In the midst of a war fought on land that once was theirs, over a nation that denied them citizenship, Native Americans found themselves faced with a dubious decision: Whose side should they be fighting for?

In 1861 it seemed that America was coming apart. Secession, Confederate nationhood, the firing on Fort Sumter, and a mesmeric rush to combat engulfed the nation. The realities of the crisis differed for everyone as individuals examined family, community, state, and national allegiances. One hundred and fifty years after the cataclysm of the American Civil War, we still tend to think of it in terms of black-and-white: the majority white soldiers and civilians, the minority African-American slaves. But what of the indigenous peoples of America?

For many American Indians, the impending conflict created no less of a crisis than it did for the dominant society. But their experience would be primarily defined by their location in the country. Geography was everything. As the tide of non-Indian settlement swept from East to West, indigenous people became minorities within settled regions. They remained Native, but adapted various political, economic, and cultural aspects of their lives to better coexist with their new neighbors. By the time the Civil War started, Indians in settled regions experienced the conflict as members of larger communities whose movements they did not control. Indians living on the edge of incorporated states were better able to retain tribal autonomy, yet they were still strongly influenced by national and state political discourse. Those groups well beyond the white frontier in “Indian Country,” however, generally lived with little concern for U.S. politics.

As the nation became consumed by war, few Anglos on either side of the Great Divide considered the Native Americans living among them. East of the Mississippi, tribal lands had been so diminished that most of the 30,000 Indians in the Union did not live in powerful tribal units. Thus, as the country headed for dissolution, Eastern Indians were left to make individual choices about whether or not to engage in the conflict. The Indian minority was concerned less about the divisive issues of slavery and the preservation of the American Constitution than about their ongoing struggle to hold on to their remaining land and culture. If fighting for the Union cause brought the respect and perhaps gratitude of those in power, then it was a means to an end. Army service also brought regular pay and food, adventure, and the continuation of an honorable tradition of Native warriors.

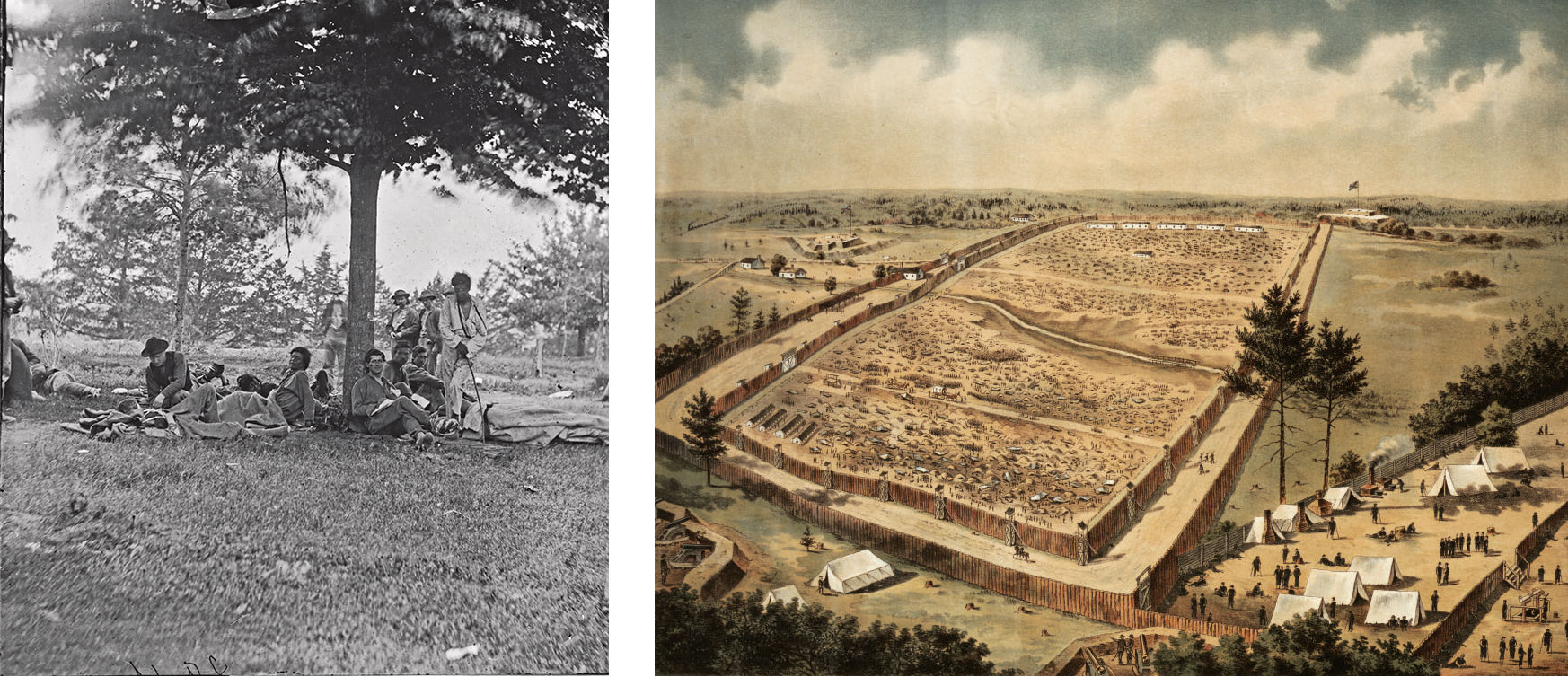

Indians all over the North took up arms for the Union cause. Company K of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters enlisted more than 150 Ottawa, Chippewa, Delaware, Huron, Oneida, and Potawatomi Indians. Sharpshooters received extra training, enjoyed high morale, and used their Sharps breechloaders to devastating effect. But they also experienced discrimination. Fellow soldiers often made uncomplimentary remarks, generally sticking to well-worn stereotypes of “desperate” or drunken men. Yet the Indian sharpshooters proved themselves time and time again in the grueling Virginia battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Petersburg. After the ill-fated Battle of the Crater during the seige of Petersburg, survivors recounted how a group of mortally wounded Indian soldiers chanted a traditional death song before finally succumbing, inspiring others with their valor.

Native Americans living on the ever-shifting Western frontier confronted a different situation. Most Indian nations on the periphery of the organized states sought to avoid involvement in national issues that did not seem to affect their lives. However, neutrality was not an option for those in strategic locations. Indeed, recently settled areas just west of the Mississippi would bear the full brunt of the conflict. Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) lay directly between Confederate and Union territory. Both the United States and the Confederacy eventually realized that this important buffer area between Kansas, Arkansas, and Texas would play a critical role in the war. But before the national governments organized diplomatic missions, citizens in states adjoining Indian Territory clamored for Indian involvement. They were determined to recruit the thousands of Native people on their borders for their side in the war. Arkansas offered weapons, while Texas readied men to occupy former federal forts. The Native nations found themselves facing mounting pressure to take sides.

The Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations could still be considered newcomers in Indian Territory in 1861, having arrived there at the end of the arduous journey known to history as Indian Removal two decades before. They were still putting their societies back together when the war came. Native leaders consumed with economic progress, political infighting, and societal disarray now had to choose sides in the conflict dividing the larger nation. The choice was not an easy one as the federal government provided the annuities owed to the nations for surrendering land in the East, while tribal members had strong economic, social, and religious ties to the surrounding Southern culture.

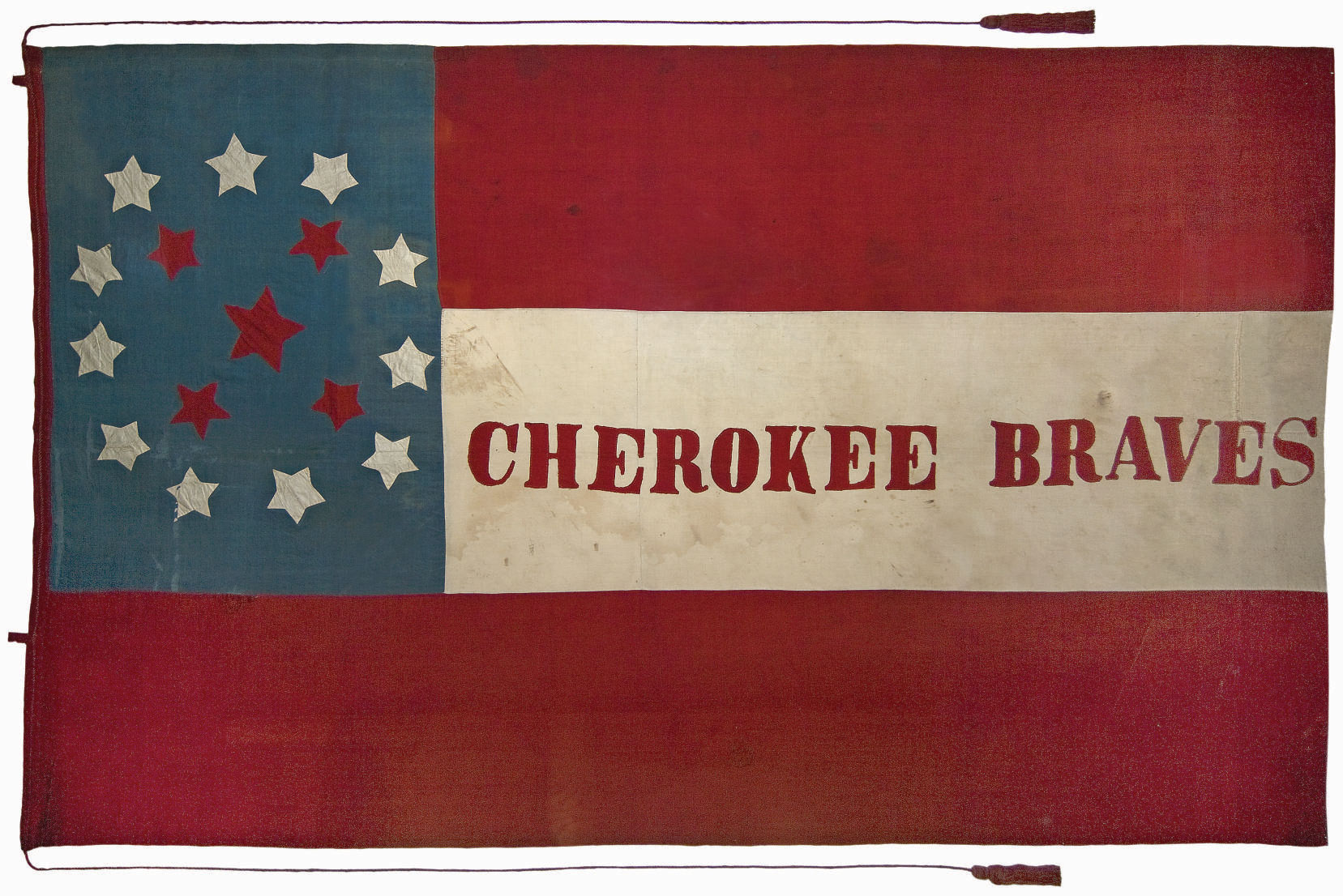

Each of the five southeastern Indian nations decided independently which side to support, and each chose the Confederacy. The United States’ complete disengagement with the region and the Confederacy’s proactive diplomatic overtures helped to sway the Indian leaders. The Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations all signed treaties of alliance with the Confederate States of America in 1861. Official lines were drawn, but the outcome was far from simple.

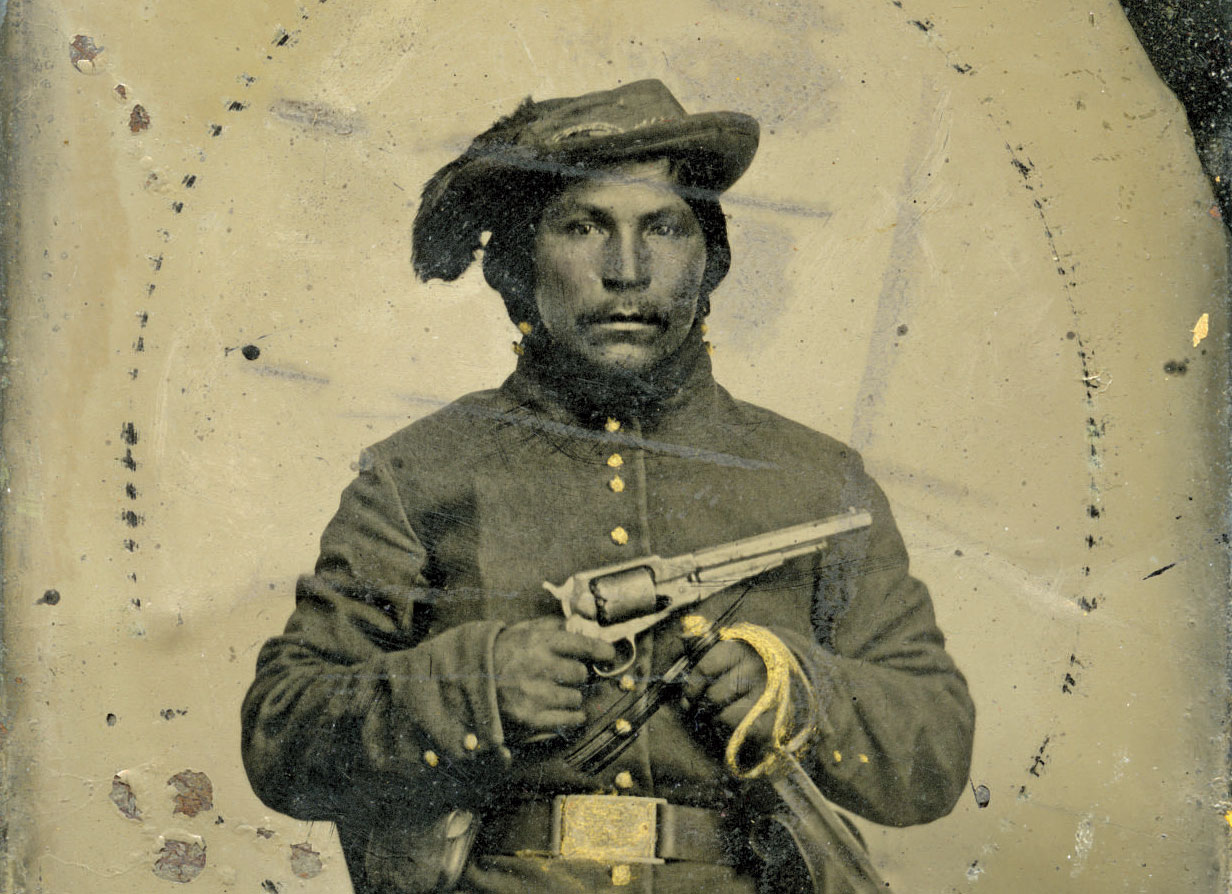

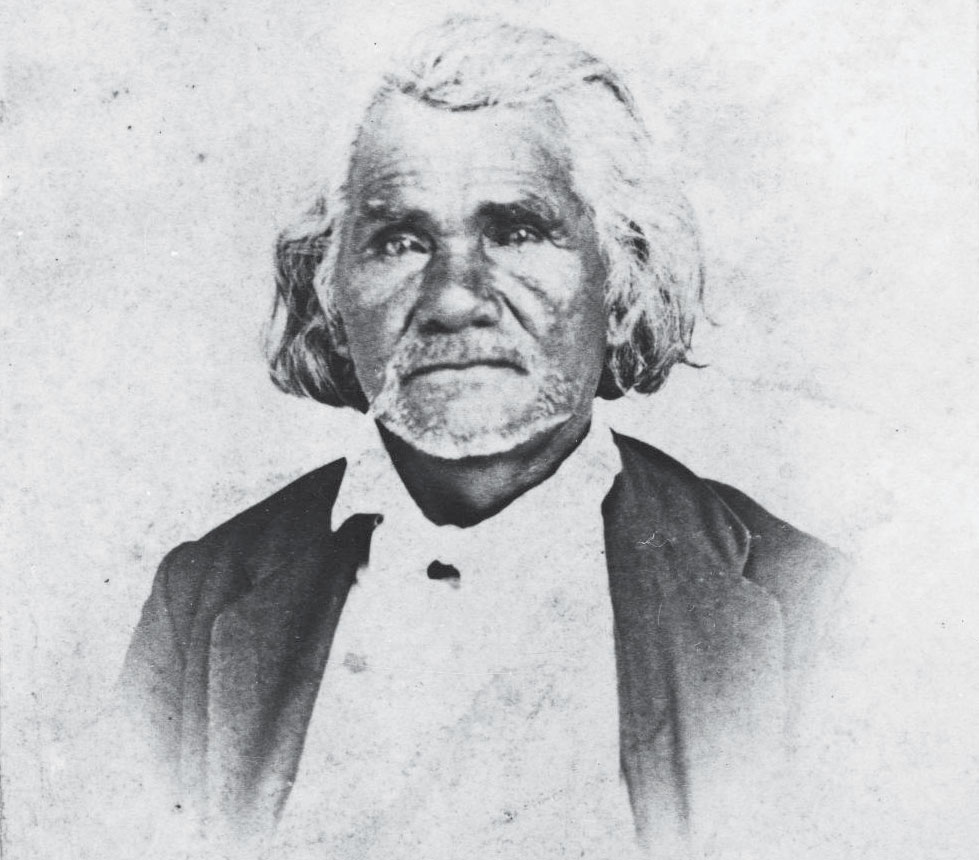

Native soldiers were mustered into Confederate units comprised of their own members — including officers, a privilege the Union never afforded to either Indians or African-Americans in its service. At least one of the Indian officers, Cherokee Brig. Gen. Stand Watie, rose to prominence and is remembered as the highest-ranking Indian in the Confederate army.

Military service quickly became complicated for the Cherokees as they were ordered to attack neighboring Creeks loyal to the Union. This demand, which ran counter to ideas of Native kinship and values, caused unrest among Cherokee troops, and many left Confederate service. Soon their chief, John Ross, took advantage of the belated arrival of Union support in the territory and pledged his allegiance to the United States for the remainder of the war. The Cherokees were now sending men to don both blue and gray, causing an internal civil war within their nation.

The loyal Creeks suffered terribly as refugees in Kansas territory, awaiting federal support to allow them to return home unmolested by their Confederate kin. Seminoles, too, were split by mid-war and fought for both sides. However, the Choctaw and Chickasaw entered the war more united politically. Because they were heavily engaged in a slave-based, cash crop market economy, these two nations decided for Southern allegiance and remained committed.

Fighting raged in Indian Territory for most of the war. Regular troops from both armies, as well as countless guerrillas and raiders, swept back and forth through the region. Except for a few notable battles, like Honey Springs in July 1863, most of the fighting was characterized by skirmishes and raids. These small but destructive engagements took a terrible toll on soldiers and civilians. Homes and businesses burned, farmland lay fallow, mills ceased operation, livestock disappeared. Poverty, disease, and dislocation threatened to destroy Native society. The region suffered both military engagements and enemy occupation unlike any area of the Union and most of the Confederacy.

As the federal government became consumed with war, Indian relations fell off the radar screen in Washington. But on the Western fringe, the drumbeat of nationalism combined with the lack of federal oversight created a perfect storm for the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho people.

In 1862, Colorado was still a territory with a new and ambitious governor, John Evans. A railroad and real estate investor, Evans presided over a territory facing increasing tensions between white settlers and Plains Indian tribes. Evans began to fear that the tribes were uniting and amassing arms as troops were being pulled out of Colorado to fight in the Civil War, so in the summer of 1864 he obtained authorization from President Lincoln to temporarily form the 3rd Colorado Infantry for the sole purpose of fighting “hostile” Indians.

Commanded by Methodist minister Col. John Chivington, the 3rd Colorado found itself with no one to fight after chiefs Black Kettle and White Antelope met with Evans and Chivington in Denver and accepted the governor’s entreaty to make peace. The chiefs agreed to bring any Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians who didn’t want to fight to Fort Lyon for protection, where they camped nearby alongside Big Sandy Creek.

But when Evans left for Washington to personally advocate for statehood, Chivington created his own conflict. On November 29, 1864, Chivington led his men in a surprise attack on the encampment of 500 Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians. This was an Indian village — not a raiding party — and at daybreak the still sleepy community was entirely unprepared for attack.

Surviving witnesses described the morning as a frenzied bloodlust of torture and killing. Seven hundred troops of the 1st and 3rd Colorado Cavalries committed atrocities upon 500 Cheyenne and Arapaho, most of whom were unarmed women and children, leaving 160 to 200 dead and many more raped and severely injured. Congressional investigations into the Sand Creek Massacre revealed that Chivington launched the gruesome attack without authorization and found that he should be removed from office and punished, but no charges were ever brought. In response, many Cheyenne and Arapaho joined the militaristic Dog Soldiers, seeking revenge on settlers throughout the southern Plains.

For many Native Americans, the irony of the Civil War was that they were inexorably involved, whether they chose to take sides or not. The repercussions of the enormous conflict entangled Native peoples living both within and without the borders of the Union and Confederate states. Not desired as participants at the start, their value as recruits grew as the war dragged on, as more and more white men died. By the end, a Native American — Ely S. Parker — would stand side by side with Ulysses S. Grant for the signing of the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House, forever immortalized in that historic moment. But military involvement, whether sought or forced, did not substantially benefit Native peoples. Instead, the war of brother against brother, tribe against tribe, would cost them a great deal.

Dr. Clarissa W. Confer is an assistant professor of history at California University of Pennsylvania and the author of The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War (University of Oklahoma Press, 2007) and Daily Life During the Indian Wars (Greenwood, 2010).

From the January 2012 issue.