Wandering through Caprock Canyons State Park & Trailway, the little-known gem of the Texas Panhandle, offers peace of mind in a wild place.

I was bent beneath the weight of a full pack, trudging along a rocky trail that cuts across the north prong of the Little Red River, when my reptilian brain alerted me to the dark, humped form in my peripheral vision. I spun to see a solitary bison bull grazing no more than 15 feet away, half-hidden in the scrub oak and juniper. The buffalo eyed me impassively through dark, wide-set eyes. His heavy skull hung beneath a mound of muscle heaped atop shoulders at least six feet high. His thick horns hooked sharply, terminating at points fine enough to punch small holes through a leather belt. We regarded each other for a moment — the largest land mammal in North America and a writer from Dallas. Concluding, correctly, that I posed no threat, the buffalo returned to his grasses as I skulked away, slowly at first, then hurrying down the trail.

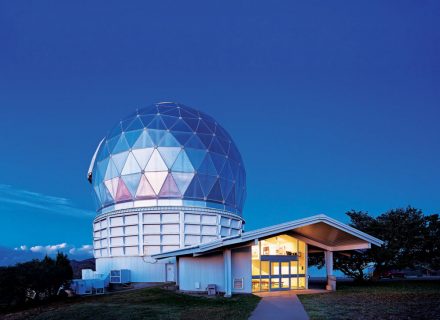

Though 15 feet was perhaps too close to a wild animal known for occasionally goring tourists, I had come to Caprock Canyons State Park in part because of the promise of such unmediated encounters with rare and free-roaming megafauna. The park is home to the last herd of Southern Plains bison on the planet, saved from extinction nearly 150 years ago by none other than legendary cattleman Charles Goodnight. From the first moment I set foot here, I felt as though I had entered both a geologic monument to the passage of time and one of the few Texas locales that had managed to transcend it, unchanged by progress and development. Situated halfway between Amarillo and Lubbock, in a corner of the state not generally known for topographical attractions, it seemed like the perfect place to escape the city, to hike rugged trails through deep canyon fastnesses, and to sleep beneath brilliant stars normally obliterated by urban glare.

With much of the same sere, red-rock splendor as Big Bend or nearby Palo Duro — just without the crowds — Caprock Canyons is a relatively obscure state park most Texans have never heard of, including me until recently. From the Panhandle highways to the west, it’s pretty hard to see. There are no rising peaks. The interminable Staked Plains just suddenly terminate and fall away. But if you approach from the east, as I had earlier that morning, the edge of the caprock is a sheer wall rising abruptly out of the prairie grass. This park is composed of the boundary line where the erosion-resistant caliche of the High Plains tumbles into the lower Rolling Plains. At the transition between the two, the Little Red River and its tributaries downcut into the escarpment’s erodible fringe, creating scenic labyrinths of stone walls. As I forded the trickling river, I found it hard to imagine these thin ribbons of silty water accomplishing such an impressive feat of excavation. But when they flood, every grain of sand, every flint, is a cutting tool, widening and deepening the channel until millennia have passed and the gully has become a canyon with thousand-foot walls.

I broke camp a mile down on a flat-topped mound of sediment and shale in the badlands, hard against the cliffs. I spent much of the next morning scaling a switchbacking trail that ascended Haynes Ridge, the drainage divide between the Little Red River’s north and south prongs. The view from the overlook was sweeping: the canyon walls fingering off into scrub brush and broken hills that stretched to the eye’s limit. I pushed on across two-and-a-half miles of the ridge trail, through prairie grass and dense cedar brakes. On a stone ledge above a deep slot canyon, I ate peanut butter on a tortilla as I scanned the steep cliff sides for the mountain lions I could imagine prowling these slopes. Shortly after, I stumbled across the first horny toad I’d seen in years.

I descended the sun-soaked ridge and entered the misty shade of a grotto surrounded on all sides by enormous boulders. Water leaked from the fern-covered rock walls and pooled in small declivities. I sat on the cool sand, leaned back against a boulder, and enjoyed a siesta.

After an hour or so, the heat of the day was coming on, but so was dusk. I reluctantly left the grotto’s shade and followed a trail to the upper canyons. The temperatures pushed into the triple digits, and I was rapidly draining my water supply. I stopped off periodically in small pools of mesquite shade, sweat pouring down my back. Yet as miserable as the heat in the canyons could be, I couldn’t help but marvel at the exquisite layer cake of sedimentation and color in the cliff walls. There were bands of red shale, orange sandstone, thin stripes of limestone, most of it usually topped with a pale bed of hardened volcanic ash — each belonging to a long-gone geologic era. When I inspected them more closely, veins of gypsum filled the fractures between like frosting, and nearly as brittle. Atop the canyon walls, strange projections of stone, called hoodoos, often looked like silhouetted men surveying the canyon floor. This was an enchanted country, at once brutal and beautiful.

It was another three miles over rugged terrain before I slumped into camp, utterly wiped. I spent the remainder of the afternoon hiding from the sun in the meager shade of a squat juniper. At sunset: sweet relief. I lounged in a collapsible chair near my tent, drinking bourbon and watching the canyon walls flare tangerine, then rust, and finally purple as the sun sank behind the ridge. Coyotes began to emerge from their dens on a nearby hillside, and I could hear a litter of pups testing out their high-pitched yowls.

Nightfall brought a chill to the air. I laid down in my tent and looked up through the mesh at the Milky Way’s band arcing across the sky, as clear as I’d ever seen it. Toward midnight, the moon rose, bathing the pale badlands in its white glow. This was country the Apache had roamed, and after them, the Comanche. It had once been a part of Goodnight’s vast JA Ranch. It was nice to be reminded that not all of Texas was a city or a suburb. There were still wild places.

The next morning, I rose from my sleeping bag and boiled a cup of weak coffee. As I stood at the edge of my little hill, watching the light seep into the canyon, I heard a rustling in the nearby cedar brakes. What I presume was the same bison bull came ambling out of the brush, snuffling through the prairie grass patching a sandy arroyo. I felt relatively secure at my elevation, so I watched the animal for a while. His short tail switched idly. His shoulders and forelimbs were blanketed by a thick shag, which abruptly gave way to a sleek coat at his ribs. Occasionally he would kick at a biting fly on his flank with a hind leg. If he was aware of my presence, he didn’t much seem to care. He sauntered to within 10 feet of my hill when he suddenly lifted his ponderous head from the dry grass and studied me. He tossed his head and produced a deep chuffing sound, a warning no doubt. Then, having delivered his unmistakable message to me, he returned to his grazing.

I decided to break camp before the sun was too high and the canyon floor began to bake. I shouldered my pack, crept down the hill, and picked my way — quickly and quietly — through the brush, keeping one eye on the trail ahead, and the other on that buffalo.

Photography: Kenny Braun

From the July 2019 issue.