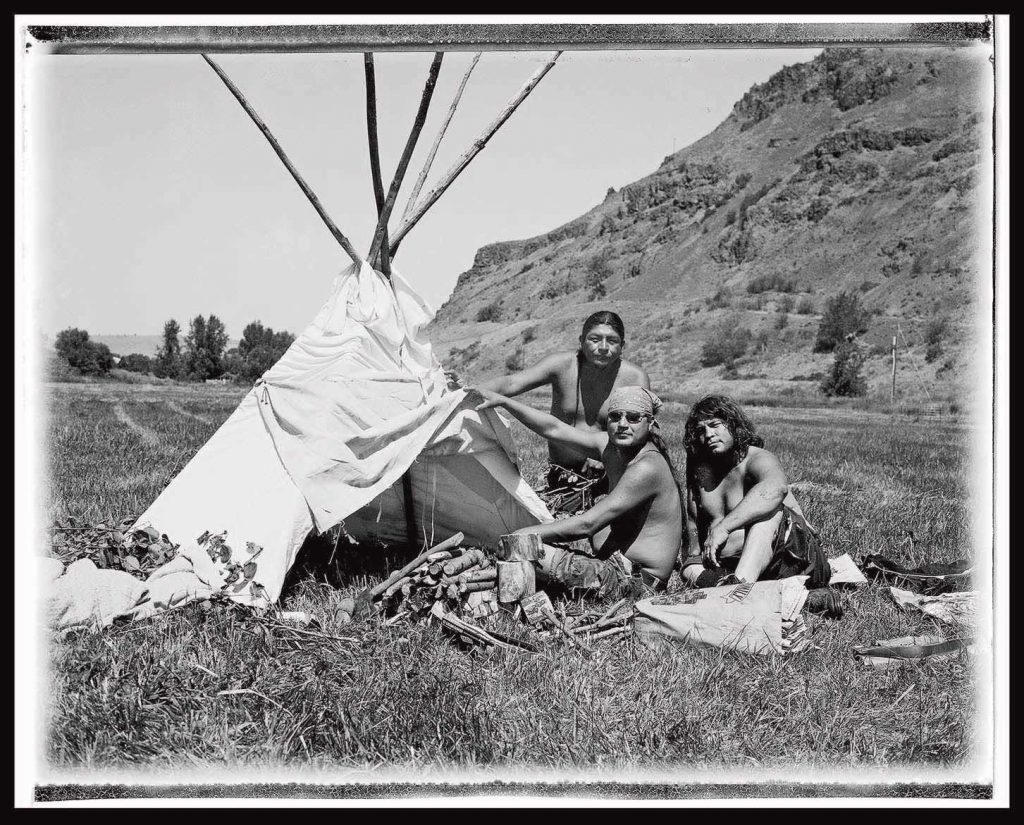

Smokehouse

Now based in Austin, Texas, Barnes is working on projects both close to home and far-flung, among them an untold story from an exhibition in Sri Lanka that he shot during the same time period he was working among the Nez Percé.

We talked to Barnes about his work and The People.

Cowboys & Indians: Your book The People also references Nimiipuu and Nez Percé Tribe on the cover, all referring to the same Indigenous group. Before we dive in, could you help us understand the different names and why it’s now important to you to refer to them as Nimiipuu almost exclusively?

Hunter Barnes: From my understanding, and what I heard from the tribe, is that when the French settlers arrived, they had the false assumption that all the Indigenous people had pierced noses. They referred to them as Nez Percé, which is French for “pierced nose.” The traditional name and spelling of the tribe is Nimiipuu, which translates “The People.” My intention in calling the book The People was to translate their proper name.

C&I: How did you get interested in the Nimiipuu?

Barnes: I moved to Wallowa County, Oregon, to do my first book, Redneck Roundup, which documented a dying breed of ranchers and the locals who live in that pocket of northeast Oregon. When it was done, a friend of mine who was an artist was working with the tribe on their powwow and I was invited. The idea of a project to document the tribe happened naturally. I had been told nobody had really gotten in there since Edward S. Curtis. I didn’t know who Curtis was at the time, and I didn’t know a thing about the tribe. I was introduced to one of the elders, Uncle Irving Waters; he was one of the nicest people I’d ever met. He and his family embraced me, and he became like family to me. I started out at a powwow over a weekend, camping out. They invited me to the rez and to sweat. I got my cameras, film, and some clothes. Some of the people didn’t have phones — I had their addresses and I just showed up at their home and started doing sweats.

C&I: That’s pretty special. …

Barnes: It hit me the magnitude of how sacred it was that I’d been invited to their homes on the rez and to the sweat lodge. I spent weeks just learning how to sweat, getting to know each other. We became good friends.

C&I: How did you segue to taking pictures?

Barnes: I explained my intentions were to take pictures. They wanted to teach me how to build sweat and learn their way of doing it. We got to know and like each other and began to trust each other. I was staying at my friends’ houses for weeks and months at a time. I needed the time to understand them, too. There’s a lot of responsibility in documenting somebody’s life. I spent lots of time just listening.

C&I: Talk to me about Edward S. Curtis’ work a century ago. The late Curtis expert Christopher Cardozo said we’d have no photographic record of those individuals had it not been for Curtis, and that covers whatever “sins” he might have committed in staging certain shots. How do you regard his legacy?

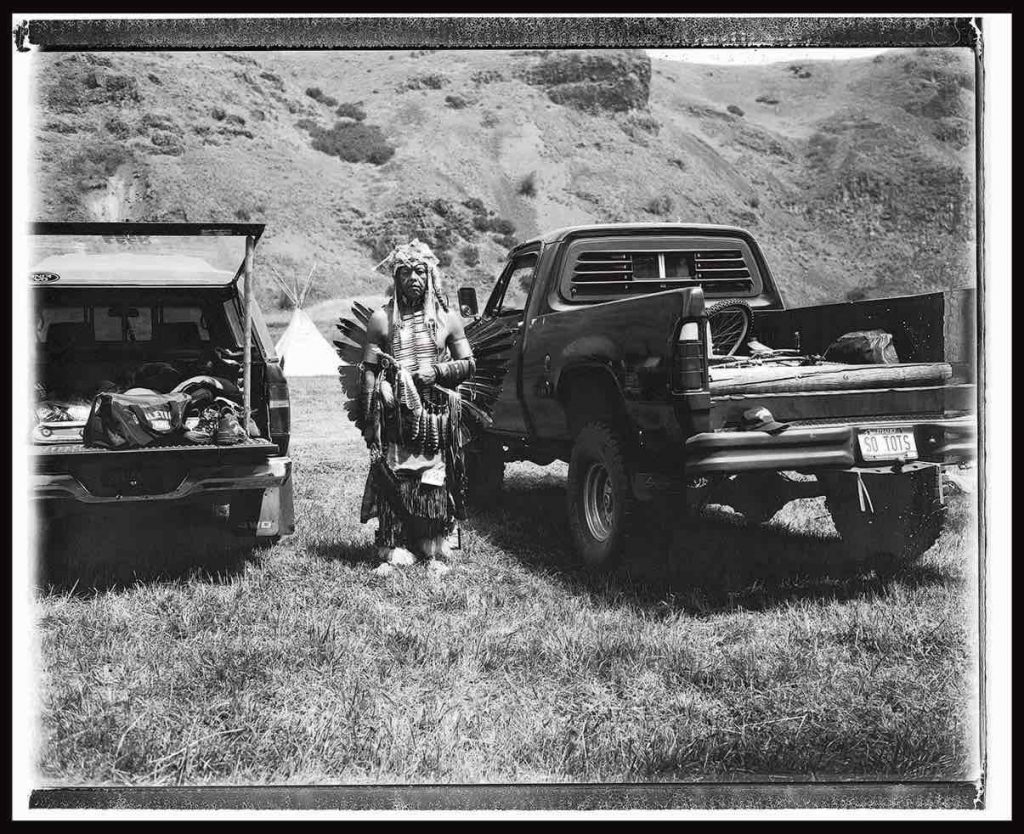

Barnes: That era was a time when you had to sit still. The shutters didn’t work as fast. Everyone kept telling me about Curtis. It wasn’t until I was editing the majority of the film around the end of the project that someone gave me one of his books. She pointed out certain pictures. “See this girl holding berries?” It was uncannily like my picture Play of a young girl holding berries. “Look at the fence and her jeans and her plastic bucket.” In the Curtis photo, the basket was woven and the clothes were buckskin, but the obvious similarities were plainly there to see. It was just a different time period.

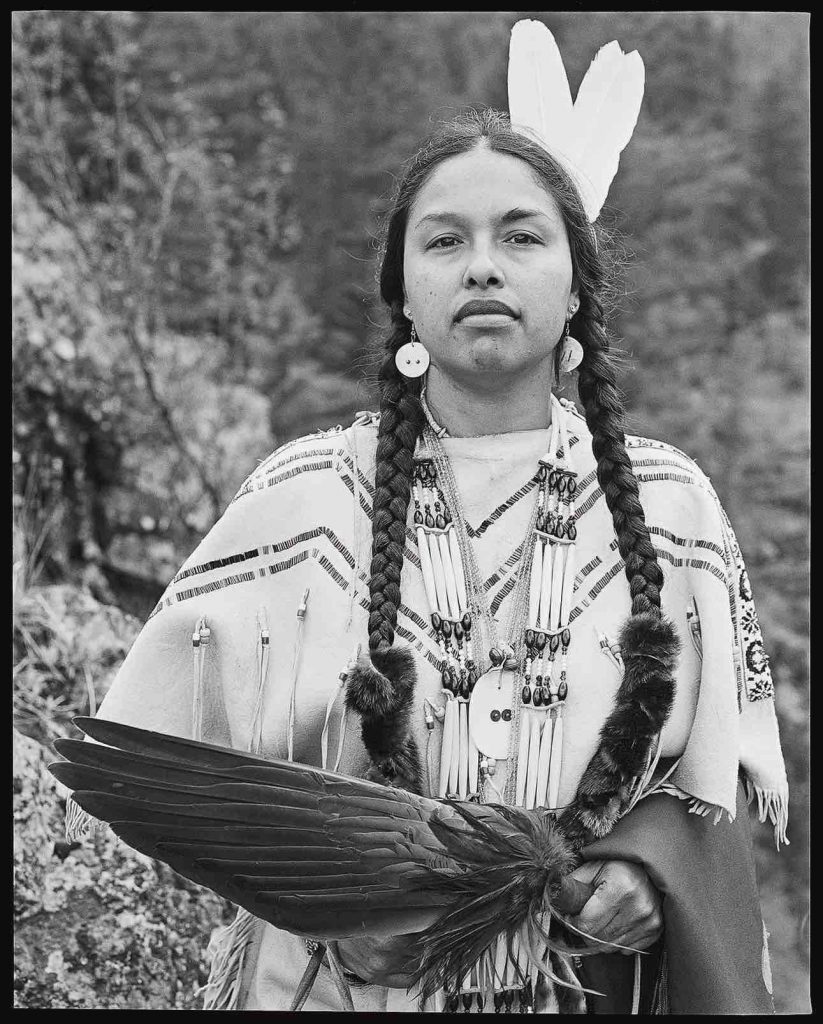

Cindy Wapato

C&I: Your photos grew out of your personal relationships.

Barnes: My pictures are of a very specific time and place. They’re a reflection of hanging out with people and getting to know each other, so they’re very organic — no staging or sets or anything.

C&I: Tell us about a specific shot that comes to mind.

Barnes: I have a picture of Cindy Wapato, a very good friend of mine. I’ve known her since Day 1. She’s the one who invited me to the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in Nespelem, Washington. In the book you’ll see a photograph of Cindy in her family regalia. I remember she carried this regalia in a suitcase. I can’t even tell you how many generations it went back. It’s the traditional dress. It’s what she wore. Years went by and I found some images I hadn’t noticed from the first round of editing. I decided to print one of the images for her. A couple of days later, she called me about this photograph. She told me something had happened to the family regalia — it was a devastating thing that there was no record of it. I told her, “Well you’ve got a record now.” There was something really beautiful about that to me. There’s something that was recorded that’s useful that you can carry on with your family.

C&I: How about another backstory about capturing culture for posterity, which is another thing Curtis was intent on.

Barnes: One of my favorite photos is one of Ann Samuels and her son, Tino. When I took it, she was the oldest living tribal member at the time. Her son was 72. I went to the rez in Lapwai, Idaho, with my friend Gaylen. I met Ann. She was there during the boarding-school era. She witnessed people having to get their braids cut. I sat in a La-Z-Boy recliner writing notes on napkins she gave me. She shared all these beautiful stories and wisdom. Taking her portrait documented history. She was the one; she held the key. So much history and language is being lost. She held all that knowledge.

C&I: You lived among The People off and on for four years over the span of this project. …

Barnes: I never expected it to take four years, but it was a process over time. I would leave my home and where I was working in New York City and head for the studio I’d built in Oregon. On the first trip, it was about a month before I really started taking photos at people’s homes. I’d go back and process film, edit, and make prints for everybody. The next trip out, I might stay longer, maybe the entire summer.

Nim

C&I: You actually also started a school, right?

Barnes:Yes, I started a photo program with Rose Charities at the Lapwai Boys & Girls Club, along with my great friend Mazdack Rassi at Milk Studios, who donated the computers for the kids to work on.

C&I: How have the images and the book been received by your Nez Percé friends?

Barnes: I donated a full edition of prints to the Nez Percé Tribal Council for their museum. I’m not sure what became of them. Some of the tribe have seen the book. I’ve also given prints to some friends I’ve stayed in touch with. A lot of my friends, the elders, have died — the virus is everywhere there. Gaylen’s wife, Mary, had just gotten the book after his death. She told me how much our friendship had meant to him, and I told her how much he meant to me. So much has come full circle and manifested from our visions we shared together.

C&I: These images are meaningful in so many ways, even life-changing for you because of the experience. Any parting thoughts about what you hope people will take away from the book and your Nez Percé photographs?

Barnes: There are several lines I wrote in the book that come to mind:

Four years shared with the people of the Nez Percé tribe.

Reflections of where I was invited, a vision of responsibility.

A spirit journey guided by a greater force, taught a new way to walk and breathe.

Visit Hunter Barnes online at hunterbarnes.com. The People, published by Reel Art Press (2020), is available on reelartpress.com. Barnes prints private commissions and selected images in very small limited editions; for information about prints, email [email protected]

From our January 2022 issue

Photography: (All images) courtesy Hunter Barnes