The beloved author built a career on western stories. Now his son is reviving L’Amour’s unreleased works beyond the genre.

For fans of classic western storytelling, there are singular talents whose names have become practically synonymous with the genre. What John Wayne is to acting, what John Ford is to directing, what Gene Autry is to singing, Charles M. Russell to painting, and Frederic Remington to sculpture, Louis L’Amour is to the western novel.

L’Amour was famously prolific, with nearly 100 novels and hundreds more short stories, poems, screenplays, and articles published. Even so, he left behind stacks upon stacks of unfinished and unpublished works. Since L’Amour’s death in 1988, his son, Beau L’Amour, has dedicated much of his adult life to managing his father’s literary estate. Beau’s work, which began during his dad’s lifetime and with his permission, has included editing manuscripts L’Amour left behind. It has also involved writing and directing audio adaptations, writing and producing film scripts based on his father’s works, and editing L’Amour’s final work of fiction, The Haunted Mesa.

Now, Beau is overseeing the Lost Treasures series, which so far includes the publication of two volumes of short stories (many left unfinished), television treatments, early drafts, and other unreleased projects. The series also includes postscripts to existing books that Beau calls “bonus features,” as well as online content for readers looking to take a deep dive into L’Amour’s life through photos, notes, and fragments of stories that didn’t make it into Louis L’Amour’s Lost Treasures Volume 1 (published by Bantam Books in October 2017) or Volume 2 (planned for a 2019 release).

Perhaps most intriguing, Lost Treasures includes No Traveller Returns, L’Amour’s earliest attempt at a novel-length work. Beau fleshed out and completed the book L’Amour began working on in 1938. It’s set for release 80 years later, in October 2018, by Bantam Books. An ambitious adventure set on a westbound tanker ship carrying a dangerous cargo and a volatile mix of personalities, it’s based on L’Amour’s experiences as a merchant seaman.

It’s also the first Louis L’Amour project on which Beau considers himself not just an editor but also a co-author. He describes the manuscript he found as “a pile of chapters,” with hints at a couple of different endings that weren’t fleshed out. Beau worked on every page. Still, even as a co-writer, he stuck by his self-imposed rules for working with his late father’s incomplete writings. These guidelines have served him since the L’Amour estate first started putting out previously unpublished short stories.

“I will not finish something,” Beau says. “I’m not making this a permanent promise for myself, but the guideline has always been, up to now, I won’t finish something unless I understand what his idea for the trajectory was supposed to be.”

That’s why many of the stories in the Lost Treasures volumes are left unfinished, though, in a postscript, Beau will point out where he thinks a story was going.

“In the case of No Traveller Returns, I was very clear on what he wanted to do with it,” he says. “It was just a wonderful opportunity.”

No Traveller Returns is a glimpse at a trajectory L’Amour’s career might have taken had he continued to develop as a literary fiction writer. Instead, the postwar demand for tales set in the Old West and L’Amour’s ability to crank them out offered a solution to his financial struggles.

“Dad started writing adventure stories, sort of exotic, high-adventure, international-adventure stories,” Beau says. “He wrote some of those that were very personal and realistic.” As an example, Beau points to stories like those in Yondering, a 1980 collection of adventure yarns based on L’Amour’s own experiences. “The last of those will be [No Traveller Returns]. And he wrote a lot that were considerably pulpier. Those definitely had an Indiana Jones kind of flavor to them.”

But after World War II, the market for those kinds of tales vanished.

“Before World War II,” Beau says, “very few people had traveled to other places. Other places on earth were very exotic and fascinating. After the war, I think a lot of times people thought, Well, my son died there. I don’t want to read about that.”

L’Amour had only sold two or three westerns at that point, but, Beau says, he may have sensed that the market was headed toward westerns, and an editor explicitly told him at a New Year’s Eve party in 1946: Write westerns.

“I think the attitude was [that westerns] were comfortably at home and comfortably in the past,” Beau says. “They were an adventure-style story that wasn’t as jarring to an audience as the prewar pulp adventures had been.”

L’Amour wrote a story called “The Gift of Cochise,” which was bought by Collier’s and optioned by John Wayne and Robert Fellows. Emboldened by the sale but also still in need of money, he flew to New York and barged into every editor’s office he could find to proclaim himself their new western writer.

It worked. L’Amour made four sales and garnered ongoing commitments with two publishing companies.

“The Gift of Cochise” would be adapted for the screen as Hondo in 1953. L’Amour’s life would never be the same.

“He just turned his life around by very forcefully getting behind this movie,” Beau says. “He sold himself as the western guy, because he had this big western movie coming out. He didn’t really see himself as being that for the rest of his life. It was just something that was working at a time when he was in desperate trouble.”

Several decades and millions of book sales later, L’Amour eventually and carefully steered his career to a point where he could sell titles like The Walking Drum and Last of the Breed, novels that are decidedly not westerns. Toward the end of the 1950s, though, when L’Amour first tried branching out into other genres, nobody was interested, Beau says. Much of the material from Lost Treasures comes from this time period, when L’Amour envisioned for himself a literary life outside the Old West.

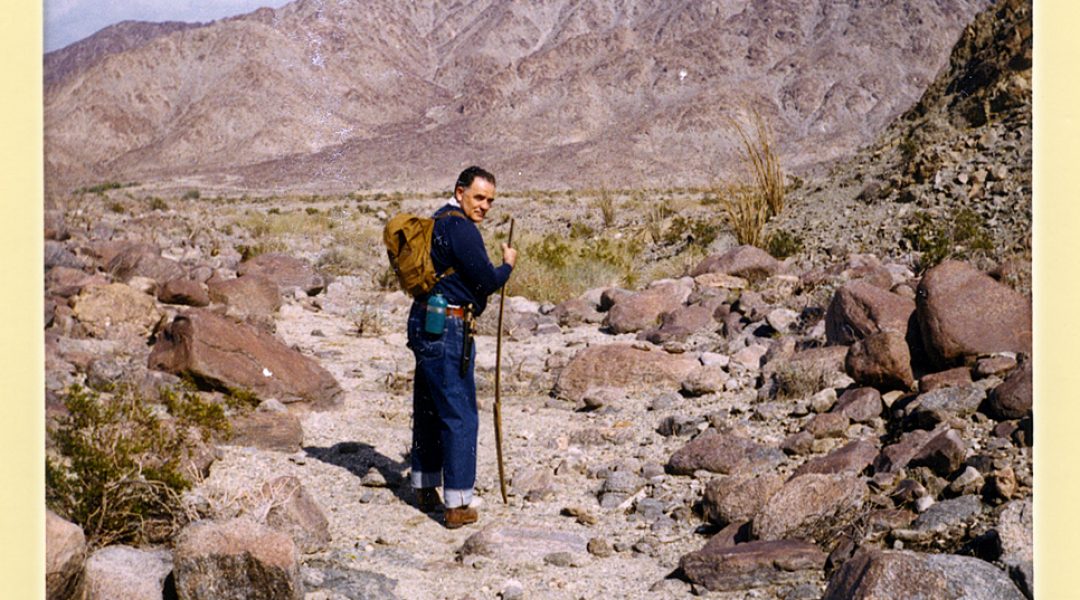

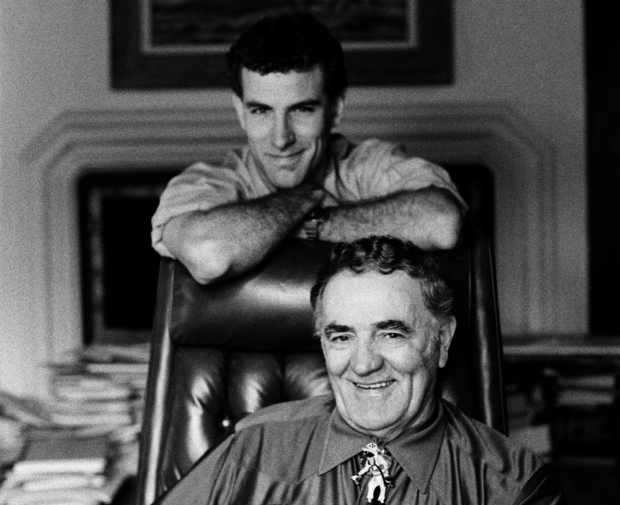

Photography: (From top) Louis L’Amour hiking near La Quinta, California, in the 1960s; Beau and Louis L’Amour in the author’s office in West Los Angeles. All images courtesy the Louis D. and Katherine E. L’Amour Trust.

From the May/June 2018 issue.

More About Louis L’Amour

Today’s Western Writers on Louis L’Amour’s Influence

Louis L’Amour’s Law of the Desert Born Goes Graphic