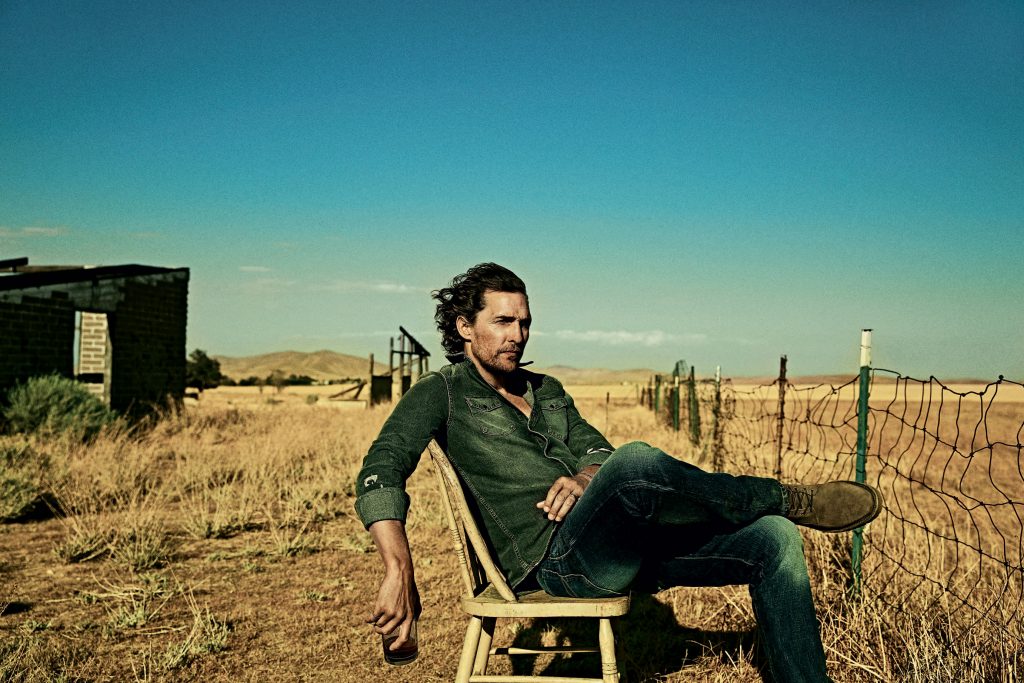

The Oscar-winning actor sits down with C&I to talk about his deeply personal memoir, Greenlights.

For Matthew McConaughey, Greenlights is more than just the title of his hugely entertaining and remarkably revealing memoir. It’s also a way of life for the Oscar-winning actor famed for his eagerness to just keep livin’.

Greenlights, he explains early in his book, are “affirmations of our way. They’re approvals, support, praise, gifts, gas on our fire, attaboys and appetites ... We love greenlights. They don’t interfere with our direction. They’re easy. They’re a shoeless summer. They say yes and give us what we want.”

On the other hand: “Greenlights can be disguised as yellow and red lights. A caution, a detour, a thoughtful pause, an interruption, a disagreement, indigestion, sickness and pain ... We don’t like yellow and red lights. They slow us down or stop our flow. They’re hard. They’re a shoeless winter. They say no, but sometimes give us what we need.”

Drawn heavily from journals and mementoes that McConaughey, now 51, has maintained for decades, Greenlights takes us down the long and winding road that started in his birthplace of Uvalde, Texas, reached a major turning point in Austin — where he made his big-screen breakthrough in Dazed and Confused (1993) as Wooderson, the role that enabled him to improvise his trademark “Aw right! Aw right! Aw right!” — and continues here and there to movie and television locations throughout the globe.

Photography: Courtesy Sunshine Sachs/via Wild Turkey

Just as important — indeed, arguably more important — Greenlights focuses on McConaughey’s defining relationships with his parents, James Donald McConaughey and Mary Kathleen McCabe, a couple given to raucous quarrels and passionate reconciliations. (As Wikipedia tactfully notes, they “married each other three times, having divorced each other twice.”) Later sections of the book are devoted to the actor’s current life in Austin with his wife, Camila Alves, and their three children, ranging in ages 8 to 12.

On a recent early spring afternoon, McConaughey agreed to Zoom in from the sunlit patio of his Austin home base to talk about his book, his career, and his roles as son and father. What follows are highlights from our conversation, edited for brevity and clarity.

Cowboys & Indians: Early in Greenlights, you remark: “I never wrote things down to remember; I wrote things down so I could forget.” When you were reviewing decades of notes and journals to write Greenlights, what did you come across that made you feel, yeah, I really wanted to forget that?

Matthew McConaughey: Well, going back and writing a book based on the last 50 years of my life — that was already an intimidating idea. I was like, “I’m going to go back, and I’m going to see things where I’m embarrassed, where I feel shame, where I feel guilt. I’m going to see things where I was an arrogant little know-it-all prick, and I’m not going to like it.” And I did see all those things.

But most of the things I was embarrassed about, I ended up laughing at. Most things I felt ashamed or guilty about, I’d either forgiven myself for, or forgave myself for. And then, whenever I saw myself as an arrogant little prick in my life at times, I noticed that, each time, soon after, I got humiliated and humbled, and I was all of a sudden like, “Well, if you wouldn’t have been the arrogant prick, you might not have had the confidence to put yourself in that position to get you humbled.”

I’ve actually got to say, I enjoyed going back through that year in Australia. While I was in it, I was like, “Whoa, when’s this going to be over?” But I’ve got enough room and distance in my life from then that I know if that wouldn’t have happened, if I wouldn’t have had that year, I don’t think I’d be sitting here talking to you about the life I’ve got so far.

But most of the things I was embarrassed about, I ended up laughing at. Most things I felt ashamed or guilty about, I’d either forgiven myself for, or forgave myself for.

C&I: No regrets?

McConaughey: Well, there were a lot of red lights that I looked at. Like lying to my dad. I still wish I wouldn’t have done that. And that pizza story. I felt ashamed about that for a long time, and wished I was man enough to just own up and tell him the truth, because the lesson on that one, kiddos, if you read the book, is: If you stole a pizza tonight for dinner, and you get home when your dad’s up, and he asks, “Did you pay for that pizza?” — it means he knows you didn’t. So, don’t lie about it. But I tried to weasel my way out of it.

So that’d probably be the one thing I still regret the most, because I remember seeing the pain and anguish on his face, of his feeling like he was failing as a father if he had a son who sat there and lied to him four times to his face.

C&I: In your book, you write that, years later, when you called your father to tell him you were switching your major from law to film at the University of Texas, you were surprised and relieved by his unconditional encouragement. Do you think you might have hesitated to make that fateful move had he disapproved?

McConaughey: That’s a great question, because one of the things that I’ve noticed while looking back was, let’s say that conversation took 15 seconds. I call. “Hey, Pop, what you doing, monkey man? I want to talk to you about something.” “Yeah, what’s that, buddy?” “I don’t want to go to law school anymore. I want to go to film school.” Pause. “Are you sure that’s what you want to do?” “Yes, sir,” I immediately come back and say. Pause. “Well, don’t half-ass it.”

Now, however long that just was, 15 or 20 seconds, part of the reason I believe he said, “Don’t half-ass it,” is, he heard in my voice that I really wasn’t asking his permission. He heard the conviction in my voice that I wouldn’t go on. I didn’t say, “Well, I think maybe it’d be cool if I went to film school, and I think that’s what I want to do.” I think if I would have stuttered, or if he’d been able to tell that I hadn’t given it my own thought, and hadn’t really put my time into it for myself to make that decision, I think he would have said, “Well, that sounds great, boy, but you can do that on Saturdays. You’re going to have to get a real job. You ain’t doing that. I ain’t paying for that.” But I think he heard in my voice that I really wasn’t asking him permission. And he heard in my voice that I wasn’t bluffing when I proposed it to him.

C&I: So that was a major turning point for both of you?

McConaughey: One of the things I think any parent wants is to raise their children to learn how to block and tackle, and stay in your lane. There are rules and regulations. But one of the proudest days is when your child decides they’re going out of the category you gave them and going their own way. And they come to you and say, “This is what I’m doing. I’m not asking permission.” I think in that moment on that phone call, my dad heard my voice and was inside going, “Yes. I have succeeded as a father because I helped raise a son that’s confident enough to come to me and go, ‘Dad, I know what I want to do, and I’m going to do it.’”

I can’t imagine him saying anything else now. Again, if I had stuttered and said, “I think, well, I mean, maybe it’s a good idea,” I don’t know what he would’ve said. He wouldn’t have said don’t half-ass it. He’d probably at least said, “I want you to think on it some more, son, because I’m not quite hearing you. I’m not hearing a son that’s convinced himself yet.” But he heard in my voice that he had a son that had convinced himself.

Photography: Miller Mobley

C&I: Decades ago, I interviewed Michael Caine, who told me that at the time his father was dying, the old guy really thought of his son as a failure, a struggling actor who couldn’t find work and wouldn’t be able to take care of his widowed mom. And Caine practically had tears in his eyes when he said, “You never get over that.” You were blessed to not have that problem — you were already days into filming Dazed and Confused, which would be your breakthrough film, when he passed away. He not only was not ashamed of you, or think you were a failure, he was expecting big things from you in your field. Right?

McConaughey: I think so. Look, I’ve always seen that as a great state of grace, the fact that my father was alive, that his life here and my life [as an actor] overlapped. He lived five days into me starting what would be more than a fad, what became a career. And that’s the first thing in my life that I got to start that wasn’t a fad.

I remember one summer when I was younger asking him: “I want a skateboard. Can I get the elbow pads and the knee pads?” “Well, I don’t know, son. Money’s tight. Are you sure you want to ... ?” “Dad, I promise you, I really want to do this. I’m going to practice and everything.” Shit, I practiced for about two months and quit. It was a fad. I always felt like, “Damn it. You really talked Dad into buying you those elbow pads and knee pads, but you didn’t really commit to that.”

So for him to be alive for the first time that his son started something that would not turn out to be a fad — to me, there’s grace and serendipity in that. I don’t mean he thought anything like, “Aw, now I’ve got my final son off doing what he’s doing. Now I can pass away.” I don’t think those two things were related. But I do go, in hindsight: “Oh, that’s really graceful that that happened, that his life overlapped with me starting what would become a career.”

C&I: In Greenlights, you mention your immediate reaction after your father passed away: “It was time to trade in any red sports car I still had. It was time to stop dreaming and start dealing. It was time for me to take care of mom. It was time for me to take care of myself. It was time to sober up from boyhood whimsy. It was time for me to get real courage. It was time for me to become a man.” What did being a man mean for you then, and what do you think it means for you now?

McConaughey: Well, then it meant maybe I was only giving 80 percent, because I had a safety net, my dad. I had a crutch if I really needed it, my dad.

Well, he moved on, and that wonderful, abominable snowman of a man who I didn’t think could die was physically no longer here anymore. And I was like, “You ain’t got nobody to catch your back when you fall now. You don’t have that crutch anymore. You don’t have that man to rely on, so you better take ownership of what you’ve been kind of half-assing, Matthew, and have courage to become that man, because you can’t be relying on your old man having your back anymore. Because he ain’t here.”

C&I: And now?

McConaughey: I know more of what I’m about now, and who I am and where I want to go than I did then. Back then, I was still in the middle of early years of defining what I was not, who I did not want to be. A process of elimination leading me towards where I am now. I have a vision of where I want to go, and why. I’m still working on the how, but I’m much more affirmative now. I’m not just getting rid of things I don’t want. I’ve built a life and customized a life, and built a vision and a lane in front of me with things that are non-negotiable in my life. With my family, my mom, my wife, my kids, myself, I’m going, “These are non-negotiable. I’m taking care of these, and wherever I go they’re going with me.” I know where I want to go. As I said, not always sure exactly how to get there. But I know why and where I want to go.

Photography: Courtesy Sunshine Sachs/via Getty Images

C&I: How often do you find yourself talking to your three children, and suddenly realize you hear your father’s voice in yours?

McConaughey: Often. Quite often. I engage with my children. And I know I explain a lot more than my dad explained to me. My dad was more like, “This is what you do. I’ll give you some reasons why, but after that, if you don’t understand it, it’s because I said so.” That’s it. And there’s great value in that. But I’ll go past that. I’ve chosen to engage with them when they ask, “Why?” I’ll be like, “Well, let me help you understand it more.” I probably over-explain some, and probably could have used that “because I said so” a few times, but I’m trying to give my kids the chance to understand. And me the chance to contextualize it, and then challenging myself as a communicator and storyteller to go, “Wait, how can I give this lesson where an 8-year-old understands it?”

C&I: Do they ask many questions about what their father does for a living?

McConaughey: The two oldest, I think, get it pretty completely now. The youngest, maybe not so much. And mind you, they haven’t been able to see 90 percent of my movies. They are not appropriate for them yet. When they see those, that’s going to open up a whole ’nother bunch of sit-downs. That’s the reason I started doing voiceovers in some animated movies and TV shows. Because I got tired of hearing the question of “What’s your kids’ favorites of all the stuff you’ve done?” You know what I mean?

C&I: So you think it will be awhile before you show them, say, Dallas Buyers Club? Or Magic Mike? Or Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation?

McConaughey: [Laughs.] We might want to give those a few more months, don’t you think?

Greenlights (Crown Publishing Group) is available wherever books are sold. For an added treat, check out the McConaughey-narrated audiobook version. A podcast version of the Hank the Cowdog series is also available on all podcast platforms, featuring the actor voicing Hank.

Photography: (Cover image) Courtesy Sunshine Sachs/via Getty Images

From our May/June 2021 issue