Ledger art helped Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche, and Caddo warriors imprisoned at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, survive — and even thrive.

“I had never seen a more pitifully demoralized group than the travel-weary warriors who clutched ragged blankets about them,” the poet Sidney Lanier said as he watched some 70 Southern Plains warriors in leg-irons in St. Augustine, Florida. The prisoners’ journey from Fort Sill in the Indian Territory had taken 26 days from wagons, to train, to steamship, and finally oxcart. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s army fought the five tribes in a yearlong running battle across the plains in the Red River Wars. After their surrender, the military charged 72 Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche, and Caddo warriors with war crimes or with being “ringleaders.” Sheridan ordered them sent “to an eastern fort to be held without trial for an undefined time.”

Lt. Richard Henry Pratt accompanied the prisoners on their journey to the Spanish colonial town of St. Augustine. There, the homesick warriors became a boon to the tourist industry, created art, went to school, met leading lights of the Gilded Age, learned to sail, attended church, and acquired the nickname “Florida boys.”

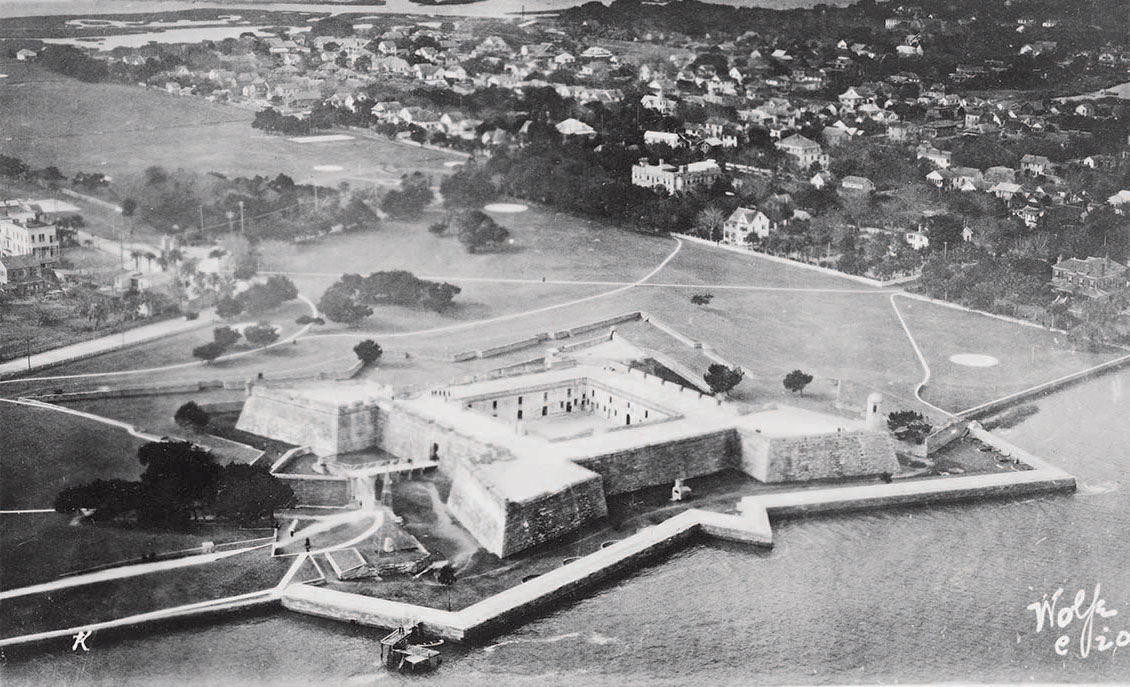

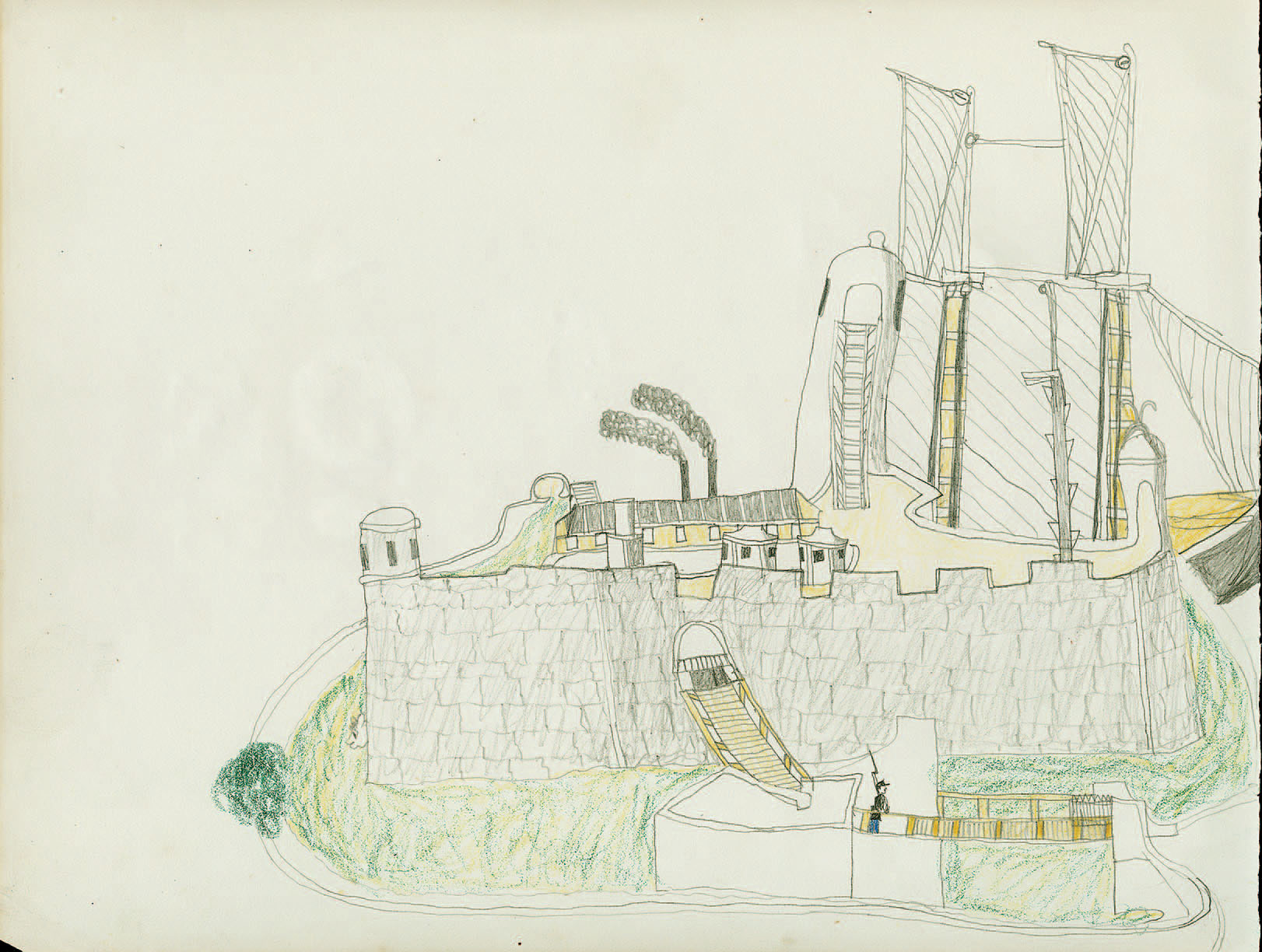

The townspeople accepted the prisoners, and “they were allowed to go about our city without anyone to look after them,” recalled Julia Gibbs in a memoir she wrote for her family. Fort Marion, their prison and home for the next three years, was in poor condition. The Spanish had begun the coquina fort in 1672; renamed Fort Marion by the U.S. Army, it would eventually become a National Monument called Castillo de San Marcos. The fort’s arrow-shaped parquet corners jut out to four compass points. A contemporary Cheyenne peace chief described his epiphany when he noticed how the compass directions resembled the four sacred arrows given to the Cheyenne by their prophet Sweet Medicine. Bowstring officer, Cheyenne warrior, and future Episcopal saint Making Medicine (Okuh-ha-tuh) wrote he “was astonished when I saw old Fort.”

Pratt removed the prisoners’ shackles and had a wooden barracks erected on the northern upper parapet to house the single men. The two married couples had separate quarters. Illness, homesickness, and depression combined with Florida’s summer heat and the fort’s lack of proper facilities increased mortality. Pratt bargained his career and formed a company of prisoners as sergeants and corporals to act as guards, issued uniforms, and gave permission for the prisoners to attend any of the churches in town. Bishop Henry Whipple, called the “Apostle to the Indians,” was in St. Augustine for his wife’s health. A former rector of Trinity Episcopal Church, he became a regular visitor at the fort, and the church’s burial records show funeral services were held for Big Moccasin, Lean Bear, and Spotted Elk.

Contemporary Native Americans often view the Fort Marion imprisonment as a concentration camp experience. The prisoners, too, wondered why they were there. Some supporters and benefactors tried to mitigate the negative circumstances. Pratt endeavored to build hope among his charges and continuously sought their release. Soon after arriving at Fort Marion, he appointed Making Medicine as first sergeant with full authority in his absence.

One contemporary said Making Medicine had a “presence that would bring him notice in any society.” A spiritual seeker, he had a conversion experience and attended Trinity Church on Sundays. He met a kindred soul in Alice Key Pendleton, daughter of Francis Scott Key. She, her husband, and their daughters became friends with Making Medicine and later supported his seminar studies. (Alice also arranged for an eye operation for Howling Wolf in Boston.) By the time of her death in May 1886 in a Central Park carriage accident Pendleton had seen her protégé become an ordained deacon in the Episcopal Church and take as his name David Pendleton.

Longings for home and families united the prisoners, and in June 1875, Kiowa medicine man Mah-Mante (Skywalker) was selected to send a message to Washington. “I am speaking now for the Kiowas and Comanches here; and as sure as God (the sun) hears me speak, I am telling you what our hearts all say, only give us our women and children.” President Grant agreed but later changed his mind, which may have led the Kiowas in the spring of 1876 to plot an escape, which Pratt foiled.

The young men selected Making Medicine to speak for them in an 1877 letter. “We have lived in this old place two years,” he wrote. “It is old and we are young. We want Washington to give us our wives and children, our fathers and mothers. We are willing to learn and want to work.” The first sergeant kept the roll call roster in English by then. Tourists and residents of the town helped the prisoners learn English, but the education really began when Mount Holyoke graduate, educator, and abolitionist Sarah Mather viewed their condition and told Pratt she would set up a classroom. Mather had a “born genius for instruction” according to her friend Harriet Beecher Stowe. Mather asked sisters-in-law Julia Gibbs, widow of Confederate Col. George Couper Gibbs, and Laura, widow of Kingsley Gibbs, to join her.

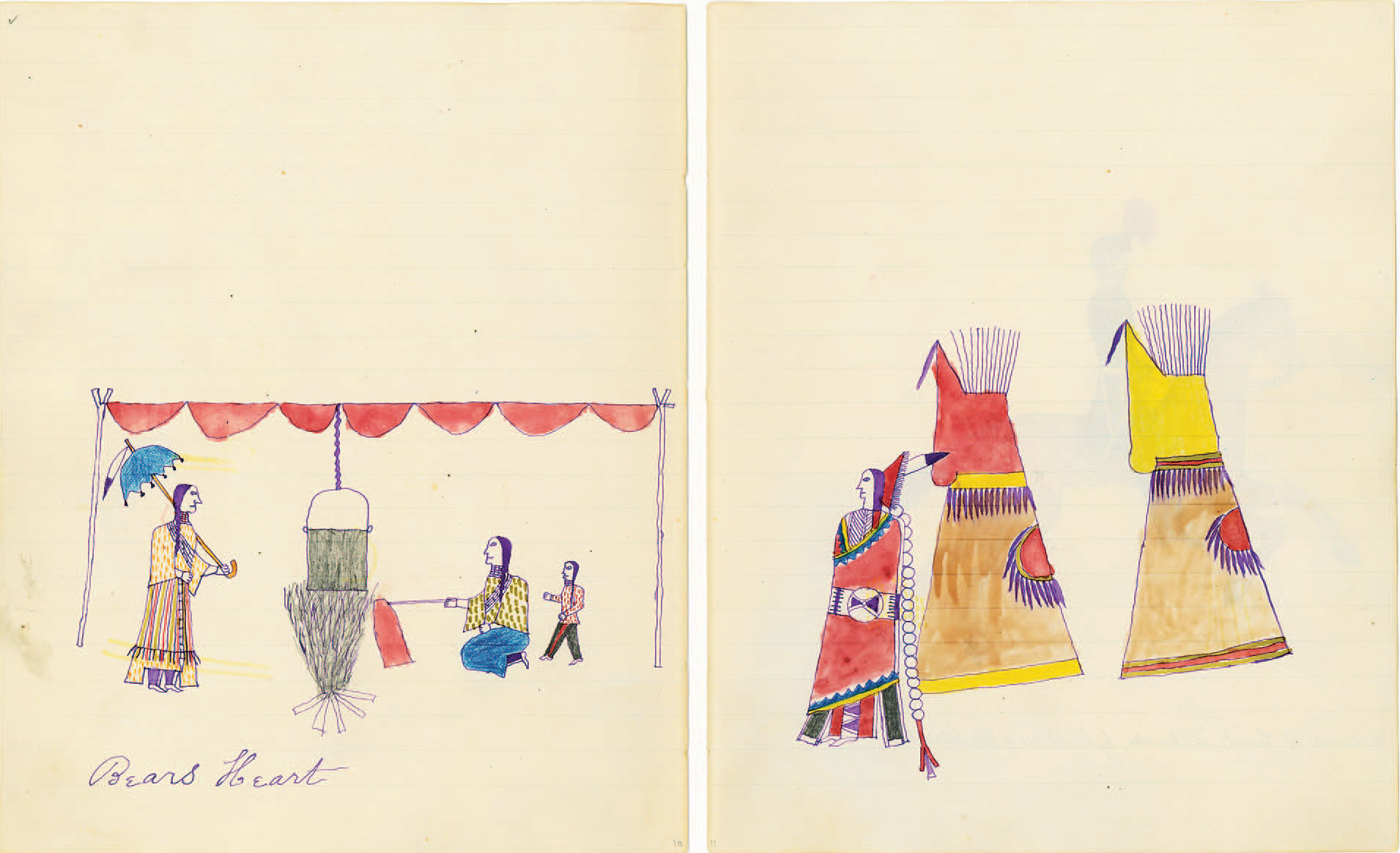

Julia also taught the prisoners carpentry. Bear Mountain wrote: “One teach work, work with hands — that is little Miss Gibbs — her sister big Mrs. Gibbs — so good — tell all the time about God, soul, and God.” He worried that the women received no pay. “Perhaps God will pay you all.” Ledger artists depicted the two women wearing Victorian widow’s clothing, one short and plump, the other tall and thin. Friendships developed between students and teachers, and the women became ardent letter writers on the prisoners’ behalf.

“They were prisoners of war except one woman and her little girl, about nine years old. She was the wife of Black Horse. ... There was one prisoner woman [Mochi] who had killed a Germain with an ax,” Julia Gibbs remembered. She described Dick, Kiowa Chief Lone Wolf’s former African American prisoner, and a person no other history has mentioned: “There was an Irishman stolen when a baby — known as Irish, full of fun at all times.”

Mochi, a Cheyenne warrior who witnessed the Washita Massacre, had fought alongside her husband, Chief Medicine Water. At Fort Marion, she spent hours staring out at the sea and never wavered in her refusal “to take the white man’s road.” Women of the town had her and Black Horse’s wife and daughter, Pe-ah-in and Ahkah, in Victorian dresses.

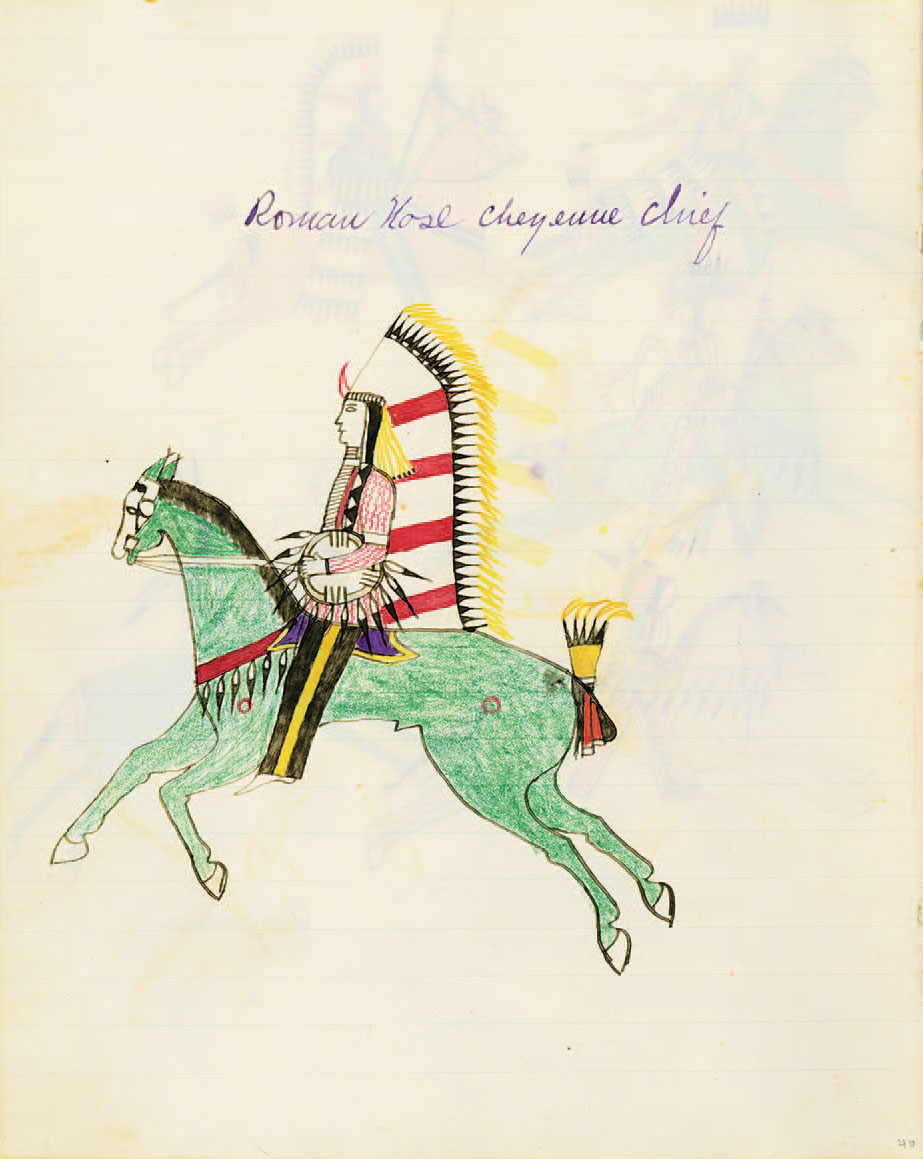

Roman Nose thought people came to St. Augustine because of the “fine weather,” and praised the “local hospitality and good friends.” Making Medicine also remarked on the weather: “Nice weather. Warm and pleasant.”

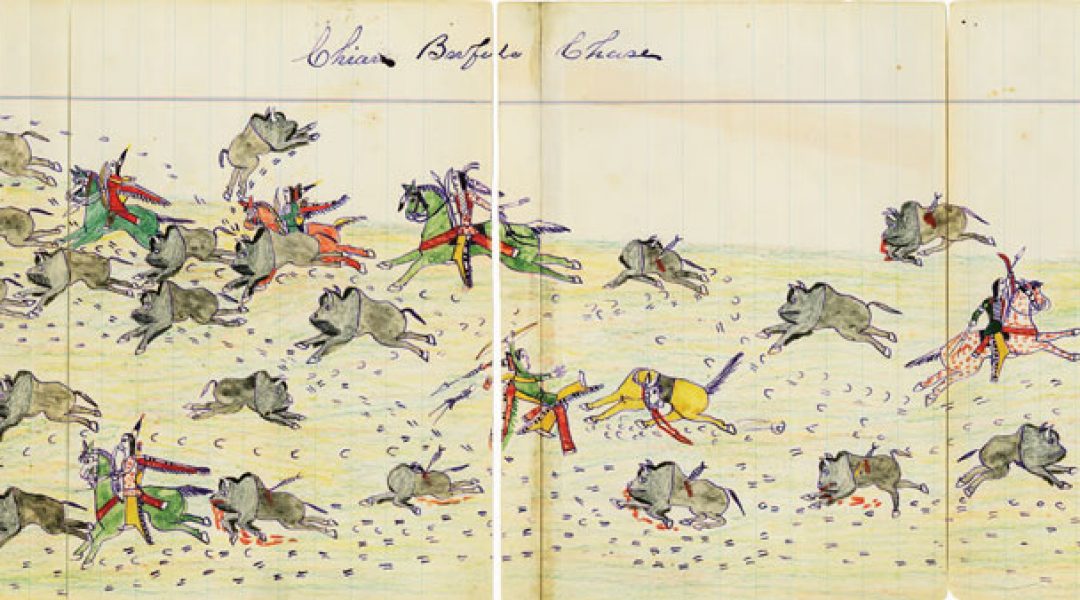

A picture letter arrived from Oklahoma to Cheyenne prisoners, and Pratt noticed morale increased. He purchased art supplies and distributed them, choosing Zotom, a warrior who had fought with Mah-Mante, along with Making Medicine, to be the first to receive art materials. Soon, ledger art books became the most popular tourist purchase.

Smithsonian historian and curator Herman J. Viola says the Fort Marion ledger artists showed the world that “Indian peoples of the Americas possess an inherent sense of beauty and harmony, and artistic strength that transcended racism, adversity, and all the other efforts that conspired to eradicate their inner soul.”

The presence of the warriors attracted thousands of visitors to St. Augustine. Besides the tourist trade, warriors worked on construction projects, in hotels and on the railroad, and took tourists sailing on two yawls Pratt had purchased. They earned thousands of dollars and sent money home to their families. They also became favorite customers at local shops. The yacht club often invited the affable 60-year-old Chief Eagle’s Head (Minimic) sailing, and he purchased and wore correct man-of-leisure attire on those occasions. Minimic sent his family word: “I have had a good time since I came here.”

The Holiday Regatta of Lights at St. Augustine that still delights visitors and residents in the winter season began with the “Indian Sports and War Dance” arranged by Pratt and Robert Bronson of the Yacht Club. Social life was limited in the small town and a New York Observer reporter said, “multitudes of ladies ... while away their idle hours at the fort and throw themselves upon the red men in a way that is perhaps overdone.”

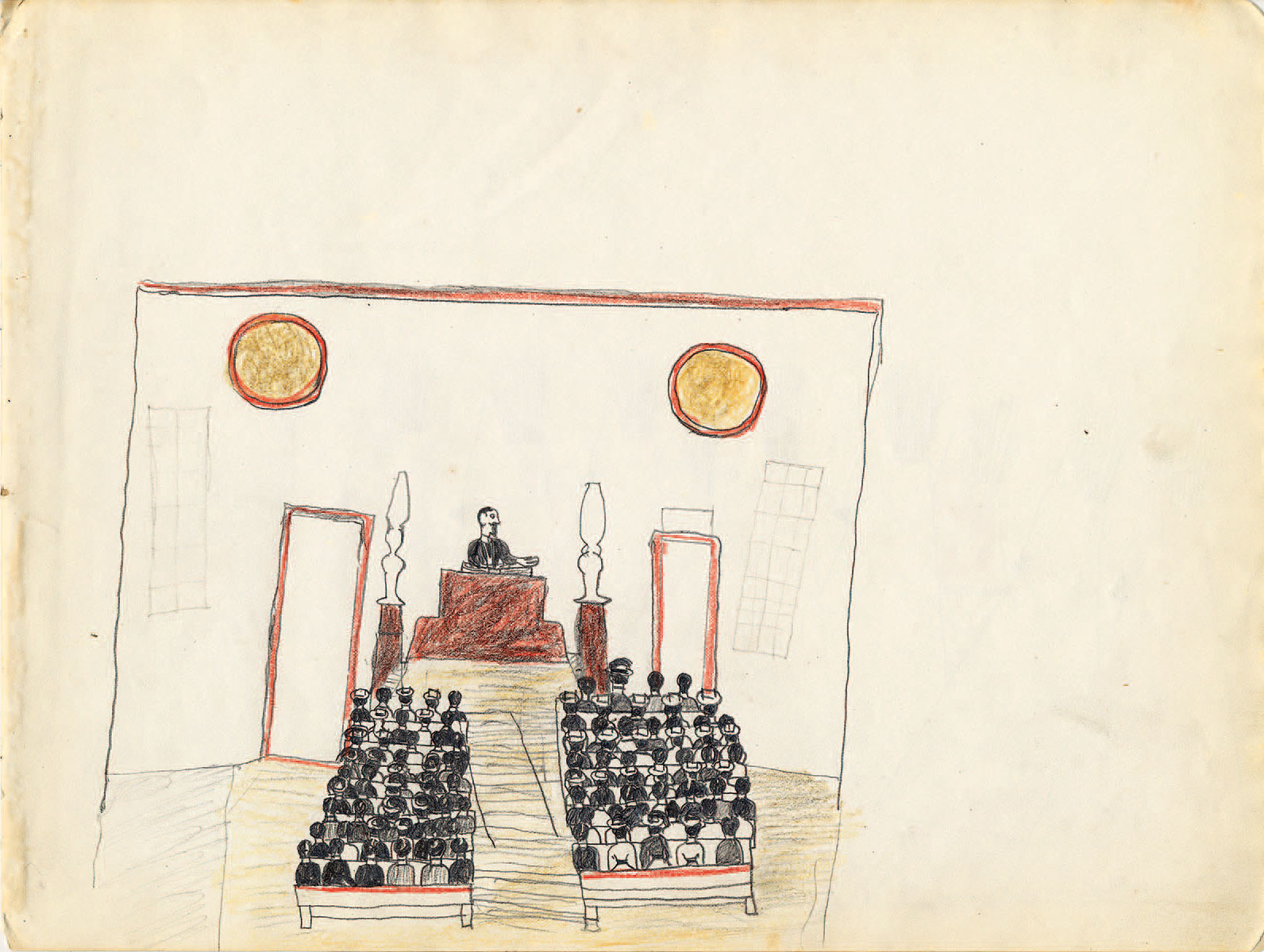

Tourists and residents liked joining the prisoners in their Monday evening services and singing.

One favorite was the rousing hymn inspired by a Civil War message from Sherman, “Hold the Fort, for I Am Coming,” recalled Mary Carruthers, a volunteer teacher and regular winter visitor. One line, “Fierce and long the battle rages,” may have had a different meaning for the Southern Plains warriors.

Lt. Col. Frederick Dent, the Army post commander and President Grant’s brother-in-law, joined Pratt in requests for the prisoners’ release. Finally, newspapers described the scene in April 1878, as tearful townspeople waved goodbye to the “Florida boys.” Together, the former prisoners and townspeople sang “The Sweet By-and-By.”

Fort Marion Ledger Artists: Epilogue

They drew their art on fragile paper, yet more than a thousand examples of Fort Marion prisoner-artists’ work can still be found in collections around the world. Here’s a brief look at the lives of some of the imprisoned warriors after their release.

Making Medicine

Known for his sophisticated compositions, Cheyenne spiritual leader Making Medicine (David Pendleton Oakerhater) attended seminary after his release. An Episcopal deacon, he served his people for 50 years and was called “God’s Warrior.” The Episcopal Church named him a saint in 1985. Every September, the Oakerhater Episcopal Center in Watonga, Oklahoma, holds an Honor Dance in his memory.

Howling Wolf

Howling Wolf returned to a Cheyenne lifestyle after his father, Minimic, died, but he created one ledger art book in watercolor and ink. Late in life he earned money performing in Indian dances. Driving home from a performance, his car was hit; he died July 5, 1927 from his injuries.

Zotom

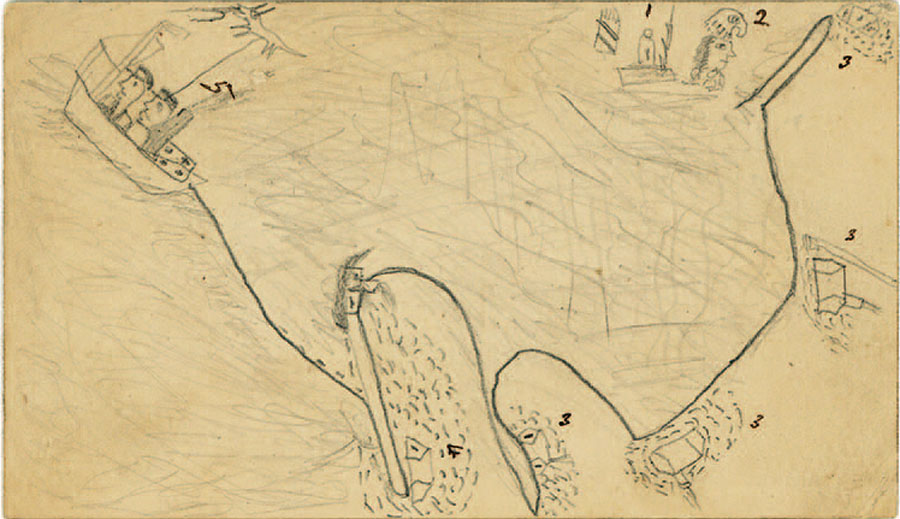

Kiowa artist Zotom (Biter) drew landscapes of his journey from Indian Territory to Fort Marion. He, too, attended seminary, and he adopted the name Paul Caryl. He later joined the Native American Church. The model tepees he created for the Omaha Exposition of 1898 are his only known artwork after leaving Fort Marion.

Bear’s Heart

Bear’s Heart (Nockkoist) attended the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, a historically black college founded in Hampton, Virginia after the Civil War, which created a program in 1878 to teach American Indians. Ill from tuberculosis, he returned home and worked as a carpenter. He died in January 1882, and was buried beside Chief Minimic. Bear’s Heart’s ledger book given by Bishop Whipple to Gen. Sherman is in the National Museum of the American Indian.

Etahdleuh Doanmoe

Etahdleuh Doanmoe attended the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and Hampton and married before returning to the Kiowa reservation as a Presbyterian missionary. He died suddenly in 1888 at the age of 32. Pratt kept drawings by Etahdleuh, which his son Mason compiled and added typed descriptions to.

From the August/September 2017 issue.