To celebrate the iconic actor’s life, take a look at his work in westerns.

Kirk Douglas played everything from a rebellious Roman gladiator (Spartacus) to a fearless Greek adventurer (Ulysses), from a morally outraged army officer (Paths of Glory) to a morally challenged Hollywood producer (The Bad and the Beautiful), from Vincent van Gogh (Lust for Life) to Gen. George Patton (Is Paris Burning?) to, in a 1973 made-for-TV musical, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

But on the occasion of his passing — the award-winning actor, producer, director, and author died Wednesday at age 103 — we at C&I wanted to pay our respects by paying special attention to the westerns on Douglas’ resume. Here is a list of 10 films we originally compiled on the actor's 100th birthday, a roundup demonstrate the remarkable range and diversity of his work in our favorite movie genre. And keep in mind: These are just some of the credits that earned for Douglas his 1984 induction into the Western Performers Hall of Fame at the National Cowboys & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Man Without a Star (1955)

Dempsey Rae (Douglas) is the title character, a straight-shooting drifter who lacks both a lawman’s badge and a clear sense of direction as he wanders into a range war between an unscrupulous lady rancher (Jeanne Crain) bent on taking over all the open range in Wyoming, and owners of smaller spreads who must use barbed wire to protect grazing land for their own herds. Rae hates barbed wire, lusts for the lady rancher — and serves as mentor for a novice cowpuncher (William Campbell) who proves to be an all-too-apt pupil when Rae teaches him how to handle a gun. Douglas smoothly runs the gamut from smug stud (the movie indicates he’s getting more than cash as compensation from Crain’s amoral rancher) to psychologically (and physically) scarred misanthropist to, inevitably, reluctant defender of underdogs in director King Vidor’s formulaic but entertaining drama, which was indifferently remade in 1968 as A Man Called Gannon with Anthony Franciosa in the lead role.

Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957)

Easily the very best of the many movies that paired Douglas with close friend and frequent collaborator Burt Lancaster, director John Sturges’ well-crafted account of the legendary showdown between the Clanton gang and Team Wyatt Earp (scripted by novelist Leon Uris) is neither as sentimentally mythic as My Darling Clementine (1946) or as guns-a’blazin’ exciting as Tombstone (1993). Rather, it’s a dramatically tense and psychologically intense western, very typical of ’50s cinema, with a surprising amount of screen time devoted to the sadomasochistic relationship between a brazenly suicidal Doc Holliday (Douglas) and Kate Fisher (Jo Van Fleet), his slatternly sometime lover. There are Howard Hawks-style gestures of male bonding on display as Sturges charts the relationship between Lancaster’s stern but fair Wyatt Earp and Douglas’ cynical yet loyal anti-hero. (Note how, at one point, Doc pours himself a drink, but Wyatt claims it; a few scenes later, Doc gulps down the whiskey Earp poured for himself.) And there’s something ineffably moving about Douglas’ fatalistic tone as Holliday explains why he’s placing his bet on Earp: “If I’m gonna die, at least let me die with the only friend I’ve ever had.”

Last Train from Gun Hill (1959)

Douglas re-teamed with director John Sturges for this lean and mean western about a gunfighter-turned-marshal who’s determined to follow the letter of the law even as he tracks down the men who raped and killed his Indian wife. Matt Morgan (Douglas at his most righteously badass) follows a trail that leads to Gun Hill, where he discovers one of the culprits (Earl Holliman) is the son of an old friend, Craig Belden (Anthony Quinn), a powerful rancher who controls everything (including the local sheriff) in town. There are sly echoes of High Noon and 3:10 to Yuma in the screenplay credited to James Poe — and some juicy additional dialogue from uncredited, then-blacklisted scriptwriter Dalton Trumbo, who would later help break the blacklist by getting screen credit for Spartacus. (As Glenn Lovell notes in his biography Escape Artist: The Life and Films of John Sturges, Douglas secretly hired Trumbo to write, among other things, a knockout-powerful scene in which Morgan tells his wife’s killer just what happens to a man when he’s hanged.) Quinn is terrific as the town boss torn between his love for his son and his friendship for Morgan, but Carolyn Jones is even better as Belden’s mistreated mistress, who returns to Gun Hill after being hospitalized for injuries she sustained during a beating from Belden, and winds up being Morgan’s sole ally as the lawman seeks rough justice.

Lonely Are the Brave (1962)

On several occasions, Douglas has claimed this contemporary western — adapted by Dalton Trumbo from Edward Abbey’s 1956 novel The Brave Cowboy — is his favorite among all his films, and it’s easy to see why. Jack Burns, the free-spirited cowboy who gets himself arrested to help his best friend break out of jail, only to find his buddy has no desire to join him on a fugitive flight from the law, may be the best role Douglas ever has had the good fortune to play, and certainly ranks among his greatest achievements as a film actor. When Burns realizes his pal, who was arrested for helping undocumented workers cross over from Mexico, isn’t willing to spend the rest of his life on the run, he sets out alone on his faithful horse to take a hard ride toward the border, all the while dodging a manhunt led by a sheriff (Walter Matthau) who comes to grudgingly admire the man he is chasing. Very much a movie ahead of its time — just a few years later, moviegoers of all ages, but especially younger ticketbuyers, were much more accepting of an anti-establishment individualist like Burns — Lonely Are the Brave has proven to be timeless in its enduring appeal. It should be noted, by the way, that David Miller, the director of Lonely Are the Brave, went on to direct Michael Douglas, Kirk’s son, in his first feature film, a 1969 drama about a morally conflicted Vietnam War enlistee titled Hail, Hero!

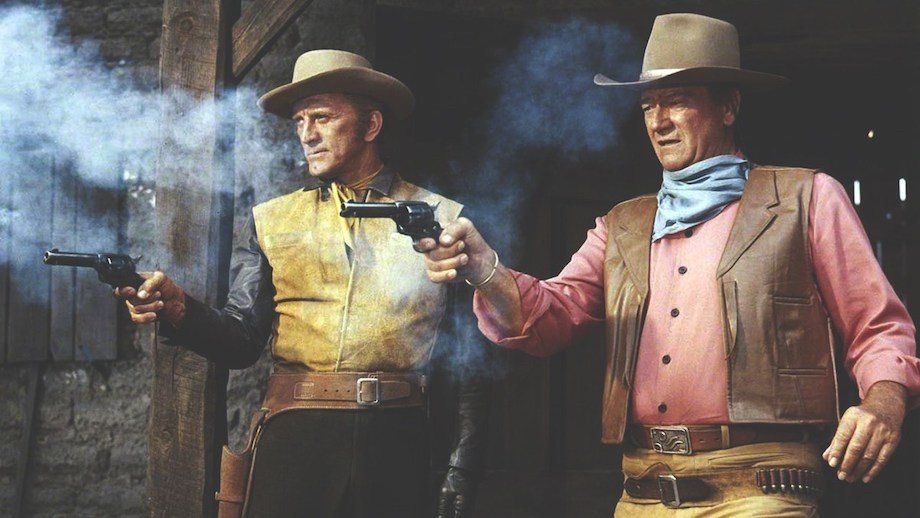

The War Wagon (1967)

Call it a Wild West heist movie, and you won’t be far off the mark. When cowboy Taw Jackson (John Wayne) is paroled from prison three years after being framed by greedy mining-company boss Frank Pierce (Bruce Cabot), he seeks revenge against the bad guy — and the return of his gold-rich land — with an audacious assault on the steel-plated, heavily guarded “war wagon” Pierce uses for cross-country gold dust shipments. Chief among Jackson’s co-conspirators: Lomax (Douglas), a flamboyant gunfighter who’s introduced in a saloon/brothel where he sports a dragon-bedecked silk robe while enjoying the company of two Chinese prostitutes. (When Jackson complains about the presence of the latter during a confab, Lomax grins and explains: “Can’t get more private. Neither one of them speaks a word of English.”) Slow-burning Wayne and live-wire Douglas develop a richly amusing give-and-take under the efficient direction of genre specialist Burt Kennedy, and are at their best when trading quips before, during and after gunplay. “Mine hit the ground first,” Douglas brags after they dispose of two would-be assassins. Wayne dryly responds: “Mine was taller.” Take note of Douglas’ casually dazzling physicality: You could organize a drinking game in which players take a shot each time he gracefully leaps onto a horse.

The Way West (1967)

Douglas often appears to be channeling John Wayne’s obsessive cattle-driver Thomas Dunson from Red River in director Andrew V. McLaglen’s leisurely paced epic, based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by A.B. Guthrie Jr. about an 1843 wagon train led by a former U.S. senator “to plant a New Jerusalem in the Oregon wilderness.” William J. Tadlock (Douglas) will stop at nothing and sacrifice anyone to fulfill his dreams of establishing a settlement in the Pacific Northwest. In pursuit of what he views as the greater good, he places onerous demands on the folks who signed up for the journey from Missouri — and goes so far as to execute a fellow pioneer for accidentally killing the son of a potentially troublesome Indian chief. There’s something slightly icky about the comic relief provided by an impossibly young Sally Field as sexually voracious teen. (“If we don’t get that girl hitched between now and Oregon,” her father frets, “she’s gonna run off and marry the nearest buffalo!”) And there are times when the melodrama is amped to a point perilously close to high camp, particularly when Tadlock, feeling guilty and grief-stricken after the death of his young son, demands to be punished with a bullwhipping. Still, Douglas brings undeniable authority to even the over-the-top episodes, and he gets invaluable support from Robert Mitchum as a trail scout who perseveres despite his failing eyesight, and Richard Widmark as a farmer and family man who’s compelled to satisfy his wanderlust.

There Was a Crooked Man… (1970)

Throughout his decades-long film career, Douglas has portrayed more than a fair share of scoundrels, varmints, and criminally inclined incorrigibles (including the title character in Scalawag, a rather unfortunate 1973 semi-western retooling of Treasure Island). But this darkly comical revisionist western, directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz (All About Eve) from a script by Robert Benton and David Newman (Bonnie and Clyde) arguably is the only movie that ever cast him as an out-and-out sociopath. And a pretty dang charming one at that. Backed by a dream-team supporting cast of Warren Oates, Burgess Meredith, Hume Cronyn, John Randolph, and Martin Gable, Douglas is at the top of his game as Paris Pitman, a purposefully charismatic outlaw who exploits everyone — including a reform-minded warden skillfully played by Henry Fonda — while plotting to escape from prison and regain his ill-gotten gains.

A Gunfight (1971)

When former gunslingers Will Tennary (Douglas) and Abe Cross (Johnny Cash) cross paths in a small Old West town, they surprise no one more than themselves by becoming fast friends. But they’ve come a long way from their heyday — Abe’s barely scraping by as a gold prospector, while Will is the celebrity bouncer in a saloon. And so, tempted by the promise of a hefty payoff, they participate in a deadly spectator sport. Specifically: They agree to sell tickets to their eagerly awaited shootout in the town’s bullring, where locals can place bets on the outcome — and a cash prize will go to one, but only one, of the main attractions. Douglas and Cash are perfectly matched in director Lamont Johnson’s arrestingly potent drama about two lethally talented men who take advantage of their own notoriety (at one point, they demand payment before posing for newspaper photos) while taking one last shot at, if not riches, then relevance. Footnote: A Gunfight was financed by the Jicarilla Apache Tribe, but there are no Native American characters on screen. Maybe the investors just wanted to see palefaces shooting at each other?

Posse (1975)

For his second effort as a feature film director, after the aforementioned, highly forgettable Scalawag, Douglas concocted with scriptwriters William Roberts and Christopher Knopf a scabrous Wild West morality play, at once deadly serious and savagely witty, about a celebrated Texas lawman who hopes to launch, with a little help from his all-star posse, his campaign for the U.S. Senate by capturing a notorious bandit. Douglas makes a memorable impression as Marshal Howard Nightingale, a preening hypocrite who travels with his very own publicity photographer. But as a filmmaker, he generously cedes most of the script’s best lines to Bruce Dern, who gives a career-highlight performance as Jack Strawhorn, a cagey outlaw skilled at bringing out the worst in everyone.

The Villain (1979)

Perhaps the most demanding test for a great actor is finding a way to make a bad movie at least tolerable for an audience. The Villain, a lame attempt at a satirical western in the style of a live-action Looney Tunes cartoon, is a very bad movie; indeed, the timing is so off during some scenes, you can’t help suspecting director Hal Needham (Smokey and the Bandit) fell asleep while the cameras were running, leaving the actors to desperately vamp until someone else yelled, “Cut!” But while costars Arnold Schwarzenegger and Ann-Margaret appear hopelessly adrift, Douglas gleefully serves up heaping helpings of spirited slapstick and inspired self-parody while playing what might best be described as the Wild West outlaw equivalent of Wile E. Coyote. That’s all, folks.