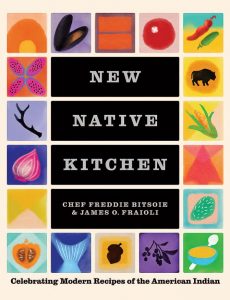

Freddie Bitsoie’s brand-new cookbook, New Native Kitchen: Celebrating Modern Recipes of the American Indian, brings the joy of Indigenous cooking to kitchens everywhere.

Freddie Bitsoie, one of the leading chefs specializing in Native American cuisine and a member of the Navajo Nation, wants us all to become more familiar with the foods of his ancestors.

Formerly the executive chef at Mitsitam Native Foods Café, located inside Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., he spent the last year testing and tweaking recipes for his first cookbook, New Native Kitchen: Celebrating Modern Recipes of the American Indian. Cowritten with James O. Fraioli, the book, which Bitsoie describes as a primer of sorts for Native American cookery, covers everything from how to stock a Native pantry to how to make a traditional Navajo soup with supermarket staples. Filled with stories behind the ingredients and recipes that are traditional for different tribes across the U.S., the cookbook is as much armchair entertainment as it is an actual recipe guide. The result: an easy and fascinating read from each headnote to finished dish.

Judging by the celebrity endorsements, we’re not the only ones who’ve been enjoying it. Robert Redford: “Thanks to Chef Freddie Bitsoie and this artful, inspiring book, it is easy to see how we can incorporate Indigenous foods into our kitchens and how the simple act of cooking can also be a celebration of Indigenous people, their rich cultural traditions, and connection to the land that has inspired so many delicious recipes.” Hopi-Tewa artist Dan Namingha: “Freddie Bitsoie has taken Native American cuisine to a new level.” Anishinaabe actor Adam Beach: “I am fascinated with Freddie’s knowledge of Indigenous foods. He always brings love and understanding to the experience of ancestral food culture. Meegwetch (thank you).”

We caught up with Bitsoie in Gallup, New Mexico, at his parents’ house, where he’s been staying since the pandemic began, with the idea of asking him for recipes for the holidays. “It hadn’t occurred to me to make some of these dishes for the holidays until I started working at Mitsitam,” he says. “One year around Thanksgiving, a guest ordered the bison tenderloin as a main dish instead of turkey — which is what my family always ate growing up — and it broadened my idea of what could be eaten and served for a festive dinner.”

We came away with recipes from New Native Kitchen fit for the holiday table (find recipes for Braised Bison Short Ribs, Glazed Root Vegetables, and Chocolate and Piñon Nutcake on Page 106) and an enlightening conversation with Bitsoie besides. As he says in his new book: “Like the French, who enthusiastically say Bon appétit! when sharing a meal, we celebrate in the Native language of the local Nanticoke-Lenape and Piscataway peoples: Mitsitam! Let’s eat.”

Cowboys & Indians: As a kid, you lived on various Navajo reservations across the Southwest, but you often visited your grandmother in Utah, where she lived on the reservation. You’ve often said that she was one of your biggest culinary influences.

Freddie Bitsoie: She would create these fascinating things like a stir-fry with sheep offal — chopped intestines, liver, and diced kidney — and it would be sautéed, and we’d eat it with a flour tortilla. She’d make a pot of beans and strain them and mash them and put butter on them and we’d eat them with a tortilla. Or she would make mashed squash. She’d boil it and then mash it up like a potato. This influenced me, and it’s how I create dishes now.

C&I: How so?

Bitsoie: Her dishes had a bit more complexity, and she used dairy more than my father’s mother did. Her food was more experimental. Her favorite thing was to roast chicken in a woodburning oven. As much as I’ve roasted chicken in an oven, I don’t know if I could do it with a woodburning oven. She would season it with salt and pepper. She lived on a mesa, and Cortez was a half-hour drive on unpaved roads. The reservation was a food desert — and is to this day. The only day she had the luxury to roast a chicken was the day that she bought it. She had no electricity to refrigerate it. She had a pit in the ground where she would keep things like jarred peaches. I remember how she would wrap the chicken in foil and wrap it in a paper towel when we had to see a medicine man. We drove on a dirt road in a Datsun pickup, and we waited on the medicine man’s porch. We had those Morton saltshakers we used to travel with, and we ate the chicken over the aluminum foil while we sat on the porch. I could hear the salt granules on the foil. Sometimes when I miss home, I’ll pull out aluminum foil and let salt fall on it just to remember that memory.

With deep symbiotic roots, there’s an interconnected trust between natural resources and the Indigenous communities who have always cared for the land where they live. Consider the three sisters, for example: The North American Indigenous planting method of sustainably growing squash, corn, and beans. Since the 1970s, people have termed the technique “permaculture,” but to traditional Indigenous farming practices, it’s simply a way of respecting the delicate balance of plants and earth, air, water, and fire.

— From New Native Kitchen

C&I: I also read that you learned to cook by watching PBS as a kid. Why did this fascinate you?

Bitsoie: We only had four channels, and when I was in fifth or sixth grade, on Saturday afternoons, I’d watch Julia Child on Great Chefs of the World on PBS. The many steps to make certain things was what I was fascinated by. When you season meat, you sear it, and then you start making something else. My father was a simple beans and potatoes person. My mom was usually a one-pot cook.

C&I: What was one of the first things that you cooked as a kid?

Bitsoie: I roasted a chicken from what television told me I could do. It was frozen. No one told me to make sure the chicken was thawed.

C&I: You were a cultural anthropology and art history major at the University of New Mexico before you left to attend cooking school. Your cookbook seems to be a marriage of all of these concepts. It’s as much a teaching tool about the different tribes and their culinary cultures as the recipes themselves, and the techniques behind them. Each headnote is a deep dive into the history of a particular ingredient in the proceeding dish. Who do you think your cookbook will appeal to?

Bitsoie: It’s a stepping-stone for those who want to dive into Native cuisine. The book is an introduction to Native flavors, and how flavors can be illuminated. It’s how people cook today. There are French techniques to certain dishes and Native techniques to others. They’re modern recipes, family-friendly, and easy to source — ingredients can be found at the corner supermarket or online.

C&I: How do you try to bridge the gap between these ancient cuisines and recipes and modern tastes?

Bitsoie: Our flavor profiles and taste are so very different from the ancient days, it’s impossible to assume what flavors a much older culture enjoyed. We can only assume by the ingredients that are from here and that have always been here that the flavors would be similar, but even a stainless pan and a cast iron pan give off a different flavor. But it’s not that simple. Salt, for example, has been in abundance for tribes that lived close to salt deposits, as opposed to those that were not. Convenience has as much to do with how food tasted then and now.

As a Navajo, it is imperative that I respect the myriad ingredients cultivated by Indigenous stewards of the land, air, and water in what we now call the United States. And as the executive chef at Mitsitam Native Foods Café in Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, I use that awareness to build varied menus that incorporate sacred Indigenous foodways with reverence. America is not, and has never been, a monolith. Just like Europe, it’s an expansive continent that’s incredibly diverse in terms of language, geography, culture, and more. But European countries like France and Spain are praised for their food traditions, which are taught in elite culinary schools; Indigenous cuisines, with similarly sourced ingredients and finessed preparations, unfortunately don’t get the same attention. My aim is to change that.

— From New Native Kitchen

C&I: Familiar ingredients are used in surprising ways in some of your recipes. For example, vanilla extract in potato soup.

Bitsoie: Yes, I love it. I think it adds a complexity to potatoes. It does not give it a sweet flavor but enhances the potatoes’ savoriness. Potatoes absorb a lot of flavor, and they have to be seasoned very well; they are like a stone to seasoning. The vanilla helps with that. However, too much is too much; just a little will go a long way. When I use coconut milk and just a dash of vanilla, it makes it taste so much better. But there are things I won’t change. The mashed beans that my grandmother made, I won’t change.

C&I: Many of your dishes feel like they’ve been adapted and modernized. Is that diluting them?

Bitsoie: No, because the essence of the flavor is there. Many families, Native or non-Native, have different ways of preparing food, and yes, adaptation and modernization will occur; there’s no changing that. The stories of the food and ingredients are what will keep the essence alive.

C&I: What do most people think of as Native American cuisine? What do they get wrong about it?

Bitsoie: The general public views Native American cuisine as boring, bland, and grainy. This is the one thing that I always come across. ‘How come the food is grainy, and how come the colors look horrible?’ People think it’s meat on the grill and that’s it. Teachers at the cooking school would say that Navajo food is horrible. Except fry bread. Everyone loves that. There seems to be a lot of misunderstanding as to what the cuisine style is all about. Native American cuisine is about holding onto family ways of processing, sharing, and preparing foods. You say a little prayer before you butcher a sheep, and everyone is there sharing stories, and kids are learning to butcher sheep. That’s how food culture is developed and maintained.

C&I: Is all food about storytelling, or is just Native American food about storytelling?

Bitsoie: It’s a combination of both. There are foods that are made for the sake of being made; however most complex dishes have a story of how the dish developed.

C&I: You’ve spoken about food not having real borders but imaginary ones. What does this mean when it comes to Native American cuisine, and why is it important that we recognize it?

Bitsoie: Because borders do not exist to Native foods. The Mexico-U.S. border does not exist when it comes to Native cuisine. It’s all about region and Indigenous ingredients.

Native American cuisine is about holding onto family ways of processing, sharing, and preparing foods.

C&I: Is there an iconic Navajo dish that you go back to time and time again? A comfort food for you?

Bitsoie: Summer Squash with Corn. It’s in my book. During the late summer, my mother, grandmother, and I would visit the local farms and buy their squash and corn. It’s not only a Navajo dish; many tribes have different variations of these two staples.

C&I: Five things that are always in your pantry?

Bitsoie: Kosher salt, agave, tepary beans — a wild bean from the Sonoran Desert that the tribes in Southern Arizona forage (I just stew them or make hummus with them) — jarred pasta sauce, and real maple syrup.

C&I: What would we be surprised to see in your fridge?

Bitsoie: Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups.

All excerpts and recipes from New Native Kitchen: Celebrating Modern Recipes of the American Indian by Freddie Bitsoie and James O. Fraioli (October 2021, Abrams) used by permission.

From the November/December 2021 issue.

Photography: (Cover image) courtesy Thosh Collins; (All others) courtesy New Native Kitchen: Celebrating Modern Recipes of the American Indian by Freddie Bitsoie and James O. Fraioli