Still fantastic at 40, one of the best-loved horse movies of all time almost didn’t get made.

It was 3 a.m. when Carroll Ballard’s phone rang with a call from Francis Ford Coppola, who was then in Sicily filming The Godfather: Part II. The two had gone to film school together at UCLA and the middle-of-the-night call was Coppola telling him he thought they should do a film together. Months and ideas later, Coppola sent Ballard a copy of a novel that producer pal Fred Roos had heard about from his then girlfriend. It was her favorite childhood book: The Black Stallion.

“I didn’t like the book when it was first presented to me,” says Ballard, 83, in a rare interview at his hilltop home in St. Helena, California. “I thought, What is this? Leave It to Beaver? I wanted to make War and Peace!” But he finally “wised up” about the opportunity at hand, and in a truth-is-stranger-than-fiction convergence of events — including a typhoon in the Philippines that destroyed the set on Coppola’s Apocalypse Now — the modern classic, turning 40 this October, came to life.

Ballard munches on a quesadilla in a sunroom looking out on the pond flanked by his vineyard, as recollections of years spent on his visual masterpiece return. “I wondered for a long time, How is it that this book became such a big hit. Because I was dwelling on the old trainer and the kid talking,” he says. “Stuff I thought was totally predictable. But, there is this thing. I really didn’t see it for a long time. There is a mythic element in the book. It’s every child’s desire to have a powerful friend who can do things and who will make him powerful too. That’s what’s in this film. It’s mythic and in the form of a black horse.”

Based on Walter Farley’s 1941 children’s novel, The Black Stallion is the story of a young boy named Alec Ramsay who survives a fiery shipwreck off the coast of North Africa. The accident kills his father (played by Hoyt Axton) and the boy finds himself stranded alone on a deserted island with a wild Arabian stallion that he befriends and names The Black. Later, after Alec is rescued, he returns — with the horse — to his newly widowed mother in America. There, after meeting a once-successful retired racehorse trainer who helps him enter a match race between two champions of the track, he puts his bond with The Black to the test.

Turning Farley’s novel into a film proved daunting. “I could never figure out how we were going to put the two parts of the story together,” Ballard says. “I agreed to try and make a movie, but it was three years later that we finally got the go-ahead.”

Fate stepped in. “I don’t know that we would have, if it hadn’t been for this huge typhoon in the Philippines while Francis was shooting Apocalypse Now. It wiped out all their sets. It was a catastrophe. They had to cancel the whole production, and they all came back. He didn’t have any money to finish the movie. A way out for him was to sell the script of The Black Stallion to United Artists,” Ballard says.

The production was dead in the water, he says, when Coppola made the deal with United Artists to make the movie. “Nobody liked the script, but Francis had so much power in the business at that point that UA went for it — they green-lighted the movie. It would never have seen the light of day without him.”

But that was just the beginning of a whole new set of problems. “There we were with a script nobody was too interested in, and I did not know what this movie was going to be about,” Ballard says. “I had a few little ideas, and then we’re out there — 150 people and horses. What do we do now? Aggh! I think it was touch and go all the way through the movie whether we could pull the two halves of the story together.”

Ballard grew up on Lake Tahoe’s waterfront when the area was a wilderness. He originally intended to go into design, but an unplanned route to Hollywood started to take shape when he joined the Army and the sergeant in his unit had a film club. He faced immense logistical and creative problems in the making of The Black Stallion, and he’d never helmed a full-length feature film.

After film school, he’d made several documentaries for the U.S. Information Agency, Beyond This Winter’s Wheat and Harvest (the latter was nominated for an Academy Award), directed a short called The Perils of Priscilla, and made 1969’s Rodeo, which had Larry Mahan and Freckles Brown playing themselves in a look at the National Finals Rodeo back when it was in Oklahoma City. His first really big picture came in 1977, when he was the second unit director on Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope.

Eleven-year-old Kelly Reno had no acting experience. But the pairing of him with a black Arabian stallion named Cass-Olé proved a winning combination. Raised on a 10,000-acre Colorado ranch, Reno knew how to ride already and reportedly took the role because he wanted to learn how to swim. That was fulfilled by stunt coordinator Glenn “J.R.” Randall Jr., who booked Reno into a hotel with a pool near the Randall Ranch in Newhall, California, so he could teach him there. Reno spent half the day swimming and the rest of the day at the barn with horses. It wasn’t just a young lead and a horse that Ballard had to contend with. Besides another black Arabian named Fae-Jur, equine doubles ranged from sorrel Hollywood trick horses to gray “swimming horses” from the Camargue in France, dyed black for the role.

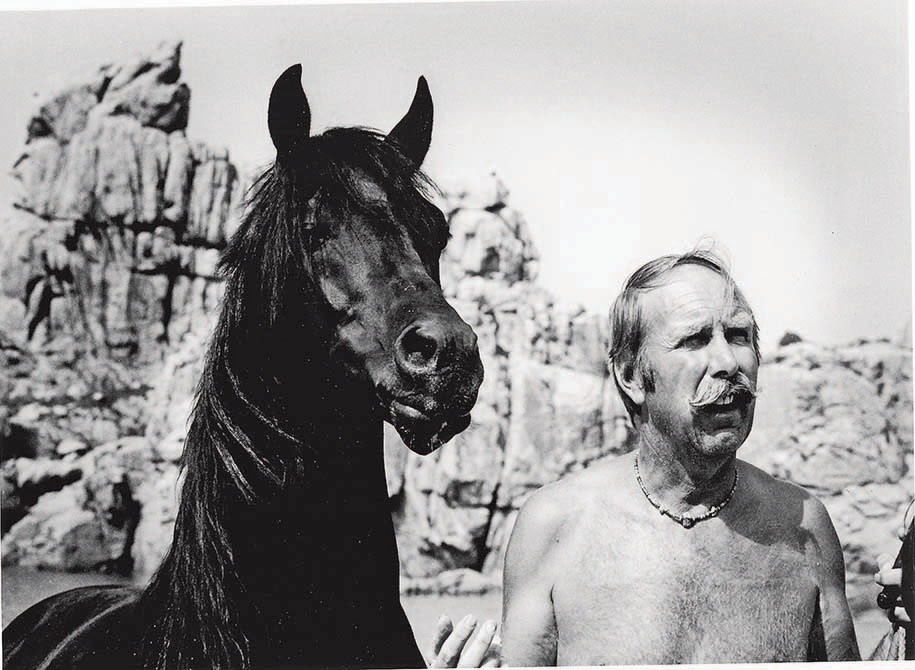

Though author Farley was a true horse lover, Ballard says they didn’t necessarily see eye to eye when it came to equine casting: “Fae-Jur was not his idea of what the Black Stallion should be. [The horse] was small and very feisty. I felt that was the magic horse. You could believe he was a spirit of some kind. Cass was a gorgeous horse — and big. He was magisterial.” Already a champion Arabian, Cass-Olé did the lion’s share of The Black’s performance on film and notched the starring horse credit.

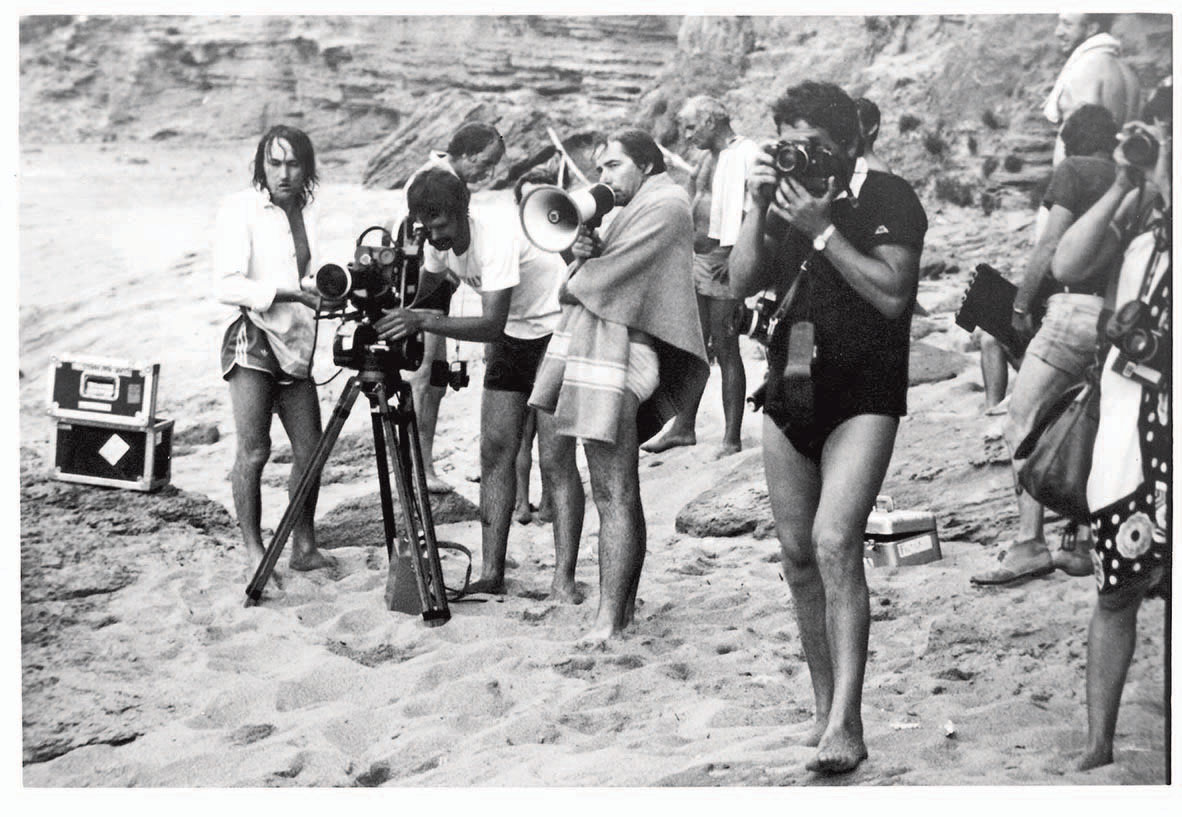

Featuring Mickey Rooney as ex-racehorse trainer Henry Dailey and Teri Garr as Alec’s mother, the last half of the story was shot first. “We filmed [the second half of the story] in about three months in Canada. Then we went to Italy to do the front part of the film,” Ballard says. The location in Italy was the island of Sardinia. “It was a very backward place at that time, and we were out in very isolated places,” Ballard says. “I told Francis we couldn’t shoot this according to a regular movie schedule. He said, ‘We’ll just take as long as it takes.’ We spent two months in some beautiful places with the horses. We did this and then we tried that.”

Horse trainer Corky Randall brought the talent and experience that allowed Ballard to capture some of the most challenging horse scenes ever filmed. The son of Glenn Randall Sr., who trained Roy Rogers’ Trigger, Randall was an established Hollywood ramrod (boss wrangler), when brother Glenn Jr. — the film’s stunt coordinator — convinced him to do the training. The Black Stallion would establish Randall’s legacy as a Hollywood horse trainer.

“Corky picked up that this wasn’t going to be the kind of movie where the horse is going to walk in here and do this and that. He could improvise,” says Ballard, crediting Randall for the signature beach scene where boy and horse become friends. “We were just shooting there on the beach and said, ‘Maybe we [can] do something here with Kelly and a little piece of seaweed and a close-up. Maybe we can get him going back and forth. Corky picked up on it and said, ‘OK, Carroll, where’s the frame line?’ Corky’s right out of frame when the horse is backing up and rearing and coming forward. The whole thing was done in one shot, and Corky did the whole thing. He just went in and did it.”

Not much of the filming happened that easily, especially the portion in Sardinia. “It was a tough shoot, the kind of shoot that Carroll Ballard loves, out there in the elements with a much smaller crew — everyone pitching in to carry gear — here, there, and over rocks,” says screenwriter Jeanne Rosenberg, who teamed with Melissa Mathison to create a whole new screenplay from scratch, sometimes literally writing scenes on the fly. “I didn’t go overseas, but Melissa was there. [Carroll] has an amazing eye and is quite a storyteller. ... There are so many angles — high angles and low angles and tracking shots — so many things that are so much easier now. Just send the drone out or put the camera on the cable. [But back then] it was so hard, and they did it so well.”

At a certain point, Ballard had to stop shooting in Sardinia and move the production to Cinecittà Studios in Rome to shoot the shipwreck sequence even though he still didn’t have all the shots he wanted from Sardinia. “There’s a tank — it was the same pond they used for Cleopatra,” Ballard says. (Tidbit: An old growling toilet at the editing location was recorded to create the sinking-ship sounds in the film.) “That was a month of nights — about five nights a week, every night all night. We finished the shooting in Rome, and I didn’t know how we were going to pull it all together. There were really important scenes I wanted to do on the island that I hadn’t gotten, things we couldn’t finish in time.”

One involved the snake scene, where The Black stomps a cobra about to strike the boy. “We’d made a deal with a movie snake guy. They promised the snakes had been defanged. They were real cobras. The day we were going to shoot, these two guys showed up in a little car and in the back seat they had two big baskets. They wanted to show me the snakes. I said OK, and out of this basket came this snake. It was the scariest thing you’ve ever seen. I said, ‘Gee, that’s really scary. I’m glad they’re defanged.’ The guy said, ‘They’re not defanged! We don’t do it that way. The way we do it is this,’ and he reached over [to] this little refrigerator. Inside was a hypodermic needle. He said, ‘If the boy gets bitten by the cobra, we just inject him with this.’ ”

Ballard details what followed as if it were yesterday. “A couple hours later, two grips come walking down the beach carrying this gigantic pane of glass. It was out of a store window from somewhere, and they put the glass on the sand and strapped it up. The cobra is on one side of the glass and the boy is on the other, and these cobras were scary. We filmed some, but we weren’t able to get enough angles on the snakes.”

Three months later, back in Sardinia, the weather had drastically changed. “We had two weeks to do pickups to fill in the holes. It’s so cold, the snakes can hardly move. So, how are we going to shoot this scene?” Ballard recounts the impromptu solution. “We’ve got to warm up the snakes. Let’s dig a hole in the sand and put some heaters down there so they heat up the sand. We’ll put boards on top and put sand on that. Meanwhile, the wind is blowing like crazy, the sheet of glass is moving around, and the sand keeps blowing against the glass and it’s sticking!” The exasperation he felt remains all these years later. “What we were trying to do was get a shot of the snake being scary, and we had this huge contraption and all the heaters going and the snake trying to warm up — this whole deal, trying to get one ridiculous shot of the snake.”

An entirely different scenario transpired at Cannon Beach, Oregon, late in the production. (Fortunately, Kelly Reno had not yet started growing facial hair or experienced a growth spurt.) “We just wanted a shot of Kelly riding Cass-Olé along the beach. It was long after we did most of the filming. We were just doing pickup shots. I was really worried about the hardness of the sand. I was worried Kelly might fall.” Ballard suddenly shifts into storyteller mode with a spot-on rendition of horse trainer Corky Randall’s voice. “ ‘Carroll, that little horse can’t outrun a flea.’ So we decided to do the run. We’re shooting along, it was going great, and all of a sudden Cass took off down the beach and disappeared into the sand dunes. It was terrifying. All Kelly had was that little wire bridle. It ended up being the footage we used.”

But for Ballard, that wasn’t the toughest scene to get right. “To me, the hardest, most crucial scene in the whole movie was the scene with his mom, where the boy tells her about the shipwreck,” Ballard recalls. “Kelly understood that was an important scene, and he had to express all the things to Teri [Garr]. He pulled it off. He made it believable.” This single scene linked the two parts of the film. “It pulled the whole thing together,” Ballard says. “It’s where the boy tells his mother about wanting to be in the match race with The Black. Of course she didn’t know he was secretly training for that and is furious and afraid. Then he pulls out the little Bucephalus horse figurine his father gave him on the ship before the wreck and tells his mother the story his father told him about Alexander the Great and his horse. By the end of the scene and what he shares, the mother agrees.”

When it was all put together, they had shot an eight-hour movie. “That’s why it took us a year-and-a-half to edit,” Ballard says. “There was so much, and we tried to somehow make sense of it. There is some beautiful footage, a lot of funny quirky scenes, but I [didn’t think there was] a way to string them all together. I think we extracted the story.”

Once completed, The Black Stallion got shelved by United Artists. “I thought the film was an utter failure,” Ballard confides. “The studio guys that came to see it thought it was unreleasable. They said, ‘What is this? Some kind of art movie for kids!’ ” Thanks to Coppola’s clout, The Black Stallion finally debuted at the New York Film Festival in October 1979 and quickly became a box office hit. Named the best film of the year by Roger Ebert, it earned two Oscar nominations, including one for Mickey Rooney. At the 1980 Academy Awards, The Black Stallion won the Special Achievement Award. At the Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards, the film won Best Cinematography for Caleb Deschanel, Best Music for Carmine Coppola (Frances Ford Coppola’s father), and the New Generation Award for Ballard. The timeless tribute to the horse-human bond was added to the National Film Registry in 2002.

Produced for under $4 million, The Black Stallion has grossed roughly $38 million.

“To me, it was always kind of a mystery how the film became successful,” Ballard says. “When I was making it, I felt it was completely out of control and I wasn’t going to be able to fix it. But there was enough continuum that kept everything in balance.”

As the sunroom grows chilly and Ballard prepares to head back to the main house, he shares a parting anecdote — and it’s a great one that reaches back to the days when he was making 1969’s Rodeo. “While we were filming, I heard this story about this bull called Tornado that nobody could ride,” he recalls. “It had been years, many rodeos, and nobody could ride Tornado. He was the most fearsome monster. At the [1967] National Finals Rodeo, Freckles Brown ... draws Tornado the bull and he rides him, and that night he could have become the governor of Oklahoma.”

Ballard later asked the Rodeo Hall of Fame cowboy what it took to ride a bull. “Freckles said, ‘Well, you’ve just got to feel it. You’ve got to feel where the center of gravity is and where it’s going next. And you get your head right there because that’s how you stay in balance on top of that uncontrollable movement that’s going on underneath you. You’ve just got to hear where it’s going and get your head right there.’ ”

For the director, it’s an apt analogy — for Rodeo, for The Black Stallion, for making movies in general: “To me it was always an interesting parallel,” Ballard says. “Making movies is sort of the same process. It’s kind of uncontrollable. It’s going all over the place. Every day it’s a whole other bunch of unpredictable events and you’ve got to get your head there to stay in balance.”

More about The Black Stallion

The Black Stallion’s Accidental Screenwriter

The Black Stallion at 40 With Stunt Coordinator Glenn Randall

The Black Stallion’s Secret Weapon

The Black Stallion at 40 With Production Assistant Tim Farley

Photography: (all images) Courtesy Tim Farley

From the November/December 2019 issue.