Eighteen years ago, fine art photographer E. Dan Klepper committed to something he’d long dreamed about: He moved to remote Marathon, Texas, 50 miles north of Big Bend National Park. There, he built a gallery and a studio — and a life.

He’d been around enough to know where he really wanted to put down stakes. Born and raised in San Antonio, E. Dan Klepper got his master’s at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and then bounced around working in Chicago, New York, Houston, and West Texas. The rugged backcountry of the Lone Star State captivated Klepper — he knew he eventually wanted to make his way back to where nature, not man, predominates.

“The natural world is probably my most consistent source of inspiration,” Klepper says. “It’s why I’ve chosen to live in the Big Bend. Nature is beautiful and scary and weird and uncontrollable. It’s total chaos, and all we can do is either submit to it or attempt to decipher a little enlightenment out of it.”

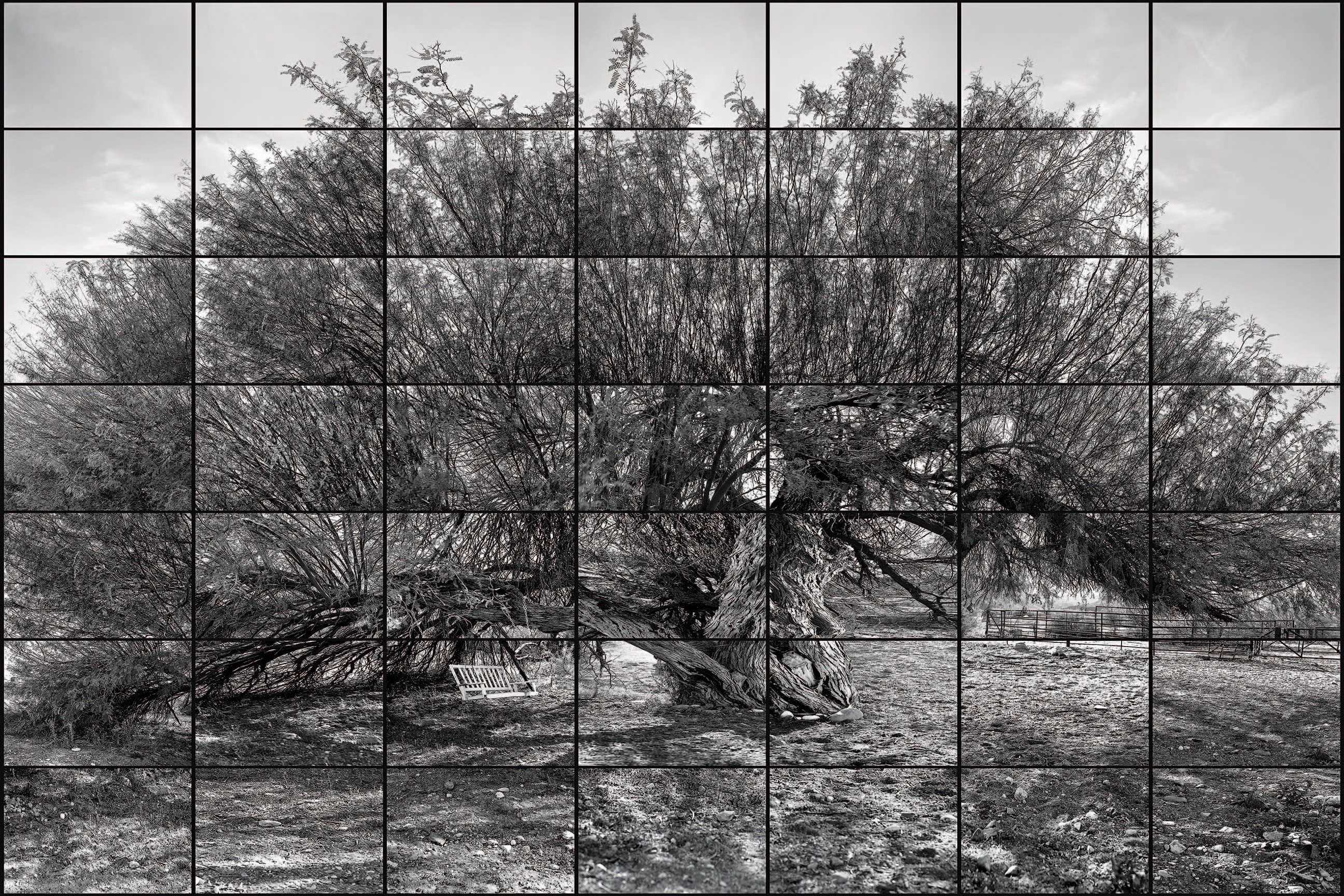

Klepper deciphers and documents all kinds of enlightenment in many mediums, including in his recent book, Why the Raven Calls the Canyon, an exploration in images and essays of eight years spent helping to rehabilitate Fresno Ranch in Big Bend country.

We talked with Klepper about finding art, inspiration, and beauty in the middle of nowhere.

Cowboys & Indians: You’re a bit of a Renaissance man. You lived rough in Big Bend and know the life of the calloused hand. On the other hand, you make videos, sculptural works, and fine-art photographs. What made you pick up a camera?

E. Dan Klepper: My father was a journalist for the San Antonio Express-News, writing and photographing stories about the Texas outdoors for 40-plus years before passing away in the early ’90s. As a result, I learned to think about photography as a profession rather than just a hobby. Photography meant work, not fun; a means to an end rather than an end unto itself. It didn’t stop me from working in the medium, but I probably took the long way around in making it my work of art.

I received a used Minolta 35-mm SLR from my father when I was 14 years old. I think I wore that Minolta out. Tri-X black-and-white film was cheap, especially because I processed and printed my own film in a backyard shed. Every picture I shot back then was pretty lousy. I really didn’t shoot a good picture until I was about 19. I snagged a summer job photographing rural communities located around a region of North Texas slated to become a reservoir. The job, a tiny part of a very large academic study, didn’t pay much, but it was the first time I could afford to shoot in color along with black-and-white. I photographed everything that summer: friends, goat farmers, tobacco-spitting contests, as well as stretches of rolling grasslands that today lie beneath 100 feet of water.

I loved exploring the North Texas countryside during the years I lived there, but I did so with a revised understanding that summer, realizing that the landscapes I captured would change or disappear altogether. But what I failed to realize at the time was that, reservoir or not, nothing I saw during those years would remain the same. It was the hubris of youth, I guess, a naive assumption that everything around me would be my own again, a limitless access to the inspiration of my days.

C&I: What led to your decision to move to Marathon? What keeps you there?

Klepper: The year 1992, before I moved back to Texas, was a tough one. I had to make a lot of difficult personal decisions that year. But I also determined that once I traveled through my wormhole of turmoil and came out the other side, I wanted to be in a place that inspired me every single day. I didn’t care how long it took to get there (it took eight years). I wanted to step outside and see the planet in all its charisma and calamity every single morning that I opened my eyes. The Big Bend delivers that for me.

C&I: What things tend to compel you visually?

Klepper: If I see something that strikes me — a simple gesture, some weather phenomena, the way animals appear to communicate — a story around it will start to form in my head. I’m on the trail a lot, hiking, and occasionally I’ll see something that just strikes me dumb. I’ll stand and watch it, forgetting about my camera and everything else. A dust devil is like that — all fury and physics. Take your eyes away for a second and it vanishes.

I’m always trying to determine the point at which I stop just looking at something and start actually seeing it. I can usually track the process technically — got the light right, in focus, eliminated unwanted elements in the composition — but drilling down to the visual essence of the thing is tricky. It’s subjective for both the photographer and the viewer. You’ve got to feel it.

C&I: How do you know when you’ve got an image that really works?

Klepper: If I can go back to an image again and again and still feel it in my gut, then I know I made it work, at least for myself.

Thanks to smartphones and social media, photography now plays a routine part of people’s lives. Today, everyone’s a photographer, taking and posting photographs of “real” life. But photography still has this remarkable ability to challenge our reality in ways that other mediums, including film, don’t always seem to be able to do. With photography you can capture moments inherently loaded with a story, inseparable from the moment’s past and future because, well, you’ve captured a moment in time. Films spell the story out for you in continuous moments, leading you to the filmmaker’s personal conclusion or question, and that makes filmmaking a passive art form.

But with photography you get just a glimpse of the artist’s perception, and if the artist gets it right, that single glimpse will tell a complete story customized by the viewer’s own worldview, allowing photography to be a participatory art form. Your single moment becomes a part of many larger stories, making photography a clairvoyant, magical time travel in this beautiful, creepy kind of way.

C&I: What’s your creative process for achieving that clairvoyant, magical time travel?

Klepper: I like to tell stories. That’s probably why I’ve made a living from writing as much as from making art. Stories always start with a question. Who is this character? What happened here? How is this possible? When I start a series of images, I pose my own question. For example, the collection of images and essays in my recent book, Why the Raven Calls the Canyon, came about after spending some time along a Rio Grande River canyon in the Big Bend region of Texas. Every afternoon, ravens would strafe the canyon corridor, gliding above the river, and their calls would echo off the canyon walls. Birds have pretty decisive reasons for the sounds and songs they make and ravens are smart birds, perhaps among the most intelligent, so I wondered what their calls meant. But the more I observed them, the more I realized how little I knew about them and their calls. As time passed, the question took on a more metaphysical character, which I tried to puzzle out with the book. The simple answer? Because they can.

C&I: Pretty different from most people’s daily experience. Is there such a thing as a typical day of being a fine artist in Far West Texas?

Klepper: I can’t really say what it’s like for any other artist, but there are some characteristics that we all share. Living here is a bit like a 19th-century existence with some of the 21st century tossed into the mix. We are a long way from some things a lot of people take for granted (superstores, major airports, surgery), but we get high-speed internet and, in trauma emergencies, airlifted by helicopter. I see real cowboys wearing spurs just about every day, but when they stop in town for a six-pack they also check their text messages. We get electricity, of course, but a winter ice storm will snap cross bars, wiping out miles of the grid, leaving us without power for days. We have cell service except when lightning strikes the tower and knocks it out. Then the only people who can talk on the phone are those who still have old, scratchy landlines. I must travel 30 miles to get a suit dry-cleaned or a haircut, but I can then drive another 20 minutes to Marfa and see art or performances on par with those found in most major cities.

C&I: What makes Texas (and the West) particularly photogenic?

Klepper: I think people love West Texas for the way it seems to cast any subject set down into it as a touchstone. The singularity of the place doesn’t feel condensed into a “style” — yet. The light and horizon, clean and unobstructed with simple lines of unambitious mountains, isolate and enhance things like the “vignette” effect on your smartphone. Traveling through the landscape makes you feel more gypsy than tourist, deciding your next move by nothing more than the lengthening of shadows through the day. It’s a wayfarer’s dream.

C&I: Is it that dream you’re hoping to communicate with your art?

Klepper: If nothing else, I hope my art promotes a deeper appreciation for the planet’s wildness. And I’d like the work to be seductive. I believe the idea of beauty is often underrated and want aspects of my work to express beauty, if only to explore how the most beautiful things in the natural world can also disguise its darkest forces.

Visit Klepper Out West

Built more than 100 years ago out of 16-inch adobe blocks, the building that houses Klepper Gallery in Marathon, Texas, was originally constructed as a warehouse for a dry goods store. Today, Klepper says, with “basic additions like electricity, windows, and plumbing,” it serves as his showcase as well as his studio in “a very sparse community of about 400 people,” where the nearest town is about 30 miles west.

“It doesn’t seem like a very good place for a gallery,” Klepper says, “but, as the gateway to Big Bend National Park and parts west like Marfa, up to about a half million people or so come through each year. ... And it’s only 50 miles from Big Bend National Park.” If not in Marathon, visit Klepper online at edanklepper.com.

Dan Klepper is represented by William Reaves | Sarah Foltz Fine Art in Houston. His work will be on view at the gallery during Houston’s Fotofest Biennial March 10 – April 22. reavesart.com, fotofest.org

From the February/March 2018 issue.