The Motion Picture Academy is honoring a longtime favorite of C&I readers.

Editor's Note: This story originally appeared in a slightly shorter form in the August/September 2019 issue of Cowboys & Indians.

Wes Studi had just finished a long of day of shooting on an upcoming film — Badland, the new western from writer-director Justin Lee (A Reckoning, Any Bullet Will Do) — when he picked up his phone and heard the good news: He would receive an honorary Oscar from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences during the Academy’s 11th annual Governors Awards on Oct. 27.

“I can’t tell you how honored and grateful this make me feel,” Studi told me when I called the next day to congratulate him. But then, with a touch of his characteristic dry humor, he added: “The only problem is — now I have to buy a new tuxedo. And a bow tie.”

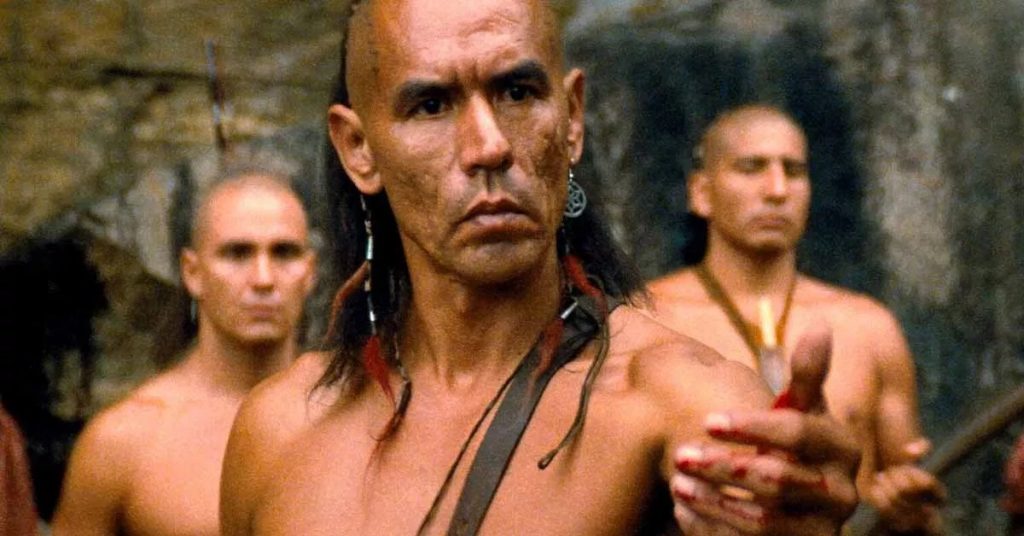

But seriously, folks: The prize is a richly deserved tribute to the Oklahoma-born, Cherokee-American actor, a widely respected artist and activist whose lengthy list of movie credits includes epic westerns (Dances with Wolves, Hostiles), period dramas (The Last of the Mohicans, Geronimo: An American Legend, The New World), contemporary crime stories (Heat, Undisputed), acclaimed indies (Powwow Highway, The Only Good Indian), comic-bookish adventures (Street Fighter, Mystery Men), and a record-breaking sci-fi box-office blockbuster (Avatar).

And mind you, that’s saying nothing of such equally impressive television credits as Crazy Horse, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Streets of Laredo, The Red Road, Hell on Wheels, and three TV-movies — A Thief of Time, Coyote Waits and Skinwalkers — based on novelist Tony Hillerman’s Joe Leaphorn mysteries.

By sheer coincidence, news of the Academy commendation came just a week after Studi and I had chatted about one of his many recent and ongoing projects, his stint as host of the Summer of Westerns series that continues through Aug. 11 on the HDNET Movies network. In the course of the interview, we also talked about many of the films in which he has appeared, including three — Jonathan Wacks’ Powwow Highway (1989), Michael Mann’s The Last of the Mohicans (1992) and Walter Hill’s Geronimo: An American Legend (1993) — that he views as turning points in his career. Here are some highlights from our conversation.

Cowboys & Indians: What do you remember most fondly about making Powwow Highway?

Wes Studi: Well, before that, I had done some television projects, but that was actually my first feature film. I think I had maybe three scenes in the whole thing. But one was a scene that’s stayed in many minds, as well as mine. It’s when I walk into a small café and talk with the two lead characters played by Gary Farmer and A. Martinez. I played it like the Indian cowboy that I am. [Laughs] Not that I had that much to do with cows. I kind of refer to myself sometimes as a horseman more than a cowboy.

C&I: Do you recall how you felt the first time you saw yourself on the big screen?

Studi: Yeah, I know my immediate reaction was, “Oh wow, I've got to find an acting coach.”

C&I: Well, you couldn’t have been that bad. Soon after that, you landed roles in Dances with Wolves and The Last of the Mohicans. Speaking of the latter film: You made quite an impact as Magua, the fierce Huron leader, warrior and industrial-grade badass. Did you ever find that people were scared of you in real life after seeing you play that character?

Studi: [Laughs] I noticed that people certainly did take notice when I was walking around afterwards. And I’ll tell you a funny story. After Last of the Mohicans, I was living in L.A., and I had a favorite newsstand that I went to, just right off Hollywood Boulevard. One day, I went there to look for a magazine that had pictures from Last of the Mohicans. I forget which one, but I think the movie might have been on the cover. So I’m standing there, gazing at the magazines on the stand there, and I notice off to my right in my peripheral vision two policemen just kind of eyeing me. And they’re probably thinking, “Are we looking for this guy? Do we recognize this guy? What is it about this guy?”

I just kept gazing at the magazines, though I’m sure I looked nervous by that point. Finally, they came walking over, and it was something like, “Say, you look kind of familiar to us.” I said, “Well, hopefully not.” The conversation went on, and then I showed them the pictures in the magazine that I had found by then, and said, “Yeah, well, I was part of this. Did you see this?” And they were like, “Oh, yeah, right, you’re that guy.” And so, ever since then, I've been kind of like, “Oh, yeah, you’re that guy” to many people. But I have to tell you: That incident gave me a bit of a scare there myself. [Laughs] Not that I had any warrants out on me or anything like that.

C&I: OK, I have to ask about Street Fighter, the 1994 movie based on the popular video game. I have to admit: It’s a guilty pleasure of mine, because my son was quite young at the time, and he was playing Street Fighter on his video game console all the time, and I think we saw that movie about three or four times in theaters. First off, did you play a lot of video games to get ready for playing the badass Victor Sagat?

Studi: I wish I had. Actually, I was unaware until I got on the set that the concept for the film came from a video game. We later on did some shots for an improved video game, wherein we did shots in a backward fashion, which is how you had to do things for that kind of filming at that point in time. It was fairly early on in that kind of technology. But, yeah, I was surprised that that was the case. That may have been one of the first few films that were done like that, taken from the video game.

C&I: Unfortunately it was the final film for Raul Julia.

Studi: Oh, I had some good times with him. Wonderful, wonderful actor, that guy. That’s how I saw him — an old-time Broadway actor, the real thing. He’d come to me and say, “Ah, yes, well, you and I, we must sit, we will drink tequila, yes, you and I.” He had that kind of grand gesturing — and yeah, he was quite the character. I’m honored to have worked with him, and I’m just sorry that that was his last real film.

C&I: You played Opechancanough opposite Colin Farrell and Christian Bale in The New World. What the first thing that pops into your mind when I mention the name of the director, Terrence Malick?

Studi: Waving grass and chickens.

C&I: [Laughs] Really?

Studi: Well, he’s a very interesting man, and has a great grasp of cinematography and storytelling. Everyone tells a story in a different method, and I love the fact that he has such a great eye and propensity for studying the human psyche. I think he’s a hell of a filmmaker.

C&I: The funny thing is, I vaguely recall reading an interview with Christopher Plummer a few years back — and your “waving grass and chickens” comment sounded an awful lot like something he said to the effect that he got the impression Mr. Malick was a lot more interested in the visuals of storytelling than dealing with the actors.

Studi: Well, that would be the first time I ever agreed with Christopher Plummer.

C&I: You had another opportunity to work with Christian Bale in Hostiles. And I must say: You were a dead-solid perfect match in that movie. Here you were playing a warrior at the end of his days, wanting only to return home, and he’s the cavalry officer who starts out so full of hate, but he has to escort you there. And then your characters somehow strike a reconciliation.

Studi: I think Christian is a consummate actor. And he’s in the moment. He’s not acting — he is being — and I think that’s one of the keys to his great performances. And his dedication to his character — oh my God! He puts so much effort into his character that I’m in awe of his dedication, his commitment to a character. He’s a great actor. And for a guy like me, he’s a great person that you can steal things from in terms of acting. So I’ve had I think two great opportunities to work with a magnificent actor, as far as I’m concerned.

C&I: What do you remember most vividly about — well, strike that. What are you proudest about playing novelist Tony Hillerman’s Joe Leaphorn character in three PBS movies?

Studi: Well, that’s contemporary, and that was one of the few films made, or television programs made, that looks at modern-day contemporary Native America. It certainly gained an audience beyond Indian country. In fact, that’s one of the things people ask me about most frequently: “When are you going to make more Tony Hillerman mysteries?” I think maybe the industry hasn’t clicked to the idea yet that audiences appreciate contemporary stories about Native America.

You know, it’s funny: It was back in the ‘80s when I first read one of Hillerman’s books. It was Skinwalker, and that’s one of them that we actually made into a [movie]. What I remember most vividly about the whole thing was when I began to read it, I asked myself, “I wonder when the white guy’s going to show up here and show Leaphorn and Chee how to solve this mystery that they’re working on?” And lo and behold, he never showed up. The Lone Ranger was absent from all of that. Nobody had to come and show Leaphorn and Chee how to solve the mystery. And I was amazed. That’s why I was so honored, much later on, to actually make as TV program for PBS that same story, Skinwalker.

C&I: Well, you got to play a Native American in another contemporary setting — a really nasty fellow, really — in the TV series The Red Road. Of course, you wound up getting killed by Jason Momoa, but…

Studi: That’s right — Aquaman killed me! How many people can say that?

C&I: Finally: Were you at all intimidated by the responsibility of playing the title character in director Walter Hill’s Geronimo: An American Legend?

Studi: I don't know that “intimidated” is strong enough a word. It was actually kind of overwhelming. Because in a situation like that, you begin to realize that this human being that you’re portraying is a man who had a huge effect on many people, and continues to do so to this day. And in this case, you’re also working with people who are actual relatives of his. Because there were descendants of Geronimo who worked with us on that film.

At the same time, there's a great expanse of opinions about what kind of man he was. Many opinions about him that have lasted from the time of his existence to this day, about whether he was good for the Indian people in terms of his stance, or was he not? How did he directly affect people in the past? Did his resistance cause more suffering for other Apache bands, as well as his own?

One of the things that I really enjoyed about the whole thing was, I learned a story about something that happened with him after the time we cover in the film. He was traveling from the Apache territory to Florida on the train. He had always been quite a trader. And he discovered while traveling on the train to Florida that he was a spectacle. So he took advantage of the fact that he was a spectacle.

C&I: How so?

Studi: At some point, he had gathered a lot of buttons from this cavalry jacket that he wore. And when he would make stops at different little towns during his travels throughout the Southeast, people would come to see him and marvel at Geronimo the warrior. What he began to do was sell the buttons off his coat to tourists and onlookers. He would just stand there and cut a button off his jacket and offer it to somebody, and they would pay him for it. And he did that until he got rid of all the buttons. Then he went back on the train, where he had a stash of buttons somewhere, and he would sew them back on before they got to the next town.

C&I: Sounds like he was a crafty guy.

Studi: Very crafty. Now, maybe that's a myth, I don't know. But on the other hand, I think it was a reflection of his humanity, actually.

C&I: Do you remember the day or the scene where you finally felt at ease playing Geronimo?

Studi: Yeah, actually, that question brings to mind a day where Gene Hackman [as Gen. George Crook] and I had a scene, a pretty extended dialogue. And there’s one point where Geronimo speaks to him, and he turns his back on Gen. Crook during their conversation. It’s convivial, but it’s a fairly aggressive kind of conversation they’re having as well. Well, after that, people who had been watching the scene came up to me and they said, “Oh my God, how did you do that?” I said, “What? What are you talking about?” “How could you turn your back on Gene Hackman?” I laughed, and I said, “Well, that wasn't me, that was Geronimo who turned his back on General Crook.”

C&I: Hey, that's why they call it acting.

Studi: [Laughs] That’s right. That’s why they call it acting.

What's New With Wes

What's New With Wes

Studi has been busy since we interviewed him for the cover story of our August/September issue.

First, the Oscar: On October 27, Studi made history as the first ever Native American Oscar recipient at the 11th annual Governors Awards, alongside fellow honorary Oscar honorees David Lynch and Lina Wertmüller.

His Hostiles co-star Christian Bale presented the award and noted that “Too few opportunities in film have gone to Native or indigenous artists,” a sentiment underscored by Studi.

“I’d simply like to say, it’s about time,” he declared in his acceptance speech. “It’s been a wild and wonderful ride, and I’m really proud to be here tonight as the first indigenous Native American to receive an Academy Award. It’s a humbling honor to receive an award for something I love to do.” Studi received a standing ovation.

And there’s more: On November 2, Studi co-hosts the 19th Annual Native American Music Awards at the Seneca Niagara Hotel & Casino in Niagara Falls, New York. (Music tracks from all the nominees are featured on the audio players on www.NAMALIVE.com. Anyone can vote by visiting the website VOTING page, or by clicking here.)

At the awards ceremony Studi will be inducted into the N.A.M.A. Hall of Fame. A musician as well as actor, he made his recording debut in 1995 with the group Firecat of Discord.

Meanwhile, Studi has collaborated with the national nonprofit Partnership With Native Americans (PWNA) for a new series of public service announcements highlighting realities on reservations and the need for giving.

The five-part Realities Video Series with Wes Studi addresses widely held misconceptions of Native American people, history, and funding. In it, Studi discusses history and treaties, realities on the reservations, education dreams and disparities, casino economics, and the lack of charitable giving for Native causes and communities, some of which mirror third-world conditions.

The partnership and PSA series were announced on October 4 at the third annual Native American Cultural Celebration hosted by the Museum of Native American History in Bentonville, Arkansas.

“As an American, and a Native American, it’s important to bring attention to the critical issues and disparities that Native people face every single day,” Studi said. “My hope is that together with PWNA we can increase awareness and show that supporting Native-led causes is the only way we can create change.”

Find out more at nativepartnership.org.