From the 1539 Hernando de Soto expedition to the Battle of Bear Valley in 1918, the visually impressive and densely informative “The Indian Wars” takes the reader through the stories of resistance, the stories of conflicts between empires and within tribes, and the stories of conquest and survival.

During the War of 1812, Shawnee chief Tecumseh outsmarted American Brig. Gen. William Hull, tricking him into surrendering Fort Detroit without a fight.

Tecumseh was a revered unifier of Native tribes and a survivor of multiple wartime atrocities. His father was killed in the Battle of Point Pleasant in 1774, and the villages where he lived as a child were torched by a militia. But one of Tecumseh’s greatest triumphs was a nonviolent one. At the Siege of Detroit, he marched 400 of his warriors past the fort, and then instructed them to stand behind British forces on a hill — or so it appeared. In truth, his Native warriors circled back through the woods and marched past the fort again. Tecumseh repeated this tactic over and over, creating the optical illusion that his force was massive.

The chief is said to have approached Hull and stated, “Only fools fight a battle where they’ve already lost. We are people of honor. Surrender the fort, your cannons, and all your weapons. We’ll hold the soldiers prisoner and let all the civilians go. Nobody’s going to die today.”

Hull abided by the suggestion and Tecumseh claimed 2,500 captives, at least that many muskets, and 33 cannons. British Maj. Gen. Isaac Brock was so blown away by the accomplishment that he convinced the British government to offer a brigadier general appointment to Tecumseh. The brash and loyal Tecumseh refused.

This story is just one of dozens told in The Indian Wars: Battles, Bloodshed, and the Fight for Freedom on the American Frontier (National Geographic, 2017). Opening in 1539 with the Hernando de Soto expedition, the narrative takes the reader through wars of resistance, wars between empires and within tribes, and wars of conquest and survival, ending with the Battle of Bear Valley in 1918.

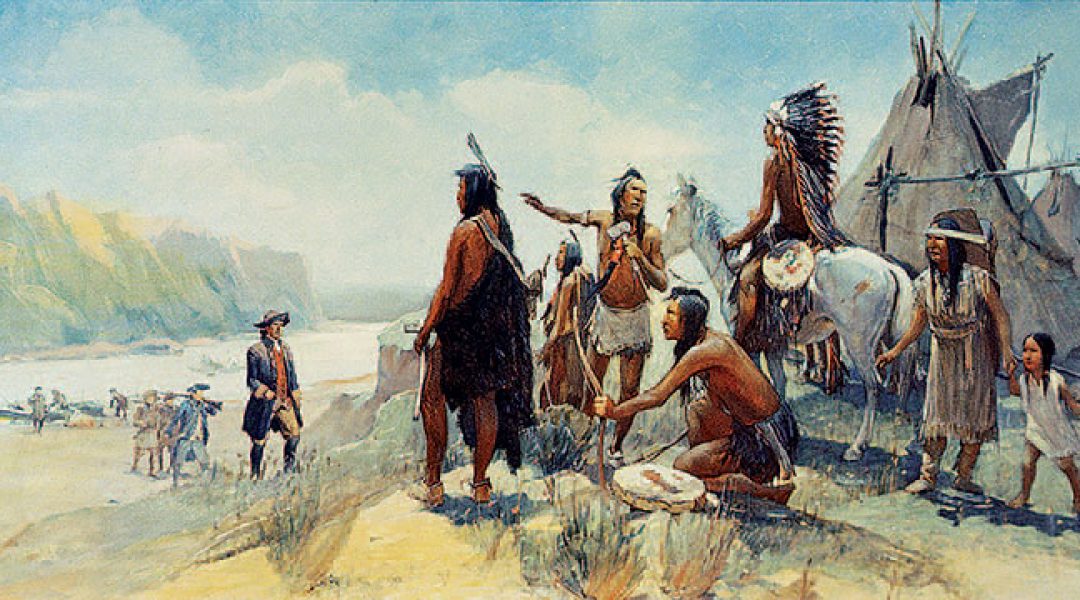

The book is as visually impressive as it is dense with information. Historical photographs, artwork, maps, and timelines help the reader envision what life — and war — was like during these conflicts that seem so long ago.

“It can be a disheartening subject matter,” author Anton Treuer says. “I think a lot of people realize there was a contest over land and resources and it got bloody and it was nasty and it wasn’t always fair and there were some unscrupulous dealings.”

There had been fighting among tribes before European contact, but it was a different kind of conflict. Tribes were territorial and battled over cultural imperatives, but they weren’t trying to commit genocide, convert one another, or alter the culture of their enemies.

That changed with the arrival of European settlers and the inevitable clash of cultures. Whether Natives looked at newcomers with awe, hopes for friendship, or offense, they still saw them as human beings. Europeans rarely reciprocated that sentiment. In response to the antagonism, tribes developed different strategies to deal with the rising tensions. One strategy was to fight. Another was to accommodate. A third was a hybrid approach combining tougher diplomacy and the threat of force.

In combat, Native tribes weren’t simply mowed down. They had their own fighting style, including guerrilla warfare and tactics like double envelopment. They often stumped Europeans and Americans, just like Tecumseh did in 1812.

“We see not just horrible violence,” Treuer says of the book’s narrative arc. “We see the humanity — and inhumanity — of the players on both sides. We see tactics and strategies and outcomes that completely transform everyone. The way the world wages war is different now. It’s not just about who killed who when.”

One of the challenges Treuer faced was boiling down hundreds of years of military history in a way that engaged readers but wasn’t mind-numbingly violent. Treuer is aware of the sugarcoated version of Christopher Columbus and the first Thanksgiving that many Americans have been fed. Contrary to the kind of historical writing that can be dull or dry, Treuer has built a career on making Native history compelling and relevant to contemporary readers of all ages and educational levels.

“History’s only boring if you get history the way they do it in high school. History is not dates and events. History is stories. And, ultimately, of interest to people are the stories of how they got here and became who they are,” Treuer says.

His tone in The Indian Wars is less scholarly and more like that of a tour guide: accessible, easygoing. Treuer is an expert storyteller, and the tales he shares are those of clever warriors and unlikely victories. “There are so many geniuses on both sides, so many horrible things, sometimes beautiful things. The relationships are very complicated.”

The Indian Wars also offers readers a more balanced telling of the bloodshed. Treuer, a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, can take credit for that. He didn’t rely solely on archival history sources such as an army officer’s or chaplain’s journal. Instead, he tapped into Native voices and views to explore how these historical events impacted both sides.

Given that history buffs gravitate toward this genre of book, Treuer was meticulous about ensuring the accuracy of the tales. “Sometimes you do have to chase something way deep into the weeds to make sure it’s right. I’ve been lucky to have been well-traveled throughout Indian country. I have a lot of relationships and I can call somebody up, even in places that are fairly closed, like the pueblos,” he says.

While The Indian Wars takes place in the past, the repercussions of those times endure today. “It isn’t just who owns the land and who gets to benefit from the resources, but the way we wage war and structured our political system has been deeply formed by all of that,” Treuer says.

Whites and Natives no longer battle at the magnitude described in The Indian Wars, but subtler forms of conflict persist in American culture where deeply scripted and held beliefs about individualism, materialism, and competition rule. “There are a lot of ways to wage war,” Treuer says. “There are a lot of ways to conquer somebody. A gun is only one way.”

To read more about Anton Treur, read "Modern Native Voices" by Chuck Thompson.

From the January 2018 issue.