Writing on and off the reservation, in genres ranging from poetry to memoir to apocalyptic science fiction, these writers are reshaping the meaning of “Native American literature.”

Indian reservations, and those of us who live on them, are as American as apple pie, baseball, and muscle cars,” writes David Treuer, a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, in his 2012 tour de force Rez Life. Though not all of them focus on the reservation experience, a wave of contemporary writers share Treuer’s red-white-and-blue sentiment. With humor, history, and even sci-fi, they are reshaping the idea of what it means to be a “Native American writer.”

Some of the most familiar names in the Native American canon — James Welch, Joy Harjo, Simon Jo Ortiz, Leslie Marmon Silko, N. Scott Momaday, Louise Erdrich — gained prominence as part of the Native American Renaissance that kicked off in the 1960s. In the words of a 1997 New York Times story about contemporary Native writers, these masters are “writers of lyrical prose whose work is mostly set on reservations and suffused with longing for the vanished coherence of the tribal world.”

These days, the literature of indigenous peoples is more often led by self-described “urban Indians,” university professors, and iconoclasts such as Sherman Alexie, whose 1995 debut novel, Reservation Blues, heralded a sea change in Native American literature.

“Today’s landscape is fertile and vibrant,” says Anton Treuer (David’s brother and pictured above), mentioning the 1491s, a Native American sketch comedy group; Ponca/Ojibwe screenwriter Migizi Pensoneau; and Ned Blackhawk, a Western Shoshone professor of history and American studies at Yale. “There is a growing cadre of Native writers who are emerging to make that landscape more productive than it’s ever been.”

Selected from a wide group — with regrettable omissions that could fill a book of their own — these Native American writers have us turning pages.

Anton Treuer

Scroll through online reader comments on Anton Treuer’s history, linguistics, and social commentary and you’ll find comments like “Bridging the divide” and “Every American should read this book.” That’s validation for Treuer, a professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University in Bemidji, Minnesota. He’s the author of 14 books whose goal is to shine a light on misconceptions about Native Americans using gentle rhetoric that avoids recrimination and vitriol.

“I’m not trying to win a popularity contest so much as provide people with approachable information and knowledge,” Treuer says. “I try to connect with people and provide tools to help transform our society.”

Taking on everything from “the real story of Thanksgiving” to the intricacies of tribal politics, his short and highly readable Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians but Were Afraid to Ask is always measured, and occasionally funny. Why are they called “traditional Indian fry bread tacos”? This is one question Treuer admits he has no clue about. “Frankly, the words traditional, Indian, fry bread, and taco do not have any business even being in the same sentence,” he writes.

“The only things most schools teach about Native Americans happened before 1900 and it’s a story with a tragic ending,” Treuer says. “Indians are too often something that happened in the past, not something that’s happening right now.” Treuer is helping change that perception.

His latest book, The Indian Wars: Battles, Bloodshed, and the Fight for Freedom on the American Frontier was published in hardcover by National Geographic in October 2017.

Sherman Alexie

Because he really belongs in a category of his own, it’s tempting to leave Sherman Alexie off a list of essential Native American writers. But his 2017 memoir, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, is a gripping achievement that belongs in any discussion of his best work. Once again, the bombastic Alexie makes himself impossible to ignore.

From the beginning of the new book you’re drawn in by Alexie’s irreverent rez wit and twisted bon mots: “I don’t believe in ghosts. But I see them all the time.” “In my rural conservative Christian public high school ... I was the only Indian except for the mascot.” “Poverty was our spirit animal.”

Broadly a remembrance of his hate-love relationship with his deceased mother, the book is as much an elegy to the family and community dysfunction that’s followed him throughout his life and infused his writing. Now living in Seattle, Alexie grew up on the Spokane Indian Reservation in rural Washington. Murder, sexual assault, incarceration, disease, dishonesty, and other disturbing episodes pepper the book. “Singing and screaming and cursing and pistols and rifles fired into the night sky,” he writes. “Those reservation Indian parties felt less like celebrations and more like ceremonial preparations for a battle that never quite arrived.”

Despite the mayhem, Alexie maintains a breezy voice that makes it all seem ... if not fun, at least funny. Perhaps the only other American author who’s ever dealt with unspeakable family tragedy in such bizarrely entertaining fashion is John Irving. The comparison between the ills of New England society and those on a Western reservation isn’t far-fetched — it’s affirmation of Alexie’s rank as a preeminent American storyteller of his time.

His standing as the mark to which other Native American authors aspire remains unmatched. As Daniel H. Wilson, another writer on this list, told us: “I was recently invited to contribute to an anthology that Sherman Alexie is also contributing to. Man, that’s cool! I’m really excited about that.”

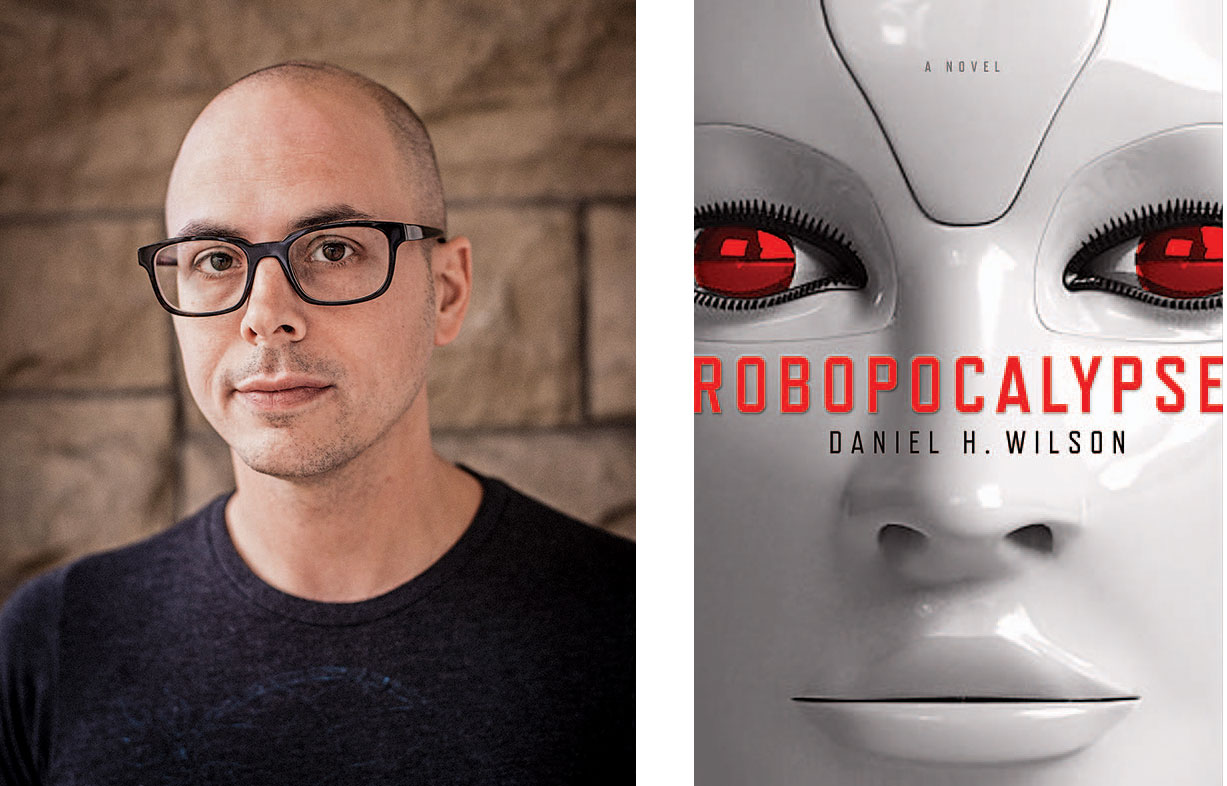

Daniel H. Wilson

If Daniel H. Wilson were the publisher of this magazine, he might rename it Cowboys Are Indians. Or Indians Are Cowboys.

“Where I grew up, Native Americans and cowboys had a lot in common,” says the Cherokee Nation member, who grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “Both are often depicted as stereotypes, but in the real world I don’t think they’re mutually exclusive. When a screenwriter asks me how to deal with Indian characters, I tell them to just treat them like regular people and you’ll be fine.”

The strongest example is Lonnie Wayne Blanton, a tough Osage Nation elder who functions as a moral pivot in Wilson’s 2011 bestseller Robopocalypse, a near-future fantasy about renegade robots forming an army to destroy the human species.

The Osage Nation and its spiritual home in Gray Horse, Oklahoma, wind up becoming the bastion of the human resistance, with Blanton as its figurehead. The tribal leader rouses his army with a traditional Osage war dance, but as the wild story bounces around the planet, he figuratively transforms into something else. Eventually, he strides into a scene “[j]ust like a damn cowboy.” Blanton shouts, “Howdy, y’all!” to his multiethnic tribe and wields a Zippo lighter emblazoned with Roy Rogers’ initials and the inscription “King of the Cowboys.”

By the novel’s 2014 sequel, Robogenesis, Blanton is introduced as “an old cowboy who happens to be our general.”

“Blanton is based 100 percent on my grandfather, who is one of the toughest people I know, and I always thought of [my grandfather] as a cowboy,” Wilson says.

With a PhD in robotics from Carnegie Mellon University, Wilson burst onto the sci-fi scene in 2005 with the humorous (or was it?) guide How to Survive a Robot Uprising. He’s carved a niche with such books as How to Build a Robot Army and the 2017 novel The Clockwork Dynasty (20th Century Fox Studios has already bought the rights), a gonzo global odyssey that tracks the fate of ancient humanoid robots who walk among us today.

Although Native American themes provide an emblematic subtext, Wilson is most interested in the way humanity as a whole interacts with technology. To some, that may make him a unicorn among Native American authors. To Wilson, the fuzzy lines are normal.

“I never set out to be acknowledged as a Native author,” he says. “It’s just the world I grew up in. When you’re raised in Oklahoma, it can seem like everyone is Native American. You don’t even think about it. It’s not a big deal.”

Debra Magpie Earling

Some writers change the landscape with their writing. Others do it through teaching. Debra Magpie Earling, a Bitterroot Salish tribal member, does both.

The story behind Earling’s 2002 debut novel Perma Red is almost as epic as the book’s success. Endlessly rewritten over nearly two decades, one manuscript was lost in a fire, and countless publishers rejected it. That was small beans compared to the tragedies at the heart of the story of a teenage girl on the Flathead Indian Reservation caught in a ferocious love quadrangle.

“Though Perma Red is based on my Aunt Louise’s difficulties, the truth of the story is based on my own life experiences with murder, suicide, and abuse,” Earling says.

The book won the Western Writers Association Spur Award, a WILLA Literary Award from Women Writing the West, and an American Book Award. Earling went on to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship and in 2016 became the first Native American to be named director of the University of Montana’s creative writing program.

“Younger Native writers have a tougher road,” Earling says. “We see enormously talented writers each generation, but it seems only two or three become lauded by the larger publishing houses. I’m hoping that will change. ... I am so proud that the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe is generating a whole new wave of Native writers.”

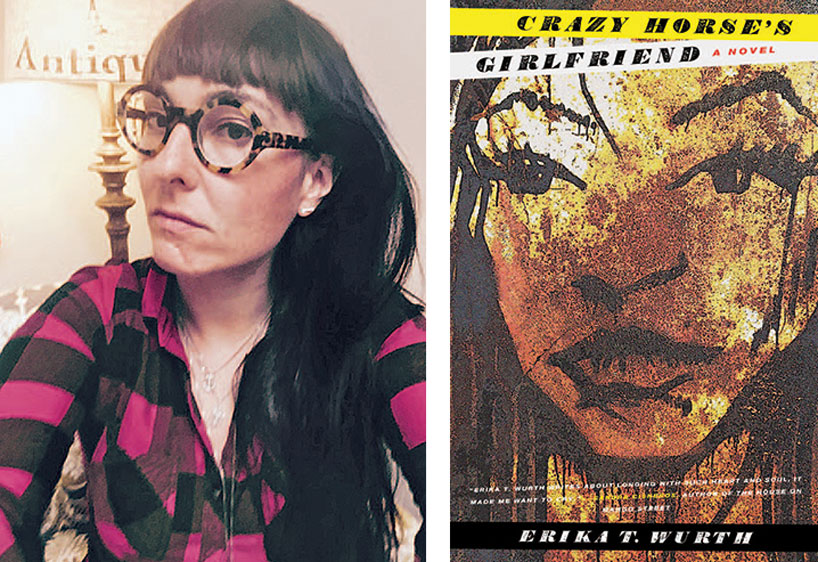

Erika T. Wurth

There’s a lot of Holden Caulfield in the teenage narrator of Erika T. Wurth’s Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend — if Holden were a “sharp-tongued drug dealer,” as Wurth describes her.

Profanity and gruesome situations will put off many readers (consider that fair warning), but the gritty 2014 novel about a drug-dealing and pregnant Native American teen who dreams of a life beyond the futureless existence she feels trapped inside drew the acclaim of many. Booklist called it an “affecting look at the ineluctable awfulness of some teens’ lives.”

Raised outside of Denver and now a creative writing professor at Western Illinois University, Wurth (Apache/Chickasaw/Cherokee) set her 2017 short story collection Buckskin Cocaine within a troubling underworld of the Native American film industry and “men maddened by fame, actors desperate for their next buckskin gig, directors grown cynical and cruel, and dancers who leave everything behind in order to make it, only to realize at 30 that there is nothing left.”

“Erika Wurth is a writer to watch,” Debra Magpie Earling says. “Her writing glints on the dark edge of Indian urban experience. Her characters don’t have happy endings. She writes unflinchingly with brute force and intelligence.”

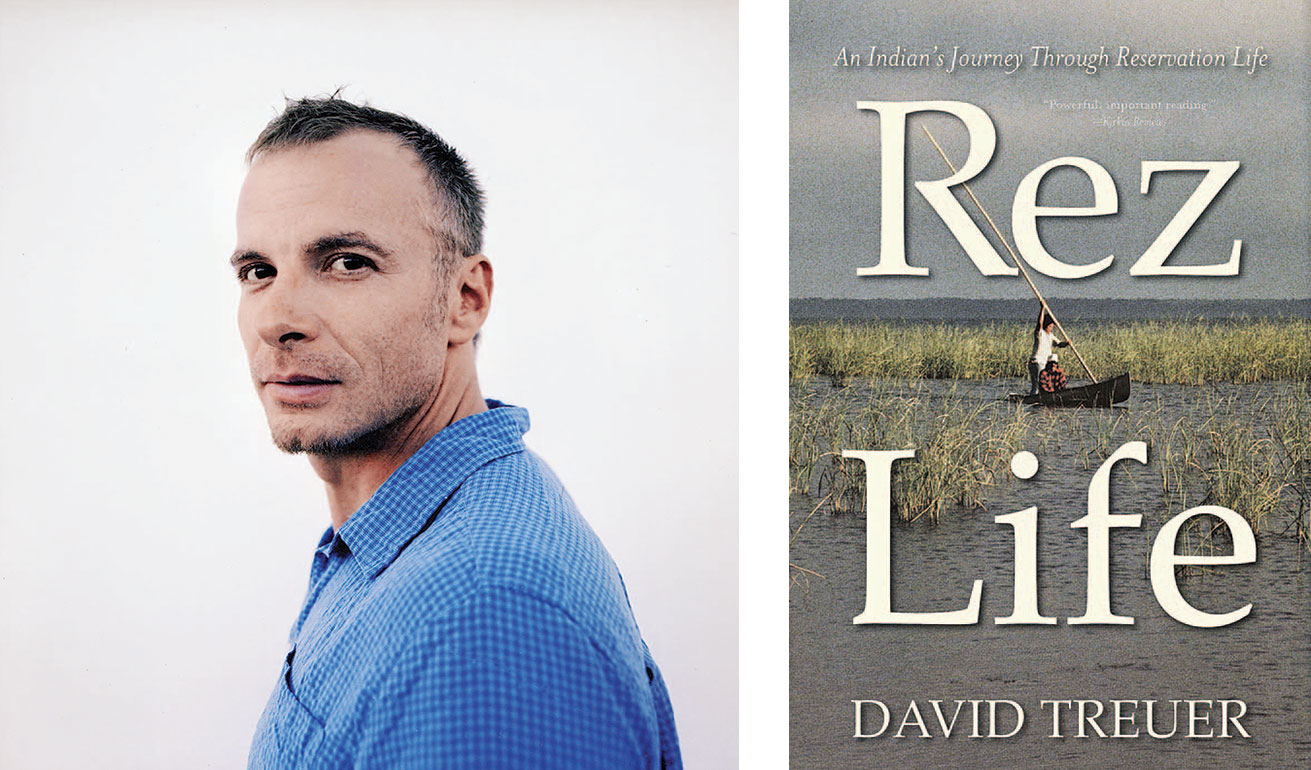

David Treuer

In a short list of important Native American writers, it seems unfair to reserve places for two brothers. But Anton’s younger sibling has a sterling writing résumé of his own, and his exacting research and didactic style set him apart from more colloquial authors.

Treuer’s 2012 opus Rez Life, which he calls a blend of “journalism, history, and memoir,” opens with a flurry of statistics and facts — there are roughly 310 Indian reservations in the United States and 564 federally recognized tribes — that signal a writer deeply committed to detail. Yet he’s capable of dealing with the bleeding heart of his reservation muse: “What are these places that kill us every day but that we’d die to protect and are like no place else on earth?”

The author of four novels, Treuer has also not shied from controversial opinions. In 2006’s Native American Fiction: A User’s Manual, an extended essay places Sherman Alexie’s acclaimed novel Reservation Blues in the same class as the infamous 1976 fraud The Education of Little Tree. That book’s supposed Cherokee author was unmasked as a former Ku Klux Klan member named Asa Earl Carter not long after its initial publication. Only after its reissue hit bestseller lists and its well-worn clichés earned widespread critical acclaim did the hoax become widely known.

“Little Tree,” Treuer wrote in an essay that questions focusing on authors’ authentic ethnicity rather than their texts’ literary merits, should be considered “as ‘Indian’ as Reservation Blues.” For good (or bad) measure, Treuer blasted Alexie’s “freshman attempts at humor and poetry” and lumped another Native literary hoax — Tim Barrus, an Anglo writer who adopted the Native moniker Nasdijj to pass off a successful series of putative Indian memoirs — into the same class as Alexie.

Though he doesn’t name names, one easily imagines Treuer as a target of a scathing chapter titled “Dear Native Critics, Dear Native Detractors” in Alexie’s 2017 book, You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me. Or in his short poem titled “The No,” which reads: “So we must forgive all those/Who trespass against us?/F--- that s---./I’m not some charitable trust./There are people I will hate/Even after I’m ashes and dust.”

Unsettling as this all may be, there’s nothing like a good, long-running literary feud to serve as evidence of a vibrant writing culture — this stuff matters — and Treuer is in the thick of it.

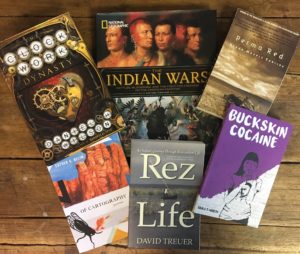

25th Anniversary Giveaway

25th Anniversary Giveaway

There will be fun giveaways with each issue in 2018, to celebrate the magazine's 25th anniversary year. Want to win a selection of great books from several of the featured authors above? Follow C&I on Instagram and leave a comment on this post for a chance to win. We'll notify the winner via Instagram,

Read more about The Indian Wars: Battles, Bloodshed, and the Fight for Freedom on the American Frontier by Anton Treur (National Geographic, 2017).

From the January 2018 issue.