After a hiking partner’s injury dashed our planned trek through Big Bend National Park, opportunities to see the border region by mountain bike, horseback, zip-line, and small-engine plane more than made up for it.

I can’t say for certain that the coyotes woke me up. But I can say that when I stirred awake in my tent in Big Bend National Park at 4 a.m., the coyotes’ howling chilled me even more than the near-freezing temperatures.

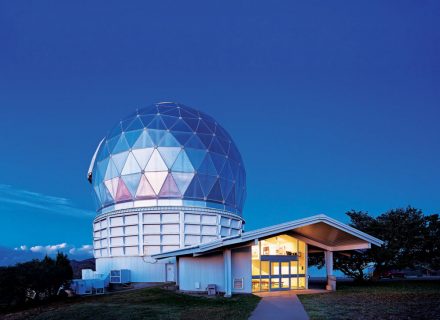

Their plaintive wails matched my mood. I had flown to Dallas and driven 560 miles to Big Bend to go on a hike I had been looking forward to for months. But one of my hiking partners injured his knee, and we had to cancel. That meant I had three days in southwestern Texas and nothing to fill them with except listening to coyotes and studying the Milky Way through the roof of my tent.

Those were incredible activities in the dark.

But what about in the light?

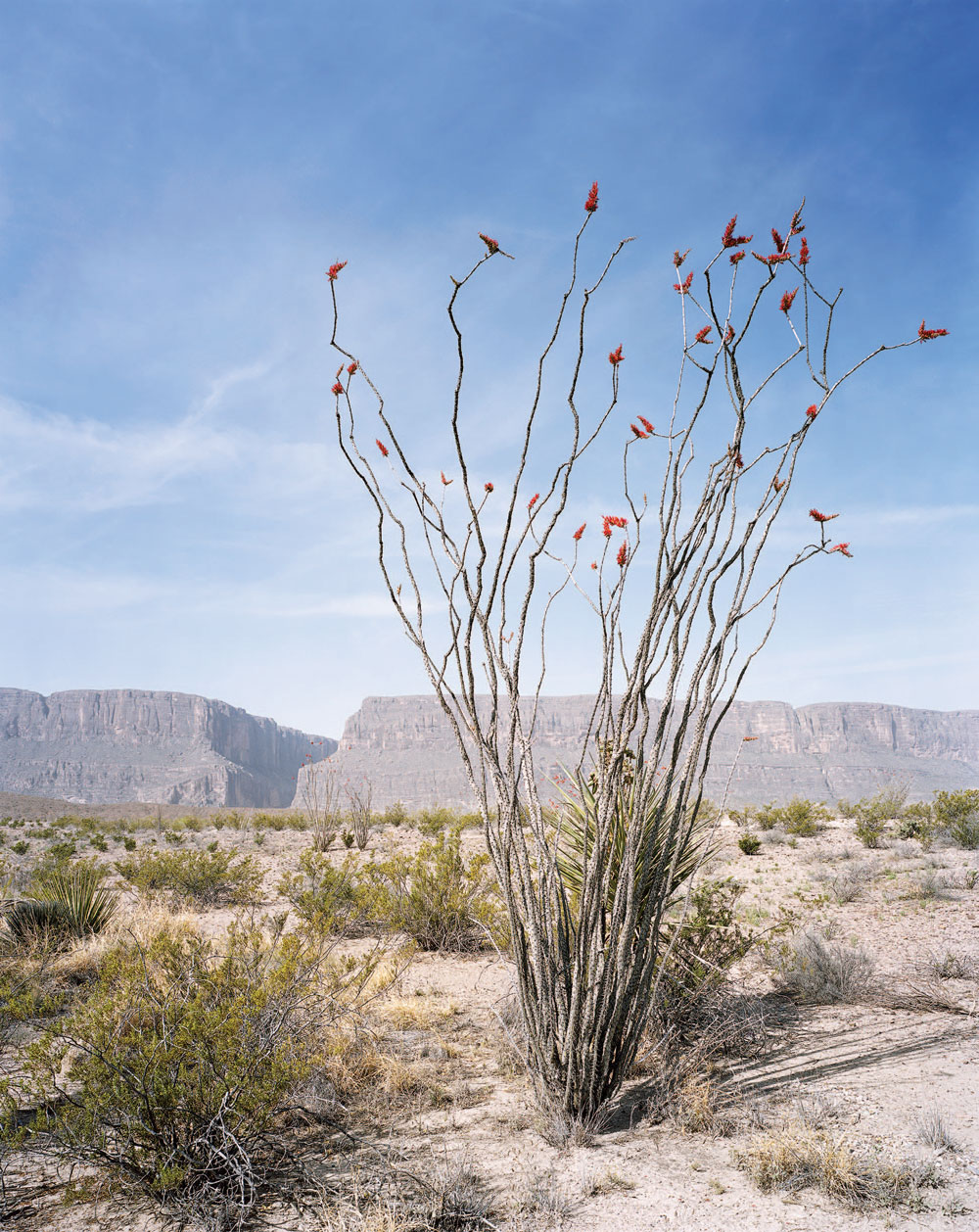

As the sun rose and the echoes of the coyotes faded, I decided I had come to Big Bend for adventure, and one way or the other, I was going to find it. Big Bend — a region in southwestern Texas bordered on the south by the Rio Grande and including the Davis and Chisos mountain ranges — covers millions of acres of rivers, creeks, deserts, mountains, ridges, canyons, and more. I vowed to see as much of it as I could, from as many different vantage points as I could, while going as fast as I could.

I started a wish list — mountain biking, horseback riding, zip-lining — and soon discovered that all of that and more was available within a few minutes’ drive of the national park. Whatever I wanted to do, I could do it, with the added bonus that costs were low and — when I was there, the first week of December — crowds were nonexistent.

“You should go up in a plane, see Big Bend from above,” a friend suggested when I told him of my open schedule and nascent plans to fill it. Not a bad idea. But I decided instead to first see the area from atop a mountain bike. I arrived at Desert Sports in Terlingua to rent one, and I knew I had come to the right place when I saw the “no walking on the grass” sign. There was no grass for hundreds of miles.

Owner Mike Long’s shaggy white beard contrasted with his skin, which looked to be as dry and cracked as the desert floor. I told him I planned to cram as much adventure into three days as I could, starting right here at this very moment in his very shop. He suggested I drive to the local airport and hire Marcos, the pilot, to fly me over the Big Bend region, making it twice in a few minutes that someone offered the suggestion.

I mumbled something about that being a good idea, but I wanted to see the desert from 6 feet above before I saw it from 6,000 feet above. I shelled out $40 and signed the waiver in case I crashed the bike. Long gave me patches for the tires, assuming I’d need them because I would run over cactus needles. (Now there’s something I never worried about as a boy riding my Huffy around suburban Detroit.) I loaded the bike into the back of my rented SUV and drove to Lajitas Trails, which, like Desert Sports and every other adventure business in this story, is on Highway 170.

The temperature was about 70 when I started and soon soared into the mid-80s. I rode into a canyon, turned left, and coasted atop rock as smooth as a countertop. My tires slipped off that and bogged down in squishy sand. After two hours in which I saw zero other humans, I embarked for one final lap of Brennecke Loop, 5.5 miles of soft sand, jagged rocks, and razor-sharp cacti. The wind whistled against my body and doubled my work. I could see my car in the distance, and for 20 minutes it seemed like no matter how hard I pedaled, I didn’t get any closer. I panted and heaved, sucking in dust, which made me pant and heave even more.

Just when I started to wonder if the last lap was a mistake, I found respite from the wind behind a ridge and finally returned to my car. When I dropped the bike off at Desert Sports, Mike was gone but a clerk seemed surprised I hadn’t gotten a flat, and she asked if I had crashed. Nope, and thank goodness. Of all the vantage points from which I wanted to see Big Bend, face-first was last.

I pulled out of Desert Sports and steered the SUV through Big Bend National Park. I drove that road 10 times, and it looked different every trip because some new and beautiful part of the landscape distracted me. My phone rang — the only time all week it did that, because cellular coverage was scarce. It was C&I editorial director Dana Joseph checking in to see how my adventures were going.

“You should go up in a plane,” she said. Here we go again, I thought. “The pilot’s a great guy named Marcos,” she said. Yeah, I know. “Let me see what I can arrange,” she said.

I called Marcos and scheduled to go up with him two days later.

The next morning, I drove back through Big Bend National Park to Big Bend Ranch State Park, where I planned to camp that night. I told the rangers I was excited to see this beautiful region from above.

“Are you going up with Marcos?” asked one.

“He’s a great guy,” said the other.

By now I couldn’t wait to meet Marcos.

But first, I had a date with Geronimo at Lajitas Stables, just down Highway 170 from Desert Sports. Geronimo is part quarter horse, part Percheron, brown, beautiful, and, if I’m being honest, lazy. Every few minutes he wanted to stop to eat. I yanked on the reins as often as I could to dissuade him, but he was sneaky about it, always managing to duck his head down at the precise second I had spun to look at the mountains around me. As often as Geronimo wanted to stuff his face, he wasn’t as bad as Sophie, the horse in front of me. She ate more than she walked, and she walked for miles.

We traversed a trail that climbed roughly 500 feet into the desert mountains. Behind me, the Rio Grande slithered like a lime green snake through brown dust. Ahead of me a ridge stood in relief against the sky like a couch traced against a wall. I could not see land on the other side of the ridge, so it looked like we were walking toward the end of the world. The blue sky beyond the ridge was deep and rich and so full of texture that it appeared to have substance. It looked like if I smacked Geronimo on his rump and we ran and jumped off the ridge, we would sploosh into a wall of Jell-O.

Which Geronimo would have eaten, unless Sophie ate it all first.

We meandered away from that ridge and stopped to eat in Lunchbox Canyon, or at least that’s what the stable guides call it, because it’s a box canyon where they take customers for lunch. Our guide, Janelle, pulled out chicken and fruit and rice and salad and desserts and drinks, and we feasted in the most epic food court I’ve ever seen. Walls climbed straight up on three sides, and the path we took to get there turned, so even though we were in the desert, surrounded by vast stretches of nothing, I felt almost hemmed in. I explored on foot, walking in and out of sun and shadow and in and out of warm and cold. The sky, still thick and blue, looked far away now, so tall were the walls around me.

I turned a corner and could no longer see the horses or people who had been riding them. My phone didn’t work, there were no planes, no sounds of the highway. I felt like I had walked away from life, and it was only reluctantly that I walked back.

I climbed back on Geronimo and returned to the stable. I told Janelle about my plans to go zip-lining that afternoon and to go up in a plane the next day.

I didn’t say with whom.

I didn’t have to.

“You’re going to love Marcos,” she said.

The good news about zip-lining is the sensation of the speed is a blast. I felt it most vividly in my eyes, which dried out like the ground below me as I zoomed over a canyon at 50 mph. The bad news is you can’t go fast forever. A braking contraption sits atop the line at the bottom of each run, and when you hit it, you stop, immediately. On the first run, I did not lean back far enough and hit my head, hard, on the contraption. I was so startled that I checked my helmet to make sure the impact didn’t break it. I was surprised it suffered no damage.

On subsequent runs, I leaned back far enough that I didn’t hit my head. But the brakes still jolted me enough that I must mention them here. For what it’s worth: I went zip-lining in West Virginia a few years ago, where the braking system required me to use my hand to stop myself, and I didn’t like that either. It’s possible I’m just a whiny baby about zip-lining brakes.

I woke up with a start in my tent, jolted out of a fitful sleep by what appeared to be a flashlight shining into it. My campsite was secluded, down a hill, through a thicket of trees and just a few feet from the Rio Grande. The light could not be there by accident.

Whoever was doing this was doing it on purpose, I thought. It freaked me out: There was only one other person in the campground. He had seemed friendly enough when I met him a few hours earlier, had in fact given me as much firewood as I could carry from his site. Maybe he was too nice, lulling me into being comfortable so he could ... I didn’t want to finish that thought.

I could think of no good reason why he would be shining a flashlight into my tent, and in my half-asleep confusion, I could think of many bad ones. I did not want my adventure in Big Bend to include fighting an ax murderer.

I bolted upright and brushed my head against the ceiling of my tent. That slight contact hit me like a shot of espresso, bringing my dulled thinking into sharp focus. Only then did I realize that the light was not from the flashlight of a psycho camper but the headlight of a car across the river, across the Rio Grande, across the border in Mexico.

I drove to the airport and met Marcos — Marcos Paredes, owner of Rio Aviation — and within 30 seconds I stopped wondering why everyone and their brother had said I needed to fly with Marcos. He promised my hiking friends and I the “AAA” treatment, meaning we would be amazed (check), airborne (check), and amused (check).

He managed to be charming and funny even while talking about safety precautions aboard his plane. He said that if we dropped anything, it could roll into the front of the plane and get caught in the gears, so we should be sure to secure cell phones and water bottles and bowling pins and authentic autographed Houston Astros baseballs.

We climbed into “Ol Brownie,” as he calls his Cessna 205, and it reminded me of station wagons of my youth. When Marcos fired up that old bird, my seat shook. Marcos steered us down the dirt runway — a first for me — and lifted off, just south of due east, into the clear morning sky.

I tried to balance listening to Marcos, gaping at the vast and varied topography below us, and scribbling down Marcos’ running commentary. My “questions” consisted mostly of “That’s beautiful” and “Wow!” and “Does it ever get old flying over this?”

Marcos knows the region probably better than anybody, and his answer to that last one is still no. We soared for an hour and a half over what used to be an ocean floor. We saw mountains and deserts and deep canyons sliced out of the ground like a butcher knife through a watermelon. We flew over the Rio Grande, which Marcos patrolled for 30 years, and a baseball field, which he helped build, and even his house, where he has lived off the grid for decades.

Marcos moved here 40 years ago, and he stayed because it’s beautiful but also because he realized that however old Big Bend is, it is also still being created, and he has had a hand in much of what is there now, including his service on the boards of the Big Bend Education Corporation and the Emergency Services District.

As we pulled in for final approach, it occurred to me that I had seen Big Bend from a bike, a horse, and a zip-line, and none of them matched the view Marcos gave me. To see it inch by inch on a bike, horse, and zip-line was breathtaking enough. To see it all at once from the seat of Marcos’ Cessna was to be stunned into reverence. The whole was even better than the parts, and the parts were spectacular.

As the ground rose to greet us, Marcos gently wrestled with the controls to keep his speed steady and his wings even. No bowling pins or autographed baseballs made his job any harder than it had to be. He said with mock pride that so far in his flying career, he had exactly as many takeoffs (3,940-something) as touchdowns, and he sure hoped to keep it that way. My adventure was ending, and Marcos stuck the landing.

Photography (From top): Alex Burke, Courtesy National Park Service, Courtesy National Park Service, Alex Burke

From the July 2019 issue.