On the 150th anniversary of the birth of the great 20th-century photographer and ethnologist, and the landmark republication of his masterwork, we talk about the life and legacy of Edward S. Curtis with noted expert Christopher Cardozo.

The passing of every man and woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rights possessed by no other.” So said photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis, and he proved his conviction by devoting his life to creating a pioneering artistic ethnographic record of the North American Indian as a hedge against what he feared was their imminent demise.

In 1900 Curtis began a 30-year odyssey to photograph and document the lives and traditions of the Native peoples of North America. The New York Herald declared the monumental project “the most gigantic undertaking since the making of the King James edition of the Bible.” With The North American Indian, Curtis achieved the seemingly impossible: an extraordinary 20-volume, 20-portfolio set of handmade books composed of nearly 4,000 pages of text and more than 2,000 images presenting more than 80 of North America’s Native nations.

Christopher Cardozo, in turn, has devoted the last 45 years to preserving and disseminating Curtis’ work. Cardozo first discovered his work in 1973 and since then has authored nine books on the photographer, built the world’s largest collection of his work, and sent Curtis exhibitions to more than 40 countries. Cardozo is widely recognized as the leading authority on the body of work. This year he’s helping to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Curtis’ birth with exhibitions, symposiums, lectures, and other events across the United States. Nearly three years ago, he enlisted a large group of artisans to do a limited-edition artisanal re-creation of The North American Indian, Curtis’ magnum opus, which Cardozo expects to be completed in March.

C&I spoke with Cardozo about Curtis’ landmark achievement and why we’re still drawn to those “luminous, iconic, and profoundly revealing” photographs that continue to shape the way we see Native life and culture.

Cowboys & Indians: Curtis’ childhood didn’t provide an auspicious start, but it taught him to be self-reliant and persistent.

Christopher Cardozo: So true. He was born in 1868 and grew up in abject poverty in rural Wisconsin and Minnesota. His father was a poor itinerant preacher and the family was continually impoverished. Curtis was schooled only until the sixth grade. But he scraped together $1.25 to buy a lens and build his own camera when he was only 12. He loved photography, and by the time he was in his late teens he and his family had moved to rural Washington state. He soon mortgaged the family farm to buy a half interest in a photo studio in Seattle, which, as the gateway to the Yukon, was a boomtown. Within a few more years, Curtis had become sole owner of the most successful portrait studio in the Pacific Northwest.

C&I: Was there a particular event that set him on his path to “The North American Indian”?

Cardozo: In 1898 a number of luminaries from the East Coast establishment took a great interest in his early work. That led to an invitation to be the official photographer of a major scientific expedition to Alaska in 1899. This was a watershed experience for Curtis as he spent nearly three months with some of the greatest scientists, naturalists, and environmentalists in the world. Among them was George Bird Grinnell, who asked Curtis to accompany him the following summer to live among the Blackfeet and Piegan in Montana. There, during the summer of 1900, he was with Native people who were still following traditional ways. For the first time he heard personal stories, learned about sacred beliefs, and witnessed great ceremonies that were being outlawed by the U.S. government.

As a human being and as an artist, he was profoundly transformed by his experiences that summer. Because he was with Grinnell, who had lived with them for 20 seasons, he had unheard-of access to the most intimate and sacred details of their lives. In the five years he’d been photographing Native people prior to 1900, I believe he did it largely out of self-interest; he wanted to win photographic contests and gain national attention. But after his experiences with the Piegan and Blackfeet — and the Hopi — his motivation went from “How does this serve me?” to “How do I serve this cause of preserving a record of these amazing people and their culture?”

C&I: In response, he conceived his great project, “The North American Indian,” during that summer of 1900.

Cardozo: Yes — the experiences he had that summer in Montana among the Blackfeet and later in Arizona and New Mexico among the Hopi and Navajo crystallized his “big dream.” He realized Native culture was disappearing — possibly threatened with extinction — and that he had to preserve a record while it was still possible. The project would become the 20-volume, 20-portfolio set of rare books, The North American Indian. But in 1900, he wasn’t sure what form it would take or how he would achieve it — he just knew it had to be done, and done soon. The project wasn’t finished until 1930, when the final volume and portfolio were completed. Today, it still stands as a landmark in North American publishing history and remains the most expensive and ambitious set of rare books in North American publishing history.

C&I: It was underpinned by a sense of urgency. Why was Curtis so concerned that American Indians were disappearing?

Cardozo: By the time Curtis began his life’s work in 1900, the Native American population on this continent had plummeted from an estimated 20 million to a mere 250,000. There were still individuals actively advocating for the extermination of all Native people in North America. Most had been forced onto reservations and the U.S. government had adopted strict policies to strip Native people of almost every vestige of their culture, their land, and their identities. They were essentially refugees in their own lands, subjected to extreme cultural genocide. It was within this context that Curtis discovered his life’s purpose and single-mindedly pursued it for decades.

C&I: You often cite a particular Curtis quote: “It’s such a big dream, I can’t see it all.” Why?

Cardozo: Because it says so much. Curtis was an extraordinary visionary. When he wrote the quote in 1900, he had just begun an unprecedented multi-decade project that was so big it was impossible to grasp or understand. Yet, he knew in his heart that this was it: This was going to be his life’s purpose. That quote encapsulates and anticipates all the sacrifices and triumphs that would occur over the ensuing three decades. The enormity of what he would accomplish, what he would have to sacrifice, the lives he would touch, the people he would meet, the legacy he would create — these could never have been foreseen in 1900.

C&I: What kinds of sacrifices?

Cardozo: They are really too numerous and profound to enumerate fully, but in some ways to me the biggest sacrifice he made was at the very outset, in 1900: He gave up his lucrative career to focus on doing something for mankind. He had grown up in abject poverty. When he was young, there’d be weeks when his family ate nothing but potatoes and muskrat. Suddenly, he has a lucrative business as a high-society photographer; he’s making lots of money and supporting an extended family and employees. He’s made it. He was the photographer in Seattle, with crème de la crème clients. He gave it all up to pursue his dream of documenting Native Americans. He couldn’t have realized what the immense eventual cost to himself — financial, physical, and emotional — would be, but he had to have known there was great risk involved.

C&I: Some at very great risk to his personal safety. ...

Cardozo: In the early days, he used to take his family with him on his expeditions. Once on Hopi or Navajo land near Canyon de Chelly, a local medicine man came to him in urgency in the middle of the night and instructed him to leave immediately because a Native woman was in labor. Curtis was told that if she died, he’d be blamed. After that, he decided that as hard as it would be, he’d never take his family with him again — and he didn’t till his kids were grown. There was also a time when a packhorse slipped over the side of a canyon, and he lost not only the horse but weeks of glass-plate negatives. He endured almost every physical hardship imaginable while in the field.

In 1914, when World War I began, he and his company were insolvent and he had to suspend work for seven years. When he resumed in 1921, he was in his early 50s and had had two breakdowns already, on top of lots of physical injuries. By 1926, the last thing he had of any value were his copyrights; he used those to collateralize a loan and went back to Alaska to photograph with his daughter, Beth, and an assistant. He was never able to repay the loan.

C&I: Before it got desperate financially, how did he travel with all that gear?

Cardozo: He traveled by every way imaginable — other than comfortably. Horseback, wagon train, canoe, kayak, sailboat. In the early days when J.P. Morgan was financing the project, he had camp cooks, photo assistants, and camp hands. I’ve read he had as many as 50 to 60 people, including translators and film and sound assistants. By the end, he was down to just his daughter and one assistant who was a translator.

When in the field, he typically lived in tents. There’s a photo of a little pup tent covered with snow in the mountains of Arizona, which was his author’s tent. He lived modestly in the little tent — out in the rain and snow, on the cold ground. His studio tent would have been five times as big as the tent he lived in. It had louvers on two sides to let light in, so he could get studio-type lighting. He would make prints in the field, called cyanotypes, using chemistry similar to an architect’s blueprint. Unfortunately, very few of those have survived. From what I can tell, he would have made at least one cyanotype for each negative — like test Polaroids. Almost all have been thrown away or lost. I have a small collection of some cyanotypes. They have a special magic, rawness, and immediacy. For me they are profound because I know Curtis literally held them in his hand and the Native people saw them. It is like being transported back to the moment of their creation.

C&I: Not everyone he photographed was an unknown. Who are some of the more well-known people who participated?

Cardozo: He photographed Geronimo, Red Cloud, and Chief Joseph, three of the most noble and important leaders of the 19th century. He and Chief Joseph were great friends, and Curtis was asked to participate in Joseph’s reburial ceremony. A reburial is a very sacred ceremony; to be among the few individuals invited to participate was a great honor.

C&I: Do you have a favorite image?

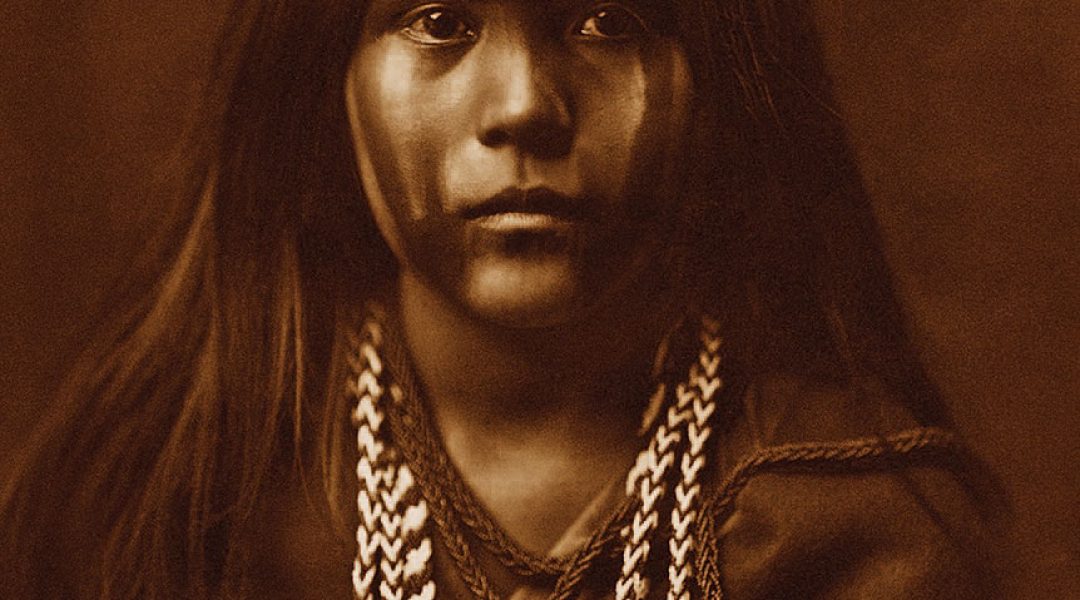

Cardozo: I have too many to count, but a few particularly stand out. The first Curtis image I saw in 1973 remains one of my favorites. It is titled Lummi Type. It is a very early Curtis photograph (1899). It has classic Curtis lighting and composition, hallmarks of his greatest portraits. The woman appears to be giving us access to the deepest parts of her being; there is an extraordinary sense of intimacy and presence. Finally, after waiting 44 years, I acquired a gorgeous platinum print of it in 2017.

I have another platinum print, A Walpi Man, that has also been one of my favorites for decades. First, it is a gorgeous photograph and has great “object presence.” Curtis’ platinum prints comprise only one-half of 1 percent of his work, so the rarity factor is also important. The image moves me because it’s beautifully made but more importantly because there is such intimacy, authenticity, power, and presence. You feel like you can connect with the sitter on a soul-to-soul level. He has consciously made himself available on a very deep, authentic level.

C&I: Did Curtis pay his subjects?

Cardozo: Only in unusual circumstances and primarily very early in the project. However, he often brought them gifts, tobacco, much-needed clothing, etc. These were not intended as payments, but rather as true gifts to show his respect and to follow Native etiquette, even though he was impoverished and the payments for these gifts came out of his own pocket. It was also a heartfelt acknowledgment of his great appreciation for their active and indispensable contributions as co-creators of the project.

C&I: Does it bother you that Curtis occasionally had people wear clothing that was not theirs?

Cardozo: No. Only the fact that people continue to bring it up and thereby distract us from the real value and meaning of the work. Critical analysis of over 2,000 Curtis images has shown that this rarely happened. Anthropology was a nascent discipline and this was a commonly accepted practice. The father of modern anthropology, Franz Boas, did it perhaps 10 times more often than Curtis.

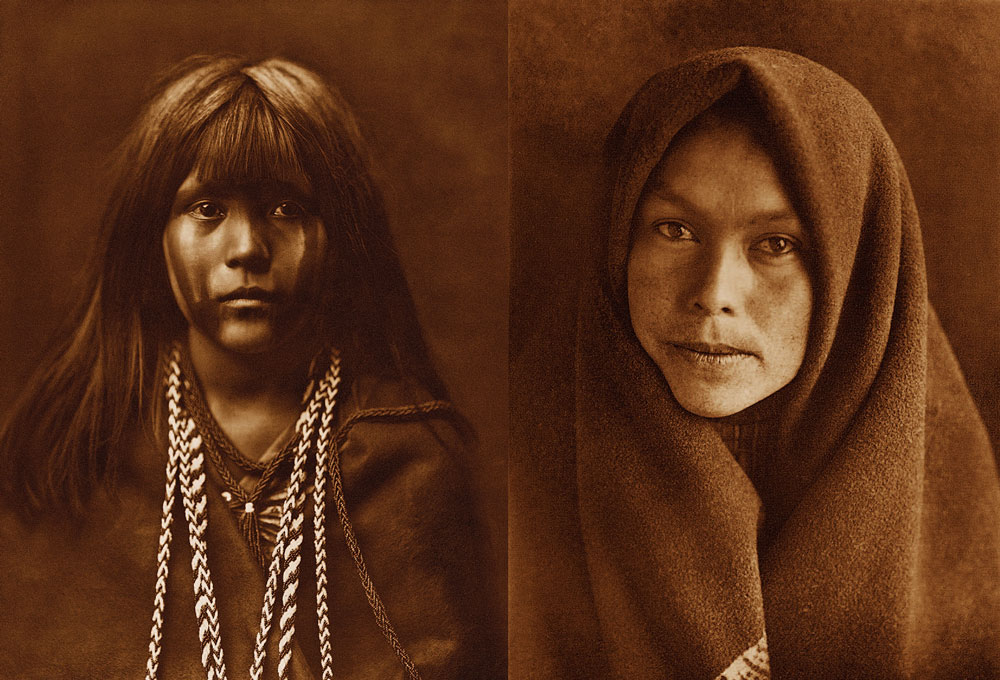

But more importantly, this concern misses the central value and intent: Curtis wanted us to see who Native people really were, in their essence. With his photographs, Curtis was not trying to create a document of how Native people existed as refugees, largely shorn of their culture and identity, but rather to create an artist’s impression of who they really were in their heart and soul. He wanted to show us a deeper truth.

I try to get people to see that this was a co-creative, participatory project. Look at the imagery and look at how present these people are. Curtis was engaging Native people in ways that were unprecedented for a photographer. He engaged them as equals and as co-creators. He engaged people who previously avoided any intimate connection with Caucasians. He was given personal and spiritual information that was shared with few, if any, other white men. In the end, he gave up everything to raise the money to finish the project. Imagine the aesthetic and historical void had he not stayed the course and sacrificed all to complete it.

C&I: How were Curtis and his project received?

Cardozo: He was front-page news from coast to coast for nearly a decade. He sold out Carnegie Hall. He crisscrossed the continent by train 125 times, giving lectures and presenting exhibitions. He created the first feature-length film on Native people. He was a Renaissance man — an award-winning photographer, a noted author, an artist, an ethnographer, a multimedia artist, and a pioneering environmentalist. All this with only a sixth-grade education.

C&I: Those rare books today can bring upward of $3 million for a complete set. What are they like?

Cardozo: Each of the 20-volume and 20-portfolio sets comprises 2,234 original photographs, 2.5 million words of illuminating and detailed anthropological text, plus extensive transcriptions of language and music. They are magnificent. They also essentially bankrupted Curtis and his company, even with J.P. Morgan as his lead patron. In today’s dollars, Morgan and his family contributed $10 million to the project.

Unfortunately, that only covered one-third of the total cost and Curtis was left to raise all of the additional money, as no publisher would touch such an expensive and complex project. The enormous expense of the fieldwork and the largely handmade publication kept the project in a a continual state of insolvency and prevented Curtis from drawing a salary throughout the project. Curtis managed to complete 214 sets (of a projected 500); others were completed after his involvement ended. Today, an estimated 225 survive, with only 20 to 25 in private hands.

The constant struggle and stress of being the photographer, author, researcher, lecturer, exhibiting artist, CEO, occasional camp cook, etc., left him so depleted he had two breakdowns during the 30-year project. Once it was completed in 1930, he was hospitalized for two years. He was penniless and utterly drained. The world had long since forgotten about him and his magnificent accomplishments. Happily, his daughter, Beth, with whom he had always been close, took him in and helped him get settled in Pasadena [California]. He lived there until his passing in 1952, at age 84.

C&I: When did people get interested again in his work?

Cardozo: Actually, after intense fame for nearly a decade, the advent of World War I in 1914 was the death knell of interest in his work; completing the project still took another 16 years. To survive, Curtis worked as a still photographer and cameraman on movies (including Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments). He also frequently took on mundane commercial assignments. The thought of Curtis being reduced to photographing weddings and such after years in the field with Geronimo, Chief Joseph, Red Cloud, etc., is particularly poignant. The early ’70s was the beginning of the “Curtis Renaissance.” I believe it was a confluence of a variety of factors: rapidly growing interest in fine art photography, the environment, and Native American lifeways, the American West, and spirituality. As popular culture reflected this more and more — Dances With Wolves, for instance — it also reverberated deeper and deeper within the Curtis world.

C&I: This year marks the 150th anniversary of Curtis’ birth. Why is his work still compelling and relevant in 2018?

Cardozo: It remains both relevant and compelling in an extraordinarily wide variety of ways. The power of the work, in part, lies in the fact that it’s so visceral — and important. It is compelling because, among other things, his work is exceptionally beautiful, intimate, and authentic. These are all healing traits and our modern world hungers for them. In this time of fake news and extreme divisiveness, many of us yearn for beauty, meaning, and authenticity. I have created exhibitions that have gone to more than 40 countries. And I have never gone to an opening or given a lecture on Edward Curtis where at least one person — irrespective of age, gender, language, socio-economic status, etc. — was not moved to tears.

Celebrating Edward S. Curtis in 2018

For more information about the republication of The North American Indian and 150th anniversary events, visit cardozofineart.com.

From the February/March 2018 issue.